The book The Day the Universe Changed tells of a man who once commented to the philosopher Wittgenstein that medieval Europeans must have been foolish to believe that the sun revolved around the earth. Wittgenstein reportedly responded, “I agree. But I wonder what it would have looked like if the sun had been circling the earth.” (James Burke, The Day the Universe Changed, Little, Brown St Co., 1987)

Of course, the observations would be exactly the same. This is precisely the dilemma that occurs in a “Growth and Underinvestment” structure: how can you tell whether your customers are defecting because of actions you are taking, or simply because of the “natural” dynamics of the product lifecycle?

A Dying Product Line

A manager in a Fortune 500 consumer products company (CPC) once told a story about a product they had decided to discontinue. They felt that its projected future market potential was not worth further investment. In fact, they were convinced the product was entering its dying stages, so they decided to hasten the inevitable by shutting the plant down.

At the same time, however, they were just beginning a strategic alliance with a Japanese manufacturer who wanted to take over the product line. As a gesture of good will, CPC agreed to license the product — on the condition that they would not renew the license if the Japanese firm was unable to sell at least 5000 units per year. Much to their surprise, the Japanese firm sold over 15,000 units in the first year alone.

It was the same product, manufactured at the same plant, which was operated by the same people. How, then, was the Japanese firm able to produce results CPC could not even imagine, let alone achieve? The answer lies, in part, in understanding the dynamics of the “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype.

Growth and Underinvestment

The “Growth and Underinvestment” structure is a special case of the “Limits to Success” archetype (see “Growth and Underinvestment: Is Your Company Playing with a Wooden Racket?” Vol. 3, No. 5). The storyline of the archetype can be described as follows: A company experiences a growth in demand that begins to outstrip the firm’s capacity. When the capacity shortfall persists, the company’s performance (such as on-time delivery) suffers and demand decreases. The fall in demand, however, is then seen as a reason for not making future investments in capacity, rather than a symptom of past underinvestments. This leads to a self-fulfilling cycle of continued underinvestment and falling demand. In the end, the decision to shut down production, as in CPC’s case, may seem the only appropriate action.

How, then, can an organization avoid doing something that it cannot even see? As in the case of the earth-centered view of the universe, we need a theory that provides us with a different interpretation of the same observations. The following seven-step process can help us use the “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype to better assess investment choices.

1. Identify Interlocked Patterns of Behavior

Ancient astronomers studied the movement of the sun and related its orbiting patterns to the changing seasons. Similarly, to recognize a “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype, we need to identify relevant patterns that appear to be interconnected — such as capacity investment decisions with customer orders or performance measures (e.g. de-livery delay). If there appears to be a systematic correlation, it may be an indication that the two are causally linked.

2. Identify Perceptual Delays

A critical step in analyzing how investment decisions are made is identifying the delay between the time when performance falls (e.g. deteriorating service quality) and when additional capacity actually comes on line. A significant source of that delay is in perceiving the declining performance (see “Underinvesting in Service Capacity”). Questions such as “How fast do we believe we should respond to falling performance measures?” or “What are the internal ‘hurdles’ that a product must pass?” can help surface mental models that may be blinding the organization to the need to invest.

3. Quantify and Minimize Acquisition Delays

In order to identify acquisition delays, you need to have a clear idea of the procedures and people that will be involved in the process of deciding and acquiring the additional capacity. Quantifying those delays requires a thorough understanding of how the whole process actually operates — not the just way it is “supposed” to work.

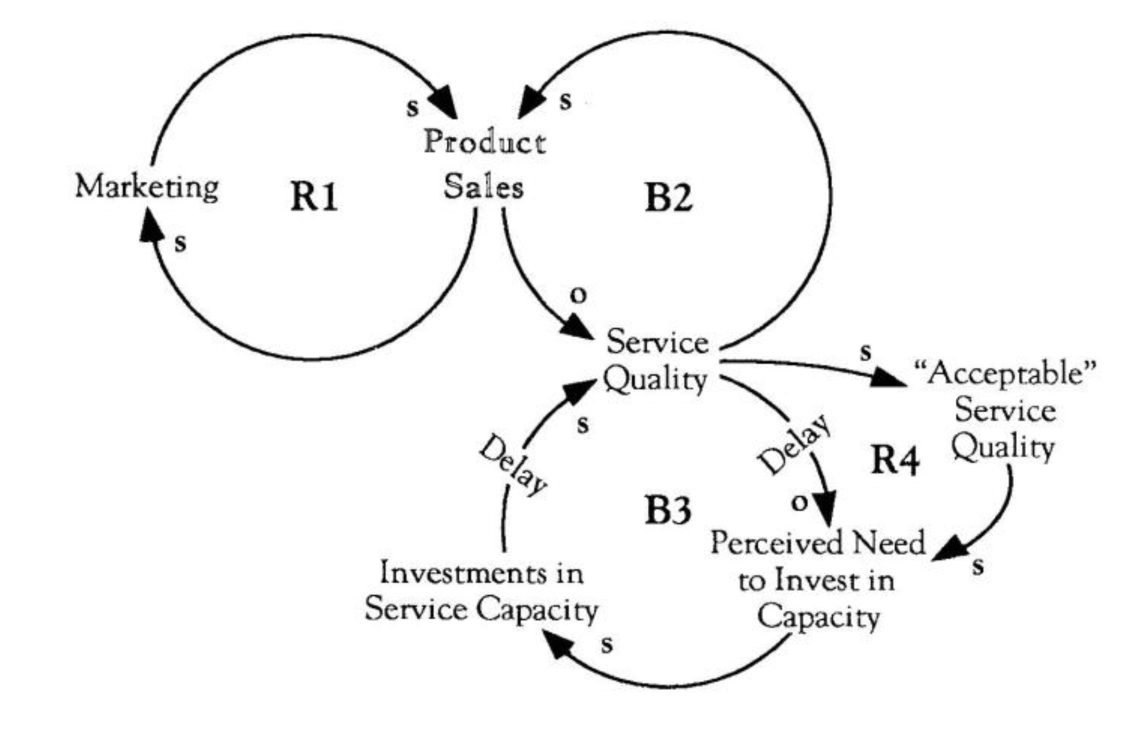

Minimizing both the perceptual and acquisition delays is important because if the time delay in adding capacity is too long, the performance measure will continue to deteriorate until product sales falls off. When sales fall, it alleviates the pressure on the performance measure (B2) which, in turn, can send a signal that further investments are not necessary (B3). The lack of investment pushes the two balancing loops into a figure-8 cycle that becomes a vicious reinforcing spiral of deteriorating quality and lower demand. Although the decreasing product sales are a result of the company’s inaction, it looks as though the customers have made a unilateral decision not to buy the product.

4. Identify Related Capacity Shortfalls

Expanding capacity for a product often entails further investments in many areas to develop support mechanisms and infrastructures. Expanding service capacity, for example, may lead to increased sales that will outstrip capacity somewhere else. If other parts of the system are too sluggish to capitalize on the added capacity, the customers may still view the company as providing poor service. Demand will then drop, thus kicking off the figure-8 dynamic described above.

5. Check for Eroding Performance Standards

To what extent are current investment decisions based on standards derived from past performance? For example, a 50-hour work week or a 3-month backlog may be the currently accepted signals that trigger additional investments, but the signal to expand may seldom come because of the demand-dampening effect that results when we wait too long to invest. An additional danger lies in the existence of a link between current performance levels and the performance standard, because it can also create a reinforcing cycle of eroding standards that leads to underinvestment and further erosion (R4).

Underinvesting in Service Capacity

6. Avoid Self•Fulfilling Prophecies

As in CPC’s case, we need to ultimately question the deep set of assumptions that drive our capacity investment decisions. The BCG Growth-Share matrix is an example of a framework for making strategic investment decisions that can lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Through rigorous analysis based on a set of assumptions, the process produces categories — question marks, stars, cash cows, and dogs — which guide investment decisions. Problems arise when the labels outlive the relevancy of the analysis and simply become self-sustaining prophecies, i.e., you believe that a product is a “dog,” therefore you underinvest in it, and it stays a dog. Avoiding that danger requires going back and challenging the basic assumptions about the product, which includes reevaluating both the product and the market.

7. Search for Diverse Inputs

Challenging basic assumptions requires having multiple viewpoints which can move the discussion beyond current understanding. When making investment decisions, try to involve people who have a new perspective on issues such as who the customers are and what they see as the benefits of the product. This may help you break out of the box of current thinking, which is particularly important if you arc contemplating abandoning a product.

Encouraging “Intrapreneurs’

The real message of the “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype is that investment decisions should be made from a fresh perspective each time. Instead of relying on past performance or past decisions, try playing “intrapreneur” and look at the process as if you are introducing a brand new product. This may provide the necessary perspective to see new life where others see only a dead product.

Note: The “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype is a special variant of the “Limits to Success” archetype. It is difficult to illustrate with general examples because it requires specific detailed information about how investment decisions are made within companies. For additional help in using this archetype, see “Using ‘Limits to Success’ as a Planning Tool,” Vol. 4, No. 2.