Roger and his wife June had been struggling with differing views about how to bring up their children. Recently, Roger attended a program about holding productive conversations around difficult issues at work. During these sessions, he began to see a pattern in his communications with June. It became obvious that they fought repeatedly about the same concerns and never inquired into each other’s views. He was excited about practicing his new inquiry skills at home.

Family life, like organizational life, is filled with challenges and complexity. We begin family life with great hopes of love and warmth. We dream about learning and growing as we build our lives together. Yet for numerous families, and friends living together as families, learning together seems rare. Too often, people are stymied when faced with the complexity and difficulty of actual family living.

Part of the reason for this difficulty is that couples and single parents often lack the perspective, skills, and tools for mastering the increasing rate of life changes. One essential perspective that we often miss is that our families are complex systems and, as such, are more than a group of individuals. Even divorced partners who are now co-parenting find that family dynamics persist. Any kind of shift for one member — such as a new job or a bad grade on an exam — has an impact on the family as a whole.

In the face of life’s inevitable changes and the complexity of our relationships, how can we thrive even when family dynamics become challenging? How can we pay attention to our difficulties in such a way that our relationships grow together, not fall apart? We believe that the five disciplines can help to create a learning family at home as much as they can build a learning organization at work.

Two Essential Capabilities

Family life is one setting where people can become more skillful at navigating life transitions in order to fulfill their aspirations. To do so, they need to feel a sense of safety, believe that what they want is important, and trust that the hard times, including painful feelings and difficult exchanges, can actually be sources of growth and healing. Two essential capabilities help families cultivate these experiences: 1) living in a creative orientation and 2) building a powerful context or “container” for speaking and listening deeply. Let’s take a closer look at these two capabilities.

Living in a Creative Orientation. Many families dwell in what author Robert Fritz calls a “reactive orientation.” They feel overwhelmed by forces that they believe are beyond their control, such as lack of time for family and friends, work and financial pressures, lack of support, and violence in the schools and media. These pressures tend to pull families apart even when members wish to be closer to each other. In addition, family life has its own inherent challenges such as working out differences between spouses, parenting children through different ages, and facing critical life passages such as birth and death. In a reactive mode, people start to blame themselves or others for their difficulties, or they simply feel helpless.

Fritz contrasts this with the concept of a “creative orientation.” In a creative orientation, we deepen our understanding of ourselves, we turn toward the possible, and we look for our own contribution to a current situation. In this way, we restore the sense of purpose and efficacy that we forget when we are in a reactive mode. Through our families, we also have the opportunity to deepen our understanding of others, their values, and their dreams. We learn to give what’s needed and to hold fast to each other’s aspirations, even when despair sets in. Together we learn how to stop blaming each other; clarify the values, aspirations, and talents that unite us; and affirm the kind of contribution we want to make to the outside world.

Building a Container. Building a container involves developing the capacity to listen and speak deeply together. In discussing the concept of a container, Bill Isaacs, author and organizational consultant, suggests the image of a sturdy vessel that holds its bubbling hot contents without cracking, allowing them to transform into something of profound value. Too often, our families are the last people we turn to when we want to be heard, because of the intensity of emotions involved in intimate relationships. However, we can change that through carefully creating this kind of a container. A strong container can help us bring stability and resilience to life’s difficult situations instead of rushing in to fix them prematurely or running away from them. To build a container:

- Develop ground rules for engaging in difficult conversations.

- Establish uninterrupted times and places to explore and resolve tensions.

- Meet the challenges you and others are facing with commitment, courage, and curiosity.

- Slow down and reconnect with your heart.

- Respect other family members’ feelings, and seek to understand the thinking that leads them to feel the way they do.

- Agree on how to behave with each other on a daily basis.

- Trust that difficulties, when handled well, can lead to genuine growth.

The Five Disciplines at Home

We believe that the five disciplines point to actions that families can take to build such a container and to create fulfilling and loving lives together. A virtuous cycle can unfold in which applying the five disciplines enhances our ability to live in a creative orientation and build our containers, which in turn strengthens our ability to practice the five disciplines. Personal Mastery. In the early years of Innovation Associates’ Leadership and Mastery Program, participants’ spouses were encouraged to attend the training in recognition that a leader’s professional vision can be achieved only within the context of his or her personal aspirations. As an individual in a relationship, you have a responsibility to both yourself and your family to fulfill your potential. You also have a responsibility to help your partner and children realize their potential.

We suggest four ways to explore the path of personal mastery within your family:

The five disciplines point to actions that families can take to build such a container and to create fulfilling and loving lives together.

1. Make compromises and avoid sacrifices. Psychologist Nathaniel Branden suggests that compromising means being willing to change what you do in service of another. It is an essential aspect of family life. By contrast, sacrifice means trying to change who you fundamentally are to satisfy another, which is ultimately a disservice to both parties. Learning who you are and knowing what you really care about enable you to make compromises and avoid sacrifices.

2. Appreciate others for what they contribute to you and to the world around them. A relationship counselor we know asks each clients to list 25 things in their lives for which they are grateful. Her premise is that you cannot create joyful intimacy without appreciating all the gifts you already have. Being grateful for your life and for each family member’s place in it helps you reconnect with how unique and valuable they are. For example, we find it helpful to reflect with each other at the end of every day on what has enriched us, and what we appreciate about each other, ourselves, and our relationship.

3. Adopt the perspective that family challenges can help us grow. It’s easy to get distracted by the idea that family members are being a pain in the neck and are keeping us from moving toward our vision. However, psychologist Harville Hendrix observes that we attract a mate who is different from ourselves in precisely the ways in which we need to grow, and that our children’s behavior presents an opportunity for us to parent in just those ways that we were not parented ourselves. The key is to recognize relationship challenges as stemming from our own innate desire to heal and grow, rather than from faults in other people.

4. Remember that we are all more than the sum of our successes and failures. Focusing only on successes can be difficult for everyone in the family. It can be difficult for the successful ones because they may feel that people care about them only when things are going well, and difficult for others because failures then become a source of shame. Supporting a partner or child through failures entails seeing his or her good qualities under all circumstances. A learning family can learn much from failure and can come to celebrate successes in inclusive ways.

Shared Visioning. “What are we about as a family? What do we envision for ourselves this year . . . five years from now? What do we deeply care about?” Our visions and dreams can easily get lost in the everyday pressures of errands, to-do lists, and piles of laundry. It’s hard to envision making a difference when you can’t find a pair of matching socks.

Shared visioning is a conversation that helps people open their hearts to hearing each other’s deepest wishes and loves—their hearts’ desires. As children get older, shared visioning can help a family see what they have in common and how they can inspire each other to pursue their desires and create more of what they want in life. When people open their conversation to visioning, they can recall the hopes, dreams, values, and images that brought them together. Sharing these moments is particularly powerful during difficult times because these memories restore the energy of loving connection:

“Now I remember, that is why we are together!”

In visioning together, we explore what we can do together and how we can be together. We imagine how to spend our time together, how we want to be involved in our community, where we want to live, how we want to socialize, and where we want to travel. We can share our visions yearly, monthly, or daily. For example, Mark and Ellen take a walk together each week, during which each one reflects on the lessons of the past week and identifies a vision for the coming one. They then share their visions with each other, allowing both partners to feel support in the growth and learning they are embarking on. The ritual itself becomes a strong container of trust and respect that increases their ability to create what they want in their lives individually and as a partnership.

Mental Models. The discipline of mental models helps us gain a greater understanding of how our minds work. With careful observation, we begin to see that our beliefs have an impact on our perceptions, which in turn influence our actions, and then our reality. Our mental models serve us when they enable us to focus on what we want. However, they are always simplified, and therefore incomplete, views of reality that can hurt us when we miss something important or when the conditions under which we created them change.

Family life provides a great setting to develop skill in surfacing and testing our beliefs, revising them when necessary (see “Surfacing Mental Models of Family Life”). Not only do families offer ample opportunities to explore differing perceptions, but also the love on which they are based encourages people to take risks in exploring these differences and misunderstandings. Home is a place to experience humility and to learn.

The tools of the discipline of mental models, such as the ladder of inference, balancing advocacy and inquiry, and the left-hand column, can be useful when tried out at home. For example, recognizing that there might be a difference between how you experience your partner’s or child’s behavior and what he or she intends can help you accept that certain actions are not intended to hurt you (or make you mad or jealous), no matter how hurtful they might feel. This assumption can lead you to ask several questions when you are experiencing conflict:

SURFACING MENTAL MODELS OF FAMILY LIFE

The division of labor between partners is another example where we can engage powerful mental models for learning. Many of us grew up in an era in which the man of the family was the sole “breadwinner,” and the woman took responsibility for the household. Conflict may arise when one partner maintains traditional mental models about gender roles while the other is more modern in his or her thinking. These differences can be explosive, because they may include deep beliefs about what it means to be cared for and who has the power in the household and in the world. Couples must be able to skillfully engage their assumptions about gender roles and reshape them to meet their own personal aspirations.

- What pressures is my partner or child facing?

- What might he or she be intending to accomplish?

- How might my behavior appear to him or her?

- How can we share our respective intentions and learn about the impact we have on each other?

As you consider these questions, you might find yourself growing calmer. Then you can raise your frustration in such a way that the other party is more likely to listen to you with interest and speak with compassion. For example, Brad would sometimes leave his breakfast dishes in the sink on his way out the door, assuming that he would just do them later. However, Michelle perceived the dirty dishes as a chore that she was obligated to do. When they discussed the issue, she learned that he did not intend for her to do his dishes. At the same time, he learned that, because her office was at home, the dishes were an imposition on her space. With this new understanding, both were able to change: Brad usually did not leave his dishes in the sink out of respect for Michelle’s work space, and Michelle was more willing to do his dishes occasionally, knowing that she had a choice.

Another helpful tool is to use the ladder of inference to provide feedback. This approach consists of a series of statements. The first describes observable behavior; it begins with “When you do or say [the observable data].” The statement then continues with “I feel [a particular feeling, such as angry, hurt, jealous].” The feedback continues with “I think [or the story I tell myself is],” which explains my assumption based on that observation and feeling. It concludes with “What I want is ____,” and makes a specific request of the other person. Adhering to this structure, however clumsy at first, can open a genuine dialogue.

For example, Larry and Aisha were returning from a party where Aisha had felt ignored by him. Her initial reaction was to want to tell him, “You abandoned me, just like you always do at parties, and I’m sick and tired of being ignored when we go out.” Instead she said, “When you spent an hour looking at Joe’s Australia photos and didn’t invite me to join you [data], I felt hurt and angry [feeling]. I think you were ignoring me [interpretation]. I want to figure out with you a way we can enjoy parties together [request].”

BRINGING THE FIVE DISCIPLINES HOME

Team Learning. Meaningful conversation takes time, skill, and intention. Weeks, even months, can go by without a family’s carving out the time to sit and simply explore what is going on with its members. If there are tensions between family members, it becomes even easier to postpone “family council” time. Yet, gathering regularly to listen to each other may defuse tensions before they build to a crisis, help the family to identify issues that people are grappling with, or simply offer a time for parents and children to be together and listen to each other’s thoughts and concerns. To create a “learning conversation,” set aside time and find a private space. Then identify some guidelines and a purpose. Even for two people, some of the following guidelines may help shape a surprisingly rich and gratifying conversation:

- Be fully present.

- Be open-minded.

- Listen, listen even more deeply, and then respond.

- Acknowledge the other person’s feelings and reality as true for him or her.

- Speak from your heart instead of from your head. Try breathing slowly, and notice how you are feeling.

- , “Lean into” discomfort. Discomfort is a spark of enlivening energy that is a clue that something can be learned here. “Leaning in” suggests receiving that tension with a quality of alert inquiry.

Team learning offers a way for people to open themselves to learning together. This is a time to practice listening for insight, for something fresh, for a way to reach below our familiar everyday clamor to the surprising wisdom that we carry inside. By practicing team learning, we can listen to one another with a renewed interest and focus.

A learning conversation can be a good time to revisit our vision of family and remind each other of what our family stands for or what we are grateful for. For example, one family gathers after their Thanksgiving meal to ask the question, “What are you thankful for this year?” Each person then has 3-5 minutes of uninterrupted air time as everyone else listens quietly. Then, they reflect together on what they heard.

Bringing the five disciplines home involves identifying and changing well-entrenched patterns of behavior, which can be both rewarding and painful.

Systems Thinking. Systems thinking encourages us to see our family and our role in it in a new light. Every family is a system. When you and other family members fall into typical, ongoing struggles, consider how your behavior is likely to affect theirs and vice versa. After all, you are deeply connected, although in moments of conflict, you might want to deny that fact!

We use two simple tools to help us out of binds: interaction maps and the “Accidental Adversaries” archetype. Interaction maps were developed by Action Design to show how two parties become locked in a vicious cycle by thinking and acting in particular ways. Party A thinks something negative about Party B, which leads Party A to act in either a defensive or an aggressive manner toward Party B. As a result, Party B develops negative thoughts about A, acts out toward A, and reinforces A’s negative thinking. The result is a vicious cycle.

The parties can break this dynamic first by noticing its existence, then by testing the mental models they have of each other, and finally by developing more effective ways of behaving in support of their more complete understanding of the other person’s reality. For example, Rachel thought her partner Carol was too close to her parents and asked her to limit her weekly phone conversations with them. This led Carol to think that Rachel was jealous of her relationship with her parents, prompting her to defend them. Her impassioned defense, in turn, reinforced Rachel’s belief that Carol was too close to her folks. When Rachel and Carol recognized this dynamic, they were able to test their mental models. They discovered that Carol felt pressured by her parents’ insistence on regular weekly contact. When she understood Carol’s position, Rachel was able to relax her own concerns and actually share some of the responsibility for maintaining contact with Carol’s parents.

Many family members become “accidental adversaries”; that is, they possess an enormous potential to cooperate with and serve each other, but tend to end up in conflict because each is subconsciously trying to address a personal hurt, fear, or discomfort. For example, when Bill believes that he will not get something he wants, he becomes aggressive and insists that he has to have it. This behavior gets him what he wants in the short run. However, Joan then becomes concerned that she will not be able to achieve what is important to her. She withdraws from Bill, which makes him feel that he can’t rely on her to support him. For that reason, he finds himself being even more aggressive the next time he thinks he won’t get what he wants. To break out of this negative pattern of behavior, both Bill and Joan need to reaffirm their commitment to supporting each other in achieving their individual and shared visions. Then they can identify their individual needs and reflect together on how they can both help each other meet those needs in ways that don’t make life more difficult for the other person.

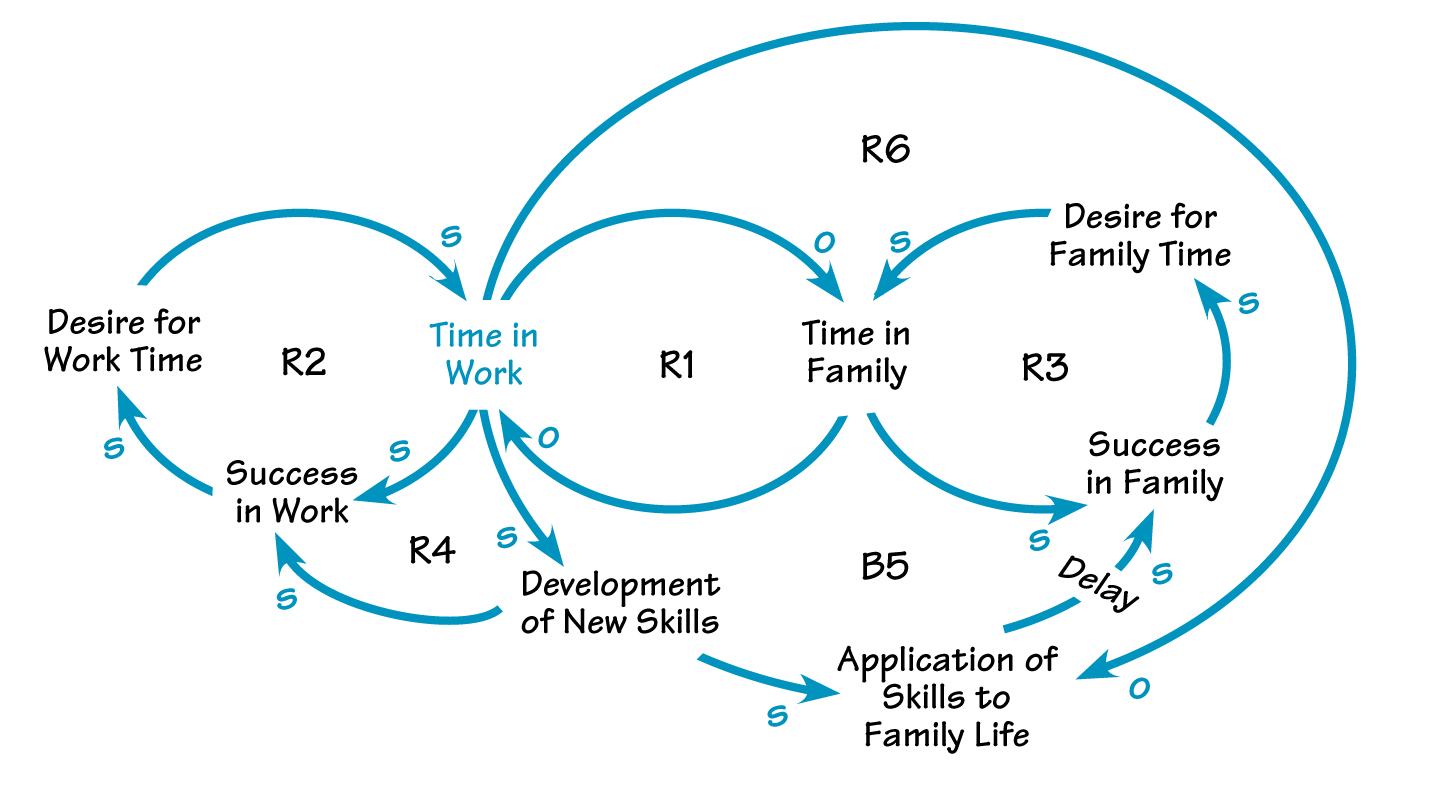

Systems thinking also enables us to appreciate some of the challenges in bringing the five disciplines home. For instance, applying the disciplines to family life often means breaking out of a powerful “Success to the Successful” archetypal structure (see “Bringing the Five Disciplines Home”).

Because many of us spend more time at work than with our families, we tend to become more successful in our professional lives than at home (R1, R2, R3). However, using some of our time at work to develop new interpersonal skills can not only lead to more success at work (R4), but can also provide us with tools to support our success at home (B5). It is helpful to realize that, until we experience more success in the family, we might be tempted to convince ourselves that we are too busy at work to apply the skills back home (R6).

First Steps

Bringing the five disciplines home involves identifying and changing well-entrenched patterns of behavior, which can be both rewarding and painful. We suggest that you start small, be patient, and let your new successes at home naturally shift your work/family balance over time. You might begin by reviewing what you are grateful for in your own life. Then continue by looking at your relationship with one family member. Consider the areas of conflict with that person as a systemic issue, rather than as a problem with him or her. Engage in a learning conversation to begin to shift the dynamic. Over time, you might work toward creating a shared vision with your family, one that combines success at work and success at home to shape a life where each domain energizes and enriches the other.

Marilyn Paul is an independent organization consultant in Lexington, MA with a PhD in organization behavior from Yale. Peter Stroh is a founding partner of Innovation Associates and a principal in its parent company, Arthur D. Little. Marilyn and Peter are a married couple interested in supporting learning families. We welcome learning more about your own experiences in applying these tools, or any others you find helpful. Please send us your stories by e-mail to mbpaul@erols.com.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Betty Byfield Paul.

For Further Reading

Branden, Nathaniel and Devers. What Love Asks of Us. Bantam Books, 1987.

Fritz, Robert. The Path of Least Resistance. Ballantine Books, 1989.

Hendrix, Harville. Getting the Love You Want. Henry Holt and Company, 1988.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home & Home Becomes Work. Henry Holt and Company, 1997.