Over several years, I had developed a strong relationship with the leadership team of a $3 billion division of a Fortune 100 organization. A shuffling of portfolio and responsibilities had precipitated a 360-review and a new leader assimilation and coaching process for the global senior vice president of manufacturing, Sam Allard. As part of the coaching process, Sam invited me to observe a business meeting of his global manufacturing team in which they were discussing key priorities and agreeing on the strategic agenda for the year ahead.

It was a long day of heated discussions with little agreement or progress against an ambitious agenda. Sam asked how I thought it had gone. I recall saying, “It depends on your desired outcome. If success meant getting through the agenda and getting resolution on the issues, you did not meet that objective. If, however, you wanted to get a view of the team dynamics, I believe you had a very successful meeting.” He laughed and said, “What should I do about this situation? I need a team of VPs who can work together to create uniform standards of manufacturing that are necessary for us to achieve our revenue and profitability targets. Can you help me?”

Team Tip

The Team’s Current State

In the meeting I attended, I observed a team that was ill equipped to work in a collaborative and productive manner. Some of the behaviors I saw included:

- An inability to focus on an agenda and make decisions

- A lack of willingness to engage in dialogue

- Poor capacity to listen to one another

- An apparent lack of respect for one another’s ideas

- A tendency to personalize the conversation and get defensive

These observations led to some preliminary hypotheses — that the group lacked trust and the willingness to operate as a team; that they were focused on furthering their individual agendas; and that they would be unsuccessful in creating a standardized manufacturing platform for the company unless they were able to come together and operate with mutual respect, trust, and a willingness to listen to and learn from each other.

In the meeting I attended, I observed a team that was ill equipped to work in a collaborative and productive manner.

During conversations concerning Sam’s 360-review, I had developed a rapport with each member of the team. I leveraged this to have open and honest discussions on what I’d observed during their business meeting. One of them commented, “It was embarrassing to have you witness that meeting. That is so typical of the way we operate. It’s a challenge to get through an agenda with this group.” These one-on-one conversations helped validate my hypotheses around specific concerns and enlisted the executives in Sam’s overall objective — of creating a cohesive team who could work well together in executing an aggressive and critical element of the organization’s strategy.

I also used a team effectiveness questionnaire from Edgar Schein (from Process Consultation: Its Role in Organization Development, Addison-Wesley, 1988, p. 57–58) to get the team to self-assess and have a structured view of their current effectiveness. When I shared the results of this assessment, one of the executives commented, “I had no idea we were so disruptive in the way we operated.”

Based on the assessments, and with Sam’s agreement, my mandate for a 12-month engagement was to create a team that:

- Made sound business decisions in a considered and timely manner

- Had the ability to work together to solve critical production and quality issues

- Engaged in meetings that were productive, energetic, and constructive

- Showed evidence of listening, collaboration, and mutual respect

- Set aside personal agendas and depersonalized the conversation

- Collaborated to develop and implement a world-class manufacturing strategy

The Design of Interventions

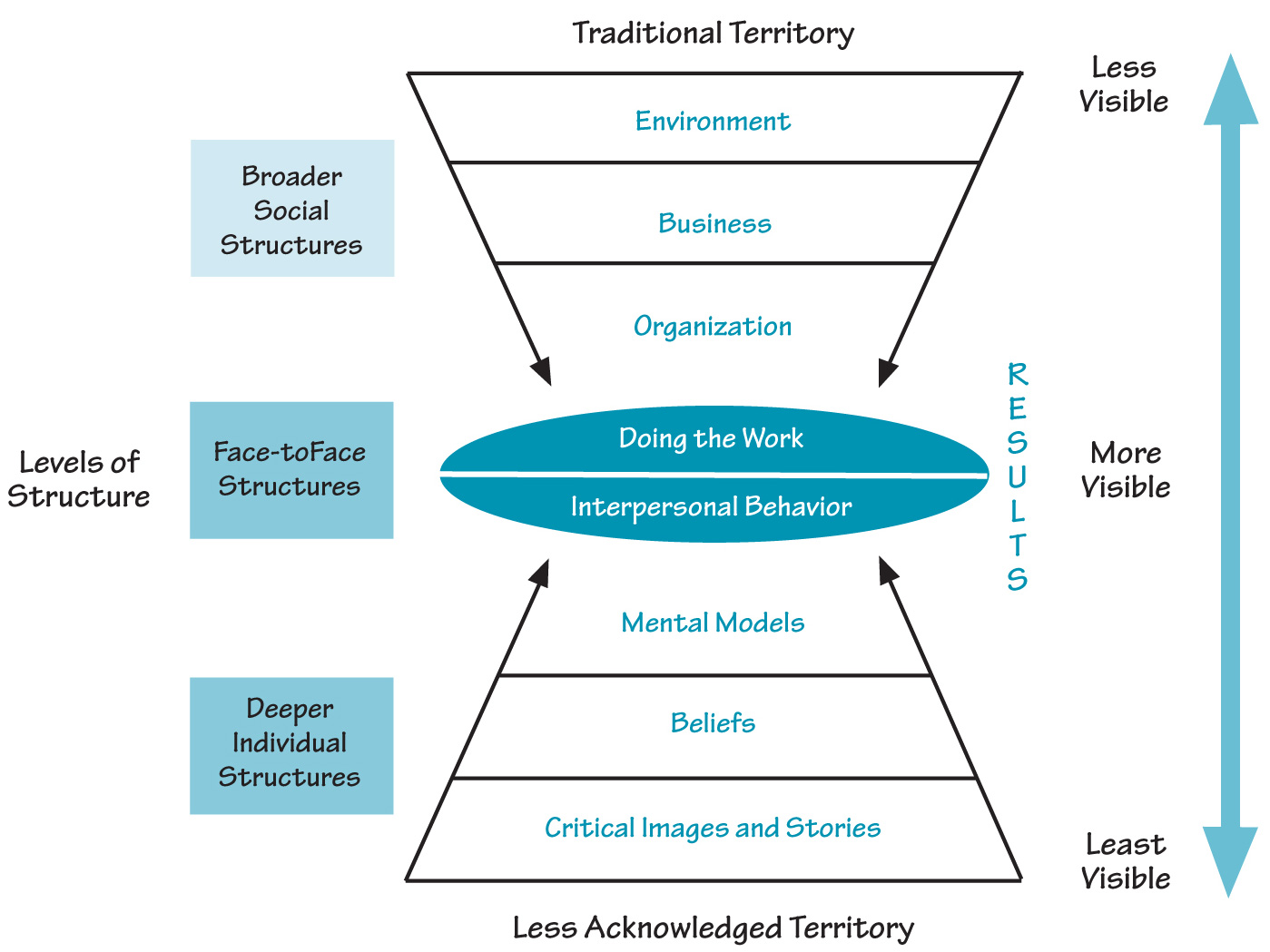

I saw this as an amazing opportunity to delve into territory that is typically not explored. I based the design of my interventions on a model of human structural dynamics derived from the work of David Kantor (see “Human Structural Dynamics Model”). This model suggests that human interactions are a function of the social context in which they take place and of what goes on in people’s hearts and minds (Ober, Kantor, Yanowitz, “Creating Business Results Through Team Learning, The Systems Thinker, V6N5, June/July, 1995, pp.1–5). I chose to focus on two aspects of this model—the team or what is described as the face-to-face structure, and the deeper individual structures and how they might influence the team’s interactions, either one-on-one or in the team.

HUMAN STRUCTURAL DYNAMICS MODEL

I chose to include individual-level interventions because they cover ground that is typically less acknowledged and yet significantly impacts behavior — what we see at the face-to-face level. It also meshed well with my belief as an OD practitioner that all change starts with individual change, and that our behavior as adults is strongly influenced by our mental models, core beliefs, and stories — many of these arising from experiences in our formative years. I had a sense that if I was able to allow for the surfacing and at some point sharing of deep imagery from each individual, it would help this team coalesce and begin the process of trusting each other.

The Team Interventions

At the team level, the interventions were designed to help develop trust and connection, and start to develop the capacity for listening. The following models, beliefs, and assumptions influenced the choice of interventions:

- A high-performing team is characterized in part by strong personal commitments to the growth and success of each team member (Katzenbach and Smith, The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High Performance Organization, Harper Business, 1993).

- Appreciation of individual experiences and gifts is a powerful foundation for transformation and allows for creation of powerful outcomes (Cooperrider and Whitney, Appreciative Inquiry, Berrett Koehler, 1999; Elliott, Locating the Energy for Change: An Introduction to Appreciative Inquiry, International Institute for Sustainable Development, 1999).

- The ability to listen deeply allows for connection and a foundation for collaboration and “thinking together” — the essence of dialogue (Isaacs, Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together, Currency/Doubleday, 1999).

- Dialogue fosters and maintains the high levels of openness and trust that are present in healthy teams.

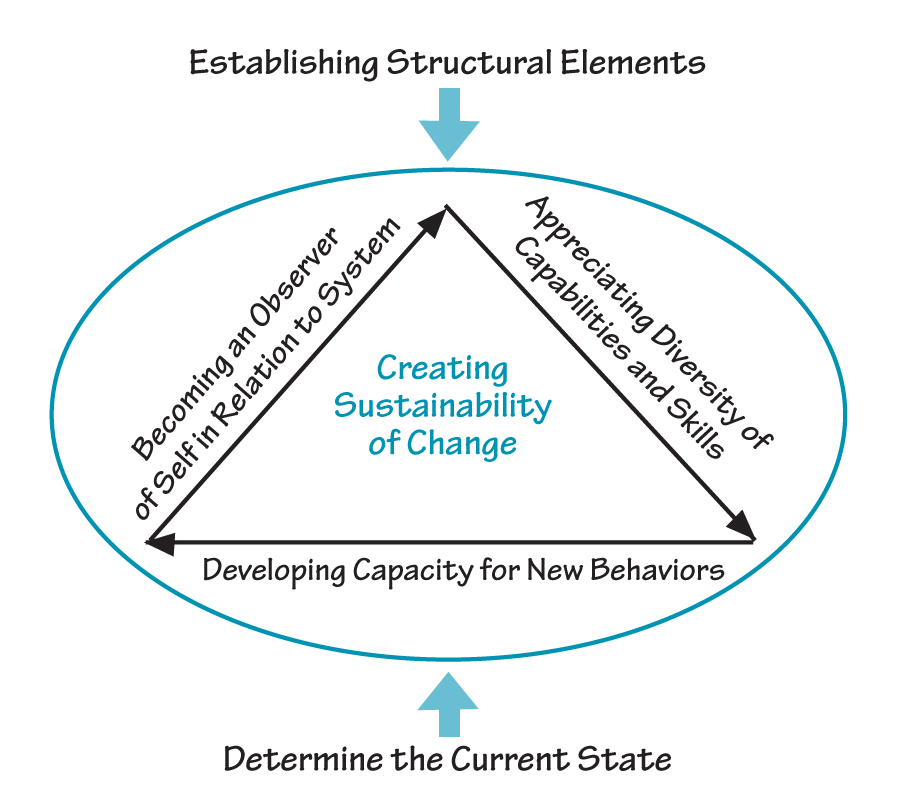

“Progress Toward Trust and Cohesiveness” demonstrates how the different elements were integrated to guide the team’s progress toward trust and cohesion. In addition to determining the current state, five other building blocks contributed toward creating a team that was able to sustain behavioral changes that enabled an environment of trust, collaboration, and cohesiveness:

Establishing Structural Elements. Sam wanted the team to own and follow basic housekeeping guidelines. This set of interventions was aimed at establishing a process by which the team could focus its discussions and deliberations and make decisions in an effective manner. It involved clarifying roles and responsibilities, delineating decision rights, and setting up operating guidelines between Sam and his team, as well as within the team.

PROGRESS TOWARD TRUST AND COHESIVENESS

The interventions were integrated to guide the team’s progress toward trust and cohesion.

Developing the Capacity for Deep Listening and Dialogue. The more challenging aspects of this engagement were around creating a safe container for the team to have strong dialogue. To achieve this, I introduced the principles and intentions of council to structure the meetings (Zimmerman and Coyle, The Way of Council, Bramble Books, 1996; Baldwin, Calling the Circle: The First and Future Culture, Bantam, 1998). These principles included always being seated in a circle and using a talking piece that the team co-created. The intentions of council are speaking from the heart or being honest and authentic; listening from the heart or being deeply present and attentive when another speaks; being “lean of expression” and learning to be succinct; and allowing for silence as well as spontaneous expression.

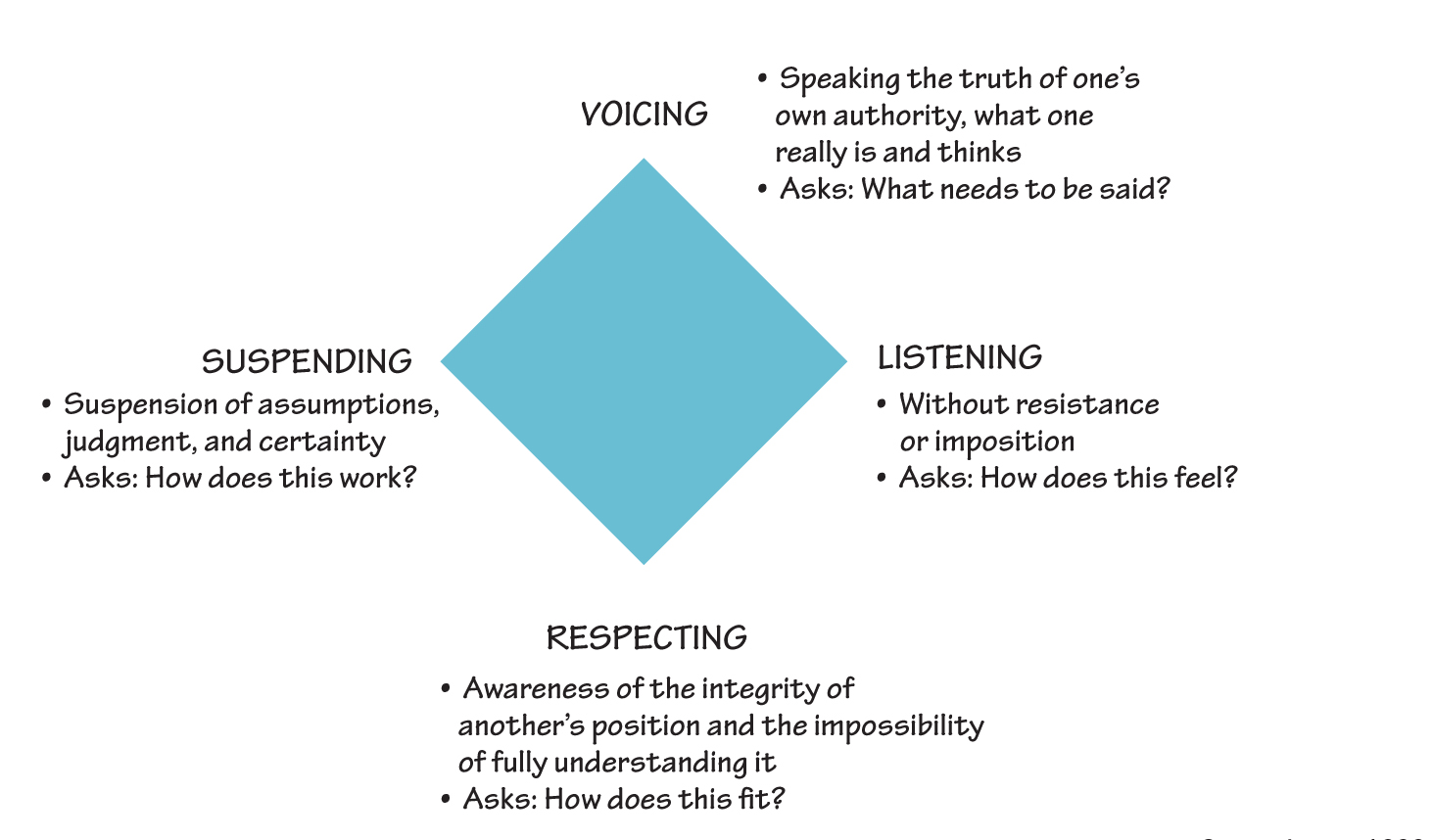

To facilitate their interactions within this structure and to help them make the distinctions that would allow them to realize the intentions of council, I introduced the four behaviors of dialogue as described by Bill Isaacs — voicing, listening, respecting, and suspending (see “Developing the Capacity for New Behaviors”). At one level, the intention was to help the team develop a capacity for listening without judgment and reaction, and at another it was aimed at helping them experience how deep listening could result in more powerful outcomes and decisions. Above all, it was aimed at building trust within the team.

DEVELOPING THE CAPACITY FOR NEW BEHAVIORS

The four behaviors of dialogue as described by Bill Isaacs are voicing, listening, respecting, and suspending.

Over the course of my engagement (and subsequently), the team adopted sitting in a circle as part of their meeting protocol. Initially they struggled with the some of the practices of council — in particular with holding a silence. They tended to reach for the talking stick before the person who was speaking had finished. Over time, as they became more comfortable with the practices, the use of the talking stick as a mechanism to allow “one voice at a time” and to help “hold the silence” evolved from a forced behavior to a more natural and comfortable one. Their discussions went from individuals fighting to say their piece to comments that were more indicative of listening and building on what has been said. The reaction to silence went from a rush to fill it to actually asking for a moment of reflection during the course of a conversation. Although there was evidence of progress, it was more of an iterative process than a linear progression. The awareness and reinforcement of dialogic behaviors was one that continued throughout my 12-month engagement with this team and continues to be a core part of the team’s operating model.

Appreciating the Diversity of Skills and Capabilities. While most of Sam’s team had been at this company for many years and had deep roots in the industry, some of the more recent additions were brought in with different industry experience, including experience in creating world-class manufacturing organizations. The input of these individuals was often not considered and valued by their colleagues. As Sam put it, “I hired Joel and Charisse for their expertise in Lean Manufacturing. I am concerned the rest of the team is shutting them out. I suppose I could be more directive by simply telling people we have to rely on their experience, but I don’t want to add to the resistance.”

The team needed to operate in an environment of respect and appreciation for the diversity of style, skills, experiences, and contributions. They also needed to understand how to work effectively with this diversity and leverage the strengths of each other. To create this culture and capacity, I used interventions derived from Appreciative Inquiry, team role preference (Margerison and McCann, “Team Management Profiles: Their Use in Managerial Development,” Journal of Management Development, Vol 4, No 2, pp 34–37, 1985), and individual assessments such as DiSC as building blocks on the foundation of dialogue.

These interventions had the desired impact. For instance, the Appreciative Inquiry exercise used in the first session allowed for a breaking of the ice in the team. The team found many points of connection — shared experiences, interests, hopes, and desires. After that session, some of the sources of tension dissipated, such as the resentment of the role an individual played or the lack of industry experience. In addition, the resistance to being seen as and operating as a team started to fall away as they worked through their stories of positive team experiences.

In using the Team Management Profiles, the team was able to appreciate the different work preferences and styles that were present in the room. It allowed them to identify strategies that would be most effective in interacting with this group of individuals and to value the different roles each member of the team tended to prefer in a team setting. It also gave them a snapshot of what might be missing and how they could develop those roles as a collective.

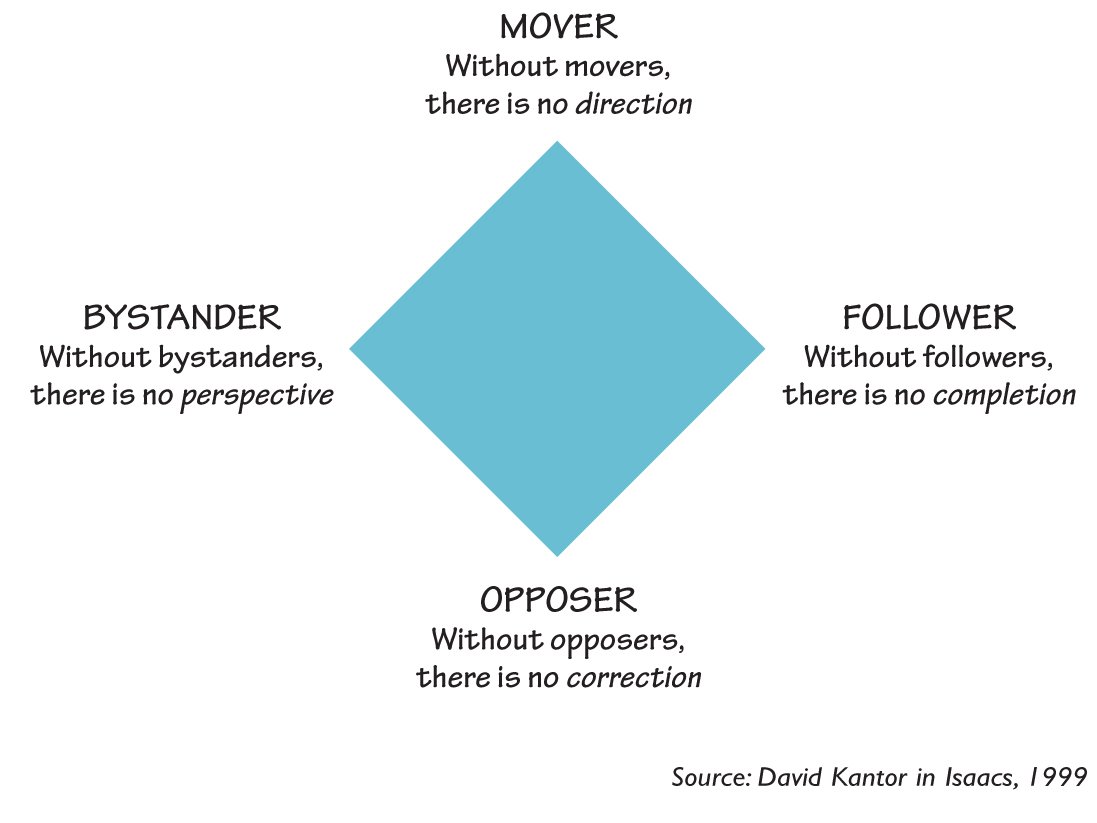

Becoming an Observer of the Self. As I worked with the team, I felt it was important to facilitate the development of their capacity for diagnosis and action in order to make them self-correcting and self-sustaining after I had transitioned out of the process. I also wanted them to have a greater awareness of how to facilitate a dialogue by understanding the roles they tended to gravitate to in a conversation. I introduced another element of structural dynamics — that of boundary profiles and, more specifically, David Kantor’s “four-player system” (Kantor and Lonstein, “Reframing Team Relationships: How the Principles of ‘Structural Dynamics’ Can Help Teams Come to Terms with Their Dark Side,” The Fifth Discipline Field book, Currency/ Doubleday, 1994).

My intention was to get this team of individuals to see their patterns of interaction. I believed if they were conscious of their operating tendencies, how these impacted their effectiveness, and what roles were being played out in their team interactions, they might be able to shift the roles they played and engage in more productive and effective dialogue. It would help them notice whether their conversations were dialogic in nature or at the level of discussion and debate. At a minimum, it would increase their self-awareness of how they showed up and help them develop a capacity to become observers of their own behavior. To facilitate their learning, I videotaped some of their meetings and had them analyze their interactions afterward.

One of the insights that emerged was the difference in expectations of how the team should operate. For instance, Sam expected his team to be his equal partners in the decisions they made. There were some members who would defer to Sam’s decisions. Another insight came from seeing two members of the team frequently engaging in a move-oppose dynamic and how it stymied the progression of the conversation.

Creating Sustainability of Change. The emphasis of each intervention was to help them not only become familiar with the skills but also to practice and develop a level of mastery with that skill. Each session built on the previous ones. The final intervention was a visual image storytelling process (Reeve, Creating a Catalyst for Change via Collage Inspired Conversations, unpublished Master’s thesis, Fielding Graduate University, 2005) where the team incorporated the various building blocks (i.e., practices of dialogue, appreciation and knowledge of self and other, and observation) to co-create their vision for their team. It required them to collaboratively create the guiding principles and core values of the team, and the behaviors that would govern their interactions going forward, by building on the values and vision of each individual. I chose a visual process to shift the context from the verbal, left-brain activities that this team was facile with to a process that would invite them to activate in a positive way some of the drivers of their behavior — their beliefs, values, and mental models. As the team moved from sharing individual values and beliefs to co-creating a shared set of guiding principles and vision, they exhibited respect for individual ideas and the diversity of opinions. There was a remarkable absence of the heated arguments that had characterized the first meeting I’d attended. In its place was an energy of collaboration and partnership, resulting in the creation of a shared vision that each individual had contributed to, owned, and had personalized through the storytelling process.

The Individual Interventions

While working with the team as an entity, I was also coaching individual members. A core outcome for the coaching sessions was to help the individual become an observer of the self and understand what drove behavior so they were able to choose how to act, rather than acting from a place of habitual tendency. The ultimate goal for the “Human Structural Dynamics Model” is authenticity; insight, mastery, and alignment are intermediate stages that lead to authenticity. In an effort to be pragmatic (and recognizing the journey toward authenticity is a lifelong one), I focused on a realistic goal of building the capacity for insight through self-awareness and inquiry into the underlying causes of behaviors, along with varying degrees of mastery.

Using a subset of the human structural dynamics model as a base, I worked to help each individual become aware of their feelings, mental models, belief systems, and deeper stories that governed their behavior in the team context. Specifically, the intent was to make visible those factors that were invisible or less visible and enable the individual to act in an authentic manner.

As I used this model to guide the individual coaching sessions with each executive, my role evolved in the following manner:

- Help the individual become aware of feelings, mental models, belief systems, and deeper stories

- Create and strengthen their capacity for embracing these deeper structures

- Facilitate their understanding of how these structures impact their behavior and how to recognize the shadow aspects

- Help them develop the ability to reframe and choose the internal structures that influence behavior

Interplay Between Individual and Team Interventions

Having simultaneous interventions at the individual and team levels and playing a dual role as facilitator for the team and as personal coach allowed me to observe shifts that occurred as individuals gained insight into their behavior and changed how they interacted with the team. The team meetings also provided me with direction on how to intervene at the individual level with different executives.

The Results

Over the 12-month period, there were many visible changes at both the team level and with individuals. For instance, the team’s interactions were much less fractious and chaotic. Their discussions resulted in key decisions being made in a timely manner with each individual feeling heard even if their idea was not included. They had greater appreciation and respect for what their colleagues brought to the team, “I had no idea Charisse had such wide-ranging experience. It is quite refreshing to have someone who hasn’t grown up in this industry.”

They were able to appreciate silence and the quality of reflection and insight that came from it, “I realized how much of my time is filled with doing things — meetings, conference calls. I never get time to think. I was actually able to think about and find a solution to this problem.” There was a greater sense of camaraderie and trust among them. In self-assessing their progress on the team effectiveness instrument used at the beginning of the process, on all measures, the team had moved from a “below average” score to an “above average” rating.

When I started my work with the team, I would have described members as exhibiting behaviors characteristic of “breakdown.” Probably one of the more profound changes I saw was their ability to maintain a quality of inquiry. At rare moments, particularly in our last session together, there were moments when their interactions had elements of flow.

At the individual level, the changes varied depending on the person. Certainly some of them moved more than others. As their capacity to observe their own behavior grew, it created greater awareness and ownership of their own issues, and led to more courage and honesty in their communications. As they stepped in to appreciate and value their own contributions and role on the team, their insecurities went down; they developed more confidence and demonstrated a greater sense of presence as leaders. The awareness and legitimizing of their individual stories allowed them to have respect for and appreciation of the same in others. By practicing compassion for themselves, they developed the capacity for compassion toward others. This in turn allowed for a level of trust and a commitment to each other’s success, which provided a strong basis for collaboration.

Critical Success Factors

I was operating at two levels of the system simultaneously and addressed not only the behaviors that emerged in team interactions but also the underlying triggers of these behaviors. One reason I was able to successfully take this path was Sam’s uncompromising sponsorship and support, as well as the trust we had built as a result of our long-standing relationship and my candor in the early stages of the engagement. Over the course of the 12 months, he allowed me tremendous creative freedom to introduce the ideas behind council practices and dialogue. He’d been exposed to the practices and was a great believer in the notion of “going slow to go fast.”

BEING A REFLECTIVE PRACTITIONER

In the course of this engagement, I found myself engaging in a great deal of reflection around my capacity as an OD practitioner. At various points, I explored different questions, including:

- What is my typical stance with clients?

- How am I showing up? How does it feel?

- How do my own inner stories and mental models influence me?

- How can I consciously choose to shift from my “tendency”?

- What will it take to shift my stance to what is needed?

- What is the impact if I shift my stance? What is the risk if I don’t shift my stance?

The process of being both coach and facilitator provided me with a powerful illustration of the importance of having a strong container for individual and collective transformation. I was constantly stepping into a place of modeling the behaviors I introduced to the team — learning to honor silence; bringing a mindset of appreciation to the conversation; making the invisible visible in my own context; acting with courage in situations that challenged me personally, such as not being compelled to have all the answers, not taking their resistance to some of the ideas I introduced as personal criticism, and being a mirror for them when situations that contributed to the dysfunction in the team came up.

I used this engagement to expand my comfort zone. Since I was working closely with this team over a significant period of time, I took a reflective stance for each encounter and expressly asked, “What could I have done differently to make this session more effective for you?” It allowed the team to see that it was acceptable to not be perfect; it gave me a chance to get real-time feedback that could improve my capacity as a facilitator and helped me explore my own growing edge around feedback and criticism.

Another area I consciously worked with was to develop my ability to let go of managing the outcome. I actively practiced being present to and responding more in the moment — operating with a sense of connection to my own insight and intuition, with powerful positive outcomes. This engagement built my capacity to be an observer of myself and of the system. It has strengthened my ability as an intervener and has contributed significantly to the development of my voice and my own transformation.

Although some members of the team were initially resistant to the team process, because of my work with them individually, they grew to trust me with their inner stories and thus trust the process I was taking the team through. Their cynicism and resistance started to wear down as they experienced having a voice in the conversation and being heard as a result of using council and dialogue practices.

One of the other unexpected contributors to the success of the engagement was my knowledge of the organization, its business, and the dynamics within the industry. It allowed me to connect the interventions aimed at strengthening team effectiveness to core business issues the team was dealing with, rather than have “stand-alone” team-building sessions. By integrating business issues into the design of the interventions, the team had an immediate context for applying and practicing their new skills, which enhanced the capacity for retention and recall of new behaviors.

Challenges Encountered

There were some challenges during the course of this engagement. Even as they saw the value of the practices of council and dialogue, the team didn’t readily embrace some aspects. It took a while for them to honor silence and not jump into the fray. “I find it so difficult to sit still and not say something when no one is speaking. It makes me wonder if I did something wrong,” said one of the executives early in our sessions. While this reflected the challenge of holding silence, it was also a powerful example of how our inner story shows up in our behavior. Over time, and with the help of reflective practices in their individual coaching as well as in their team sessions, they started to see the value of having silence and silent time in their process.

Another difficulty that was more present in earlier sessions than in later ones was a desire to be “in action.” This is reflected in the comment from a team member that “we talk a lot and I enjoy our sessions, but when do we make decisions for the business?” Fortunately, given Sam’s experience with dialogue, he was able to support me and provide a context of “We are making decisions. By talking about and resolving the issues, our decisions are becoming clearer.” It took them a while to realize that by being in dialogue, they were “in action” around decisions.

In creating the experience of being an observer of the self and using the four-player model, there were some unintended consequences. During the debrief, one of the team commented,

The human structural dynamics model provided a valuable set of lenses to examine this team’s issues.

“We sure were on our best behavior today. I suppose we knew we were being watched.” Had I anticipated this better, I might have introduced a disturbance to the system to raise the stakes, because when the stakes are high, people tend to revert to “default” or typical behaviors, especially in early stages of behavioral change.

Summary

The human structural dynamics model provided a valuable set of lenses to examine this team’s issues. At the same time, it allowed for improvisation in the choice of interventions used to address different team issues. The occasion to work with an intact team over an extended period of time helped create a robust foundation wherein the skills introduced had a chance of taking hold. It helped build trust with each individual and created a space for personal growth. This systemic approach presented a powerful learning opportunity for all of us engaged in the process.

A longer version of this article appears in Reflections: The SoL Journal on Knowledge, Learning, and Change, Volume 9 Number 1. For more information, go to www.solonline.org/reflections.

Deepika Nath (dnath@indicaconsulting.com) is the founder and principal of Indica Consulting, where her focus is on bridging strategy and organizational development to bring about growth and lasting transformation. She is a trusted advisor and coach to senior executives seeking to define an authentic and effective leadership style. Her experience spans 15 years of strategy and organizational consulting with leading firms such as the Boston Consulting Group and Ernst &Young. A member of SoL, she holds a PhD in Management and an MA in Organizational Development.

NEXT STEPS

Guidelines for Working with Our Learning “Selves”

The following guidelines and practices may be useful in a continuing journey toward a more expansive, open, and “learning” self:

- Practice saying “I don’t know” whenever appropriate. You may find it to be quite freeing to admit that you don’t know something.

- Learn to “let go” of the need to be in control of yourself or others. In order for us to learn, we must care more about learning than about being in control.

- Continually challenge yourself to hold your perceptions up to the light. This means continually studying them from all angles. Remember that these beliefs may reflect more truths about yourself than about reality.

- Admit when you are wrong. Try to freely and openly admit when you are wrong (or admit that your assumptions may be inaccurate even the first time you state them!).

- “Seek first to understand, and then to be understood.” Steven Covey suggests asking yourself, “Do I avoid autobiographical responses, and instead faithfully reflect my understanding of the other person before seeking to be understood?”

In “Opening the Window to New Learning” by Kellie Wardman, Leverage (Pegasus Communications, Inc., May 1999)