It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. . . .” So begins Charles Dickens’s classic novel A Tale of Two Cities. Unfortunately, in the “Success to the Successful” archetype, the best and the worst of times are often hard-wired into the structure, so that it is always the best of times for one alternative and the worst of times for the other. To understand this “tale of two loops,” let’s consider a common—and timely—example.

Not-So-New New Year’s Resolutions

As we start the new year, many of us take the time to jot down some New Year’s resolutions. If you are like most people, you may find that a few of the items on your list were also there last year—and the year before and the year before that. Why can’t we make the changes that we have “resolved” to make and that, in most cases, we have the power to accomplish?

One easy response may be that we don’t really want to do some of the things that we commit to doing. We come up with “politically correct” items like eating less red meat and more organic vegetables so that we can dutifully produce our list when someone asks us, “Are you making any New Year’s resolutions?” Let’s remove those gratuitous pronouncements from consideration and look at the changes in behavior that we really do want to accomplish, such as losing weight. Are we just too lazy or weak-willed to fulfill our commitments? Before we berate ourselves yet again, we may want to examine our situation from a systemic perspective. The “Success to the Successful” archetype can help us understand the structural forces that are preventing us from carrying out our well-intentioned resolutions.

Organizational Law of Inertia

The “Success to the Successful” structure is largely driven by inertia. In physics, the principle of inertia means that, barring outside influences, an object that is in motion will tend to stay in motion; an object that is at rest will generally stay at rest. In the case of “Success to the Successful,” the person or project that initially succeeds will continue to succeed. On the other hand, the person or project that, for whatever reason, gets a late start will tend to fail.

Why can’t we make the changes that we have “resolved” to make and that, in most cases, we have the power to accomplish?

So, it’s easier to maintain existing habits (such as eating more and exercising less than we should) than to establish new ones (like sticking to a diet and walking at lunch time). The structure of our organizational systems—and our own mindsets—contributes to the forces that produce these predictable results. To better understand how this dynamic works, let’s take a detailed look at the behavior over time of this archetype (see “Initial Dynamics of ‘Success to the Successful’”).

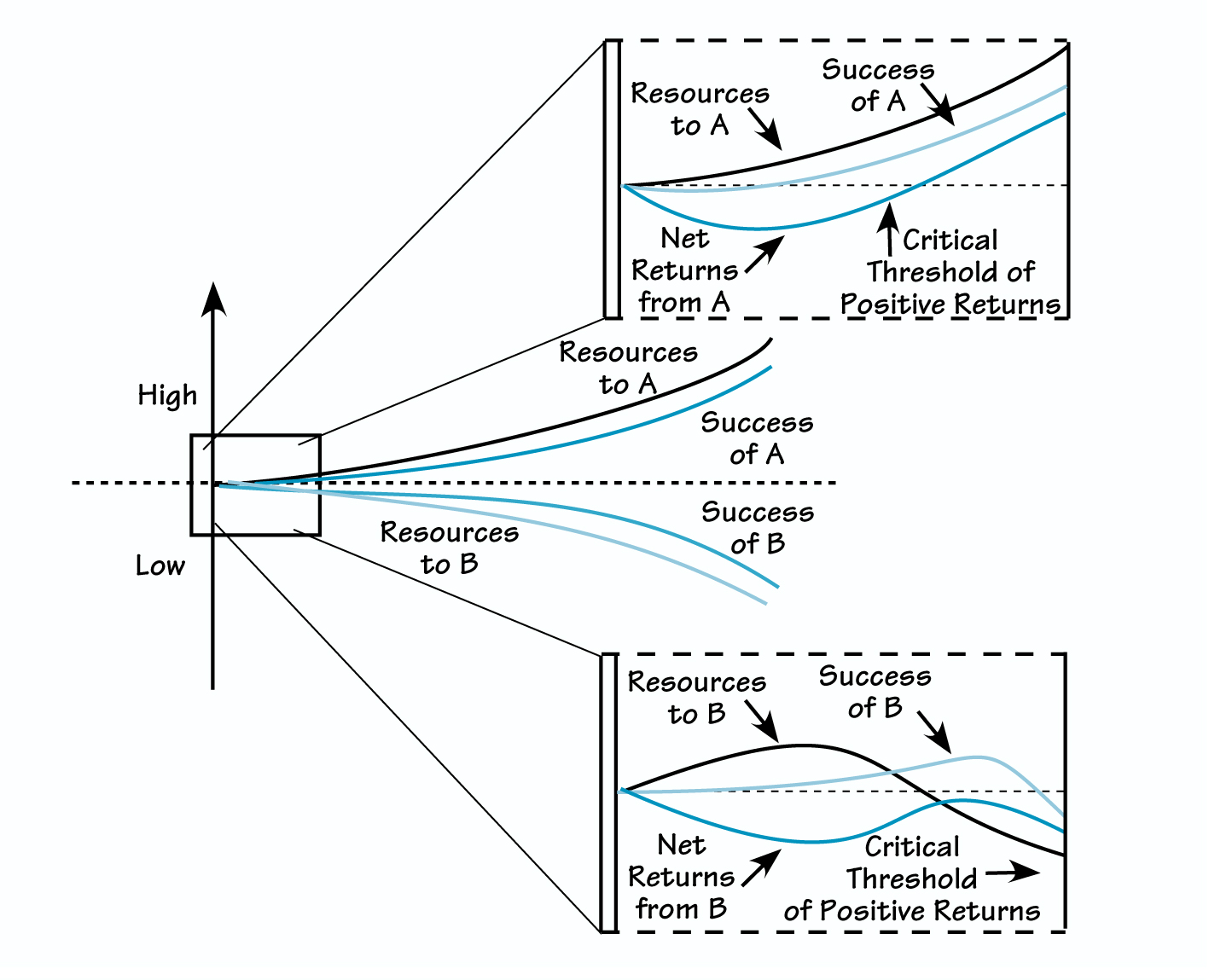

The center of the diagram illustrates the overall results of this archetype: As the resources dedicated to A and A’s success both increase, the resources invested in B and, in turn B’s success decline. The insets above and below this graph provide a more detailed look at the initial dynamics that play a critical role in this longterm outcome. We devote resources to A (which represents the original or the more favored person, product, or activity) for some time with no visible success; therefore, in the beginning, the net returns for A are low or even negative. Sustained investment, however, eventually leads to A’s success. The key here is that, if we sustain our investment in A beyond a critical point, A begins to generate positive returns. Beyond this critical threshold of positive returns, A’s success is likely to be self-sustaining, because continued investment brings ongoing positive net returns.

In the case of B, we start by making the same initial investments as for A but, for whatever reasons (poor timing, external forces, the effects of learning curves, etc.), B takes longer than A to become successful. In many cases, the reason for A’s comparative success is that it had a head start in and is already beyond the critical threshold of positive returns. Thus, B’s net returns stay low or negative longer than A’s, and B begins to look less attractive as an alternative. As a result, we decide to invest less and less in B, which delays B’s achievement of success even further. At a certain point, we may even begin to take away resources, such as people and equipment, because we don’t want to waste them on a “lost cause.” In turn, B’s performance only declines further. We eventually conclude that B is a failed experiment and abandon it.

In the case of our New Year’s resolutions, the success of our old habits in giving us satisfaction makes it difficult for our new efforts to produce equally compelling benefits in the first few months. So, we may pat ourselves on the back for trying to drop a few pounds, mutter something to the effect of “It just wasn’t meant to be,” and comfort ourselves with another hot fudge sundae.

Overcoming the “Survival of the Fittest” Mentality

In a way, the “Success to the Successful” archetype helps show why something that looks like a fair and equal setup is often rigged to favor one party over another. The imbalance can stem from some random external event, a personal bias, or simply the momentum of the first party’s current success. Unfortunately, many management decisions are based on a “survival of the fittest” mentality that ignores the effects of this initial imbalance. As a result, we may not end up with a particular person, product, or activity because it is the “fittest,” but rather because it was either the first or the most widely available option. In this way, we may ultimately accept an inferior outcome over what could have been—and possibly ruin a career or two along the way.

We may continue to use inferior methods because we are familiar with them.

In order to achieve the best possible outcome, we need to be sure that we gave the second alternative a fair shake instead of dooming it to failure from the start. This is particularly important when A is already well established, because any comparisons of B to A tend to make B look less appealing. In this case, comparing A and B would be like judging the performance of a five-year-old child against that of a ten-year-old and concluding that the younger child is inferior and not worth further investments. But, in actuality, the five-yearold may be much better at accomplishing the task than the older child ever was at that same age. Without separating our evaluation of B’s performance from A’s, we may end up sticking with current levels of competency at the expense of developing competency for the future.

INITIAL DYNAMICS OF 'SUCCESS TO THE SUCCESSFUL'

The center of the diagram illustrates the overall results of this archetype: As the resources dedicated to A and A’s success both increase, the resources invested in B and, in turn, B’s success decline. The insets above and below this graph provide a more detailed look at the initial dynamics that play a critical role in this long-term outcome.

People and organizations often suffer from this “competency trap” because, in the short run, it seems to make more sense to invest in something that is already successful than in something new and untried. The downside of this tendency is that we may unwittingly continue to use adequate but inferior tools or methods simply because we are familiar with them. This inclination can have dire consequences when we fail to invest in newly emerging competencies (e.g., when IBM was slow to recognize the importance of personal computers).

To break out of a competency trap, we must clarify our goals for the new product or initiative and identify the resources needed to achieve those objectives. We then must examine how the success of the current effort may systematically undermine support for the new initiative, and find a way to decouple the two.

It Was the Best of Times . . . Initially

“Success to the Successful” raises questions about what drives success in certain situations. It also shows how, if we are not clear about the overall result that we are trying to achieve, the differences in initial conditions alone can have powerful long-term effects on the outcome. Finally, this archetype illustrates how we can persuade ourselves to stay in old lines of business or outmoded ways of doing things simply because we are already good at them. To escape from this trap, we need to look beyond what works and clarify what we actually want in the longer term. We may then be in a better position to keep some of our resolutions this year—and next.

Daniel H. Kim, PhD, is publisher of The Systems Thinker and a member of the governing council of the Society for Organizational Learning.