The year is 1980 and the U.S. post-deregulation airline industry is still taking shape. While the established carriers are making adjustments in the new competitive climate, you and your management team are about to launch a radically different airline company. You only have three airplanes, but you have assembled a vast pool of human potential, motivated by a compelling vision of creating a “better world.” You have mapped out your strategy: expand aggressively by marketing heavily, offer unheard-of low fares, and provide superior service. You believe that you have assembled everything needed to make this new airline fly — you wonder how high People Express will soar…

Daring Experiment

People Express Airlines was a daring experiment, going from startup to over $1 billion in revenues in less than four years — the fastest growing company in the history of America at that time. It offered deep discount fares, innovative human resource policies such as employee ownership, self-supervised teams and job rotation, and a charismatic founder, Don Burr. But the interaction of these strengths produced a disaster. In the first six months of 1986 the company lost $132 million, and in September of that year it was swallowed up by Texas Air.

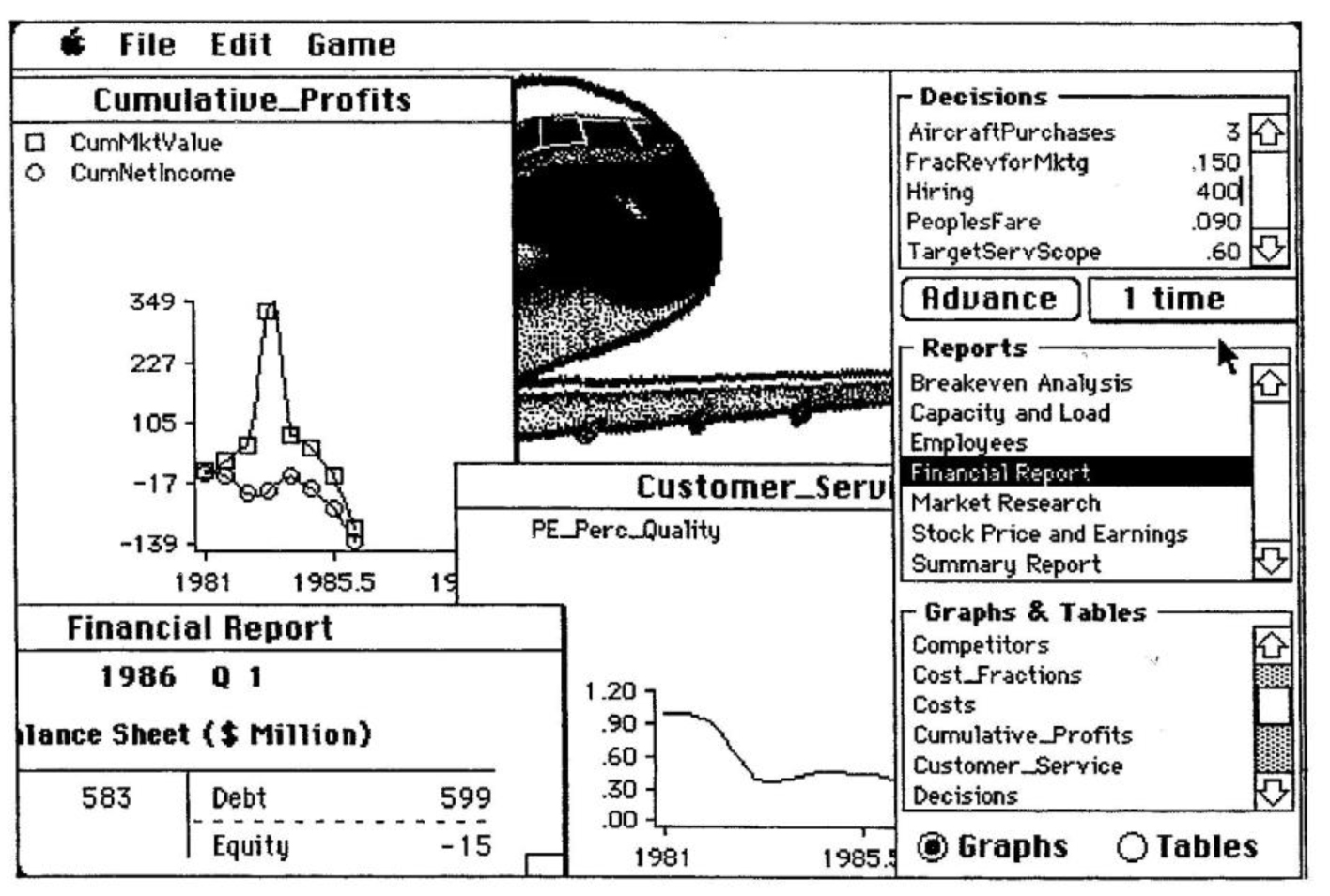

Although People Express no longer exists, it is possible to reenact the scenario described above by climbing into the cockpit of a new tool called a management flight simulator. A management flight simulator, similar to the ones used to train pilots, allows managers to test the outcome of different policies and decisions without “crashing and burning” real companies. It is made up of a system dynamics model that has been changed into an interactive game by the use of an interface (for more information on software for creating interfaces, see this issue’s Viewpoint).

The People Express Management Flight Simulator was the first of its kind. The simulator was developed by Professor John Sterman at the MIT Sloan School of Management using STELLA. Ernst Diehl, president of MicroWorlds, Inc., developed the interface software. Introduced in 1988 as part of an orientation workshop for incoming Sloan School master’s students, the simulator has since been adopted by dozens of universities, including Harvard Business School, Stanford Law School, London Business School, and the University of Texas. It has also seen wide use in management training at all levels of management in dozens of major corporations.

‘Tangled Webs’

According to Sterman, the system dynamics model behind the People Express Simulator integrates the structure of People Express — its operations, human resources, organizational structure, and philosophy — with the structure of the US air travel market and competitive environment of the early 1980s. In addition to “hard” variables such as fleet size and financial data, the model includes such “soft” variables as the effects of overtime on morale, and the effects of service quality on the airline’s reputation.

The People Express Simulator workshop puts each participant in the role of the top management, where they must “wrestle with the tangled web of cause-and-effect relationships that create corporate dynamics,” as Sterman describes it. But in addition to real-time problem solving, the workshop offers participants the chance for reflection and inquiry, an opportunity that is seldom afforded to managers during their hectic daily schedules.

Although various instructors have developed different ways to use the simulation, Sterman says he begins his workshop with a short review of People Express’ history and a screening of a 1985 video clip in which Don Bun speaks about his philosophy and vision for the company. The video invariably stimulates vigorous discussion, says Sterman, in which participants offer their own theories of why the company failed and suggest alternative strategies.

In the Pilot’s Seat

Then comes the real test of those theories. Participants break off into groups of two to three players to become the management team of their own airline. After drawing up their strategy for the company, they make five decisions on a quarterly basis: how many planes to buy, how many customer service managers to hire, how much to spend on marketing, what fare to charge, and what scope of services to offer. After entering their decisions, participants receive reports which keep track of information such as cash flow, stock price, and employee morale. In the course of a few hours, teams are able to run the simulator several times, testing and debating various strategies. “Nearly all teams experience bankruptcy at least once,” Sterman estimates. “But by the end of the session nearly all of them find a successful strategy.”

The discussion that follows the game is “much deeper than the case discussion at the beginning of the workshop,” he notes. “Participants are more aware of the side-effects, counter-reactions, time delays, and trade-offs they face.” For example, participants often suggest during the initial discussion that People Express could have succeeded if it “maintained service quality.” But after playing the game, show a better understanding of the time lags and counter pressures that may frustrate quality improvement programs. They discover that even if service improves, People Express’ low fares attract still more would-be customers, causing overbooking, more busy signals on the reservation lines, and other problems which drag service quality down again.

The success of the People Express Simulator, Sterman believes, is in part due to its experiential format. “Participants are rarely able to identify and integrate all of the subtle dynamics of the company without experiencing them as they run their own airline in the simulator.”

Insight vs. Hindsight

Interestingly, Sterman created the simulator model before People Express’ dramatic collapse, suggesting the possibility of using flight simulators to pinpoint problems or lapses in an organization before they become life-threatening. In contrast to a typical case study that is retrospective in nature, management flight simulators encourage taking a prospective view of a case. Instead of stopping at the question “what happened?” players test out alternate strategies that pursue the question “what could happen?” By formulating and testing many different strategies, players gain greater insight into the case.

That type of thinking is at the heart of other flight simulators. The Hanover Insurance Claims Learning Laboratory (Systems Thinking in Action, April/May 1990) features a flight simulator that was created to help claims managers reevaluate the way they allocate resources in the departments. Other management flight simulators currently under development revolve around specific issues — service quality management, real estate development, and new product lifecycle management — rather than companies.

Learning from Prototypes

“In order to learn how to create learning organizations, managers need to study prototype organizations — ones that have gone a little way towards become learning organizations but have failed.” Peter Senge argued in his book The Fifth Discipline. People Express Airline, he said, was one such prototype. It had some of the components of a learning organization — shared vision and a commitment to personal mastery — but no concept of the whole system. With the aid of tools like management flight simulators, managers can now study and learn from innovative organizations such as People Express.

For information about obtaining a copy of the People Express Management Flight Simulator, contact John Sterman, E52-562, MIT Sloan School of Management, 50 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 02139, (617) 253-1559., FAX (617) 253-6466

Further reading: Peter Senge and Colleen Lannon, “Managerial Micro Worlds,” Technology Review, July 1990. Jolie Solomon, “Now, Simulators for Piloting Companies,” Wall Street Journal, July 31, 1989.