In the 1970s, diversification was the rage. But by the early 1980s, serious doubts had surfaced in the Shell Group about the wisdom of moving the business portfolio away from oil and gas. Equal doubts persisted, however, about the long-term future of these resources. The company’s leaders began to ask themselves, “Is there life after oil, or at some point will we be forced to return the company to the shareholders?”

To answer this question, Shell’s planners set out to study other companies that had weathered significant changes and survived with their corporate identity intact. In particular, they were looking for companies that were older than Shell (100 years or more) and that were as important in their own industries. After some research, a few examples started trickling in: Dupont, the Hudson Bay Company, W.R. Grace, Kodak, Mitsui, Sumitomo, Daimaru. Forty companies were eventually identified, of which 27 were studied in detail.

Keys to Longevity

Of the tens of thousands of companies that had existed at the beginning of the 19th century, why did so few remain by 1980? And what had these few done to survive? Shell’s planners found that, in general, the 27 long-established companies shared a history of adaptation to changing social, economic, and political conditions. The changes within those companies appeared to have occurred gradually, either in response to opportunity or in anticipation of customer demand. The companies shared some additional characteristics that could explain their durability:

- Conservative Financing. These companies had an old-fashioned appreciation of money. They did not make business decisions based on intricate financial deals using other people’s money. Rather, they understood that money-in-hand gave them the flexibility to take advantage of opportunities as they arose.

- Sensitivity to the Environment. The leaders of these companies were outward looking, and the companies were connected to their external environment in ways that promoted intelligence and learning. As a result, they were sensitive to changes and developments in the world. They saw changes early, drew conclusions quickly, and took action swiftly.

- A Sense of Cohesion and Company Identity. In numerous cases, the Shell researchers found a deep concern and interest in the human element of the company–a quality that was somewhat surprising for the times. Employees and management seemed to have a good understanding of what the company stood for, and they personally identified with it. Quite often, this value system had been brought in by the founder, and was occasionally formalized in a kind of company constitution.

- Tolerance. The companies had made full use of what we would call in modern terms “decentralized structures and delegated authorities.” They did not insist on relevance to the original business as a criterion for selecting new business possibilities, nor did they value central control over moves to diversify. In other words, they had high tolerance for “activities in the margin.”

Businesses: Economic Entities or Organisms?

The Shell planners summed up their profile of these corporate survivors as follows: “They are financially conservative, with a staff that identifies with the company and a management which is tolerant and sensitive to the world in which they live.” This definition of a successful enterprise is quite different from the one I was taught in college, which portrayed businesses as rational, calculable, and controllable. Production, we learned, is a matter of costs and price. Costs are associated mostly with labor and capital—production factors that are interchangeable. If you have trouble with labor or if it is too expensive, you simply replace it with capital assets. For aspiring corporate leaders, this description of their future workplace painted a reassuring and comforting picture.

The real world, we discovered, was quite different. The economic theories offered at school made no mention of people, and yet the real workplace seemed to be full of them. And because the workplace teemed with people, it looked suspiciously as if companies were not always rational, calculable, and controllable.

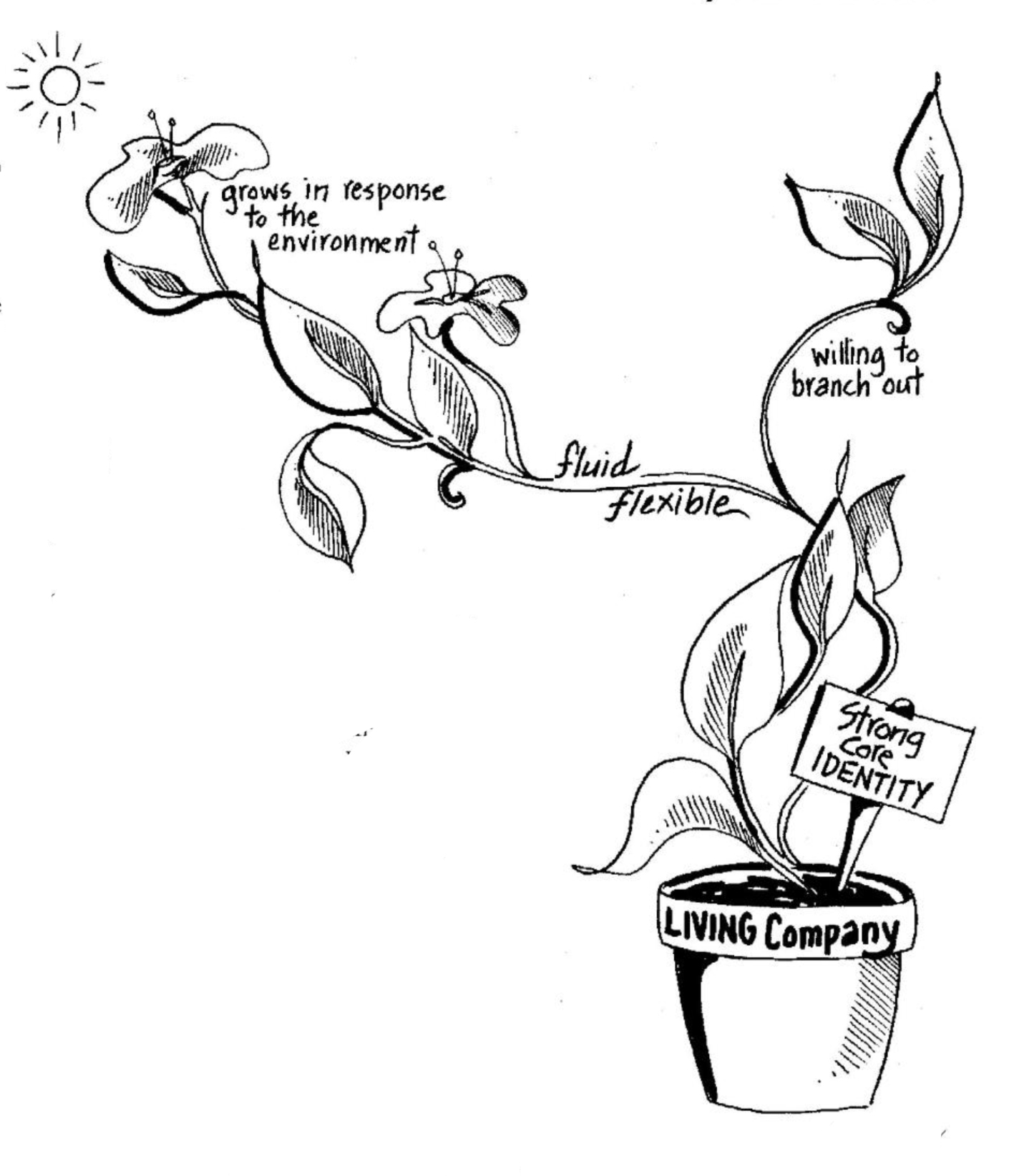

The Shell study, which described within these companies a “struggle for survival, maintaining the institution in the face of a constantly changing world,” supports this view that companies are perhaps more organic than economic in nature. Of course, the long-term survivors had to control costs, market their product, and update their technology, but they tended to see these basic functions as secondary to the more important considerations of life and death. These companies not only employed people who sometimes proved uncontrollable or irrational; the companies themselves behaved as if they were alive.

What if we were to look at companies as “living systems,” rather than mere economic instruments created to produce goods and services? Would that viewpoint change our ideas about how to manage a business, or perhaps offer an explanation of why some companies endure and so many die young?

Though this hypothesis certainly does not apply to all companies—many do operate as if the production of goods and services is a purely economic problem—it may offer new insights into some corporate phenomena. In particular, I’d like to explore how “living” versus “economic” companies—and the management of them—differ in three basic respects:

- the role of profits and assets

- the amount of steering and control from the top (in decisions such as diversification, downsizing, or expansion)

- the way the company creates and shapes its human community

Role of Profits and Assets

In the 27 companies Shell studied, the main driving force seemed to be the firm’s own survival and the development of its potential. History shows that these companies engaged in a business—any business—so long as doing so sustained them as viable work communities. In fact, over their long lifetimes, each one changed its business portfolio at least once.

For example, Stora, a company that was not included in the original Shell study, began as a copper mine in central Sweden around the year 1288. During the next 700 years, new activities replaced the old “core” business: the company moved from copper to forest exploitation, to iron smelting, to hydro • power, and, more recently, to paper and wood pulp and then chemicals.

Dupont de Nemours started out as a gunpowder manufacturer, became the largest shareholder of General Motors in the 1930s, and now focuses mostly on specialty chemicals. Mitsui’s founder opened a drapery shop in Edo (Tokyo) in 1673, went into money-changing, and then converted the company into a bank after the Meiji Restoration in the 19th century. The company later added coal mining, and toward the end of the 19th century it ventured into manufacturing.

In retrospect, each one of these portfolio changes might seem Herculean. But for the people running these enterprises at the time, the shift may have been imperceptible at the outset. At some stage, these companies may have thought of themselves as bankers, while a later generation of their leaders viewed themselves as manufacturers. Such changes cannot come about if a company regards its assets as the essence of its existence.

This fluidity demonstrates an important attitude toward whatever “core” business the company happens to be doing at any moment. All businesses need to make a profit in order to stay alive, but neither the core business—nor the profits from it—must be the driving force. Businesses need profits in the same way that any living being needs oxygen: we need to breathe in order to live, but we do not live in order to breathe.

This attitude is quite different from the “economic” company, which engages in a particular business to make profits or to maximize shareholder value. For such a company, the core business is the essence of life, and profits are its purpose. This position can lead to the belief that the present asset base represents the essence of the company—that the company’s purpose in life is to exploit this particular set of assets. In a crisis, such a business will scuttle people rather than assets to save its “balance sheet” (which quite appropriately records only physical assets).

Businesses need profits in the same way that any living being needs oxygen: we need to breathe in order to live, but we do not live in order to breathe.

The logical endpoint of this thinking would be: “We will liquidate the company and return the remaining value to the shareholder whenever the oil runs out.” Such “corporate suicide” is uncommon among “living” companies, however. Because their main purpose is their survival and the development of their potential, they would sooner shift the asset base than allow the current assets to determine the death of the institution.

Steering and Control from the Top

The long-term survivors shared two ways of handling a shift in their core business: the new business was not required to be relevant to the original business, and the diversifications were not initiated from a central control point. This pattern suggests that the companies’ managers were highly tolerant of “activities in the margin.”

Tolerance levels—toward new people, ideas, or practices—differ from company to company. Both a low-tolerance and a high-tolerance approach have a place in business, but which strategy a company should pursue depends on the amount of control that company has over its environment.

A management policy of low tolerance can be very efficient, but it needs two conditions to be fulfilled: the company should have some control over the world in which it is operating, and this world should be relatively stable. In such a world, a company can aim for maximum results with minimum resources. To achieve its goal of minimum resources, however, management will have to exercise not only some control over its surrounding world, but also a high degree of control over all internal operations. In these companies, little room exists for delegated authority and freedom of action.

A company may be lucky enough to live in a world that happens to be stable. However, any business that endures for more than a few score years will inevitably face changes in the external world. In a shifting and uncontrollable world, any company with the desire to survive over the long term would be ill advised to rely on a management policy of high internal and external controls. The Shell study showed that the survivors did, in fact, follow a high-tolerance strategy by creating the internal space and freedom to cope with external changes.

High tolerance is inefficient and wasteful of resources, but it enables a company to adapt to a changing environment over which the company has no control. Moreover, high tolerance provides a means for gradually renewing the business portfolio without having to resort to diversification by top-down “diktat.”

The spring ritual of pruning roses provides a good illustration of the different implications of a high-tolerance versus a low-tolerance strategy. If a gardener wants to have the largest and most glorious roses in the neighborhood, he or she will take a “low-tolerance” approach and prune hard—reducing each rose plant to one to three stems, each of which is in turn limited to two or three buds. Because the plant is forced to put all its available resources into its “core business,” it will likely produce some sizable, dazzling flowers by June.

However, if a severe night frost were to strike in late April or early May, the plant could well suffer serious damage to the limited number of shoots that remain. Worse, if the frost (or hungry deer, or a sudden invasion of green flies) is very serious, the gardener may not get any roses at all. In fact, he or she risks losing the main stems or even the entire plant.

Pruning hard is a dangerous policy in a volatile environment. If a gardener lives in an unpredictable climate, he or she may instead want to try a “high-tolerance” approach, leaving more stems on the plant and more buds per stem. This gardener may not grow the biggest roses in the neighborhood, but he or she will have increased the likelihood of producing roses not only this year, but also in future years.

Living companies, by contrast, are more like rivers. The river may swell or it may shrink, but it takes a long and severe drought for it to disappear altogether.

This policy of high tolerance offers yet another benefit—in companies as well as gardens. “Pruning long” achieves a gradual renewal of the “portfolio.” Leaving young, weaker shoots on the plant gives them the chance to grow and to strengthen, so that they can take over the task of the main shoots in a few years. Thus, a tolerant pruning policy achieves two ends: it makes it easier to cope with unexpected environmental changes, and it works toward a gradual restructuring of the plant.

Although this policy is not as efficient as hard pruning in its use of resources—since the marginal activities take resources away from the main stem—it is better suited to an unpredictable environment or one in which we have little control. And as the success of the long-term survivors indicates, diversifying by creating tolerance for activities in the margin has a better track record than diversification by dictum.

Creating and Shaping the Human Community

The way a company views its human community is the third area of distinction between economic companies and self-perpetuating organic companies. The fact that living companies want to survive far beyond the lifetime of any individual employee requires a different managerial attitude toward the shaping of its human community.

Economic companies are like puddles of rainwater—a collection of raindrops that have run together into a suitable hollow. From time to time, more drops are added, and from time to time (when the temperature heats up), the puddle starts to evaporate. But overall, puddles are relatively static. The drops stay in the same position most of the time, and some of the drops never seem to leave the puddle. In fact, the drops are the puddle.

“Living” companies, by contrast, are more like rivers. The river may swell or it may shrink, but it takes a long and severe drought for it to disappear altogether. Unlike a puddle, the drops of water that form the river change at every moment in time, and its activity is far more turbulent. The river lasts many times longer than the drops of water that shaped it originally.

A company can become more like a river by introducing “continuity rules”—personnel policies that ensure a regular influx of new human talent. Continuity rules also stipulate a fixed moment of retirement for every member, without exception. These strict exit rules remind the incumbent management that they are only one link in a chain. Within this expanded perspective, leadership becomes more like stewardship. A leader takes over from someone else, and eventually hands the enterprise over to yet another person. In the meantime, the current leader tries to keep the shop as healthy as he or she received it, if not a bit healthier than before.

Companies that are seen as teaming, living beings demand different thinking, not only about recruitment, but also about other aspects of human relations. This rethinking begins with a definition of self: Who are we? Who belongs to the institution, and whom shall we let in? Clarity on these points is essential for a living work community. Without it, there is no continuity. Without continuity, there is no basis for mutual trust between the community and its individual members. And without trust, there is no cohesion and therefore no community.

This thinking varies dramatically from the human-relations practices required in an economic company, where the HR function is expected to fit people to the asset base of the company. People are seen as cogs to fit a wheel, “hands” to serve the machines, or “brain? To make the right type of calculation or do the most promising research. Recruitment numbers are determined by the need for capacity to satisfy the foreseen demand for the company’s products. If the company has more demand than capacity to fulfill the demand, it adds new people and machines. When it has less demand, it reduces capacity by letting people go.

The type of people the company will admit or fire is defined mostly in terms of “skills”: “We need 250 metal bashers,” or “We have a surplus of paper pushers.” Within this framework, “people” are not hired or fired, only “skills” are. The mutual obligation between company and individual is that of “delivering a skill against the payment of a remuneration,” an agreement usually concluded under the umbrella of the country’s social legislation or some collective labor agreement.

In the living institution, criteria for admitting or dismissing people more closely parallels those methods used in clubs, trade unions, or professional bodies. Good care is taken that the new members carry the right professional qualifications, but the company also strives for a kind of harmony between the individual and the company. The members and the institution share certain values and purposes, and they aim to harmonize their respective long-term goals.

In the “living” company, admission is not determined solely by capacity. Capacity issues are addressed via the outside world, not by increasing or decreasing the internal membership. A shortage of capacity therefore leads to more subcontracting. In Italy, for example, Benetton does only a minor part of its manufacturing (recently, only 20%) with its own people. Benetton admits relatively few members to the inner core of its work community. In this case, the use of subcontractors has proven effective for acquiring capacity in a competitive industry with fluctuating demand.

The Choice

Many people in the business world may not want to create a living work community, and simply to manage a corporate machine with the sole purpose of earning a living. However, the latter choice has important consequences.

People in economic companies enjoy fewer options in their managerial practices. In those companies, only a small group of people qualify to be “one of us,” while the rest of the recruits become attachments to somebody else’s money machine. The company culture will consequently reflect this relationship. Non-managers will be viewed—and will view themselves—as “outsiders” hired for their skills rather than members with full rights and obligations. Their loyalty to the company will never extend beyond performing the tasks necessary to earn a paycheck. The lack of common goals and low levels of trust will require a strengthening of hierarchical controls in order to make the money machine work effectively and efficiently. As a result, the ability to mobilize all of the company’s human potential will be severely limited.

For such a company, a critical point comes when the succession of the inner community needs to be addressed. The absence of continuity rules or the reliance on the next generation of the family for corporate continuity will turn many of these money machines into “ships that pass in the night.” In short, economic companies not only face difficulties trying to operate effectively within a changing environment, but they also have to overcome considerable obstacles in their internal management practices just to make it to the next generation.

This paper was originally presented at the Royal Society of Arts in London on January 25. 1995.

Arie de Geus was appointed executive vice president at the Royal Dutch/Shell Group In 1978 and was with the company for 38 years. He served as head of an advisory group to the World Bank from 1990 to 1993, and is a visiting fellow at London Business School. Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen P. Lannon.

Further Resources: Many of the ideas in this article are discussed further In the video infrastructure and Its Impact on Organizational Success” by Me de Geus which is available through Pegasus Communications, Inc.