As we approach not only the November elections but also Lincoln’s 200th birthday, it seems appropriate to reflect on his legacy. Why do so many consider him to be the greatest American president? Regardless of one’s office, what lessons can we learn from such an individual to apply in our own organizations?

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s epic biography of Lincoln, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (Simon & Schuster, 2005), is no better place to explore the answers. By interweaving the biographies of members of Lincoln’s cabinet, Goodwin creates a systemic portrait of the administration that saved the Union. Through this meticulous examination of the interrelationships among this group, we learn about its leader with a richness that would be unlikely any other way. Remarkably, many of these men were political rivals. Yet in spite of the conflict among them as well as surrounding them, Lincoln forged a team that would prevail.

What struck me most while reading Team of Rivals was how the lynchpin of Lincoln’s prodigious emotional intellect was his empathy. Time and again, Lincoln’s insights into others deescalated conflict and cemented relationships, both personal as well as political. Building on Goodwin’s painstaking research into the people and events of Lincoln’s life, this article examines the relationship between Lincoln’s empathy and the following facets of his emotional intelligence: deescalation, storytelling, self-awareness, self-regulation, humor, and reflection.

TEAM TIP

Take inspiration from successful leaders and teams, wherever you may find them – history, sports, music, or science.

Popular culture sometimes offers the two-dimensional image of Abraham Lincoln as a moral but depressed emancipator. Goodwin introduces us to his depth as a man who was “plain and complex, shrewd and transparent, tender and iron-willed” (p. xv). He displayed, “a fierce ambition, an exceptional political acumen, and a wide range of emotional strengths, forged in the crucible of personal hardship, that took his unsuspecting rivals by surprise” (p. xvi). Goodwin observes that “Lincoln’s political genius” allowed him “to repair injured feelings that, left untended, might have escalated into permanent hostility; to assume responsibility for the failures of subordinates; to share credit with ease; and to learn from mistakes… His success in dealing with the strong egos of the men in his cabinet suggests that in the hands of a truly great politician the qualities we generally associate with decency and morality — kindness, sensitivity, compassion, honesty, and empathy — can also be impressive political resources” (p. xvii).

Empathy and De-escalation

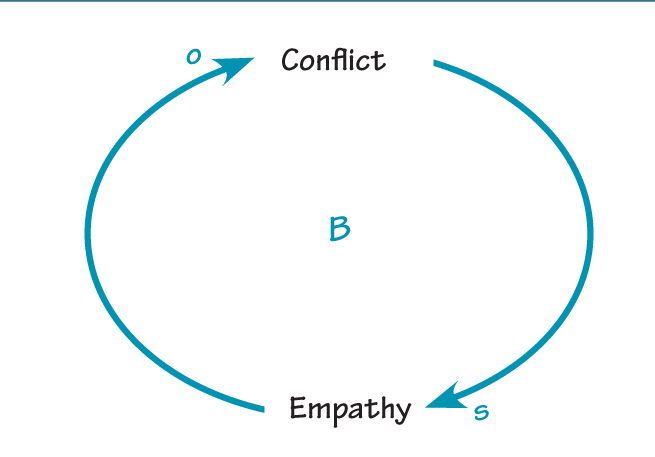

When I first wrote the outline for this article, I listed empathy and de-escalation as separate sections. It became readily apparent, however, that virtually every example of Lincoln’s empathy was an example of de-escalation; their relationship was causal (see “Conflict/Empathy Cycle”)

CONFLICT/EMPATHY CYCLE

One way to think about how Lincoln’s empathy affected his ability to manage conflict is with a balancing loop. As conflict increased, it caused his empathy for the other party to increase. As his empathy increased, it reduced the conflict. As the conflict then decreased, Lincoln could focus his attention elsewhere. As his empathy for the other party went down, sometimes the conflict would return. This cycle would then repeat.

Goodwin begins her exploration of Lincoln’s empathy with its relationship to his melancholy. Lincoln “possessed extraordinary empathy — the gift or curse of putting himself in the place of another, to experience what they were feeling, to understand their motives and desires… His sensibilities were not only acute, they were raw.” As a young man, Lincoln once “stopped and tracked back half a mile to rescue a pig caught in a mire – not because he loved the pig, recollected a friend,‘just to take a pain out of his own mind.’” Helen Nicolay, the daughter of Lincoln’s private secretary, concluded, “With his wealth of sympathy, his conscience, and his unflinching sense of justice, he was predestined to sorrow.”

Yet in the political arena, this same sensitivity would be Lincoln’s greatest asset. Nicolay astutely observed that, “His crowning gift of political diagnosis was due to his sympathy… which gave him the power to forecast with uncanny accuracy what his opponents were likely to do.” After listening to colleagues at Whig Party caucuses, Lincoln would extrapolate:, “From your talk, I gather the Democrats will do so and so… I should do so and so to checkmate them.” He would intuit “the moves for days ahead; making them all so plain that his listeners wondered why they had not seen it that way themselves” (pp. 103–104). In this way, Lincoln’s empathy did not prevent him from competing politically; to the contrary, it enabled him to do so successfully.

The duality of his empathy as both a blessing and a curse is a recurrent theme in his life. Lincoln’s trips to visit troops in the field exemplify this dynamic. His bodyguard, William Crook, observed how Lincoln “seemed to absorb the horrors of the war into himself.” Lincoln experienced “agony when the thunder of the cannon told him that men were being cut down like grass” and anguish at the “sight of the poor, torn bodies of the dead and dying on the field of Petersburg.” His “painful sympathy” was extended impartially not only to “the forlorn rebel prisoners” but also to “the devastation of a noble people in ruined Richmond” (pp. 723–724).

The Civil War would present innumerable opportunities for Lincoln’s empathy to de-escalate a potential conflict and transform it into a valued relationship. In one instance, three Confederate slaves being used to build a rebel battery escaped from their master. The Union general Benjamin Butler refused to return the slaves to their owner on the grounds that the slaves were being used to further the rebel cause. As Butler was a conservative Democrat, his action was unusual. Despite their political differences, Lincoln rewarded Butler by promoting him to brigadier general. In a letter to Lincoln, Butler wrote that he accepted the commission but wished to be frank that in the prior election he had done everything he could to oppose Lincoln. He reassured Lincoln that, “I shall do no political act, and loyally support your administration as long as I hold your commission; and when I find any act that I cannot support I shall bring the commission back at once, and return it to you.”

Lincoln replied with typical magnanimity: “That is frank, that is fair. But I want to add one thing: When you see me doing anything that for the good of the country ought not to be done, come and tell me so, and why you think so, and then perhaps you won’t have any chance to resign your commission” (pp 368–369). How many senior leaders are secure enough to order their subordinates to disagree with them? Lincoln recognized that surrounding yourself with those who are willing to disagree with you builds error-checking into your decision-making.

Lincoln’s empathy not only gave him insight into the suffering of others, it aided him in communicating these insights.

Nor was Lincoln beneath apologizing. Goodwin describes that when Lincoln found out “a hastily written note to General Franz Sigel had upset the general, he swiftly followed up with another.‘I was a little cross,’ he told Sigel,‘I ask pardon. If I do get up a little temper I have no sufficient time to keep it up.’ Such gestures on Lincoln’s part repaired injured feelings that might have escalated into lasting animosity” (pp. 511–512).

Lincoln’s friends were more likely to hold political grudges on his behalf than he was. When a congressional colleague celebrated the defeat of a political rival, Winter Davis, Lincoln remarked, “You have more of that feeling of personal resentment than I. A man has not time to spend half his life in quarrels. If any man ceases to attack me, I never remember the past against him” (p. 665).

Lincoln’s empathy not only gave him insight into the suffering of others, it aided him in communicating these insights. When Lincoln’s secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton, refused to grant a political appointment desired by two congressmen, Lincoln eloquently supported the decision. Lincoln described Stanton to the congressman as “the rock on the beach of our national ocean against which the breakers dash and roar, dash and roar without ceasing. He fights back the angry waters and prevents them from undermining and overwhelming the land.” Lincoln marveled at Stanton’s very survival in a position that was “one of the most difficult in the world,” and therefore saw that it was his “duty to submit” to his secretary’s decision. By so doing, he led the congressmen to do the same (p. 670).

Lincoln’s famous second inaugural address in 1865 (“With malice towards none; with charity for all”) was once again guided by his empathy – even for a war-time enemy. Goodwin observes, “If the spirited crowd expected a speech exalting recent Union victories, they were disappointed. In keeping with his lifelong tendency to consider all sides of a troubled situation, Lincoln urged a more sympathetic understanding of the nation’s alienated citizens in the South.” Lincoln represented the North and South as being more the same than different:, “Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes” (p. 698).

One cannot help sense that for Lincoln “the other” equaled “the self.” Nowhere was this clearer than in Lincoln’s orders regarding the re-assimilation of enemy soldiers after they surrendered. When General Sherman asked for guidance on how to handle the defeated rebels, Lincoln answered that “all he wanted of us was to defeat the opposing armies, and to get the men composing the Confederate armies back to their homes, at work on their farms and in their shops.” Lincoln wanted the citizens of the South to “have their horses to plow with, and, if you like, their guns to shoot crows with. I want no one punished; treat them liberally all round. We want those people to return to their allegiance to the Union and submit to the laws” (p. 713).

One the greatest sources of conflict within Lincoln’s cabinet was his secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase. A former rival during the 1860 bid for the presidency, Chase never stopped campaigning, in some form, even while a member of Lincoln’s cabinet. When this conflict finally came to a head and Chase resigned, Lincoln still did not write him off. To the contrary, he nominated him to be chief justice of the Supreme Court. When Lincoln first announced this nomination to one of Chase’s friends, the colleague was dumbfounded:, “Mr. President, this is an exhibition of magnanimity and patriotism that could hardly be expected of any one. After what he has said against your administration, which has undoubtedly been reported to you, it was hardly to be expected that you would bestow the most important office within your gift on such a man.”

Lincoln’s reply was matter-of-fact: “To have done otherwise I should have been recreant to my convictions of duty to the Republican party and to the country. As to his talk about me, I do not mind that. Chase is, on the whole, a pretty good fellow and a very able man. The only trouble is that he has ‘the White House fever’ a little too bad, but I hope this may cure him and that he will be satisfied.”

Lincoln would later confess that he “would rather have swallowed his buckhorn chair than to have nominated Chase” (p. 680). He was still human; he clearly felt the sting of his former secretary’s insubordination. He simply did his best to rise above his own ego in service of a greater good.

Storytelling

Crafting a story that connects with an audience is ultimately an act of empathy. Lincoln was a seemingly bottomless treasure trove of anecdotes for all occasions. He learned this craft from his father, Thomas. But before he could learn how to tell stories, Lincoln first learned how to listen.

As a young boy, Lincoln would sit “transfixed in the corner” listening to his father’s colorful anecdotes. He would then spend “no small part of the night walking up and down,” putting his father’s stories “in language plain enough, as I thought, for any boy I knew to comprehend.” Goodwin recounts that “The following day… he would climb onto the tree stump or log that served as an impromptu stage and mesmerize his own circle of young listeners” (p. 50).

As an adult, Lincoln’s stories became more than mere entertainment: “They frequently provided maxims or proverbs that usefully connected to the lives of his listeners. Lincoln possessed an extraordinary ability to convey practical wisdom in the form of humorous tales his listeners could remember and repeat” (p. 151). His mastery lay in the ability to distill complexity into terms that anyone could understand, thereby enabling others to propagate his considered insights.

Navigating the intense factions of slavery would provide perhaps the greatest test of these talents. Approaching the 1860 convention, one hotly contested national issue was whether slavery should be allowed to spread to the new western territories. Over several speeches, Lincoln refined the following metaphor to describe the decision facing the nation:, “If I saw a venomous snake crawling in the road, any man would say I might seize the nearest stick and kill it; but if I found that snake in bed with my children, that would be another question. I might hurt the children more than the snake, and it might bite them… But if there was a bed newly made up, to which the children were to be taken, and it was proposed to take a hatch of young snakes and put them there with them, I take it no man would say there was any question how I ought to decide… The new Territories are the newly made bed to which our children are to go, and it lies with the nation to say whether they shall have snakes mixed up with them or not.”

Goodwin insightfully contrasts this rhetorical approach of Lincoln’s with that of his future secretary of state, William H. Seward. Seward likened slavery to allowing “the Trojan Horse” to enter the territories. While such a classical allusion might have reached Seward’s peers, it lacked the “instant accessibility” to the average citizen of Lincoln’s “homely” story (pp. 233–234).

Lincoln’s rhetorical approach to slavery had grown out of his prior experience with another divisive issue: temperance. In each case, empathy with both sides enabled his insightful understanding of the issue. He advocated that temperance activists avoid “thundering tones of anathema and denunciation,” for such tactics would only be met with more of the same. Independent of the truth of one’s cause, whether it be temperance or slavery, condemning one’s opponent would only cause him to “retreat within himself, close all the avenues to his head and his heart.” The heart, alone, was “the great high road to his reason” and therefore must be reached first to win another over (pp. 167–168). Creating an effective path to do so could only be accomplished by first standing in the other’s shoes.

Goodwin observes that “as a child, Lincoln had honed his oratory skills by addressing his companions from a tree stump” (p. 140). As an adult, these skills would become Lincoln’s connection with people. Lincoln understood that the most important responsibility of his office was to educate:, “With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed. Consequently, he who molds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts or pronounces decisions” (p. 206). His molding of public sentiment was achieved through storytelling, and his storytelling was made effective through his empathy.

Self-Awareness and Self-Regulation

Lincoln was not merely aware of the emotions of others; he also possessed an acute awareness of his own emotional needs. In spite of a tendency towards melancholy, this awareness enabled him to self-regulate his moods more effectively than any other member of his team, providing a critical foundation of emotional stability in the midst of national instability (p. xvii).

The essence of self-regulation is first having the awareness of one’s emotional needs and then acting to meet them. Lincoln knew intuitively when he had to make “a deposit” in his personal “hope account,” as well as those of others. One activity that sustained not only him but also others was his strategically timed visits to the troops in the field. The sight of Lincoln in his stovepipe hat would elicit cheers from the troops. The act of the president visiting their camps in person – at no slight personal risk – gave the troops inspiration, and inspired troops inspired Lincoln. Seeing each other escalated hope. Attending plays at Grover’s or Ford’s theaters would become another favorite means for Lincoln to achieve emotional “respite and renewal” (p. 609).

Humor

The theater was also an arena in which Lincoln exercised another self-regulation mechanism: his prodigious sense of humor:, “His ‘laugh . . . stood by itself. The neigh of a wild horse on his native prairie is not more undisguised and hearty’” (p. 613).

Meanwhile, as with his empathy, his melancholy was the shadow side of his humor. Goodwin emphasizes a distinction between depression and melancholy, the latter containing “a generous amplitude of possibility, chances for productive behavior, even what may be identified as a sense of humor” (pp. 103, 723). His humor was a willful way out of this “cave of gloom.” Lincoln laughed, he explained, “so he did not weep… His stories were intended ‘to whistle off sadness’” – not only for others but for himself as well.

Lincoln’s humor wasn’t just for humor’s sake; he had an uncanny ability to meld humor into the gravest of circumstances, often providing resolution without offense. During peace talks with a Confederate envoy, the envoy offered King Charles I as an example of a figure who made numerous agreements “with his adversaries despite ongoing hostilities.” Lincoln responded, “I do not profess to be posted in history… All I distinctly recollect about the case of Charles I, is, that he lost his head in the end” (p. 693).

When the career of his recalcitrant secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase, was on the line, Chase wrote Lincoln asking for an audience. It is hard to read Lincoln’s classic reply without yearning for an opportunity to use it:, “The difficulty does not, in the main part, lie within the range of a conversation between you and me” (p. 632).

Much to the consternation of many in the army – but not surprisingly – Lincoln was liberal with issuing military pardons. Such weighty decisions were yet another opportunity for Lincoln to deftly interweave empathy and humor. Lincoln wrote the following passage as part of a pardon to an army officer who was facing a court-martial for giving in to his temper during an altercation with a superior officer. Just as noteworthy is to whom this paternal wisdom is being imparted: the brother-in-law of none other than Stephen Douglas, Lincoln’s one-time political nemesis:

No man resolved to make the most of himself, can spare time for personal contention. Still less can he afford to take all the consequences, including the vitiating of his temper, and the loss of self-control. Yield larger things to which you can show no more than equal right; and yield lesser ones, though clearly your own. Better give your path to a dog, than be bitten by him in contesting for the right. Even killing the dog would not cure the bite (p. 570).

Lincoln could find humor in every nook and cranny of daily experience. During one of his visits to the front, he traveled on a naval flagship. Turning down the admiral’s own room, Lincoln insisted on taking a cramped room only “six feet long by four and a half feet wide” (p. 715). Lincoln joked the next morning that while he had slept well, “you can’t put a long blade into a short scabbard.” During the day, the Admiral arranged for carpenters to knock down the wall and enlarge both the room and the bed. The next morning, Lincoln “announced with delight that ‘a greater miracle than ever happened last night; I shrank six inches in length and about a foot sideways.’”

Pausing to Reflect

Lincoln rarely acted in anger. This was not because he was immune to anger but because his self-awareness guided him to pause to reflect before acting.

Writing was one act that was conducive to such a thoughtful dynamic, observed Lincoln’s secretary, John Nicolay. Lincoln frequently wrote using a process of cumulative refinement, coming back to a passage over days or weeks to hone it to his satisfaction. As a result of the well-crafted substance of his writings, Lincoln’s oratory has withstood the test of time.

Salmon P. Chase’s ambition for the presidency tested Lincoln’s composure more than once. The release of a pamphlet critical of Lincoln’s administration was the last straw. But by holding back from admonishing Chase when the circular became public, Lincoln gave his friends the opportunity to rally in support of him. In this way, Lincoln thwarted Chase without having to take direct action, thereby moderating the potential personal conflict between them.

The self-discipline of pausing to reflect allowed Lincoln’s empathy to return to the forefront of his decision-making and be the guiding force behind his actions, rather than his anger. When General George Meade failed to capture Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, Lincoln was initially inconsolable and penned “a frank letter” to the general. While being grateful for his success at Gettysburg, Lincoln admonished him for “the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape.” As a result, “the war will be prolonged indefinitely.” Before sending the missive, however, Lincoln must have thought through the emotional consequences upon the reader. Years later, the letter would be discovered in an envelope labeled, “To Gen. Meade, never sent, or signed” (p. 536).

Lincoln’s Leadership Legacy

Lincoln created a systemic understanding of his time by reading hearts and minds through empathy. In popular culture, empathy is sometimes derided as a form of weakness. Lincoln’s life challenges this stereotype. We create the world around us through our own actions. Lincoln consistently forged function out of chaos with magnanimous gesture after magnanimous gesture. These gestures, in fact, helped Lincoln secure the 1860 Republican nomination, not because he had the greatest experience, but because he had the fewest enemies. Such circumstances were manifest by his empathy throughout his career.

Surely, the positive effect of his approach was magnified because of his office. Executive empathy wields more influence than subordinate empathy. Even so, during the turbulent days of the Civil War, the impact of Lincoln’s legacy had its limitations. While he was able to save the life of a nation, he was ultimately unable to save his own.

How would Lincoln’s behaviors clash with our modern technologies? If one’s response to an angry letter is crafted with a fountain pen and delivered by horseback, pausing to reflect is built into the process. Modern wireless communications technologies discourage such reflection. What are the consequences? What are our choices?

Through his empathy, Lincoln saw everyone in terms of a potential relationship, a connection worth nurturing. With such an enlightened consciousness, is anyone a rival?

It is difficult to reflect on Lincoln and his time without reflecting on our own fragile, fractured world. Perhaps hope for informed action comes in the form of a simple question:, “What would Lincoln do?”

NEXT STEPS

Empathy and De-escalation. Take a walk in your rivals’ shoes. What are they seeing? Feeling? What are their fears? Their insecurities? How might these insights inform your actions?

Storytelling. Identify the essence of the complexity your organization is facing. What anecdote would distill that essence into terms with which your audience would not only connect but enjoy repeating? What universal parable is right for this moment?

Self-Awareness. Take an inventory of your moods. Do your emotions support or hinder your purpose?

Self-Regulation. What productive detour might help realign your heart with your intention? Where are your organization’s “front lines”? Who are your “troops”? Visit them where they are. Give yourselves permission to celebrate each other.

Humor. How many times have you told a story of a conflict from ages past – only to laugh as you told it? What’s absurd about this current conflict? Is it possible to summarize any serious advice with humorous kindness?

Pausing to Reflect. Do you have to respond to an attack immediately? Reflect on the potential benefits of waiting before reacting. Of the conflicts that you are currently engaged in, which might sort themselves out in time – all by themselves?

All excerpts copyright © 2005 Blithedale Productions, Inc.

Peter Pruyn lives and writes in Cambridge, MA and can be reached at pwp [at] airmail [dot] net. Special thanks to Rick Karash whose recommendation inspired him to read Team of Rivals. For more of the author’s work see http://peterpruyn.blogspot.com.