“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…” wrote Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities. Life often seems full of such paradoxes. When we arc busy earning lots of money, we have little time to enjoy it. When we do have time available, it seems we don’t have much money to spend. A rapidly growing company finds itself too busy to invest its profits in internal development, but when sales begin to slow, it no longer has the resources (money and people) to spend on needed improvements. The “best of times” for investing in resource development always seems like the “worst of times” for actually carrying out such plans, and vice versa.

The Structure

'Limits to Success' Template

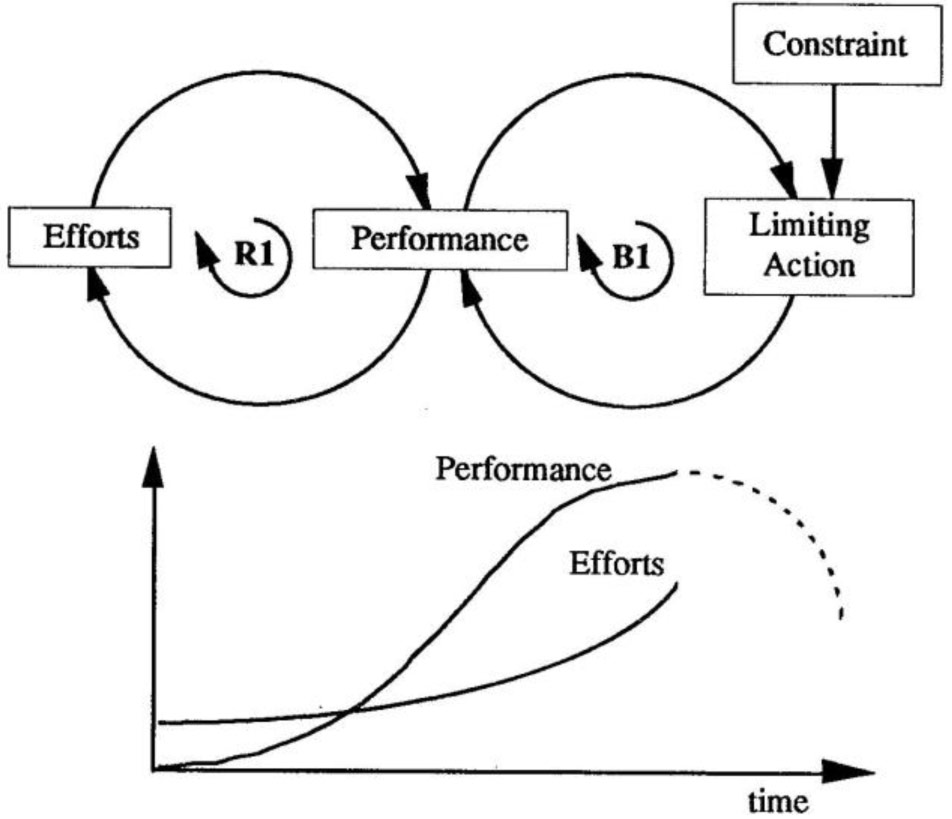

Recognizing this paradox can help individuals and companies avoid the “Limits to Success” trap. In a typical scenario (see “Limits to Success Template”), a system’s performance continually improves as a direct result of certain efforts. As performance increases, the efforts are redoubled, leading to even further improvement (loop R1). When the performance begins to plateau, the natural reaction is to increase the same efforts that led to past gains. But the harder one pushes, the harder the system seems to push back: it has reached some limit or resistance which is preventing further improvements in the system (loop B1). The real leverage in a “Limits to Success” scenario doesn’t lie in pushing on the “engines of growth,” but finding and eliminating the factor(s) limiting success while you still have time and money to do so.

In a rapidly-growing company, for example, initial sales are spurred by a successful marketing program. As sales continue to grow, the company redoubles its marketing efforts and sales rise even further. But after a point, pushing harder on the marketing has less and less effect on sales — the company has hit some limit, such as market saturation or production capacity. To continue its upward path, the company may need to invest in new production capacity or explore new markets.

Diets and Weight Loss

Examples abound where rapid success is followed by a slowdown or decline in results. Dieters usually find that losing the first ten pounds is a lot easier than losing the last two, and losing weight the first time around is a lot easier than losing it the next time.

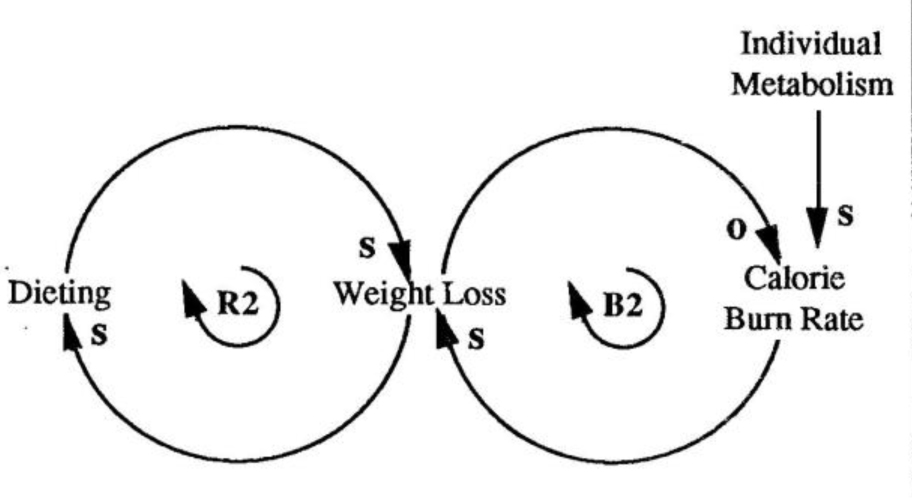

On a diet, eating less leads to weight loss, which encourages the person to continue to eat less (loop R2 in the “Dieting Bind” diagram). But, over time, the body adjusts to the lower intake of food by lowering the rate at which it burns the calories. Eventually the weight loss slows or even stops. The limit here is the body’s metabolic rate — how fast it will burn the food. To continue losing weight, the person needs to increase the metabolic rate by combining exercise with dieting.

But pushing equally hard on exercising isn’t the full answer either, since intense exercise burns simple sugars and not the stored fat that is the real target for weight loss. Intense exercise is counterproductive towards the dieter’s goal because it increases appetite while only temporarily raising the metabolism. The real leverage is to engage in steady exercise such as long, brisk walks that will increase the metabolic rate to a permanently higher level.

Service Capacity Limit

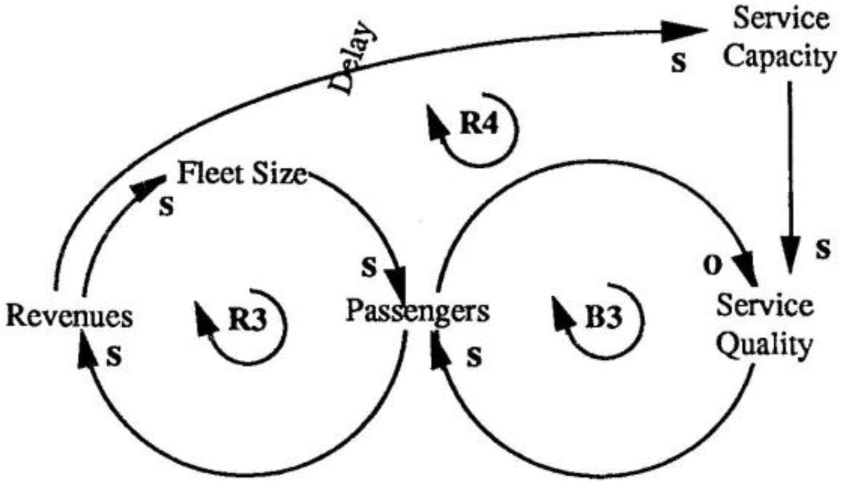

People Express airlines is one of the best-known casualties of the “Limits to Success” archetype (see “‘Flying’ People Express Again,” November, 1990). Its tremendous growth was fueled by a rapid expansion of fleet and mutes along with unheard of low airfares. As the fleet capacity grew, People Express was able to carry more passengers and boost revenues, allowing it to expand fleet capacity even more (loop R3). The quality of its service was initially very good, so the positive experience of many fliers increased word-of-mouth advertising and the number of passengers.

The Dieting Bind

The “engine of growth” at People Express was seen as physical capacity — expanding fleet size, employees and routes. But its “limit to success” was service capacity — the ability to invest time and money in training its employees — which became more difficult to sustain as the company grew (loop R4).

The number of passengers flown eventually outstripped the airline’s capacity to provide good service. As a result, quality suffered and it began losing passengers (loop B3). When competitors began matching low rates on selected routes, People Express’ market competitiveness suffered even more. Focusing only on the reinforcing side of the structure turned rapid growth into a tailspin, contributing to the airline’s demise.

Simply hiring more employees was not the answer to People Express’ service capacity problems. Similar to the dieter’s reliance on intense exercise, it only masked the real need for the steady long-term commitment to hire and train the necessary people to bring service quality up to a high and sustainable level.

Using the Archetype

The “Limits to Success” archetype should not be seen as a tool to be applied only when something “stalls out.” It is most helpful when it is used in advance to see how the cumulative effects of continued success might lead to future problems. When the times are good and everything is growing rapidly, we tend to operate with an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” attitude. By the time something breaks, however, it may be too late to apply a fix.

Limits to Passenger Growth

Using the “Limits to Success” template can help highlight potential problems by raising questions such as “what kind of pressures are building in the organization as a result of the growth?” By tracing through their implications, you can then plan for ways to release those pressures before an organizational gasket blows.

“Limits to Success” and other templates have been developed over the years through the efforts of many system dynamicists, including Peter Senge, John Sterman, Michael Goodman, Jennifer Kemeny, Ernst Diehl. and Christian Kampmarut. The use of the term “archetype” was first coined by Peter Senge in his book, The Fifth Discipline, Doubleday, 1990.