We judge others by what they do; we judge ourselves by our intentions.”

“What you do thunders so loud, I can’t hear what you say.”

These two quotations capture the difficulties inherent in trying to change an organization from one that is considered “ordinary” by today’s standards to one that strives to practice moral excellence. By “moral excellence,” I mean more than just avoiding what is illegal, or simply conforming to contemporary ethical standards. Instead, I mean embracing age-old moral truths and pursuing their practice with the same vigor and commitment with which we strive toward technological, marketing, or financial success.

Why make such an investment in moral excellence? Because moral excellence drives human energy. Human energy—in the form of initiative, creativity, fortitude, and stamina—drives product and service excellence, which, in turn, enhances financial performance. In my estimation, the pursuit of moral excellence is the most effective and enduring way to energize organizations, because it taps into our noblest aspirations. In addition, it can engender a social ecology in our companies that fosters individual maturation and happiness:

A Difficult Journey

Most employees want to be moral, and they prefer to spend their working lives in moral environments. Similarly, most leaders, including the members of the board of directors and CEO, want their organizations to be moral. Then why is it so difficult to transform an organizational culture to one based on moral excellence? I believe there are three reasons.

First, after decades of being treated as a herd of “hired hands,” employees are highly skeptical of new schemes of governance. They say to themselves, “I hear what management says, but do they mean it? Will they personally practice what they preach?”

Second, most corporations have not undertaken major efforts to develop the philosophical and moral underpinnings of their governance systems. Most are based on a hodge-podge of notions derived, in part, from Roman army ideas about control, technological innovations aimed at maximizing efficiency, scientific principles about measurements, and lately some accommodations to Douglas McGregor’s Theory Y. Few corporations have actually made a systematic effort to design their methods of governance in congruence with how human nature has evolved and is evolving.

Third, most managers have received minimal, if any, instruction about the moral dimension of exercising their responsibilities. Moral excellence in an organization must be undergirded by a network of managers who have paid attention to their own formation as human beings, a subject seldom found in the curriculum of our corporate management education programs or business schools.

Building a Culture to foster Moral Excellence

So how does one begin the arduous task of retrofitting a corporation’s culture to introduce the pursuit of moral excellence at its core? I believe we should begin by taking an honest look at our routine business activities (see “The Moral Stepladder”). To what degree do actions, intended to maximize self-interest, interfere with the company’s overall interest? Are decisions influenced by political connivance? Does bureaucracy overwhelm individual responsibility? Do rules and procedures take precedence over human judgment, even when the application of the rule to a particular situation is counterproductive or unjust?

Morality is either facilitated or hindered by the environment. People who may be moral at home are often less moral at work because only the most courageous of us can step out of roles and expectations when it feels like everyone else is “selling out.” The journey toward moral excellence entails an ongoing ratcheting up of personal moral formation in tandem with creating a culture that supports and expects such practices. I believe that transforming the moral ecology of a corporation entails two broad-gauge strategies: (1) establishing moral principles for human relations in a company, much as financial information is based on accounting principles; and (2) encouraging managers to pursue their personal moral formation with the same vitality with which they develop professional skills.

Guiding Principles

To identify central organizing principles for human behavior, we can rely on much wisdom that has been collected and tested over the centuries. From my experience as a business practitioner, I would suggest four basic guiding values: localness, merit, openness, and leanness.

Localness is a philosophy that guides the conduct of relations between different levels in an organization. It is more than just decentralization—it is about liberating employees from the oppressive features of the command-and-control structure so that each individual may use his or her job to stretch his or her talents in ways that also benefit the organization. Localness disperses power to competent people in an orderly, disciplined way. Over the brig term, wisely distributed power produces better economic results than lees centralized power.

Merit means directing ever: decision and action toward the organization’s goals and aspirations, while being consistent with the company’s other values. In practice, merit helps to cure the office politics and proliferation of bureaucracy that can demean the dignity of people engaged in work.

Openness and honesty are the world’s best navigational instruments. These qualities enable an institution or individual to take stock of where they are, and to chart a course for where they want to go.

Leanness tempers the human inclination for excess comfort and expansion, so that an organization or individual will maintain its health in both good and poor economic times. It embeds the ancient virtue of thrift into the soul of the corporation.

The Moral Stepladder

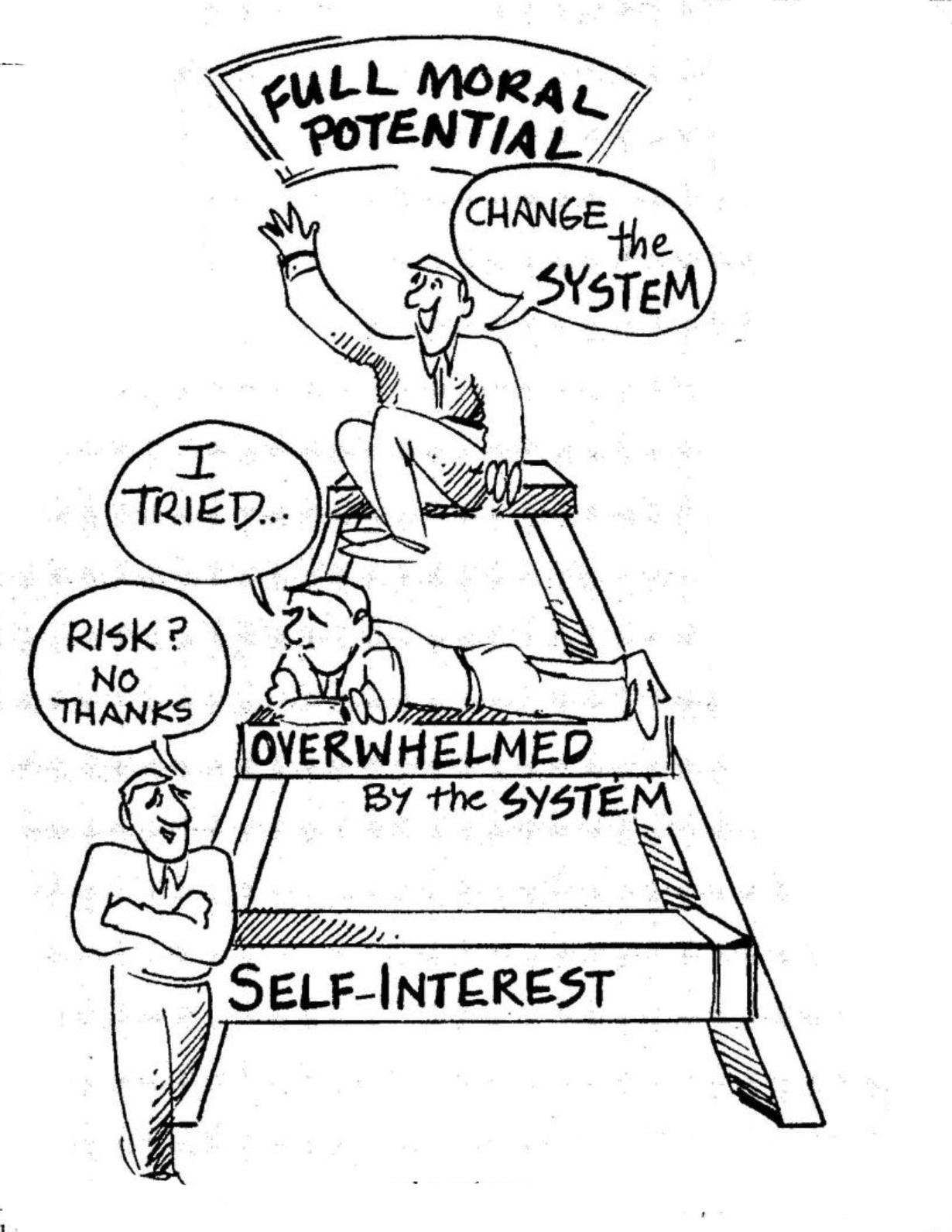

For instance, suppose an employee suggests to his or her manager that a certain standard procedure is wasteful and might be performed more economically by a proposed change. However, the manager believes that such a change would be unpopular with the head of another department, who, in turn, would lobby against it with his boss, so he decides to ignore it. In other words, he puts self-interest ahead of common interest and risk avoidance ahead of his personal responsibility.

The scenario I have described represents behavior on a low rung of our moral stepladder. Nothing done was illegal, nor can anyone point with evidence to a lie. If it were questioned, it would no doubt be excused as something that fell between the cracks. But repeated acts like this sap the vitality of worker teams, stunt the growth of individual aspirations, and tarnish the souls of corporations. They also damage the financial performance of the organization, because it is impossible for dispirited people to thrust themselves fully into productive action for the benefit of an organization of which they are — whether they admit it to themselves or not — ashamed. I label this rung of our moral stepladder, “Putting Self-Interest First.”

If we look at the same scenario on the next rung of our moral stepladder, our manager evaluates the employee’s suggestion on the basis of how it will affect quality and cost, is not influenced by self-interest or politics, and recommends that it be introduced into operations. His idea may be adopted, but more likely, his original fears were accurate and the suggestion is vetoed for political reasons. He informs the employee who originally made the suggestion and expresses appreciation for his thought and effort. We label this rung, “A Moral Effort Overwhelmed by the System.”

The highest rung on our ladder belongs to the manager whose sense of personal responsibility is strong. He attempts to-change “the system” from one based on politics to one based on merit. How might he go about this? He could commit himself to adopting the highest rung on the ladder as his personal standard for his area of responsibility. He could then set expectations for his staff that all departmental decisions be executed at the higher step of the ladder. After an example is set in his own department, which no doubt others will notice, he can credibly advocate for change in the larger entity. We might call this step on our moral stepladder, “Marching to My Full Moral Potential (without becoming a fanatic or martyr).”

This simple and fictitious story offers a scale for comparing the relative character of moral action from a low-level approach to an admirable effort. Thinking of moral action in terms of a progression (i.e., using a stepladder) gets people in an organization out of the either/or trap of “It’s not immoral, so it’s OK.”

Another foundational principle, which I believe underlies the four values stated above, is love. I am not referring here to the romantic or familial connotations of the word, but to “love” in its most universal meaning: extending one’s self toward helping another person to become complete. In this sense, love is a predisposition toward helping our employees, customers, vendors, owners, or other constituents. It is an attitude that we can cultivate and direct by our will, just as we do with other personality characteristics. The central question to ask oneself in putting the value of love into practice in the workplace is, “What can I do to help Joe or Mary (or ten thousand employees) complete themselves more fully as human beings?’

Practicing the value of love in business is not a soft undertaking, nor is it without tension. The loving manager is always faced with the pressure of achieving the business imperative—balancing the common good of the organization with the needs of the individual. Oftentimes, rendering that help requires inflicting short-term hurt, such as telling someone things he or she would rather not hear. Have no illusions—delivering or receiving this kind of message is not fun. But when it is done for the purpose of assisting in growth, it is a loving act. And if it is genuinely intended, it will be heard and appreciated, even when it hurts. If a loving manager is quick and tough in addressing issues when they surface, most damaging organizational issues can be kept at a minimal level.

Moral Formation of Managers

In order to embed these guiding principles in our workplace, we must cultivate value-based relationships, particularly between individuals at different echelons. This leads us to the second aspect of creating a culture based on moral excellence: promoting the moral development of managers. Those who have highest operating responsibility in an organization should have an equal responsibility for their own moral formation. I believe that when a company engages a manager in a leadership position, his character is as important a consideration as his professional competency.

The emphasis on the importance of promoting the moral formation of mangers is not meant to imply that the majority of managers are immoral. That has not been my experience in more than 35 years in corporate life. But I do believe that most managers operate in a system where morality is underdeveloped in relation to professional skills in technology, finance, communications, etc. Many managers do not achieve the excellence they are capable of, simply because they have not devoted enough time to reflecting on the application of the wisdom of the ages to their professional responsibilities.

Leaders who intend to build corporations that tap into the full inner resources of their people must pay as much attention to their own moral formation and that of their key managers as they do to mental and technical proficiency. As an individual assumes more responsibility in the organization, moral formation becomes even more important. The depth of commitment that employees make to the company’s well-being is directly related to their perception of the moral formation of their boss and their boss’s bosses. The same can be said to a lesser degree about a customer’s loyalty to a supplier.

When a board of directors removes a CEO because the company doesn’t respond to his direction, or when a leader loses his position of power because his followers reject him (as happened to Richard Nixon), those who have known the deposed individual frequently say, “Success didn’t change him. It unmasked him.”

Behind that comment is the tacit belief that the individual had some chinks in his character all along, but he was still able perform his responsibilities competently and move on to even higher levels in the company. But what are minor cracks in moral formation in upper middle management positions can be fatal flaws in senior managers, because they set the moral tone for the organization as a whole. This is a critical point that is often underestimated by those with the responsibility for anointing senior executives or CEOs and by those preparing themselves for higher responsibility.

Leadership Qualities

Creating a culture based on moral excellence requires a commitment among managers to embody and develop two qualities in their leadership: virtue and wisdom. The dictionary defines virtue as “moral excellence; right living; goodness.” Virtue comes from the Latin word virtus, which means “manliness,” or “virility.” Yet, in modem management circles, virtue is often associated with notions of softness and weakness. Let there be no doubt, transforming corporate rat races into morally uplifting cultures that earn superior financial returns requires an inner toughness on the part of leaders—a willingness to stand against the crowd, an ability to question well-rationalized assumptions, and a faith in the power of the human spirit.

Wisdom, in turn, is more than intelligence. It suggests a special quality of judgment in human affairs, based on knowledge of moral principles, human nature, human needs, and human values. Wisdom is more than what people know, it is who they have become; and who they have become is determined by how congruent their behavior is with their knowledge.

Getting from Here to There

Creating a values-based organization is a formidable undertaking. This is true whether you are the CEO of a complex corporation with 100,000 employees or the manager of a small, autonomous division. It is a lifetime’s work, and with each step forward, there are new obstacles to overcome and new risks to be taken. Just as your organization reaches one plateau, a new mountain will emerge on the horizon.

It took Jack Adam (my predecessor as CEO at Hanover) and myself six years to see the link between the changes we made in our governance structure and the improved economic performance that followed. It took us an additional six years to build what we considered a mature, values-based, vision-driven culture — meaning our experiment in corporate governance reached a point where it produced consistently superior financial results and widely recognizable individual growth through a process that we knew how to replicate.

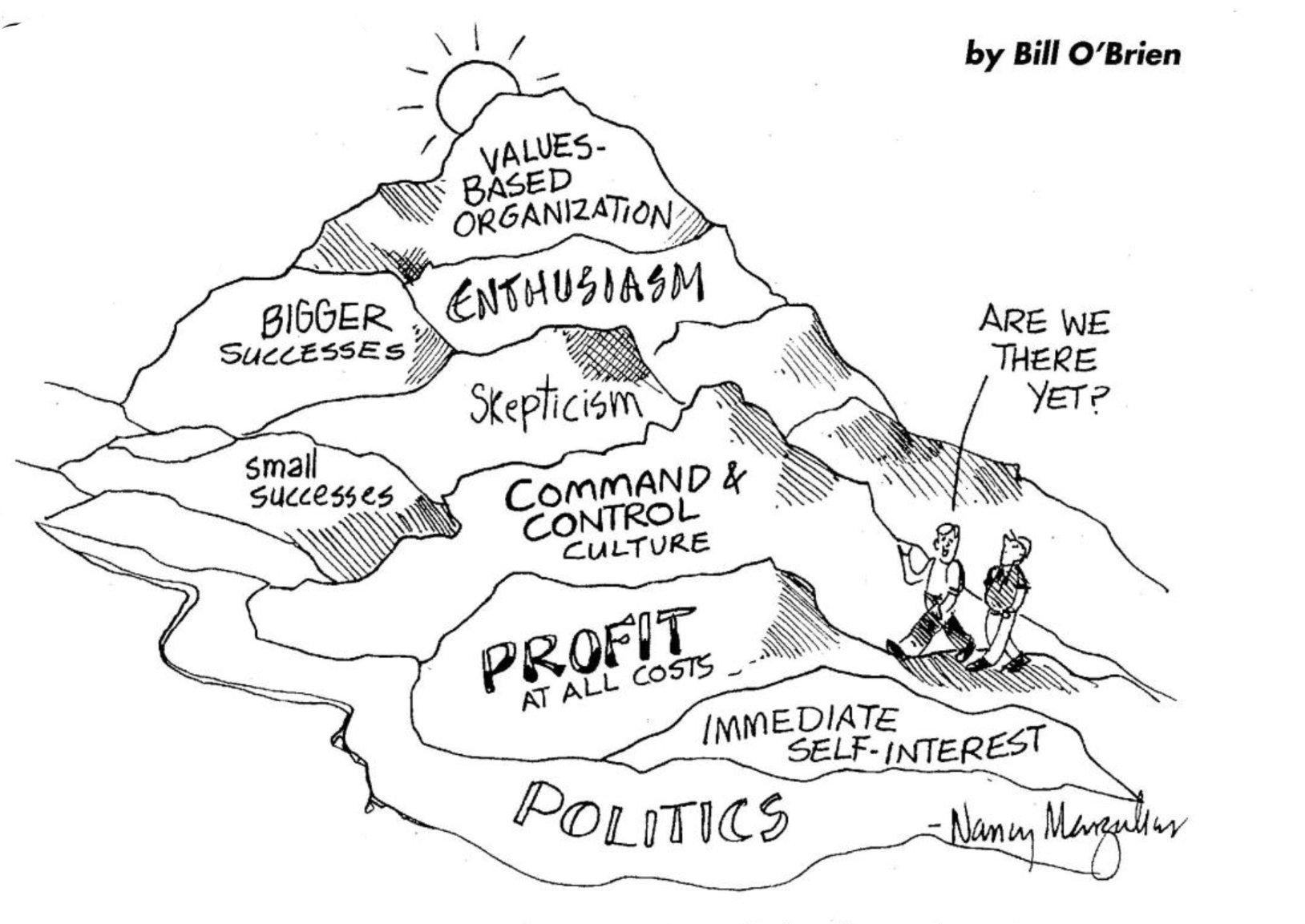

Why does it take so long? Because in order to bring about such a transformation, management has to change some of its long-held mental models and replace long-standing habits (see “Challenging Our Mental Models”). People quickly grasp the intellectual dimension of these ideas, and the over-whelming majority, in my experience, conceptually agree with them. But internalizing the ideas and translating them into practice takes quite a bit longer. There needs to be debate and discussion, as individuals wrestle with the personal implications of the new ideas. These conversations will then be followed by the application of the concepts to authentic situations.

Take a Look Inside

Embedding a new philosophy in an organization consists of a series of small successes, followed by bigger successes. All the while, management must live up to the philosophy — in both good times as well as times of crisis. In other words, people must see that the new philosophy works better than the culture being phased out, and also see that their manager is “walking the talk.” While this progress is taking place, there will be periods of skepticism and times of enthusiasm, periods of doubt and times of confidence.

Ultimately, the quest for organizational transformation must begin with a personal commitment within each individual to pursue moral excellence. Pushing for the transformation of an organization’s culture entails risk, and we can only face that risk if we are clear about our convictions and the beliefs we want to live by. It comes back to Ghandi’s observation that transformation takes place when you “become the change that you wish to see in the world.”

Although this type of cultural change will take time, the potential pay-off is immense. The benefits of releasing bottled-up human energy through the pursuit of moral excellence will show up in a tremendous increase in productivity, as well as unimagined improvements in relationships with external constituencies, who will respond positively to the quality of the experiences they have with such an organization.

It has been my experience that when people are free to choose between high-quality ideas or inferior ones, they inevitably choose the former. They deserve to have this choice in our corporations.

This article is an edited version of B. O’Brien. “Moral Formation for Managers: Closing the Gap Between Intention and Practice” (Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Organizational Learning Research Monograph, 1995). Copyright 1995 by Bill O’Brien. Bill O’Brien was the chief executive officer of Hanover Insurance Company until his retirement in 1991. During his 21-year tenure at Hanover, Bill coauthored a business philosophy that resulted in a significant corporate turnaround. By applying the concepts of organizational learning, he and his staff created one of the most respected companies in the insurance industry, both in terms of the work environment and its profitability. Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen Lannon.