Being a systems thinker means seeing opportunity everywhere. Systems thinkers know that teams, organizations, and societies can multiply their positive impact by reducing delays, friction, waste, and unintended consequences.

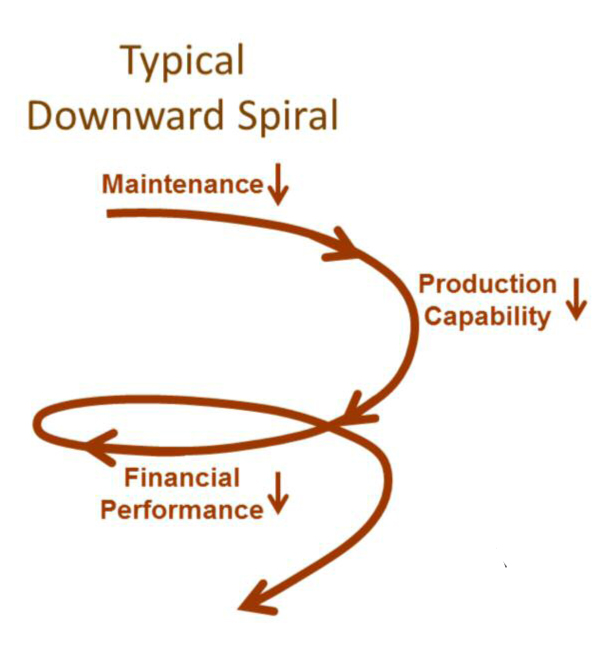

Yet all too often, we find ourselves working in systems stuck in downward spirals of self-defeating dynamics. Intuitively, we all know the story of the downward spiral. A sports team makes a few mistakes and then cannot manage even the most basic play. A company cuts maintenance budgets due to financial pressure, which results in more breakdowns and lower quality, rising costs and lost customers, and eventually even greater financial pressure.

The downward spiral is a metaphor for decline, a self-reinforcing process that depletes something of value (or, in systems thinking terms, a “stock”). It can be described as a cycle of disinvestment or deterioration, as players withdraw resources from a system, an action that reduces its performance and prompts further withdrawals down the line. Unfortunately, when we are part of a downward spiral, we almost always find it difficult to see a way out because the incentives in the situation often reward narrow, short-term thinking.

Mobilizing change in a downward spiral means starting without the usual conditions for success. Because of the financial and emotional stress of the situation, we are unlikely to have accurate data, sufficient resources or time, committed participation from other stakeholders, or executive sponsorship. We lack the inclination to collaborate with others because our trust has eroded. And, frankly, why should we invest more effort before “they” fix their part of the problem?

TEAM TIP

When looking to reverse a downward spiral, begin by identifying what is limiting key players’ willingness and ability to work on the system — trust, time, awareness, etc. How can you grow more of that enabling resource?

For example, a colleague told me about a company where two department leaders who reported to the same boss were competing to avoid the boss’s disapproval. As a result, the leaders distanced themselves from each other. They were cordial in group settings, but otherwise they hardly spoke. They would only return each other’s emails or phone calls when absolutely necessary. This dynamic left the staff in the leaders’ departments unclear how to manage interactions, as their policies conflicted with each other. As a result, the company paid more contract penalties, and service quality suffered. Of course, overall results worsened, and staff confusion increased. But when my colleague asked the two leaders about addressing the issue, they said they wanted to send their teams to a workshop on collaboration.

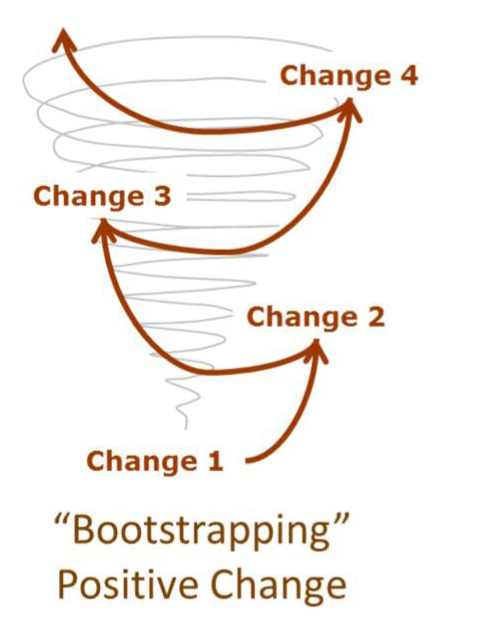

Systems thinkers believe that if people have a shared picture of how a system works, they can shift things for the better. Our “meta-model” for change is that systems thinking will lead to shared vision, common mental models, and coordinated action on the leverage points that will turn the situation around. Unfortunately, in a downward spiral, where we most need systemic change, we typically cannot negotiate the time or attention to fully understand key dynamics and coordinate action. What we need instead is a meta-model that lets us “bootstrap” our way out of the downward spiral.

“Bootstrapping” is short for “pulling up by one’s bootstraps” or self-generated change. For example, we refer to a computer as “booting up” because it is hardwired to execute a small amount of code that instructs it to execute the next batch of code and so on, repeating until the computer is ready for use. In similar ways in other systems, the dynamics of organic growth — including feedback, accumulation, and amplification — can over time turn small changes into the miraculous forms of a baby, a town, a business, an economy, or a complex ecosystem.

Rediscovering Organic Growth

Given the choice, most leaders want to grow something real. Much as they welcome change, they lose all motivation when asked to “go through the motions” of improvement. “I just can’t do fake stuff,” said a senior vice president. Though they may compromise to reach short-term targets, most would prefer to focus on long-term, ongoing results and real value.

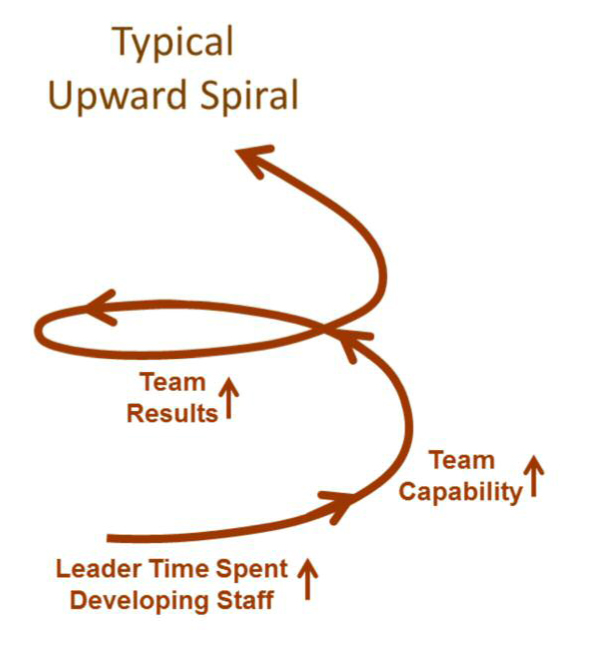

Of course, we do not “grow” results directly. The only way to improve long-term financial results and other outcomes is to grow the systems and capabilities that generate them. This is why nearly every systemic change is ultimately about fostering organic growth.

Whereas inorganic growth occurs through accretion — as when a business grows through mergers – to grow organically means to increase (or restore) through natural development, measured in size, complexity, or maturity. Any system that is growing organically is functioning well enough to create a surplus that can be reinvested in new capabilities or provide resources to the larger system. One of the most inspiring aspects of these turbulent times is that there are signs that those who really know how to grow or regenerate an organization can differentiate themselves for the future. Witness the performance of what Jim Collins and Morten Hansen refer to as “10x companies” in a recent study (Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos and Luck – Why Some Thrive Despite Them All, HarperCollins, 2011).

Yet for most leaders, the dynamics of organic growth are invisible day to day. They cannot see whether their core capabilities are growing, deteriorating, or getting close to a tipping point. Managers see financial results and other outcome metrics, but the system that generates those results is a black box, and everyone in the organization has to discover for themselves how it works. Ironically, this sometimes leads busy leaders to think more simplistically, just when they need to be thinking more systemically.

Still, in most cases, asking leaders to learn the language of systems thinking so they can discuss growth is too high a hurdle. They need a simpler lens to prompt them to ask the right questions and make good decisions. Is there a way to help leaders see and manage the dynamics of organic growth more intuitively — without requiring them to learn a new language before they can start?

The Upward Spiral

In almost every culture, the shape associated with growth is the spiral (as shown by Angeles Arrien in Signs of Life: The Five Universal Shapes and How to Use Them, Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1998). Many things in nature grow in spirals, from ferns to seashells to whirlpools. They can be as small as the double helix of a protein molecule and as large as the spiral arms of the Milky Way. Over 80 percent of plant life exhibits spiral growth patterns (see SpiralZoom).

The spiral is simply the shape created by a self-reinforcing growth process. By definition, a spiral winds around a center, in a progressive expansion or contraction, a rise or fall. What we see is the accumulation of changes as the system iterates over time. We tend to associate an upward spiral with growth, development, and evolution, as reflected in the architecture of spires and towers. Thus, I have begun using the metaphor of the upward spiral as a meta-model for systemic change. I define the upward spiral in this context as a metaphor for growth or “mutually reinforcing change that creates or regenerates something we value.”

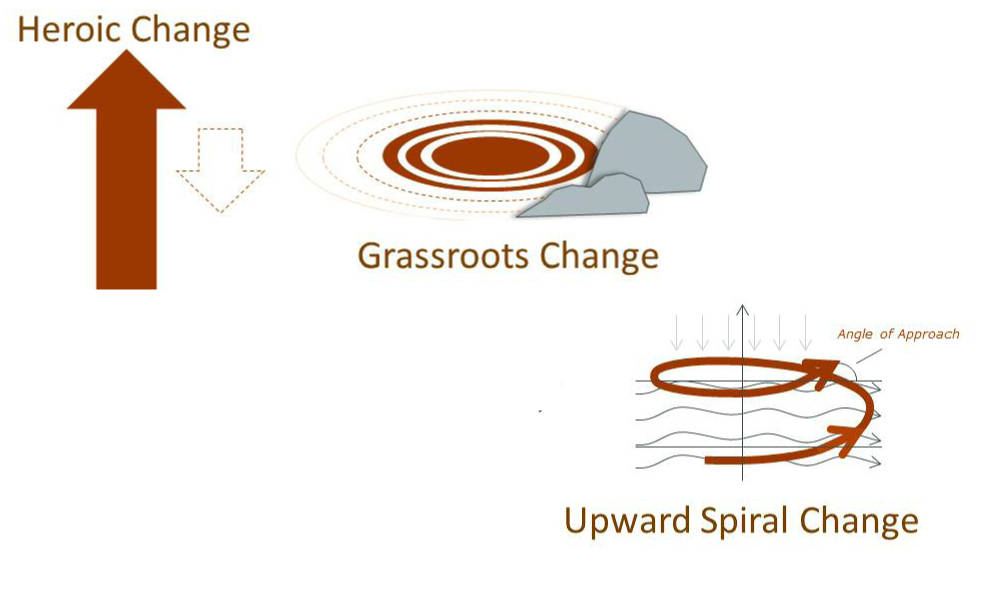

To understand why the upward spiral metaphor simplifies and empowers how we think about systemic change, let’s take a look at two other prototypical models, Heroic Change and Grassroots Change.

With Heroic Change, change is likened to a journey or “trip to the moon.” In practice, it generally involves a strategic injection of resources and energy to orchestrate a “trip” from the old way to the new way. The drawback is that it is resource intensive, so we may find we do not have enough fuel to get to our destination. If we have not reached our goal and have bulldozed past opposition, the system may swing back toward the other pole, stuck in oscillation rather than advancing (see The Structure of Things by Robert Fritz).

By contrast, with Grassroots Change, we think of change occurring through “ripple effects.” It relies on many small-scale efforts, gradually winning converts until the new way replaces the old. This approach allows for creative emergence, yet can fail to take off if it does not engage structural barriers that limit progress or if local efforts do not build on each other. If our experiments run out of energy, or if we have excluded important opposition, the system can swing back again toward the other pole.

As an alternative, the upward spiral metaphor prompts us to engage limits and opposition, but at a manageable angle. It is not straight up, nor is it entirely sideways. Like a spiral staircase, it grows an asset stepwise, in increments that fit with our resources at any given time. This does not mean we lower our sights; it simply means we only go as fast as we can go and keep it real. The upward spiral approach enables us to bootstrap change out of many small efforts, but it challenges us to go beyond “preaching to the choir.” In practice, many intractable situations in business, cross-sector collaborations, personal relationships, and public life are improved through small, reciprocal actions among peers, leaders and followers, and opposing parties. The upward spiral metaphor looks for ways to use this dynamic intentionally, consciously activating higher levels of aspiration, commitment, and action — even among those who disagree.

The upward spiral metaphor prompts us to engage limits and opposition, but at a manageable angle.

For example, in a tense union-management conversation leading up to a negotiation, a mediator recognized that trust was so low that the parties involved even misinterpreted sincere collaborative behavior. Rather than continue, with the risk of a destructive strike looming, he advised both parties to stop the negotiating activity. He then asked each side to draft a list of things the other could do to demonstrate that it had turned over a new leaf and was committed to collaborating. Management’s list included “reduce work-to-rule days during critical busy periods.” Labor listed items such as “do not require physician’s notes for sick leave of less than a day.” Once complete, the two sides exchanged lists.

Over the following month or two, they watched each other’s actions. Eventually, someone tried an item on the other side’s list. Then the second side decided to reciprocate. The process built until the two sides had carried out a good portion of the items on the lists. When representatives met a second time to negotiate, though they still differed markedly in their interests, they were able to communicate critical data and forecasts more credibly and arrived at an innovative solution to avoid both a strike and difficulties for the workers. This same method has contributed to reversing destructive conflict in a variety of settings, such as helping end the violence in Northern Ireland.

Why the Upward Spiral Model Helps with Bootstrapping Change

In my experience, the upward spiral has four advantages as a model when thinking about systemic change.

1. It activates positive potential. In a downward spiral, we see the worst in people. Yet social psychology shows that human beings are not fixed entities. We can prime ourselves to act on higher values. The upward spiral image itself seems to evoke some of this energy. “I feel different just thinking about the situation as an upward spiral,” explained a teacher. “The image itself activates hope.” With renewed hope, we gain the imagination to reengage difficult situations with new perspective.

2. It works with the way systems grow. Because it is derived from the growth of living things, the upward spiral naturally invites systems thinking without requiring specialized terminology. We can use it to prompt questions such as: What do we want to grow? Are we currently growing or deteriorating? Are we near a tipping point? The spiral shape also guides us in pacing change, tackling challenges at a manageable “angle of approach.”

3. It views opposition as part of the process. The spiral metaphor reminds us that real progress requires engaging those with whom we disagree, so our efforts yield more than just a swing of the pendulum from one pole to the other (see “Progress Through Engaging Disagreement”). For example, as Barry Johnson describes in Polarity Management (HRD Press, 1996), by managing tensions through constructive engagement that integrates the best of two opposing view, we can create both/and solutions and an upward spiral based on shared purpose. At the same time, the metaphor recognizes that change often requires saying “no.” The Systems Archetypes, as defined in The Fifth Discipline and other resources, all involve rejecting some easy but ineffective solution — from quick fixes, to drifting goals, to monopolizing resources.

4. It enables us to take action whatever the circumstances. In systems thinking terms, the upward spiral metaphor works as a fractal; we can use it to spark our thinking relative to any critical resource, asset, or stock — zooming in and out as needed to any scale. We do not need to wait for others to collaborate; in fact, we can act unilaterally to help the right thing happen, addressing whatever is limiting our progress. For example, we can use it to think about growing a company’s strategic capabilities. And if we do not have enough support to act on those ideas, we can use it to think about building that support. If we do not have alignment with our boss on getting that support, we can use it to work on the relationship with our boss. The general principle is to use the resources for change that you do have, to create the resources that you need — starting with the most immediate barrier. For example, a marketing communications manager called her boss to discuss a problem with their marketing strategy, but he treated her concerns with some skepticism. Ah, she told herself. We can’t get to a shared mental model on our marketing strategy until we build some trust and rapport between us. I’ll focus on that. “So,” she said to her boss, “What do you see as the biggest barriers to achieving our goals this quarter?” By the end of the call, he began asking her similar questions.

The CPIRAL Model: Six Principles for Mobilizing an Upward Spiral

After studying examples of downward spirals, reversals, and upward spirals, I began discovering six principles that can help leaders take small, effective steps to build trust, collaboration, and excellence, even in difficult circumstances. To make these principles memorable, I captured them in what I call the CPIRAL Model:

- Center on the Asset

- Prime for Potential

- Invest in Increments

- Approach at the Right Angle

- Signal Through Action

- Listen and Amplify

Let’s examine each of these in the context of a real company in the throes of a downward spiral.

NTB was a client of mine that developed highly specialized software for government programs and was required to submit its software to citizen review committees for approval of the final product. Unfortunately, the company routinely delivered its programs months late. Code often had errors, and many of these were caught by clients, who rejected the faulty software. Programmers were often shifted from one project to another to catch up on deadlines. Stress led many of the programmers to work from home, which reduced the sense of teamwork. Angry customers changed specifications or added to project scope mid-stream. And if a project was delayed too long, the citizen review committee would complete its term, and the programmers would have to start over with a completely new set of approvers. As customers went to competitors, financial pressure mounted, so the company set hiring limits and raised targets for sales staff. Unfortunately, for the sales team to close deals, it often had to promise unrealistic delivery dates, which started the cycle all over again.

One day, sales promised five-month delivery on an 18-month project. The goal was so ridiculous that programming team members knew they had to try something different. They decided to hire a contract project manager (I’ll call him Jake). Jake said he would take the assignment but only with certain non-negotiable parameters. Skeptical but desperate, company leaders agreed.

If we do not diverge from the default pressures on the system, nothing will change.

To everyone’s amazement, Jake’s approach worked. The team completed 18 months of work in just five months, with no changes to the client’s specification (down from 10-25 percent on previous projects) and only 5 percent defects (down from 15 percent). Together with their clients, team members reversed a downward spiral of frustration and delays, and created an upward spiral of credible commitments, delivery, trust, and results.

How did they do it? And why did it work?

Center on the Asset

The first step in building an upward spiral is to ask, What do we want to grow? The answer is usually some kind of asset that enables us to generate the results we want. (An asset refers to any enabling resource, infrastructure, or stock – physical or intangible.) For example, Jake decided that he needed to drastically expand the team’s capability to deliver – the know how, systems, resources, and practices that enabled them to deliver high quality at a fast pace – if they were going to meet the deadline.

Prime for Potential

The second step is to activate hidden potential in ourselves and others by asking, What might help us see ourselves and each other anew? What are we truly capable of? A fresh look provides the inspiration to invest new energy in a situation with negative history. For example, Jake brought in benchmarks from his prior assignments showing how a few changes to work practices can multiply productivity. “Do you think we could apply those ideas here?” he asked the team. They wanted to try.

Invest in Increments

The third step is to decide: How big a step should we take next? The ideal next step contributes to the core asset, yet is within the scope of what you can manage. For example, Jake used the team’s willingness to try something different to get agreement on three small but radical changes. First, he insisted that all team members be assigned to the project full time (rather than several people part time). Second, he insisted the whole team travel to attend a kickoff so they got on the same page. And third, all developers and managers would review issues on joint weekly calls. Developers would fix their own bugs instead of handing them off to junior programmers to fix. These few changes ensured that 100 percent of team members only wrote code that fully met the client’s specifications, drastically reducing rework and waste. Despite the surface inefficiency, these practices virtually multiplied the team’s capability without adding staff hours.

Approach at the Right Angle

The fourth step invites us to set our “angle of approach”: Where do we need to differ from expectations or reach out across lines? Where do we need to say “no”? For example, Jake included downstream departments in team meetings. He vigorously resisted staff reassignments. And he disciplined his team not to write any code before the specifications were finalized. In this way, he ensured that the team only wrote code that fully met the client’s specifications and was consistent with the deadline. If we do not diverge from the default pressures on the system, nothing will actually change.

Signal Through Action

The fifth step advises us not to start with talk, but to ask ourselves, How can we signal our commitment through action? For example, Jake simply showed up at the client meeting with a list of draft specifications, then said, “Rather than give you a blank sheet of paper, we thought we’d give you something to react to. Could you review these and tell us where we’re wrong?” This helped focus the client’s input, demonstrated that the team was on top of things, and showed a commitment to customer satisfaction. If they had waited to talk through the best approach, they might not have gotten started.

Listen and Amplify

If bootstrapping change requires many small, reciprocal actions, then we can drastically accelerate that process by paying closer attention to what is already underway. We can simply ask, What can we build on? How will we know when to take the next step? For example, after a while, Jake noticed that the joint team reviews were not producing new insights. Instead, he switched to a monthly check-in, which won him kudos with the team and sparked even more productivity. Many leaders dramatically accelerate progress by watching closely as their team’s capability grows and adapting in response.

Conclusion

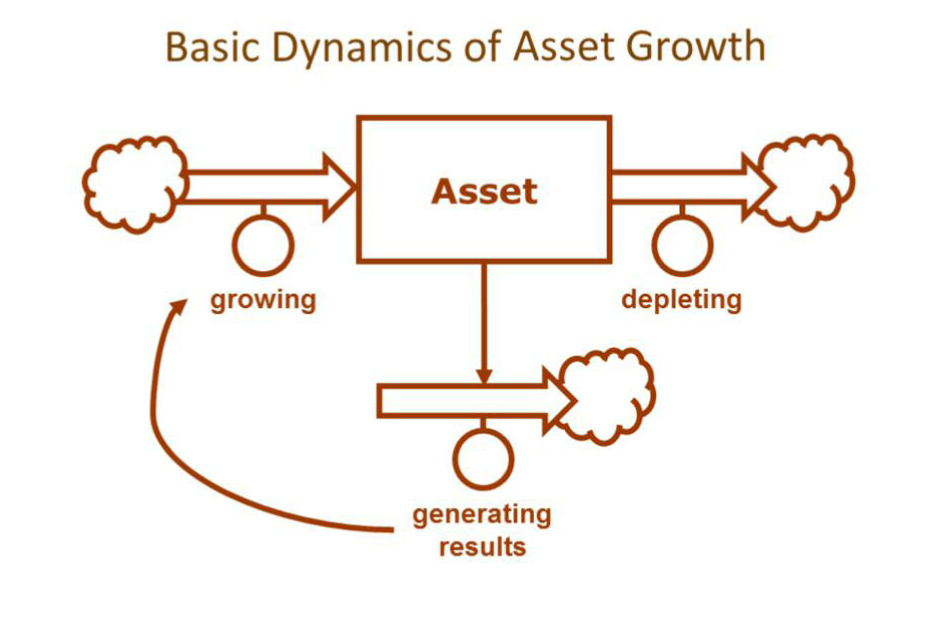

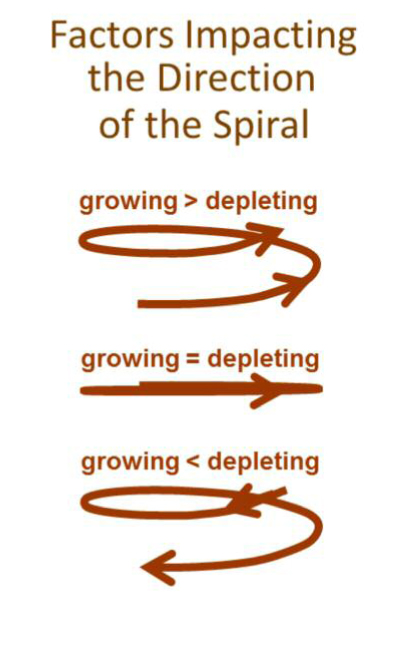

Many people ask at what point a downward spiral tips to an upward one. The answer depends on the balance between growing and depleting flows. Results improve as the asset grows, which then enables reinvestment. (See “Basic Dynamics of Asset Growth.” The structure is similar to the inflows/outflows in a bathtub.) We can tip the spiral by increasing the growing function or reducing the depleting function. In this way, a small action can transform the functioning of the system as a whole.

As you have seen above, the upward spiral model is a sort of scalable invest-for-success strategy. By taking small steps to grow a core asset or stock and working on whatever is the most immediate barrier, we can reverse destructive downward cycles and mobilize growth, health, and regeneration. What may begin as unilateral efforts to spark collaboration can enable more coordinated action and more ambitious visions.

As Robert Pirsig says in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, even the tiny screw on the cover of the gas tank deserves your respect if, by stripping it, you cannot get to the engine. When a new barrier shows up, we need to zoom in and focus on it. As we make progress, we can zoom out and take bigger steps.

There is no faster way. If we are working effectively on the true constraint, we are making maximum progress. The good news is that, in some cases, barriers can shift in an instant. At its root, the upward spiral metaphor is about choosing what to do with whatever degrees of freedom we have. And its central, driving question is always the same: How do we move up from here?

Elizabeth Doty is the founder of WorkLore, a leadership consulting firm that uses systems thinking and story to help organizations such as Cisco, Archstone-Smith, and Stanford University build cultures of commitment and action. She is the author of The Compromise Trap: How to Thrive at Work without Selling your Soul. Elizabeth has given talks and workshops at The Commonwealth Club of San Francisco, Pegasus’s Systems Thinking in Action Conference, and the Society for Organizational Learning. She is a Steward of the Bay Area Society for Organizational Learning and earned her MBA from the Harvard Business School.