Iwant you to create the new print ad campaign. Here’s a copy of what we’ve done in the past and a summary of my thinking about what we need. Your deadline is in eight weeks.”

Eight weeks later . . . “Let’s see what you’ve come up with. No, this is all wrong. In the first place, these ads are too small. Start over. Make them full-page and full-color. Put the headline here, the body text here, and the logo there. You need a new photograph — this one isn’t dramatic enough. Use softer lighting here. This is better, closer to what I want. This works.

“Don’t worry. You’ll get the hang of what I’m looking for — you know, what works with our customers.”

Many of us remember a time early in our careers when a manager coached us on an assignment. Although the details of the conversation varied, our boss inevitably gave us “words of wisdom” or “constructive criticism.” He or she expected us to learn in the time-honored tradition of apprenticeship, in which an expert instructs, monitors, and corrects the learner on how to do a task a certain way.

This traditional model contains a powerful implicit assumption by managers: “I’m the expert. I’ll tell you what you need to know. You’re here to learn from my experience. If you question me, you question my expertise and authority.” Unfortunately, this perspective locks both the manager and the employee into roles that don’t always serve the employee’s learning or the manager’s efforts to teach and guide. The teacher’s “performance” and expertise may take on greater importance than the learner’s improvement.

Timothy Gallwey, whose “Inner Game” philosophy has challenged most traditional coaching methodologies, often cites a valuable insight he gained about the roles of teacher and learner early in his career as a tennis pro. During a lesson, he was astonished when the student learned something before Gallwey had a chance to teach it to him. Gallwey remembers his exasperation as he thought, “How dare he . . . I haven’t shown him that yet!” Reflecting on it later, he realized that he had been more concerned with his own teaching than with the student’s learning.

What Gallwey discovered was simple — but not easy — for coaches, managers, and leaders to accept: When a coach concentrates on facilitating a person’s learning instead of on teaching, the coachee’s performance can undergo an almost magical transformation. Natural learning, based on the coachee’s learning style, happens quickly and easily — much the way we learned to walk or ride a bike. Because this kind of learning experience promotes relaxed concentration and enables us to create our own high-quality feedback, we stop trying so hard and perform almost unconsciously at increasingly effective levels. Over the years, Gallwey and others have shown that this change in focus can be effective in enhancing individual and team performance and learning in business, sports, and even music.

Partnership Coaching Defined

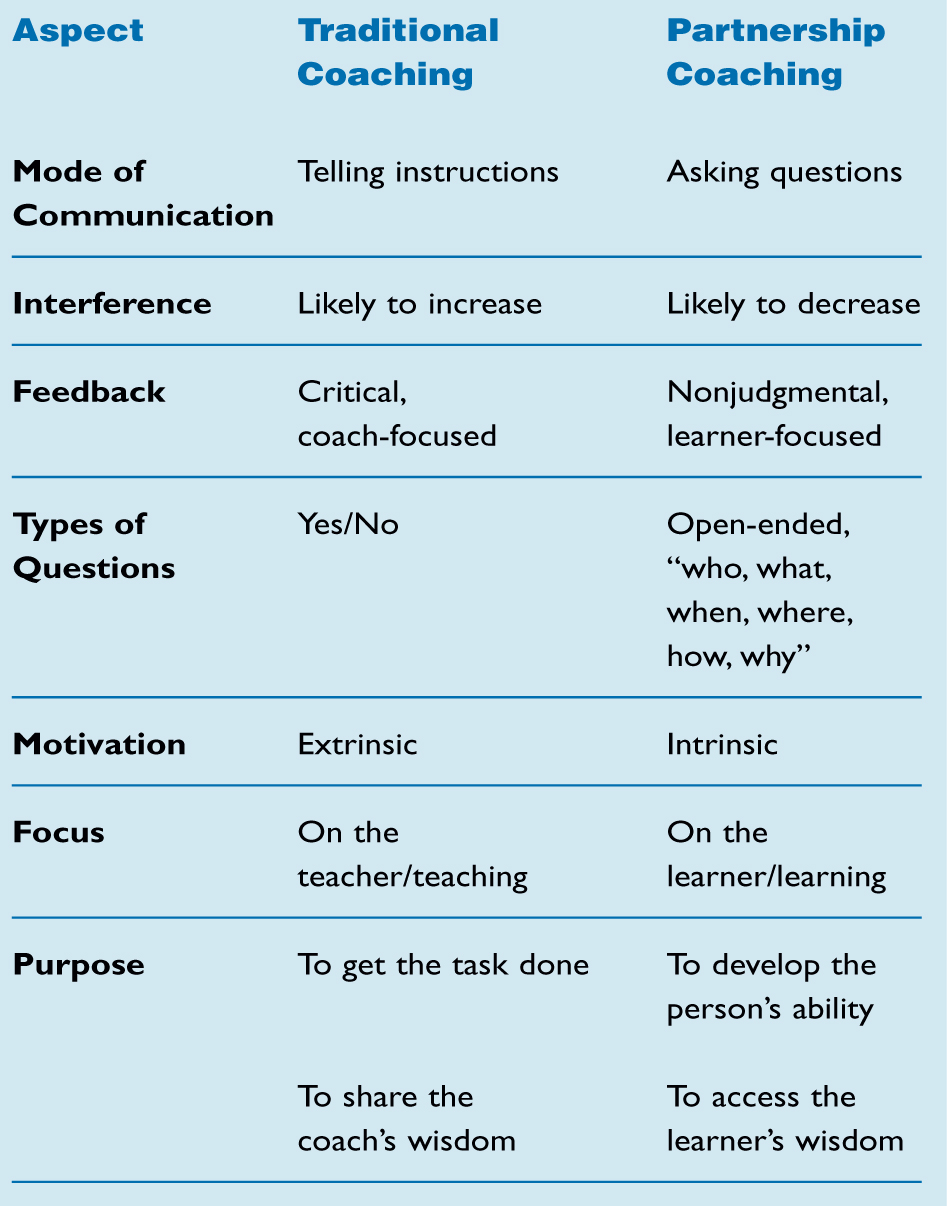

Effective coaching is a partnership between coach and coachee, expert and novice — a partnership whose purpose is to facilitate learning, improve performance, and enable learners to create desired results (see “Traditional Versus Partnership Coaching”). In partnership coaching, one individual works to support the learning and actions of another person or a team. Following this model, managers help people achieve what they want — through careful listening and gentle guidance — rather than tell them what they need to accomplish or to know. Shifting from a focus on teaching to a focus on learning requires a manager or coach to:

- Ask open-ended questions that focus the person’s attention on critical, relevant details rather than tell her what the coach knows.

- Create an environment that reduces interference — or negative self-talk by the learner — which can reduce the quality of the learner’s thinking and actions.

- Understand the difference between constructive criticism and edible — or usable — feedback and to make feedback learner-focused rather than teacher-focused.

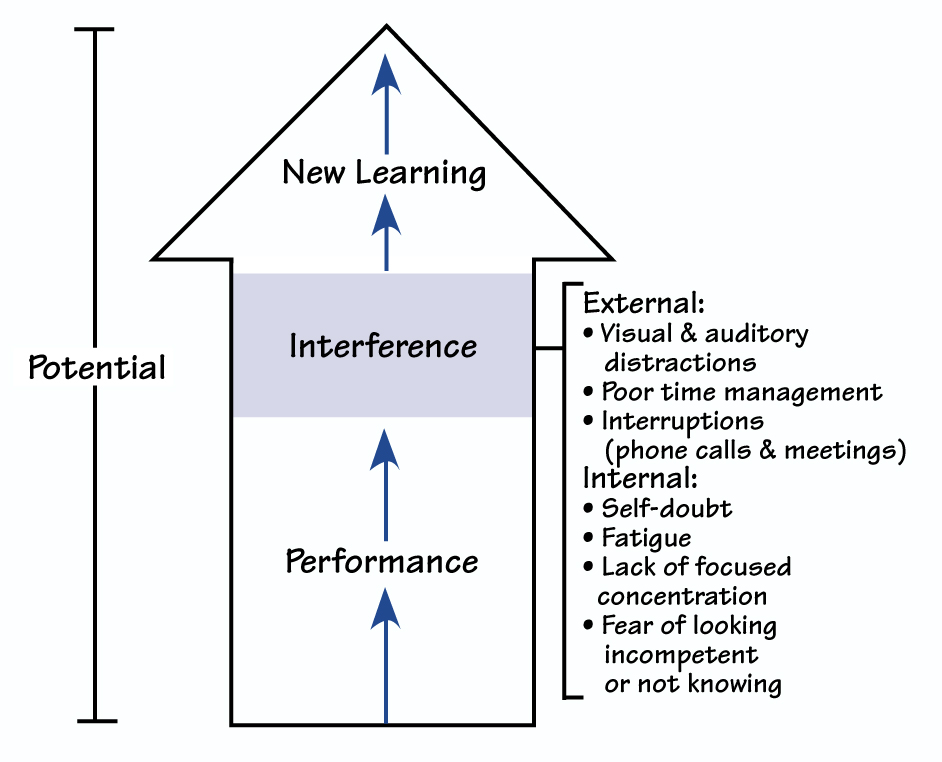

INTERFERENCE MODEL

The Interference Model shows how, by reducing interference, individuals can dramatically and immediately improve their performance without learning any new skills. In an interference-free state, new learning is natural and easy

The Limitations of “Telling”

As shown in the opening example, the traditional structure used for conveying expertise and advice emphasizes telling. Although good, clear instructions are vital to the successful completion of a task, most managers find it difficult to convey information in a way that enhances a learner’s performance. In the telling mode, a coach usually assumes the employee understands what he is saying, but often the employee goes away feeling confused at best, and mistrusted and disrespected at worst.

Our informal polling of approximately 1,000 middle to senior-level managers indicates that executives use telling as a means of communication an average of 85-90 percent of the time. And yet, at least five conditions must be met for the telling approach to be effective. 1. The coach has to know exactly how to do the task. 2. The coach has to be able to articulate clearly what she does know. 3. The other person has to understand what the coach is saying. 4. The other person has to be able to translate those instructions into action. 5. The other person has to want to do the task. If one or more of these conditions is missing — which is often the case — the odds of a coach’s successfully transferring know-how to a learner are low. Moreover, the coach has likely wasted her own time, the other person’s time, and the company’s money.

According to the British author and business coaching expert Sir John Whitmore, “To tell denies or negates another’s intelligence; to ask honors it.” Yet shifting from telling to asking isn’t the only change coaches need to make in order to improve their skills; they also need to learn to ask effective questions.

The Anatomy of an Effective Question

Effective questioning uses the principle of creative tension to set up conversational structures that promote learning. According to Robert Fritz, a structure seeks to resolve the inherent tension within it, much like a stretched rubber band seeks to return to its original state. Asking a question sets up a tension that is resolved by an answer; for example, when asked “How are you?” we feel compelled to resolve the tension in the linguistic structure by responding.

A good question helps individuals put aside their assumptions regarding the correct or right answer and lets more reflective and flexible responses fill the void. The word question itself suggests a “quest” for something, inviting the respondent to create or find an answer. Thus, an effective or powerful question creates a structure in which an individual or group feels compelled to seek a resolution. In addition to providing creative tension, effective questions:

- Are nonjudgmental.

- Are open-ended (who, what, when, where, why, and how) instead of closed (requiring a yes or no answer).

- Raise awareness of the learner’s goals and current reality by broadening his perceptions.

- Reduce interference by focusing the learner’s attention.

- Make feedback “edible” — or easier for a learner to hear and use.

- Lead to deeper questions and more reflective and expansive thinking by the learner.

A powerful question asked with the wrong intention (such as getting the person to agree to something) isn’t as effective as a question posed from a place of genuine reflection and interest. When people feel cornered and manipulated, they are likely to be less forthcoming and thoughtful with their responses. “Yes/no” questions such as “Well, did you ever think about . . . ?” or “Wouldn’t you agree that . . . ?” can come across as accusatory because these queries often contain hidden assumptions about the speaker’s mental models regarding the best decision or the right answer. Such closed-ended questions can make people feel defensive and undermine a partnering relationship.

Surprisingly, tone of voice and body language carry approximately 92 percent of the meaning in conversations; the words themselves convey only 8 percent. The power of a good question can thus be lost if a manager comes across as condescending, negative, arrogant, or even overly solicitous. A leader who is well intended can still create crippling self-doubt within an employee by asking a good question with the wrong tone or inflection.

Overcoming Interference

In his article, “The Inner Game of Work: Building Capacity in the Workplace” (V8N6), Gallwey discusses the concept of internal interference and how it creates obstacles to learning (see “Interference Model” on p. 1). Gallwey defines interference as “the ways that we undermine the fulfillment or expression of our own capacities.” Interference can be internal or external; it impedes our performance by preventing us from concentrating and from receiving ongoing feedback. Gallwey has found that reducing interference can dramatically improve a person’s performance. Learning happens naturally when a person isn’t distracted by negative thoughts and can focus on what he is doing.

TRADITIONAL VERSUS PARTNERSHIP COACHING

The key to reducing interference lies not in diagnosing it, but in asking questions that move learners’ attention away from judging their own performance to concentrating on the relevant details of the activity they are attempting to perform. For example, when an employee appears flustered because she doesn’t know how to resolve a problem, asking her what she is noticing about the situation or the problem, and what is and isn’t working toward resolving it, can increase her self-awareness and reduce her self-doubt, enabling her to focus calmly on the issue at hand. This self-awareness gives coachees pure, nonjudgmental, and noncritical feedback about what is actually happening. At the same time, coaches need to ask themselves, “Am I increasing or decreasing interference in this conversation?”

What, then, might the session in the opening example have sounded like if the coach had used questions to reduce the coachee’s internal interference and increase her focus?

“I want you to create the new print ad campaign. Here are copies of what we’ve done in the past. What do you think about the strategy and format we used? Here’s data from focus groups and information on how well the ads pulled. What do you think we could have done to increase those numbers? Our deadline is in eight weeks. How long do you think you will need? When can you tell me if this deadline is realistic?”

First coaching meeting: “I’ve had a chance to look at the first version of the new print ad campaign. First, I’m curious about your thinking behind this strategy. What about this style and format appeals to you? What about this approach do you think will appeal to our customers? What about these ads works better than our previous campaign?

“What concerns do you have, if any, about this strategy? Where do you think the trends for print ads are headed? Is there anything you’d like to do differently, given more time or money?

“I’m a little concerned about the size of the ads and the lack of color, but maybe I’m underestimating the impact. I guess I need to know more before I’ll feel completely comfortable with changes that feel this drastic. How will our customers respond to such changes? Will the ads cost more or less to produce? What is the impact on our overall budget?”

In the example above, the manager expresses little judgment regarding what is right or wrong, good or bad, about the proposed ad campaign. She asks open-ended, not yes or no, questions. Her intention, style, and tone convey a desire to learn the employee’s perspective and to help him think for himself and draw his own conclusions. The employee in this scenario is likely to experience much less interference than in the scenario at the beginning of the article, and thus should experience greater learning, clearer thinking, and improved performance. The responsibility for learning is placed on the employee — not on the manager. This employee will probably feel that the manager is “on his side,” supporting his development and achievement of desired results.

“Edible” Feedback

One of the most important ways to improve an employee’s performance and create structures for learning is clear, relevant feedback about current reality — what’s working and not working about the individual’s actions. The traditional feedback model consists of an expert offering so-called “constructive” criticism. But how do people generally feel when they hear, “I have some feedback for you”? Their level of interference usually increases. They may think, “Oh, no . . . I’m about to be judged, slam-dunked, pulverized. I hope I can defend myself, or maybe even blame someone else. Let’s get this over with, or maybe I’ll just zone out.” Meanwhile, they generally don’t hear or consider the coach’s observations simply because they are not edible.

An edible suggestion is one that the coachee can actually take in and digest because it doesn’t overload her with too much negative information, too much advice, or too many suggestions to remember or internalize. This feedback model shifts the focus away from the traditional mode of the manager telling the employee what went right and wrong to one in which the employee discovers for herself what she learned. By helping the performer “debrief her own perceptions of what did and didn’t work, the coach leverages our tendency to believe our own data and observations, rather than those provided by others.

Feedback should do exactly what the word says: Feedback information that nourishes the performer, increases self-awareness and focus, and allows him to internalize useful data for learning. Providing feedback in this manner fosters learning and improvement that are intrinsically, rather than extrinsically, motivated (see “How to Give Edible Feedback”). Performer-based feedback also creates trust and better, more reflective working relationships, because the data is more easily digested. This focus enables the coach to function as a mirror, reflecting back the appropriate, relevant information in a nonjudgmental way.

HOW TO GIVE EDIBLE FEEDBACK

- Ask the person what worked for her during the meeting (the conversation, the presentation, the sales call, etc.).

- Ask her what didn’t work as well for her.

- Ask her what she might want to consider doing differently next time.

- Offer any feedback you might have about what worked and didn’t work or suggestions for change only after checking with her to be sure she wants it and that this is a good time for her to hear it.

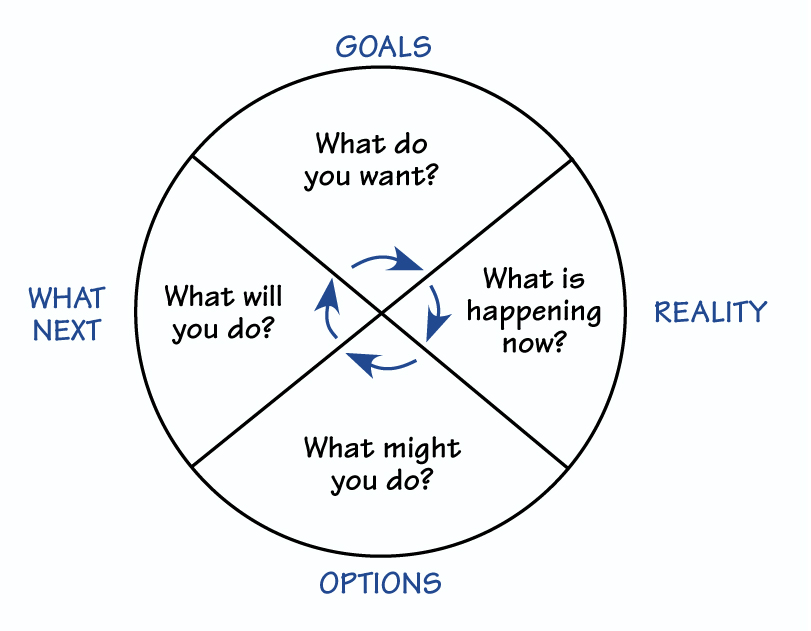

The “GROW” Model of Coaching

Partnership coaching involves shifting one’s mind-set from teaching, training, and controlling to asking coachees for their desired outcomes and ideas for achieving them; reducing coachees’ internal interference; and learning to give useful, edible feedback. All these elements are woven into a process for conducting a successful coaching session described by Sir John Whitmore in his book, Coaching for Performance. His “GROW” model can help guide coaching conversations to more meaningful and realistic resolutions (see “The GROW Model” on p. 5). Although there are many effective ways to coach in a partnership style, the GROW model provides a useful framework in which the coach guides the coachee toward articulating her goals and achieving desired results. By using effective questions in a nonjudgmental tone, the coach shows respect for the coachee and helps her to take ownership for determining the path to reach her goal.

G=GOALS

The coach and coachee agree on session goals and long-term goals. To set session goals, the coach asks questions such as:

- What would you like to accomplish in the time we have available?

- What would make this time well spent?

- What would you like to achieve today? To set long-term goals, she asks:

- What would ultimate success look like to you?

- If you could create anything you want, what might that be?

R=CURRENT REALITY

Centering on current reality means describing the situation as accurately as possible, challenging assumptions that might be blocking more effective thinking and action, and raising awareness of the relevant details of what is currently happening. Good coaching involves following the coachee’s interests and thoughts and exploring what he has tried so far, without judging. Questions about current reality might include:

- How do you know your perception of X is accurate? How can you be sure?

- Whom else might you check with to get more data about the larger perspective?

- What have you tried so far?

- What are your beliefs about this particular situation? This person? The other department?

O=OPTIONS

The first challenge here is to help the coachee create as many options for potential actions toward the goal as possible without judging the ideas’ merit or practicality. The focus is on the quantity — not quality — of options. Building on the ideas and then choosing among them comes later. The idea is for the learner to stretch the boundaries of his thinking and to use creativity to unlock options he might not otherwise consider.

Once the coachee completes his list of options for action, the coach may offer any ideas she might have thought of while the coachee was brainstorming. Examples of coaching questions at this stage might include:

- If money, time, and resources were no obstacle, what options might you choose?

- What are all the different things you might do?

- What else might you do? What else?

- If you were to ask X person, what might he or she suggest?

- Who else could help?

- What might some “sky is the limit” thinking sound like?

- Would you like to hear some ideas that have occurred to me while you were brainstorming?

At some point, the coachee’s well of ideas will run dry. Now he should look over the list and select those options that seem most promising. The coach can help clarify priorities by asking questions such as:

- Which options would you like to explore further or take action on right away?

- Which would you be willing to implement?

- How would you rate these options from high to low?

- Where would you like to begin?

W=WHAT’S NEXT?

This is the stage for committing to action — stating an intention that is time-phased and observable, identifying potential obstacles, and aligning support from collaborators. Possible questions might include:

- What are you going to do and by when?

- What’s next? What steps are involved?

- How might you minimize the obstacles?

- What might be some unintended consequences of taking these actions?

- How will you collect data for feedback over time as you progress?

- On a scale of one to ten, how certain are you that you will do this?

Self-Coaching

One of the remarkable things about partnership coaching is that managers don’t have to be subject matter experts in order to coach others who are — they just have to be expert coaches. Sometimes, having less expertise on the subject than the coachee frees an instructor from needing to share his knowledge; this “knowing” can get in the way of asking good questions.

Coaches who want to improve their skills can solicit feedback as part

THE GROW MODEL

The GROW Model illustrates the process of helping others clarify what they want, what they have now, options for achieving results, and a plan for action.

of every learning session by asking learners:

- What about the session worked well?

- What didn’t work as well?

- What might I do differently next time to support you more effectively?

Coaches can also guide themselves during a coaching conversation and gain additional learning afterwards by asking:

- What’s happening right now?

- Where is my coachee’s focus?

- How much interference is she experiencing? Where is it coming from?

- When I made that statement, what happened with her body language?

- What cues does she give me to sit quietly and let her think?

- What judgments appeared in my thinking?

- On a scale of one to ten, how would I rate our level of partnership?

- What worked and didn’t work for us in that coaching session?

These questions give managers the opportunity to make adjustments, test assumptions, and experiment with new possibilities.

Leveraging Partnership Coaching

At its most effective, partnership coaching is simply a generative conversation in which the coach asks nonjudgmental, open-ended questions that sharpen the coachee’s focus and increase her awareness of goals, current reality, and possible options for action. In a natural and easy way, it reduces interference and structures feedback for intrinsically motivated learning. This coaching model can leverage learning for individuals, teams, and organizations by helping them improve performance more quickly than in traditional forms of coaching.

As partnership coaching becomes part of an organization’s culture, every leader becomes a steward of learning and a facilitator of performance. Learners come to trust that managers are truly on their side, supporting their learning and development as a partner and not as a disciplinarian. Partnership coaching can be a powerful tool for implementing the principles of organizational learning by facilitating personal mastery, team learning, and shared vision.

Diane Cory is a facilitator, coach, and consultant whose areas of expertise include organizational learning, servant leadership, storytelling, creativity, and coaching.

Rebecca Bradley (Rebecca@ partnershipcoaching.com), president of Atlanta-based Partnership Coaching, Inc.™, is an executive coach and consultant whose focus is helping individuals and teams improve performance.