The pendulum that is the Boston real estate market is on the downswing. Suburban developers have been particularly stung by the recent downturn since most of the recent construction was concentrated outside the city. Would the developers have encountered the same fate if they had more information about the market’s health? That was the question asked in a Boston Globe article entitled “More Market Data May Have Saved Some Developers” (February 25, 1990).

Rapid suburban development was a result of the need for new revenues in financially strapped cities, according to the article. Since Proposition 2-1/2 imposed limits on tax increases, cities have competed heavily for new development to increase their tax base.

To prevent another real estate crisis, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) wants to open a data bank for suburban developers and planners. It would provide information on vacancy rates, thereby helping them time construction to meet market demand. The theory is that more market data would prevent developers from overbuilding and creating another glut of commercial space.

The role model for the MAPC data bank is the system developed by the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) in 1984. The BRA publishes quarterly reports of office vacancy rates based on staff research and information obtained by builders, building owners and real estate brokers. The BRA exercises further market control through its design review process, which can speed up or slow down approval for new projects as necessary. Because of the BRA’s control over project approval, developers have an incentive to cooperate and provide the BRA with the necessary information.

One potential problem for the MAPC project is that the data bank would require developers to supply information on new projects to the MAPC. In an industry where information is often the key to competitive success, such a cooperative venture might break down in a highly competitive market, just when such information would be most crucial for predicting and preventing overdevelopment. Even if developers had access to market data, there is no guarantee that they would adapt their long-term plans accordingly. Many developers believe their own project will succeed despite the market outlook.

Discussion Questions

- A “boom and bust” phenomena like the one that Boston developers experienced usually signals a negative feedback loop with delays at work. Can you trace out at least one loop that might be producing such behavior?

- Based on the loop(s) you drew above, do you think more information would have saved some developers, as the Globe article suggests?

- What was the driving force behind the overbuilding in the suburbs?

- What sort of city intervention would significantly help developers avoid a future cycle of overbuilding?

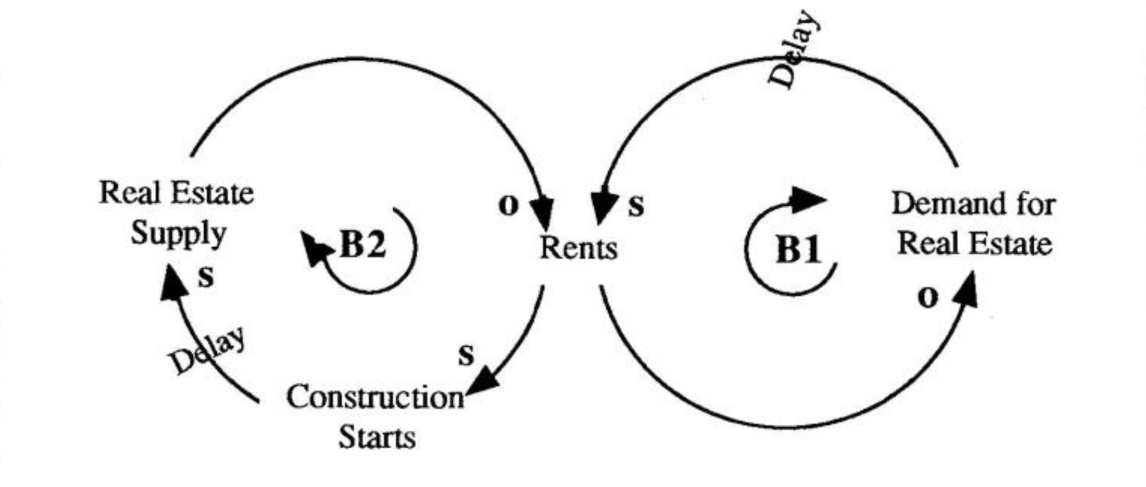

The Boston real estate market, like any other sector of a free market economy, is subject to the laws of supply and demand (See Toolbox, page 5). As demand for real estate increases and supply remains fixed — which usually happens in the short run — rents begin to rise. If they rise too high, they eventually bring down demand because the rent becomes unaffordable for some people.

Of course there is a supply side to this story. Rising rents increase the attractiveness of real estate and encourage more development. After an appropriate planning and approval delay, new construction begins and, after a construction delay, real estate supply eventually expands. But as new units come into the market and compete for tenants and buyers, rents begin to fall. Together, the supply and demand loops attempt to keep the real estate market in balance.

If all the delays — planning, approval, and construction — were short, perhaps on the order of weeks, then supply would adjust more rapidly and rents would not fluctuate as much.

The market would approach equilibrium, and there would be little discrepancy between supply and demand. In real life, unfortunately, supply adjustments take a long time while demand adjustments can be quick and brutal, as they have been during the latest downturn in Boston real estate.

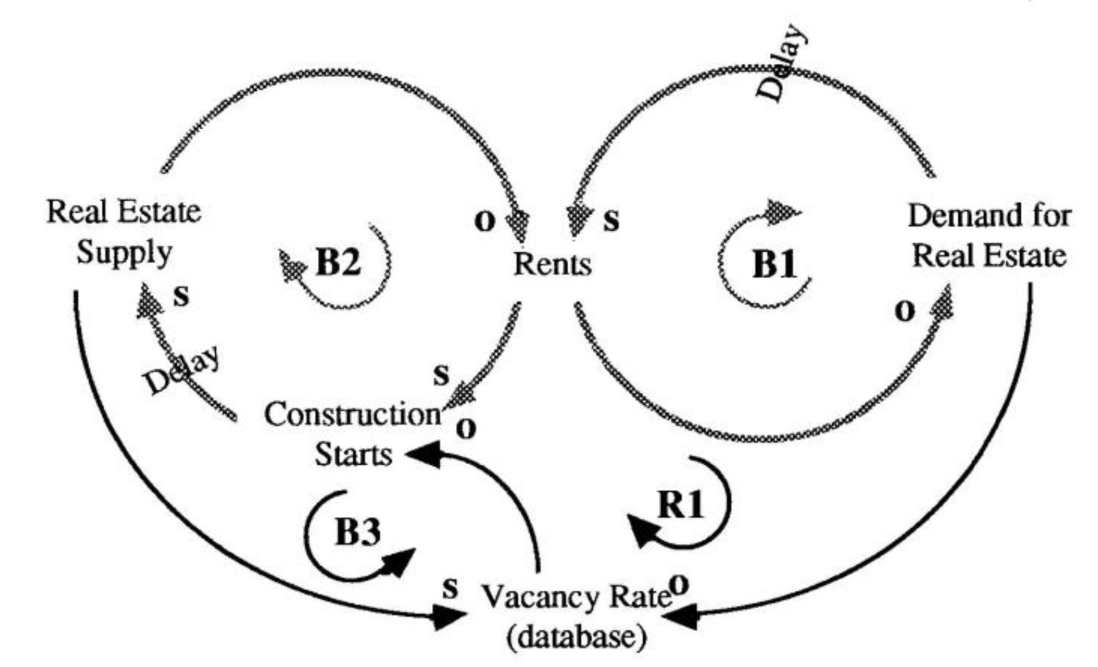

In the Boston suburbs throughout the eighties, demand remained high and bid the rents to such heights that it drove developers into a “building frenzy.” Due to the delays in the system and poor market information, massive overbuilding occurred. Each developer continued to think his or her development would be the first or the best in the market.

By establishing a real estate data bank, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) hopes to prevent another “boom and bust” cycle by providing developers and planners with an accurate and early warning signal of market saturation. Overbuilding would be signaled by a rise in vacancy rates while a decrease in vacancy rates would indicate an impending space crunch. In theory, providing accurate information on vacancy rates would slow down construction by creating a new balancing loop: as developers saw vacancy rates rising, they would slow down or stop new construction and thus prevent overbuilding.

The success of the MAPC data bank program depends on at least two things: the accuracy of the information on supply and demand, and the credibility it has to affect developers’ decisions. If developers decide to build even though vacancy rates are on the rise, the balancing process will not work.

The reason why the BRA is reasonably successful at regulating development is that it exercises considerable control over the planning and approval process. This ensures that developers will cooperate and provide the BRA with accurate information. It also guarantees that developers will not be allowed to ignore market signals and build anyway. Without a regulatory component similar to the BRA, the MAPC would face considerable obstacles in trying to gain cooperation and credibility among developers.

The MAPC would face further difficulties if it tries to regulate development. Unlike the BRA, which only oversees Boston development, the MAPC needs the cooperation the suburban communities-101 “little fiefdoms,” as they have been called. With many of these communities feeling tremendous budget pressures, getting and maintaining an agreement may prove to be the toughest task. Armed with better information, some communities might try to entice more development for themselves by offering special incentives. The result could be a bidding war among the communities that would encourage even more development.

For the MAPC project to be effective, all the surrounding communities would have to agree to coordinate development efforts rather than compete for them. By itself, the MAPC data bank will not change the structural forces that are responsible for over-building — namely, the inherent delays in the system that cause rents to rise and remain high enough to entice developers to grab a “profit opportunity” and the other pressures in the system (such as taxes) that make new developments attractive. Without greater consideration of the structural dynamics of supply and demand in the real estate market, providing more data to developers would be a questionable “quick fix” solution. Further reading: “Texas in the Northeast?” Forbes, April 2. 1990 and “US property collapse could drag down world’s markets,” Sunday Morning Post, February 18, 1990.