Just as fire requires fuel, heat, and oxygen to exist, the ability to perform effectively derives from three factors: capability (fuel), motivation (heat), and opportunity (oxygen). We can assume that the elite women figure skaters at the 2002 Olympic Winter Games were adequately skilled, prepared, and motivated. They also all performed under the same rules and conditions. Their circumstances differed, however, in the psychological challenges that they faced.

OLYMPIAN PERFORMANCE PRESSURE

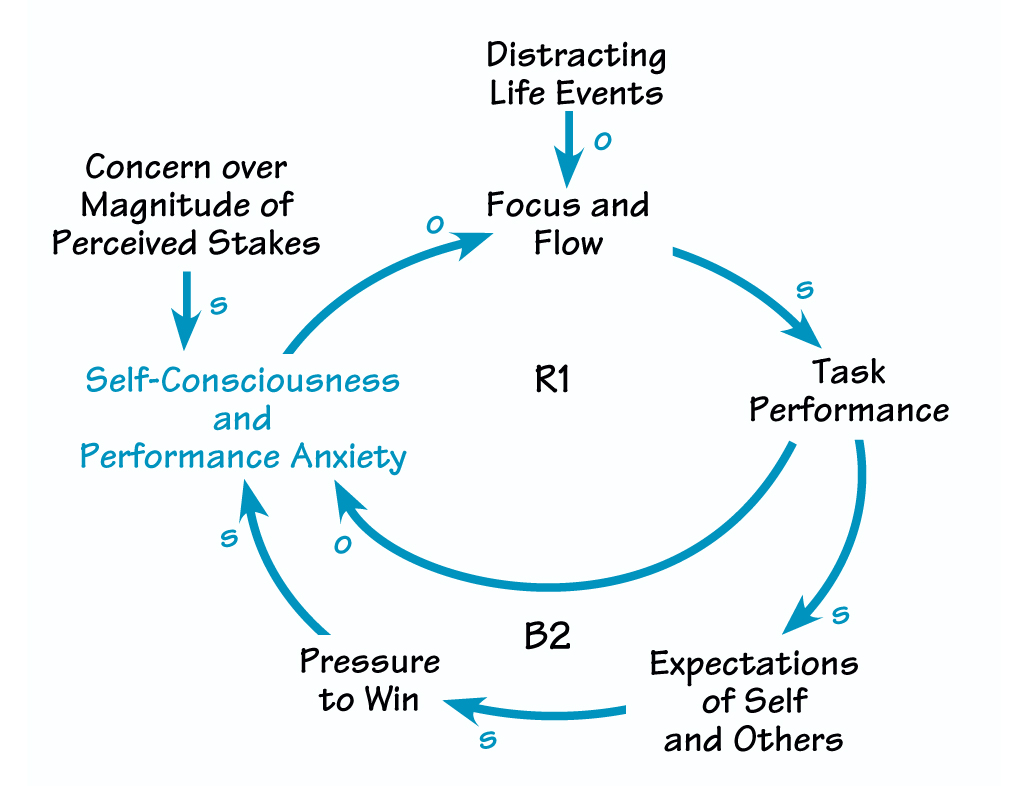

Many factors can distract a performer’s focus and disrupt her flow. Fueling these distractions and disruptions are outside forces such as a competitive reward structure, significant rewards and punishments, and the expectations of others. A vicious cycle (R1) operating within the performer’s psyche can exacerbate the effects of the outside forces. A balancing loop (B2) turns the performer’s own past successes against her.

Focus and Flow

The psychology of performance revolves around focus and flow. Focus represents attention to a single task. Our performance suffers if our focus is diffused by distractions, such as life events, concern for the consequences of success or failure, or self-consciousness. Flow is the execution of a well-learned routine without explicit attention to the individual steps of the task. If we’re anxious about performing well, we end up riveting our attention on each individual component rather than trusting our experience and training to see us through. But doing so disrupts our flow and can degrade performance. Even worse, when a performance is going poorly, our levels of self-consciousness and anxiety rise even further, leading to more distraction and disruption (see R1 in “Olympian Performance Pressure”).

Even past successes can indirectly increase performance anxiety, because they serve to raise others’ expectations—and boost the amount of pressure on the athlete (B2). Success at the Olympic Games holds the prospect of product endorsements, performance contracts, and many other rewards. Failure at the Olympics occurs on a world stage like no other, after sizable investments of time, effort, and money. The magnitude of these rewards and punishments raises the perceived stakes and generates intense scrutiny by others, especially the media.

In addition, by design, competition for prizes limits the number of successful outcomes, which can also raise performance anxiety. However many fine performers participate in the Games, there are only three medal positions in any single event. Further, high expectations can bound a performer’s definition of success; for instance, if he expects—and others expect him—to finish first, even a silver medal will seem like failure. If the skater only hopes to challenge the leaders, the number of outcomes that he might consider successful is much greater.

Leverage in Lower Expectations

When 16-year-old Sarah Hughes stepped onto the ice for her long program, she was the unknowing beneficiary of the dynamics discussed here. Disappointed by her poor short program—which left her in fourth place before the final event—this relative newcomer to world-class competition lowered her expectations for winning a medal and avoided the pernicious effects of the B2 loop. Further, Hughes had not received the same degree of media scrutiny as did the leaders, Michelle Kwan and Irina Slutskaya. The expectations placed on her were moderated, she was less self-conscious than she might have been, and her definition of success broadened to include simply enjoying the experience to the fullest.

On the other hand, Kwan and Slutskaya were almost unanimously expected to wage a high-stakes battle for the only outcome that either of them could count as success—the gold medal. Both faltered in the long program, presumably falling prey to the dynamics of the R1 and B2 loops, and they finished behind gold medalist Hughes, who gave the performance of her life.

This discussion does not detract from Hughes’ achievement. She still had to skate—and she delivered a beautiful, error-free program. However, because of these dynamics, Hughes had a psychological advantage over Kwan and Slutskaya. And now that Hughes has won one of the world’s premier skating events, she will not have that advantage the next time she competes. Since she has no control over the expectations of others, the glare of the spotlight, or the limited number of winners allowed, she can only strive to duplicate the mental state she had going into her Olympic long program—and focus purely on the joy of skating.

Richard A. White is the founder and president of Orchard Avenue, a consulting firm dedicated to helping individuals and organizations achieve greater levels of effectiveness.