Have you ever tried to drive on the left side of the road if you are born in a country in which one drives on the right? Or have you tried to use a measurement system different from the one you originally learned as a child? Or have you broken out in a sweat trying to learn a foreign language or the latest version of a software system you have been using for years? All these situations confront us with the tough challenge of replacing one behavior with a totally different one; one in which the rich combination of behaviors, knowledge, attitudes, and skills, reinforced over the years, acts as a barrier to our efforts.

TEAM TIP

Look at whether your organization supports both learning and unlearning. If you don’t explicitly support people’s process of unlearning, then they will find it difficult to adopt new behaviors.

The challenges of rapidly changing environments raise the concern: Can people’s ability to acquire new knowledge in the workplace on an ongoing basis keep up with the continuous introduction of new change initiatives/new programs/new opportunities? Organizations’ preoccupation with acquiring the latest information or knowledge rarely takes into account the processes required to reassess and release already acquired beliefs and previous learning. As result, the challenge that many organizations face when managing change programs and organizational transformation is to learn, unlearn, and relearn.

Unlearning should not be viewed as an end in itself, but as a means to ensure learning excellence, innovation, and ultimately change.

As a trainer, I have always dealt head-on with conflict, disagreement, resistance to new ideas, differences of opinion, common fears, anxieties, and feelings of incompetence in any class I have taught. A workshop with those elements is the rule not the exception and — more important — confronting the dimensions of unlearning and relearning results in more effective learning experiences that strengthen the possibilities of real organizational renewal and change. Unlearning should not be viewed as an end in itself, but as a means to ensure learning excellence, innovation, and ultimately change. I have come to believe that, to effectively train adults in the workplace, trainers must intentionally and deliberately attend to the process of unlearning and then relearning.

I have guided groups through learning and change in conditions of high uncertainty, little management support, and scarce budgets. Whether training on a new company policy, improving teamwork skills, or working on organizational transformation, I have faced unlearning decisively, with the idea that it must be confronted before the class, in the class, and after the class. In this article, I would like to share the strategies and suggestions that have proven helpful for me in supporting individual and team unlearning in the classroom.

In this article, I talk about:

- Unlearning and learning theories with a quick overview of the literature on the subject

- Three behaviors that facilitate the inner work of unlearning

- Four roles for facilitating unlearning as a team process

- Six strategies for facilitators to handle the unlearning process effectively

- Three strategies for handling the unlearning process before and three for handling it after the class

Removing the Debris

- Three hours have passed. I am in the middle of a workshop on “Facilitation Skills for Project Managers.” A man raises his hand and says, “The answers you gave are possibly correct for HR types. But you need to state and clarify to the class that, if you are not an HR type, then this is not necessarily the correct thing to do.”

- In a new system implementation class, a trainee asks a stream of questions in an increasingly confrontational tone. I give an answer and then another and then another . . . at one point, with frustration, she stands up and storms out of the room, screaming, “I am not going to take this anymore!”

- “No, thanks,” says one trainee in a workshop about effective teamwork as we talk about a way to increase effective listening., “I do not think I will use this. I understand it, but I do not believe this skill will make a difference in my teamwork.”

If these scenarios are familiar, then you have probably experienced firsthand how removing the “debris of previous construction” to rebuild the foundation for new understanding creates disorder and disorientation for the trainer as well as for the learner. While I have learned through the years not to take these reactions personally, at the beginning of my career, I often wondered how to deal ethically and effectively with people fighting the content I was teaching.

In this task, I received little help from professional training books. They call this behavior “dysfunctional” and recommend dealing with it through a mix of tact and assertiveness, with the goal of maintaining control of the class and minimizing disruptions. In fact, dismissing or labeling those behaviors did not really provide an answer to my questions:

- What are the most effective ways by which I can help the people in my class deal with letting go of old knowledge, assumptions, and ideas?

- Why do adults refuse to learn? Should adult educators protect the learner’s right to refuse to learn the content taught? If so, how?

- How can a learning facilitator be an effective facilitator of unlearning? How do we manage the process most effectively in our team learning experiences?

- How do we design instruction for adults that is unlearning/relearning friendly? How do we design/plan for unlearning/relearning?

- What role do conflict management skills and creativity play in the process? What best practices can trainers follow to handle the chaos or disruption that all this entails?

I sensed that something essential to the learning process and to the new organization whose birth we are trying to facilitate might hide in the answers to these questions.

Learning Theories on Unlearning

“I find that another way of learning for me is to state my own uncertainties, to try to clarify my puzzlements, and thus get closer to the meaning that my experience actually seems to have.”

—Carl Rogers

“Unlearning” is not the failure to learn (often treated with remediation, additional training, improved instructional activities, or sanctions) or willful non-learning — the deliberate refusal to learn and to unlearn for personal reasons. So what is unlearning?

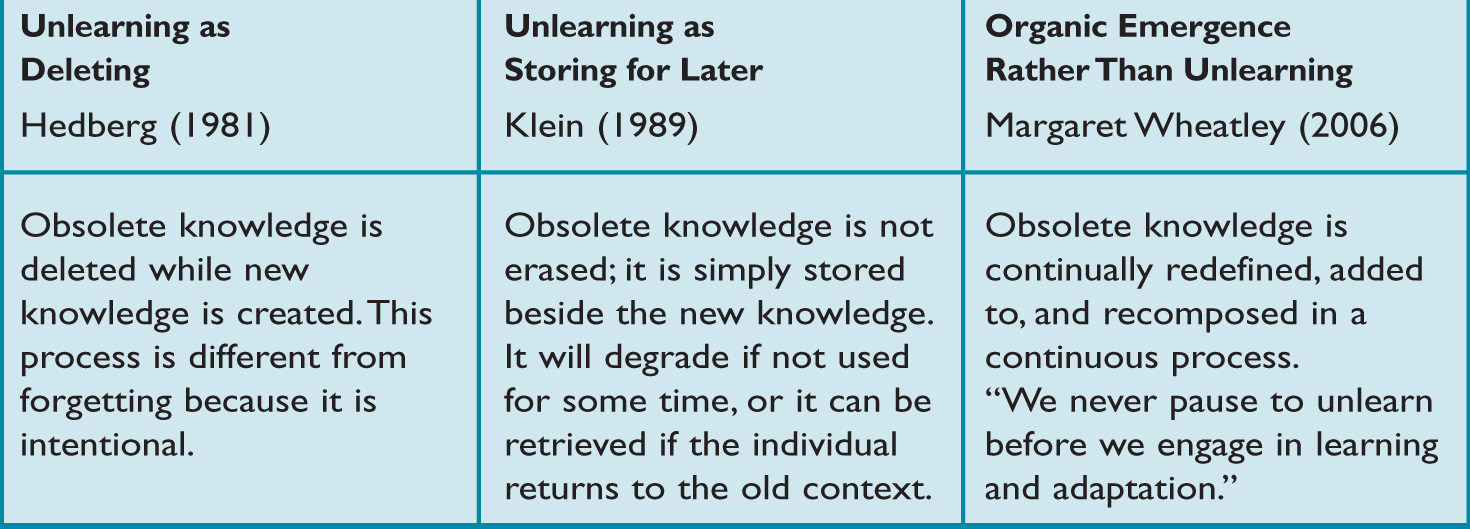

Despite a lack of empirical studies, the concept of unlearning has an important place in the learning theories of Kurt Lewin, David Kolb, Jack Mezirow, Chris Argyris, and others (see “Overview of Theories on Unlearning”). While it doesn’t use the term unlearning, Lewin’s three-stage model (the unfreeze-change-refreeze model) centers on the identification and rejection of prior learning in order to replace it. Kolb defines experiential learning as “a process whereby knowledge is created through transformation of experience” and as “A solitary act that happens in relationship with others . . . making the strange familiar” (like reflecting on unexpected events) as well as “making the familiar strange” (like reflecting on our everyday practices).

The ability to analyze what we consider “familiar” — our current way of doing things, assumptions, and mindsets—in order to experience it as “strange” is critical to the concept of unlearning. This perspective is at the heart of Jack Mezirow’s transformative learning theories as well as Chris Argyris and Donald Schön’s double-loop learning. Mezirow touched on the issue of unlearning by identifying stages of the learning process in which learners “become critically aware of their own tacit assumptions and expectations and those of others and assess their relevance for making an interpretation.” He defines emancipatory education as “an organized effort to help the learner challenge presuppositions, explore alternative perspectives, transform old ways of understanding, and act on new perspectives.” According to Mezirow, the core of transformative thinking is the uncovering of distorted assumptions. As a result, supporting unlearning is seen as engaging and questioning assumptions in the class; the job of the educator is to make those assumptions explicit, examine them, and let the learner decide whether the assumptions should be rejected or confirmed.

Argyris and Schön’s double-loop learning, a process that involves questioning the assumptions and processes that underlie errors, is centered on the idea of unlearning as making the familiar strange. In this context, learning (and unlearning) is born out of the process of uncovering the hidden incongruence between what we think we do and what we actually do. Because this process can feel threatening, to paraphrase William Noonan, the work of learning needs to overcome defensive routines that individuals in organizations use to remove conditions of embarrassment and threat. Being emotionally triggered by certain situations prevents us from learning from them. Moreover, we have become so skilled at our competence to deal with these situations that we cannot even recognize — let alone change — those behaviors. The core of double-loop learning is the uncovering of distorted mental models through a commitment to self-reflection and willingness to engage differences.

OVERVIEW OF THEORIES ON UNLEARNING

Overview of Theories on Unlearning

For the purpose of this article, I use the term unlearning to describe:

1. An individual process of personal transformation executed with the intention to change ideas, attitudes, or skills though personal emotional/ cognitive work as well as a dose of courage.

2. A group process through which individuals in learning teams build new knowledge by releasing or transforming prior learning, assumptions, and mental frameworks in order to accommodate new information or values.

Pragmatically, as facilitators of learning, we ask the following key question: In our sessions of workplace team learning—before the class, in the class, and after the class — how do we jumpstart the unlearning process and help our learners question their assumptions?

Three Behaviors That Facilitate the Inner Work of Unlearning

“If we wish to blossom, we should remember that a seed will only germinate if it ceases to be a seed.”

— The Mithya Institute for Learning and Knowledge Architecture website

How do individuals within an organization decide to embark on the journey of creating a new life or new results? Brian Hinken identifies two kinds of “awakeners” that can lead someone to “snap out of the non-learner posture” and take the first step on what he calls “the Learner’s Path”:

1. A desire to create a new life or new results (an inside-out awakener, as it originates in the internal processes of the individual)

2. Feedback that contradicts someone’s belief about the results they thought they were getting (an outside-in awakener, as it can come in the form of new data or new events)

The path to unlearning is marred by anxiety, solitude, embarrassment, and anger: upheaval within us as well as in our relationship with our world. The road to replacing assumptions, concepts, and values is uncomfortable. What does this imply for us as facilitators of learning? How can we support the unfolding of this inner process in our learners?

Rather than labeling people’s behaviors “dysfunctional,” we can do three things to help:

-

- Regards: We Must Accept Where Our Learners Are Coming From. All trainees come to a session with a rich repertoire of experiences. I find it easier to handle that baggage if I believe that everyone is always right—not moral, not legal, not correct, but always right in their circumstances of doing what they do and having the ideas they have. During the needs analysis phase of any workshop, I try to surface those difficult feelings and get ready to listen with interest.

It is tough to discover, explore, and develop ourselves if all we worry about is safety.

- Awareness: We Must Acknowledge That It Is Our Job to Deal with the Upheavals of Unlearning, and We Have to Do It Openly. Facing the process of unlearning is key. In A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, Edwin Friedman denounces the “avoidance of the struggle that goes into growth, and unwillingness to accept short-term acute pain that one must experience in order to reduce chronic anxiety.” Friedman claims that, as renaissance explorers ready to move into the unknown, we should foster a sense of adventure in our learners to prevent their “missing out on challenging opportunities to grow.” Indeed, it is tough to discover, explore, and develop ourselves if all we worry about is safety. We confront this challenge not by being in denial about it, but by seeing it as part of our job and by stressing to learners the importance of venturing out of our comfort zone.

- Compassion: We Must Bring Our Own Compassion or More to This Task. Herbert Kohl talks about his experience of helping William, an elementary school student termed an “underachiever.” He describes his first task as “helping him unlearn his sense of failure . . . cultivating his ability to resolve this sense of inferiority in a coherent and productive way.” He summarizes his most important message to William as: “I won’t let them make me stupid.” By demonstrating an understanding of the difficulties involved in unlearning, educators can nurture an inner dimension of compassion and solidarity in their students.

The Four Roles That Facilitate Team Unlearning

“I find that one of the best, but most difficult, ways for me to learn is to drop my own defensiveness, at least temporarily, and to try to understand the way in which his experience seems and feels to the other person.”

—Carl Rogers

“Uncertainty creates the freedom to discover meaning”

—Ellen Langer

How do people in a team learning experience decide as a group to identify what they have learned and if/how they want to change it? How can a facilitator of learning lead that process? I once worked with a trainer who would bring candy to class. I have always deemed such strategies ineffective for increasing motivation, as if it can be accomplished through seduction and ultimately manipulation. Instead, for unlearning, trainers need to radically rethink their role in the class and manage it according to four different dimensions:

- Host: As a host, the trainer creates a safe place for all parties where empowerment starts with comfort and freedom of expression. This role sets the stage for the unlearning process to take place. Allow plenty of time for complaining, disputing, and fighting the new content (all signs that the trainees are taking it seriously), and make it safe for the trainees to disagree with you and with the subject matter. I try to let confrontation unfold and never take disagreement personally. Instead, I view these as signs of unlearning.

- Co-Learner: As a co-learner, the trainer joins the inquiry process as one voice among many others, questioning assumptions and seeking to understand. This role stimulates an environment where assumptions — all assumptions — are worth examining and where non-defensive communication is the rule.

- Provocateur or Devil’s Advocate (also known as *#+!@ agitator): The trainer needs to challenge openly and vigorously, present new ideas, insinuate complexity, dispell comfort, and sow doubts. This role creates the premise for real creative controversy, for challenging assumptions, and for modeling the ability to deal with the ambiguity of real life.

- Supporter/Resource: In this role, the trainer assists the revision of old or inadequate concepts in an effort to facilitate the process in its entirety. This role sets the stage for a safe experience and a new beginning.

The literature often covers these roles; however, I tend to focus on the role of the trainer as provocateur, using the theory of Jack Mezirow to analyze what that role entails. The work for the facilitator here is not to manage a simple problem-solving exercise, but rather a less tidy and more involving process of self-discovery and meaningful self-revelation. In fact, people might not necessarily be aware of their assumptions, and it might be hard to make them explicit. From there, they still might not want to give them up due to their associated sense of security.

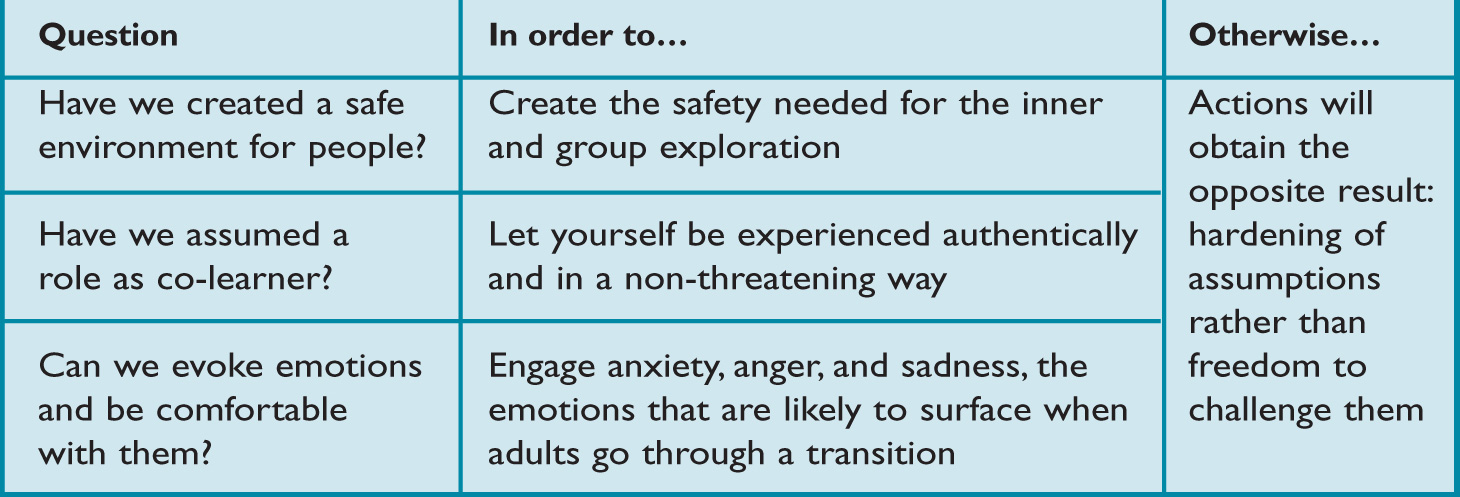

In order to deal with this challenge, Mezirow talks about a stage in the learning process of “disorienting dilemma,” a moment of confusion that jump-starts the work of critical self-reflection for transformative learning. Why does disorientation help people unlearn? Because it is in this apparent confusion that new meanings and new beginnings find their place. So, in the role of the provocateur, we must confuse our learners for their own sake. However, to be effective as provocateurs, we need to have answered “yes” to three questions (see “Three Questions” below).

Here are six strategies I have used successfully in my own workshops to facilitate team unlearning:

- State Ground Rules That Deal Openly with Unlearning. I set the following ground rules:

- Confusion is O. K.: letting go of the old brings new beginnings

- Cleverness is not O. K.: instead, seek what is truly meaningful to each of us

- Analyze the Current Mindset of the Learner in the Class. In a facilitation class, we asked participants to describe what a superb facilitator would do in a given situation. This process creates a picture of exemplary performance (e.g., “She would never let conflict derail the meeting”) that reveals hidden assumptions (e.g., “Conflict is bad for meetings”) that the trainer can openly challenge.,/li>

- Create Disorienting Dilemmas for the Learners in the Format of Case Studies to Discuss. In a training session on a new policy for a government agency, we wrote a fictional case of an architectural firm that was struggling with the same compliance issues the training was supposed to address. Two key managers described in the case — each impersonating one of the prevalent opinions about the work ahead — had come into conflict over how to deal with the issue of compliance. The dilemma was discussed in the class.

- Use “Creative Controversy” Tasks in Which Different Groups Support a Particular Position and Argue its Merit. In order to be most effective, this process needs to allow disagreement and confusion to unfold: The trainer must resist the temptation to come to the rescue with the right answer, letting the learners confront the reality that there is not a single perspective, but rather competing and discriminatory processes of establishing a truth valuation.

- Manage the Power of Feedback, Given in a Non-Threatening Way by a Fellow Learner (Not by the Facilitator), as a way to candidly reflect the learner’s action back to him or her. You might want to establish the rule of “no feedback on feedback”; recipients should respond with a ritual “Thank you.”

- Tap into Your Creativity to Surface Unexpressed Emotions. In a class, I once used the “wall of shame”: I left the room and asked this group of learners — who would clearly rather be in a dentist’s chair than in the class — to write anonymous messages on a poster that looked like a wall, stating openly (within the limits of decency) why they would rather leave than stay in the session. In another exercise with a different group, I asked that they write down their past bad experiences with the content I was teaching — their “baggage.” All their messages were read aloud, collected, locked in a tiny box, and dropped in the garbage. At the end of the class, I asked people to write the message “Goodbye . . . Welcome . . . ,” naming what they had jettisoned and what they actually gained from the class.

THREE QUESTIONS

Before and After the Unlearning Class

A trainer who deals openly with unlearning needs to address it as a process not only in the class but especially before and after it. In his classic study on the transfer of learning, John Newstrom defines the three dimensions of before, during, and after the class and maps them with the three roles of supervisors, trainers, and learners. He identifies nine possible ways for successful learned behavior to be used in the workplace. Newstrom’s findings emphasize the role of supervisors; the degree and quality of work with trainee’s supervisors before a session is the top predictor of use of the skill in the workplace.

I recommend the following activities before the class to ensure successful unlearning:

- Prepare the Client for the Rollercoaster of Unlearning. Unlearning is counterintuitive; therefore, it is important to clarify your assumptions with your stakeholders. Explain to them in advance that behaviors that are commonly termed as unprofessional (like anger and blaming) actually prove the effectiveness of the strategy.

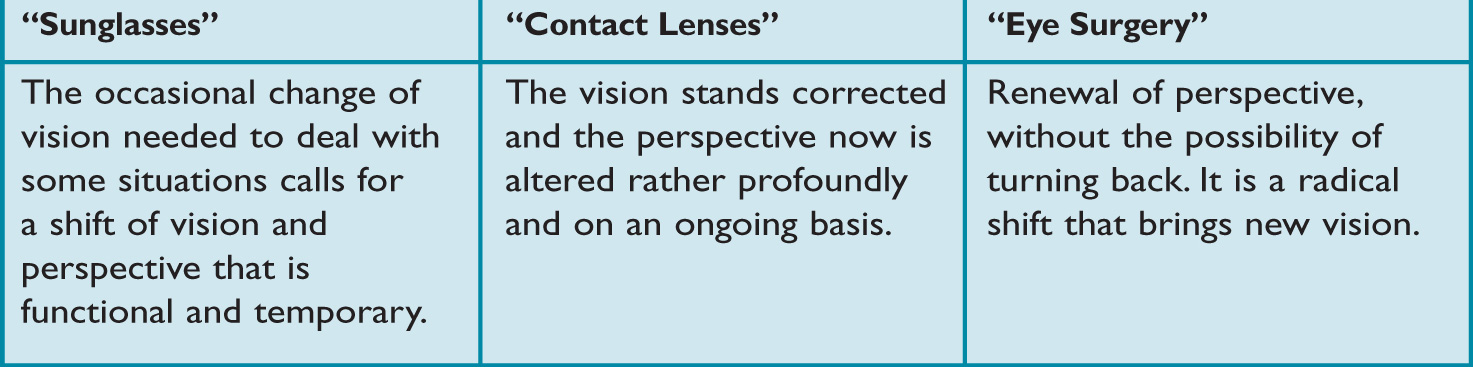

- Define Unlearning/Emergence Objectives. As is the case with learning, unlearning can have unpredictable results. The following three metaphors (“sunglasses”, “contact lenses,” and “eye surgery”) can exemplify the possible outcome of many unlearning/relearning efforts (see “Unlearning Outcomes”). Define the objective of your class in advance. Keep in mind that, while unlearning/relearning is the fuel of healthy organizational culture, it is not required for every workshop, for every client, and to the same extent in every case!

- Add Time to the Agenda (based on your objectives) to allow conversations to emerge that deal with the unlearning process. I normally schedule an hour for unplanned activities that might be necessary to support unlearning.

The creation of support mechanisms (formal and informal) that identify and manage the emotional and cognitive work of unlearning after the class is also an important factor in successful unlearning — and represents a great problem for limited training engagements. While many desire the benefits of unlearning, only a few understand that it cannot happen without an expense of time and effort. The following is a list of low-cost activities that can be used to engage a community of non-learners after a class:

- Create an Online Community. This work ensures that your learners continue to use each other and you to bring about the change that unlearning empowers.

- Ask the Supervisors to Meet with the Learners After the Class. In this meeting, learners engage with their direct supervisors in a conversation about how to bring about the changes that unlearning entails.

- Create Informal Events (Happy Hours, etc.). These activities allow for the camaraderie and fellowship of the learning community to continue to support its unlearning effort.

An Openness to Experience

“Wisdom comes along through suffering’’ says the poet, and the philosopher reminds us that “The truth of experience always implies an orientation toward new experience.” The openness to experience in general, to new things, to new ideas is addictive. As facilitators of learning, we need to cultivate that openness in ourselves and in our learners.

UNLEARNING OUTCOMES

Adriano Pianesi is the principal of ParticipAction Consulting, Inc., and has 15 years of experience in the non-profit, government, and private sector in training adults, course development, facilitation, and e-learning. A certified Action Learning coach and Harvard Discussion Method expert, he teaches workshops in the areas of facilitation, train-the-trainer (training design, development, and delivery), teamwork, customer service, and supervisory skills. His clients include the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation, the USDA Graduate School, the National Labor Relations Board, Keane Federal Systems, Silo smashers, Serco North America, Aderas, and MRIS.

For Further Reading

Becker, Karen Louise. Unlearning in the Workplace: A Mixed Methods Study, Queensland University of Technology Thesis, 2007

Broad, Mary L., and John W. Newstrom. Transfer of Training: Action-Packed Strategies to Ensure High Payoff from Training Investments (Addison-Wesley, 1992)

Cranton, Patricia. Understanding and Promoting Transformative Learning: A Guide for Educators of Adults (Jossey-Bass, 2006)

Delahaye, Brian, and Karen Becker., “Unlearning: A Revised View of Contemporary Learning Theories?” in Proceedings from Lifelong Learning Conference, 2006

Duffy, Francis M., “I Think, Therefore I Am Resistant to Change,” Journal of Staff Development, Vol. 24 No. 1, Winter 2003

Kohl, Herbert. “I Won’t Learn from You” and Other Thoughts on Creative Maladjustment (New Press, 1995)

Macdonald, Geraldine., “Transformative Unlearning: Safety, Discernment and Communities of Learning,” Nursing Inquiry, Vol. 9 No. 3, 2002

Mezirow, Jack, and Associates. Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning (JosseyBass, 1990)

Soto-Crespo, Ramon E., “The Bounds of Hope: Unlearning ‘Old Eyes’ and a Pedagogy of Renewal” in Thresholds in Education (May and August, 1999)