Over the years, many people devoted to sustainability have used the phrase “the triple bottom line” to articulate strategy. They don’t focus solely on economic bottom-line activities: profitability, financial performance, or even the capacity to make a living. Instead, they judge success according to social and environmental results as well: by their ability to improve the natural environment and make people’s lives better in society as a whole. The “triple bottom line” concept represented a great improvement over the constraints of a purely financial point of view, in which environmental and social results (including such business needs as customer satisfaction) were perceived as costs or externalities.

But ultimately, the triple bottom line is not sufficient. Initiatives based solely on this concept as a rationale — for example, efforts to change a company so that it can consistently produce “triple-bottom line results” — often seem to falter. Moreover, the focus on the triple bottom line may draw people away from the qualities and attitudes they need if they are to genuinely make a difference in developing sustainable organizations, practices, and communities.

TEAM TIP

Emotions can be valuable as a kind of barometer — an indicator that there is something we need to reflect upon and figure out if we want our actions to be effective.

There seem to be two reasons for this. First, the way that most people operate with the triple bottom line ignores the real synergy among its three dimensions — social, economic, and ecological. In practice, efforts tend to be fragmented: Companies institute “social policies,” “green practices,” and financial reporting systems without ever linking them together. By contrast, projects with deep linkages can be powerfully effective. One example is the initiative by Dr. Macharia Waruingi to eradicate malaria in his home country of Kenya. This project connects investment in local businesses (which builds economic infrastructure), with the development of business capacity to make and sell mosquito repellent and bug nets, the reduction of environmental toxins, and the creation of local community support.

The second reason that a focus on the triple bottom line alone isn’t enough is that it allows people to ignore the “inner work” — the personal practices and disciplines that provide the perspective and internal stability needed to make a difference in the long run. The very ideals and aspirations that lead people to an interest in sustainability can also drive people into a frenzied cycle of “fixes,” actions, and imperatives, ultimately leading to wasted efforts and burned-out people. For our own sake, and that of the results we hope to produce, we need to prevent this from happening.

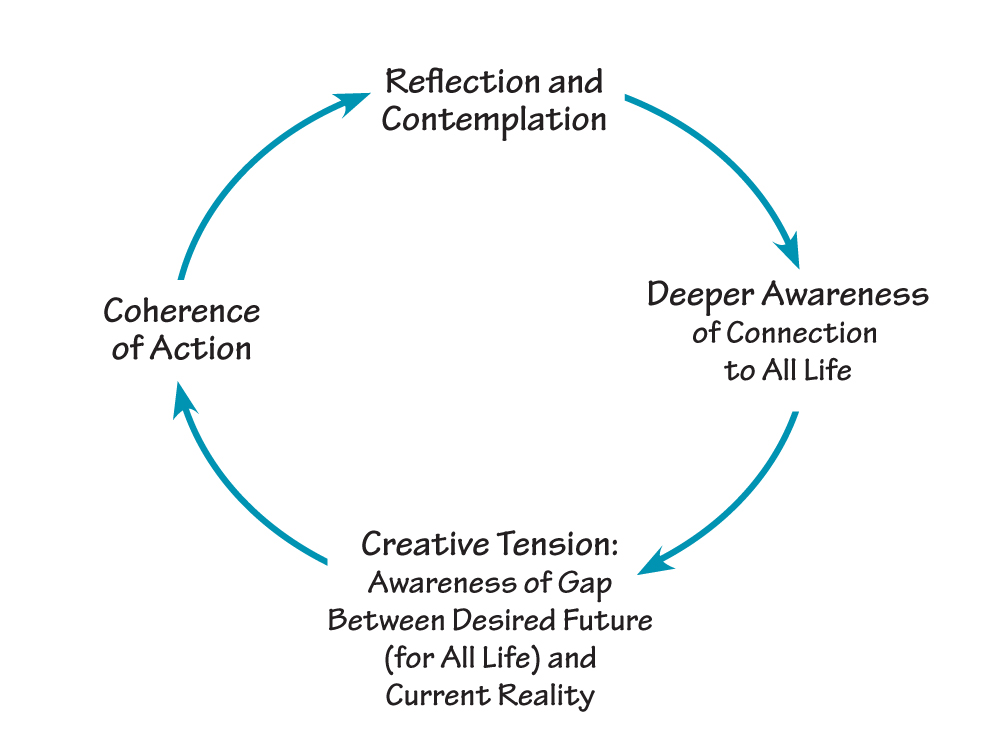

The answer lies in the inner work of sustainability. A reinforcing process is set in motion when people start to deliberately slow down their lives to cultivate broader awareness and reflective practice. The cycle, if we were to map it in systems thinking terms, would look something like “The Cycle of Inner Work.”

THE CYCLE OF INNER WORK

Deeper Awareness of the Connection to All Life

In college physics, years ago, I learned that the equation for gravitational attraction on the planetary scale is virtually the same as the equation for gravitational attraction on the atomic scale. In other words, “as above, so below.” The structures at the largest astronomical scale are echoed in the structures of our cells. These correspondences are not obvious to the naked eye, and they may not be predictable, but they are far more powerful than people often expect.

Awareness of the underlying interconnectedness of life, wherever it started for you, may well lead you to feel a greater sense of responsibility for the whole. At heart, this represents a shift in mental models. You and I may start to see that our lives are interconnected with the lives of all living entities on earth, from microorganisms to all people to the ecosystem of the planet as a whole. We may gain a humble awareness that the small choices we make, day by day — what to consume, how to handle our garbage and waste, how to conduct our work, and how to spend our time — do indeed have effects on the larger systems around us. We may also start to recognize that our ability to care about others — people on far-flung continents, people in unfortunate circumstances, people caught in disasters, or people anywhere in the chain of life — makes a difference. We have creative and destructive capacity: We can act to contribute to life, healing, and generativity, or we can act with violence and fragmentation. When writer Janine Benyus said, “We have to fall back in love with nature,” she was speaking in part about the importance of embracing this sense of interdependence. In my view, it makes an enormous difference to anyone’s perspective and capabilities when they not only intellectually see interconnection, but emotionally feel it.

Creative Tension

Awareness of our connection to all things is a kind of vision; it leads us to wish for a better quality of life and equity for all people on the planet. At the same time, as this sense of connection to others increases, we become more aware of the suffering and problems that exist around us. Despite the success we may experience in our own individual professional and private lives, we come to recognize more coherently the gap between the world as it is and the world as it could be.

Stronger awareness of the gap, in turn, leads to one of two responses. First, as Joanna Macy and Dana Meadows have noted, it leads to denial and despair: People often throw up their hands and retreat into a shell. But confined spaces are boring, and sooner or later many of us emerge, aware of the gap that needs to be closed and interested in learning how to do our part to close it.

We may have an increased desire to take coherent action to bridge the gap for others, and for life in general. People who feel this desire are then more likely to take action “in service of life,” with a more intensive desire to improve the economic, cultural, social, and environmental well-being of all. In the process, people learn, bit by bit, to live with emotional tension, that is, to tolerate the fact that the gap between vision and current reality exists. And then we allow a different kind of tension in ourselves, the natural movement to close the gap, to come to the surface.

Creative tension leads to better results. If we are attuned to the gap between vision and current reality, we pay more attention to the signals that come back to us in response to our actions.

Coherence of Actions

Creative tension leads to better results. If we are attuned to the gap between vision and current reality, we pay more attention to the signals that come back to us in response to our actions. Either our actions have produced the results we want and moved us closer to our aspirations, or they haven’t. And if they haven’t, we will pick up those signals and our actions will become more effective and coherent.

As people’s capability and awareness grow, they choose to do better things — things naturally more in line with the aspirations of an integrated triple bottom line. These actions are inevitably more diverse than the habitual behaviors of people acting primarily in terms of their own self-interest. More coherent actions produce a wider variety of feedback — responses from the world — which naturally leads people to want to make sense of those responses, in the mind, body, and heart. This increases the value of the contemplative state.

Personal Contemplative Practice

Most of the successful people I know in the sustainability field regularly follow some discipline of contemplative practice. In workshops on sustainability, my colleagues and I often ask, “How many people set time aside for reflection or contemplation in some disciplined way?” Lately, nearly every hand goes up.

Like the individuals who practice them, forms of contemplation vary dramatically. People might practice prayer, meditation, yoga; walking in the woods, running on a track, or, in the case of one CEO we know, beekeeping. But all such practices have this in common: They quiet the mind, decrease the static in our systems, and allow us to put the treadmill of everyday life on hold. They sharpen our ability to see current reality and act in accordance with our aspirations for self, family, community, and world.

Midwife and Buddhist teacher Terri Nash says that actions that are not grounded in contemplation do violence; to the extent they are grounded in some form of reflective practice, they become more coherent. The reverse is also true. As actions become more grounded and coherent, the quality of contemplative practice goes up.

In turn, as personal consciousness (developed through whatever reflective discipline is chosen) increases, a person’s innate awareness of the connection to all life increases. Anyone who has practiced contemplative work recognizes this. And thus the reinforcing cycle is closed.

Contemplation is a critical part of the cycle, not just because of the mental process of reflection, but because of the cessation of the normal cycle of activity and consumption. One common practice, observing the Sabbath or Shabbat, is taking a day of rest, but not just from work: from other everyday activities such as shopping, talking on the telephone, and using e-mail. I know people who practice this faithfully from Friday evening to Saturday evening every week. That day is spent in awareness of the perfection of creation. No one buys anything because nothing is needed. No one talks on the phone or travels because perfection exists where we are, and with whoever is nearby. There is no television, Internet, or other media. The day is spent taking walks in the woods, exercising, meditating, connecting with family members and friends, dancing, conversing, laughing, and sharing meals. It adds up to a taste of the world to come. The boundaries set around that day make it a day of tremendous freedom.

And observing Sabbath or Shabbat influences habits for the rest of the week as well. On Sunday morning, the reasons for anxiety and stress, so overwhelming on Friday, are difficult to remember. The impetus to make needless purchases is gone. That in turn makes it easier, during the rest of the week, to resist otherwise addictive drives to push, grow, and consume.

The Role of Emotions

My colleagues and I have noticed that, for many people, the journey to sustainability begins with emotion. We may hear a report that 30,000 children will die of starvation after a natural disaster has occurred. There may be reason to believe that global climate change is involved in triggering the disaster. And we feel not just a sense of connection, but grief (mourning the loss), anger (“How was this allowed to happen?”), or fear (“Could this happen again?”) We may also feel the sense of joy that naturally arises when people are connected to each other and to the natural environment. For a variety of reasons, although we may have ignored these emotions in the past, we find them compelling us now.

The reader of this article may be used to thinking of emotions as destructive. Emotions can emerge in destructive ways. But emotions can also be expressed in constructive ways. Primary emotions have evolved in the human species over millennia. Anger and fear are hardwired in our biological systems, as are grief and joy. When we disown these emotions, we deny ourselves vital information that can be used to stay alive and achieve our aspirations. In many situations, emotions can be valuable as a kind of barometer — an indicator that there is something we need to reflect upon and figure out if we want our actions to be effective.

Emotions also play a critical role in organizational life. There is always a temptation to view businesses in an industrial-age way, as machines with people operating in the cogs; in such a view it seems appropriate to devalue emotions. What machine feels? Corporate cultures have developed a stoic resistance to emotions: People are supposed to “suck it up” and not express anger or fear. The mental model is that emotions make it harder to get work done. But not only is that a mistake, it’s not possible. We are basically emotional beings. When a colleague says “I’m not angry! I’m just determined,” stay tuned. As that individual tries to suppress his or her emotions, they will leak out in other ways.

Once you start to experience corporations and organizations as living systems, populated with living people, you then see that emotions are already playing an integral role in any serious sustainability effort there. Making emotions more explicit can have value. Without making our grief explicit, how can we find the motivation to get involved in efforts to save the 30,000 children who will otherwise die of starvation? Without exploring the anger we feel at the injustice of thousands of infants being born with mercury toxicity, how can we act to change that outcome in our industries and our regulations? Without naming our fear of the consequences of polar ice caps melting, how can we take the actions necessary to create clean and renewable energy sources? And without taking the time to draw forth the joy we feel in celebrating our achievements, how can we have the strength to endure? Emotions exist in all of us; they can provide an important source of initial energy and insight for any action-oriented learning process. It is time to reclaim them.

Emotions also give us feedback on the potential direction of our efforts — or those of our organization. For example, if anger is present, there is a good chance that there is some injustice in the system that needs to be addressed. If fear is present, there is a good chance that we need to raise our awareness of some imbalance in the system. If grief is present, we may have lost or be about to lose something precious. And if joy is present, there is a good chance we’re on the right track. The trick is learning to distinguish the source of the anger, fear, grief, or joy. For example, is fear a justified signal of impending troubles, or an exaggerated personal fear reflected outward?

Our work is to increase our capacity to understand and interpret our emotional systems. The value of coaching often comes in helping people discern the many faces of grief, anger, joy, and fear and seeing what “wants” to happen — how do those emotions link to actions?

Suppose, for example, that you are outraged and angry about a report of those 30,000 children dying of starvation. Your emotions may lead you to open your heart and write a check to Oxfam or some other trustworthy agency. But what can you do, from the vantage point of your life’s work, to make more of a difference — or to prevent such tragedies from occurring in the future?

It will take time and attention to design such an effort. A true commitment might mean leveraging your job; if you are an engineer at an oil company, that will take a certain form; if you are an editor at a nonprofit newsletter, a different form; a marketer at a consumer products firm, still another. It will mean defining your commitment: What is your vision for children? Is it simply to avoid starvation, or are you committed to doing what you can to provide life, food, caring guardians, and education? Since time and capabilities are limited, which children, in which contexts, in which ways, will you work to help? How much effort and time can you realistically put in without infringing on other commitments important to you? Will you be acting alone, or can you marshal the efforts of other people, either in an existing organization or in a group that coalesces for that purpose? Or is there an existing endeavor that you would do better to join?

You want a planet where your kids and all kids can thrive. As your vision for life grows, and as your awareness of current reality deepens, you may feel some despair at the vastness of the gap between the two. What can one person possibly do to make a difference? At the same time, you may also see a compelling need for new, more effective actions. As you increase your commitment to creating a planet where life thrives, you will find that a deepening understanding of your own emotional energy is essential, as is time for quiet reflection. And as your skill, intelligence, and heart for working in these domains grows, so does your capacity to be a wise, compassionate, and effective leader. These qualities will be reflected in the actions you take in service of sustainability, small and large, day to day.

Sara Schley is a founding partner, with Joe Laur, of SEED Systems, a company that applies systems thinking, scientific frameworks, and organizational learning to create sustainable enterprises. In partnership with the Society for Organizational Learning, they established the SoL Sustainability Consortium, where they lead collaborative projects among the members as well as coach individual member projects. This consortium includes members from BP, Ford, Harley, Unilever, UTC, Nike, 7th Generation, and more. Sara was an organizational consultant with the MIT Organizational Learning Center, SoL’s predecessor, from 1992–1997. She also studied with Dr. Karl-Henrik Robért, founder of The Natural Step, and was on the founding steering committee responsible for bringing TNS to the United States.

This article is reprinted with permission from Learning for Sustainability by Peter Senge, Joe Laur, Sara Schley, and Bryan Smith (SoL, 2006).

NEXT STEPS

-

- Develop a capacity for “find out how” in your business. That is, see this as a learning journey where people are encouraged to imagine the company’s future and create it.

- Develop a sustainability vision for yourself, your team, and your business. What is the legacy that you want your company to leave future generations?

- Support and challenge yourself and colleagues to examine and shift mental models regarding your business and its relationship to natural resources.

- Increase your own “ecological literacy”; develop some personal mastery in this domain.

- Share new learning, visions, and attitudes with each other through formal and informal dialogue and conversation.

- Ask the strategic question, “What business am I in?” Answer this from the perspective of what service your products provide. For example at Interface Carpets, they realize they sell warmth, ambience, and comfort, not just carpeting.

- Ask, “How can I provide the services that my business/product delivers in a way that is aligned with the earth’s natural systems?” To answer this question, consider the following sustainable business development guidelines:*

-

- Minimize throughput of energy and materials.

- View all waste as “food” for some other natural or technical process.

- Live on “current income” from solar and other natural resources rather than by consuming the “principle” of those resources.

- Maximize diversity in your business to increase flexibility.

(* adapted from Bill McDonough)

-

- Assess the current reality of your company’s impact via a “take, make, waste” analysis. That is, determine the total amounts of energy and materials that come into your business and which of these leave as products, which as organic wastes, and which as toxic wastes.

- Recognize that a sustainability strategy can focus on both shortand long-term horizons simultaneously. Short-term financial gains made from driving waste out of the business can fund longer-term strategic investments in sustainable products and services designed to meet the demands of tomorrow’s global markets. This is an ongoing journey. Wise business leaders will keep learning and developing.