An organizational and spiritual awakening is currently taking place. On the eve of the new millennium, more and more people are seeking deeper meaning in their work beyond just financial rewards and prestige. The desire to make a difference, to support a worthwhile vision, and to leave the planet better than we found it all contribute to this new urge. Whom we choose to follow, how we lead, and how we com together to address the accelerating change are also shifting.

Organization must pay attention these transitions, because of the radical reduction in the numbers of workers currently available for jobs and the movement into our working ranks of a new generation of employees with totally different values and expectations. If companies want to attract and keep top talent, the old ways of recruiting, rewarding, and leading won’t get us there. A different kind of leadership is required for the future.

Traditional Leadership Models

What are the roots of the leadership models that brought us to this point in organizational development? During the Industrial Revolution, hierarchies were the norm. At that time, businesses depended on the completion of many repetitive tasks in the most efficient way possible. To that end, factories, railroads, mines, and other companies followed a top-down view of leadership, in which those at the top gathered the information, made the decisions, and controlled the power. Those at the bottom—the “hired hands”—were rewarded for conformity and unquestioning obedience. In addition, business moved much more slowly than it does today.

Our approach to preparing new leaders over the last 50 years has sprung from these roots. Leadership training in MBA courses has been based on the case-study method, through which learners study patterns of how others solved their business problems. The assumption has been that if you learn enough about the successful case studies, you will be prepared as a leader—you will be able to go forth, match your new challenges to the case studies of the past, and superimpose a similar solution on the problems of today.

Yet change is accelerating, and we are now in a time when many companies view a traditional education as more of a negative than a positive. They even consider an MBA a detriment, because graduates must unlearn their reliance on the past in order to see new, more complex patterns emerging. Some observers have said that this shift has turned the pyramid of power on its head.

The Beginnings of Servant-Leadership

Servant-leadership is one model that can help turn traditional notions of leadership and organizational structure upside-down. Robert K. Greenleaf came up with the term “servant-leadership” after reading The Journey to the East by Hermann Hesse (reissued by The Robert K. Greenleaf Center, 1991). In this story, Leo, a cheerful, nurturing servant, supports a group of travelers on a long and difficult journey. His sustaining spirit helps keep the group’s purpose clear and morale high until, one day, Leo disappears. Soon after, the travelers disperse. Years later, the storyteller comes upon a spiritual order and discovers that Leo is actually the group’s highly respected titular head. Yet by serving the travelers rather than trying to lead them, he had helped ensure their survival and bolstered their sense of shared commitment. This story gave Greenleaf insight into a new way to perceive leadership.

Greenleaf was reading this book because he was helping university leaders deal with the student unrest of the 1970s, a challenge unlike any they had faced before. In the spirit of trying to understand the roots of the conflict, Greenleaf put himself in the students’ shoes and began to study what interested them. It was from this reflection that the term “servant-leadership” first came to him. To Greenleaf, the phrase represented a transformation in the meaning of leadership.

Servant-leadership stands in sharp contrast to the typical American definition of the leader as a stand-alone hero, usually white and male. As a result of this false picture of what defines a leader, we celebrate and reward the wrong things. In movies, for example, we all love to see the “good guys” take on the “bad guys” and win. The blockbuster “Lethal Weapon” movies are a take-off on this myth and represent a metaphor for many of our organizations. Our movie “heroes” (or leaders) act quickly and decisively, blowing up buildings and wrecking cars and planes in highdrama chases.

Although they always win (annihilating or capturing the bad guys), they leave behind a trail of blood and destruction.

This appetite for high-drama can fool us into believing that we can depend on one or two “super people” to solve our organizational crises. Even in impressive corporate turnarounds, we tend to look for the hero who single-handedly “saved the day.” We long for a “savior” to fix the messes that we all have had a part in creating. But this myth causes us to lose sight of all those in the background who provided valuable support to the single hero.

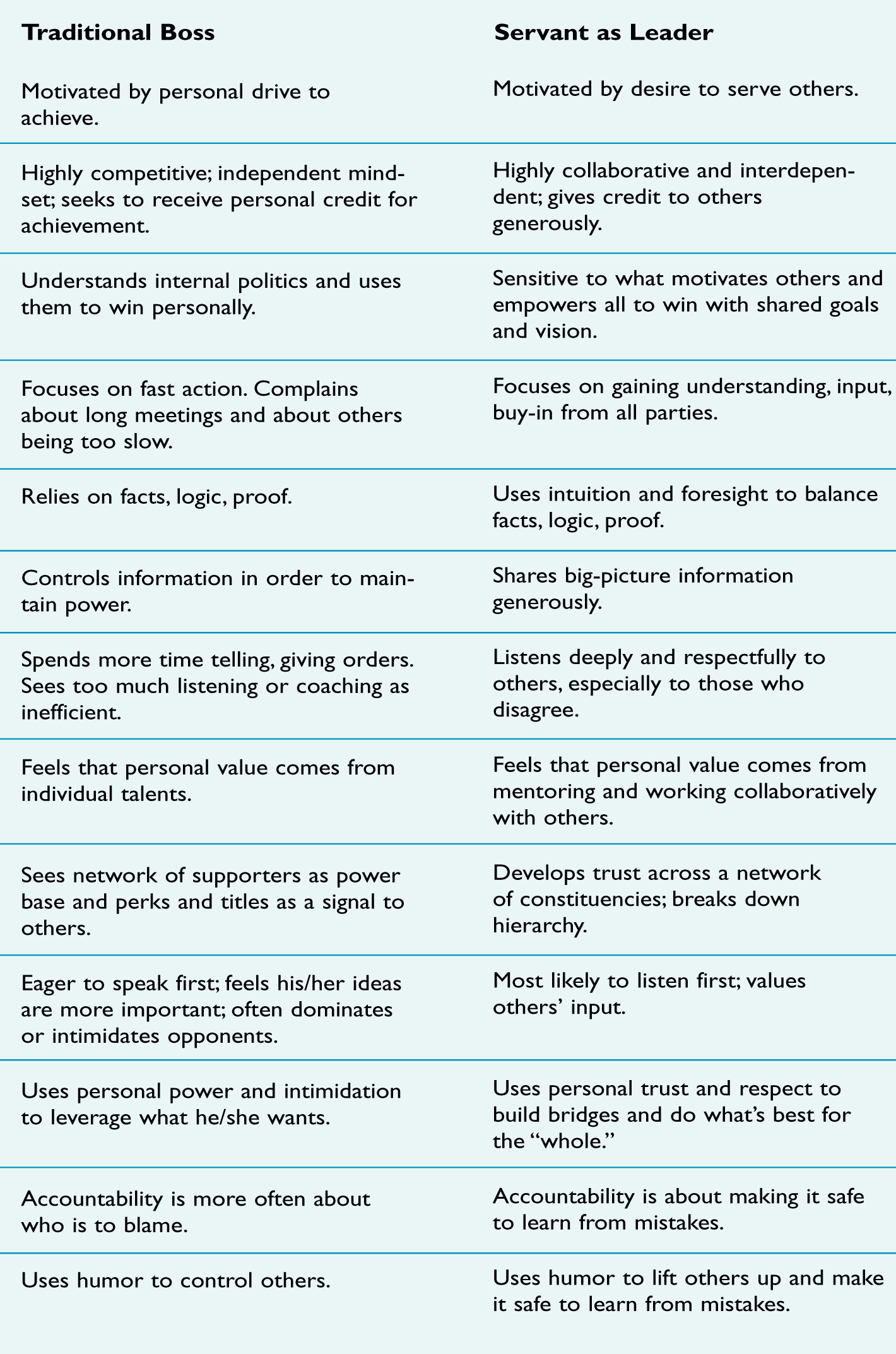

Seeing the leader as servant, however, puts the emphasis on very different qualities (see “A New Kind of Leadership” on p. 3). Servant-leadership is not about a personal quest for power, prestige, or material rewards. Instead, from this perspective, leadership begins with a true motivation to serve others. Rather than controlling or wielding power, the servant-leader works to build a solid foundation of shared goals by (1) listening deeply to understand the needs and concerns of others; (2) working thoughtfully to help build a creative consensus; and (3) honoring the paradox of polarized parties and working to create “third right answers” that rise above the compromise of “we/they” negotiations. The focus of servant-leadership is on sharing information, building a common vision, self-management, high levels of interdependence, learning from mistakes, encouraging creative input from every team member, and questioning present assumptions and mental models.

How Servant-Leadership Serves Organizations

Servant-leadership is a powerful methodology for organizational learning because it offers new ways to capitalize on the knowledge and wisdom of all employees, not just those “at the top.” Through this different form of leadership, big-picture information and business strategies are shared broadly throughout the company. By understanding basic assumptions and background information on issues or decisions, everyone can add something of value to the discussion because everyone possesses the basic tools needed to make meaningful contributions. Such tools and information are traditionally reserved for upper management, but sharing them brings deeper meaning to each job and empowers each person to participate more in effective decision-making and creative problem-solving. Individuals thus grow from being mere hired hands into having fully engaged minds and hearts.

Our movie “heroes” (or leaders) act quickly and decisively, blowing up buildings and wrecking cars and planes in high-drama chases. Although they always win (annihilating or capturing the bad guys), they leave behind a trail of blood and destruction.

This approach constitutes true empowerment, which significantly increases job satisfaction and engages far more brain power from each employee. It also eliminates the “that’s not my job” syndrome, as each person, seeing the impact he or she has on the whole, becomes eager to do whatever it takes to achieve the collective vision. Servant-leadership therefore challenges some basic terms in our management vocabulary; expressions such as “subordinates,” “my people,” “staff (versus “line”), “overhead” (referring to people), “direct reports,” “manpower” all become less accurate or useful. Even phrases such as “driving decision-making down into the ranks” betray a deep misunderstanding of the concept of empowerment. Do we believe that those below are resistant to change or less intelligent than others? Why must we drive or push decisions down? Something vital is missing from this way of thinking—deep respect and mentoring, a desire to lift others to their fullest potential, and the humility to understand that the work of one person can rarely match that of an aligned team.

Phil Jackson, former coach of the world champion Chicago Bulls basketball team, described this notion well in his book Sacred Hoops (Hyperion, 1995). He wrote, “Good teams become great ones when the members trust each other enough to surrender the ‘me’ for the ‘we.’As [retired professional basketball player] Bill Cartwright puts it: ‘A great basketball team will have trust. I’ve seen teams in this league where the players won’t pass to a guy because they don’t think he is going to catch the ball. But a great basketball team will throw the ball to everyone. If a guy drops it or bobbles it out of bounds, the next time they’ll throw it to him again. And because of their confidence in him, he will have confidence. That’s how you grow.’” Phil Jackson drew much of the inspiration for his style of coaching—which is clearly servant-leadership—from Zen, Christianity, and the Native American tradition. He created a sacred space for the team to gather, bond, process, and learn from mistakes.

A servant-leader is also keenly aware of a much wider circle of stakeholders than just those internal to the organization. Ray Anderson, chairman and CEO of Interface, one of the largest international commercial carpet wholesalers, has challenged his company to join him in leading what he calls the “second Industrial Revolution.” He defines this new paradigm as one that finds sustainable ways to do business that respect the finiteness of natural resources. His vision, supported by his valued employees, is to never again sell a square yard of carpet. Instead, they seek to lease carpeting and then find ways to achieve 100-percent recycling.

A NEW KIND OF LEADERSHIP

A servant-leader thus does not duck behind the letter of the law but asks, “What is the right thing for us to do to best serve all stakeholders?” He or she defines profit beyond financial gain to include meaningful work, environmental responsibility, and quality of life for all involved. To quote Robert Greenleaf, “The best test, and difficult to administer, is: do those served grow as persons; do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants? And, what is the effect on the least privileged in society; will each benefit, or at least not be further deprived?”

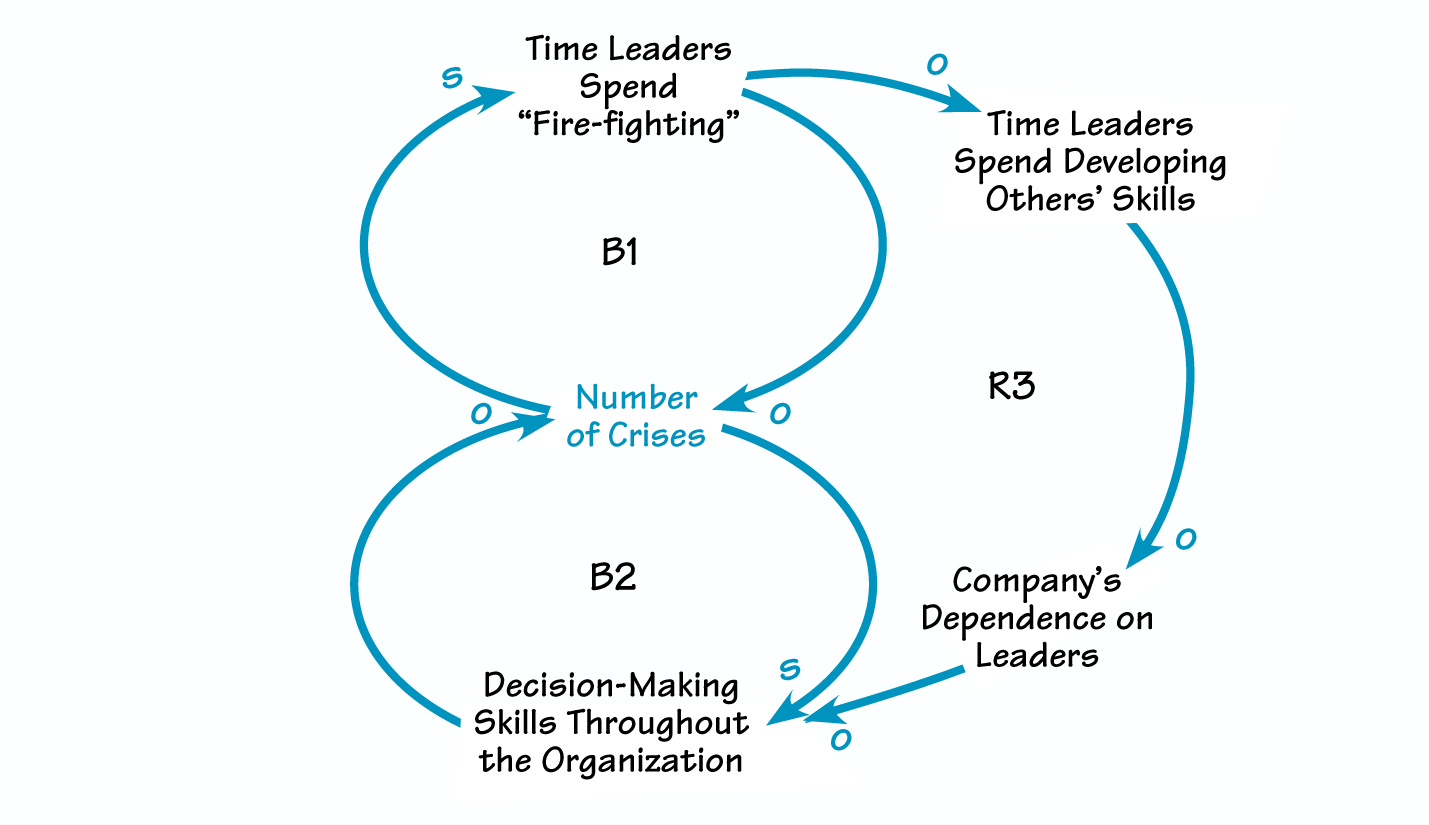

Supervisors often believe that they don’t have time to make a longterm investment in people (see “Addiction to Fire-fighting”). When an individual’s primary focus is on doing everything faster, she becomes addicted to the constant rush of adrenaline. To feed this craving, the person neglects proactive tasks such as coaching, mentoring, planning ahead, and quiet reflection to learn from mistakes. Instead, the brain sees only more problems—reasons to stay reactive and highly charged. Servant-leaders spend far less time in crisis management or fire fighting than do traditional managers. Instead, they use crises as opportunities to coach others and collectively learn from mistakes.

ADDICTION OF FIRE-FIGHTING

As the number of organizational “fires” increases, leaders spend more and more time “fire-fighting,” which, in the short-term, reduces the number of crises (B1). However, the fundamental solution is to build decision-making skills in others (B2). By focusing on crisis management rather than on staff development, supervisors increase the company’s dependence on their own expertise and actually erode the level of competency throughout the organization (R3).

The Power of Internal Motivation and Paradox

So what does it take to become a servant-leader? The most important quality is a deep, internal drive to contribute to a collective result or vision. Very often a servant-leader purposely refuses to accept the perks of the position and takes a relatively low salary because another shared goal may have more value. For example, Southwest Airlines chairman Herb Kelleher has long been referred to as the most underpaid CEO in the industry. Herb was the first to work without pay when SWA faced a serious financial threat. In asking the pilot’s union to agree to freeze their wages for five years, he showed his commitment by freezing his own wages as well.

Big salaries and attractive perks are clearly not the main motivators for Southwest’s leadership team; the company’s top leaders are paid well below the industry average. Rather, they stay because they are making history together. Their vision is a noble one—to provide meaningful careers to their employees and the freedom to fly to many Americans who otherwise could not afford the convenience of air travel. SWA’s leaders love to take on major competitors and win. Beyond that, each finds fulfillment in developing talent all around him or her. Servant-leadership has become a core way of being within Southwest Airlines.

A second quality of servant-leaders is an awareness of paradox. Paradox involves two aspects: the understanding that there is usually another side to every story, and the fact that most situations contain an opposite and balancing truth (see “The Structure of Paradox: Managing Interdependent Opposites,” by Philip Ramsey, The Systems ThinkerV8N9). Here are some of the paradoxes that servant-leadership illuminates:

- We can lead more effectively by serving others.

- We can arrive at better answers by learning to ask deeper questions and by involving more people in the process.

- We can build strength and unity by valuing differences.

- We can improve quality by making mistakes, as long as we also create a safe environment in which we can learn from experience.

- Fewer words (such as a brief story or metaphor) can provide greater understanding than a long speech. A servant-leader knows to delve into what is not being said or what is being overlooked, especially when solutions come too quickly or with too easy a consensus.

A Time for Transformation

We are moving away from a time when a strong hierarchy worked for our organizations. In the past, we gauged results in a far more limited way than we do today—financial and other material gain, power, and prestige were viewed as true measures of success. Other, more complex measures, such as the impact of our businesses on society, families, and the environment, have not been part of our accounting systems. Yet now, as we move into the Information Age and a new millennium, we’ve come to recognize the limitations of the traditional “bottom line.”

In the past, we gauged results in a far more limited way than we do today . . .Yet now, as we move into the Information Age and a new millennium, we’ve come to recognize the limitations of the traditional “bottom line.”

A servant-leadership approach can help us overcome these limitations and accomplish a true and lasting transformation within our organizations (see “Practicing Servant-Leadership”). To be sure, as we envision the many peaks and valleys before us in undertaking this journey, we sometimes may feel that we are alone. But we are not alone—many others are headed in the same direction. For instance, in Fortune magazine’s recent listing of the 100 best companies to work for in America, three of the top four follow the principles of servant-leadership: Synovus Financial (number 1), TDIndustries (number 2), and Southwest Airlines (number 4). In addition to providing a nurturing and inspiring work environment, each of these businesses is recognized as a leader in its industry.

On a personal level, as many of us begin to come to terms with our own mortality, our desire to leave a legacy grows. “What can I contribute that will continue long after I am gone?” Some yearn to have their names emblazoned on a building or some other form of ego recognition. Servant-leaders find fulfillment in the deeper joy of lifting others to new levels of possibility, an outcome that goes far beyond what one person could accomplish alone. The magical synergy that results when egos are put aside, vision is shared, and a true learning organization takes root is something that brings incredible joy, satisfaction, and results to the participants and their organizations. For, as Margaret Mead put it, “Never doubt the power of a small group of committed individuals to change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” The true heroes of the new millennium will be servant-leaders, quietly working out of the spotlight to transform our world.

PRACTICING SEVANT-LEADERSHIP

- Listen Without Judgment. When a team member comes to you with a concern, listen first to understand. Listen for feelings as well as for facts. Before giving advice or solutions, repeat back what you thought you heard, and state your understanding of the person’s feelings. Then ask how you can help. Did the individual just need a sounding board, or would he or she like you to help brainstorm solutions?

- Be Authentic . Admit mistakes openly. At the end of meetings, discuss what went well during the week and what needs to change. Be open and accountable to others for your role in the things that weren’t successful.

- Build Community. Show appreciation to those who work with you. A handwritten thank-you note for a job well done means a lot. Also, find ways to thank team members for everyday, routine work that is often taken for granted.

- Share Power. Ask those you supervise or team with, “What decisions am I making or actions am I taking that could be improved if I had more information or input from the team?” Plan to incorporate this feedback into your decision-making process.

- Develop People . Take time each week to develop others to grow into higher levels of leadership. Give them opportunities to attend meetings that they would not usually be invited to. Find projects that you can co-lead and coach the others as you work together.

Ann McGee-Cooper, Ed. D., is founder of Ann McGeeCooper & Associates, a team of futurists who specialize in creative solutions and the politics of change. For the past 25 years, she and her team have worked to develop servant-leaders. Duane Trammell, M. Ed., is managing partner of Ann McGee-Cooper & Associates and co-author of the group’s servant-leadership curriculum.

Editorial support for this article was provided by Kellie Warman O’Reilly and Janice Molloy.

Suggested Further Reading

Greenleaf, Robert K. The Servant as Leader. The Robert K. Greenleaf Center, 1982.

Greenleaf, Robert K., Don T. Frick (editor), and Larry C. Spears (editor). On Becoming a Servant-Leader. Jossey-Bass, 1996.

Greenleaf, Robert K., Larry C. Spears (editor), and Peter B. Vaill. The Power of Servant-Leadership. BerrettKoehler, 1998.

Jackson, Phil, and Hugh Delehanty. Sacred Hoops: Spiritual Lessons of a Hardwood Warrior. Hyperion, 1995.

Melrose, Ken. Making the Grass Greener on Your Side: A CEO’s Journey to Leading by Serving. Berrett-Koehler, 1995.