After 5,000 years, has the Hindu practice of yoga reached its “tipping point”? That’s the expression used by sociologists—and popularized by Malcolm Gladwell in his hot new book, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (Little, Brown, 2000)—to describe the moment when an idea, product, behavior, or message suddenly experiences explosive growth. Since its adoption by American flower children during the 1960s and 1970s, yoga’s appeal has gradually risen and fallen, depending on larger social trends. Recently, however, this ancient discipline has undergone a makeover, fueling an epidemic spread into mainstream culture.

Some pundits cite Madonna’s well-publicized transformation from buff workout queen to lithe Indian princess—complete with henna tattoos—as the start of yoga’s skyrocketing popularity. These days, the practice is the flavor-of-the-month for high-profile musicians including Sting and ’N Sync. Preppy J. Crew stores now feature a line of yoga clothing. And ad agencies have used yoga to hawk products like Jeep trucks and services like Ameritrade.

Limits to Spiritual Growth?

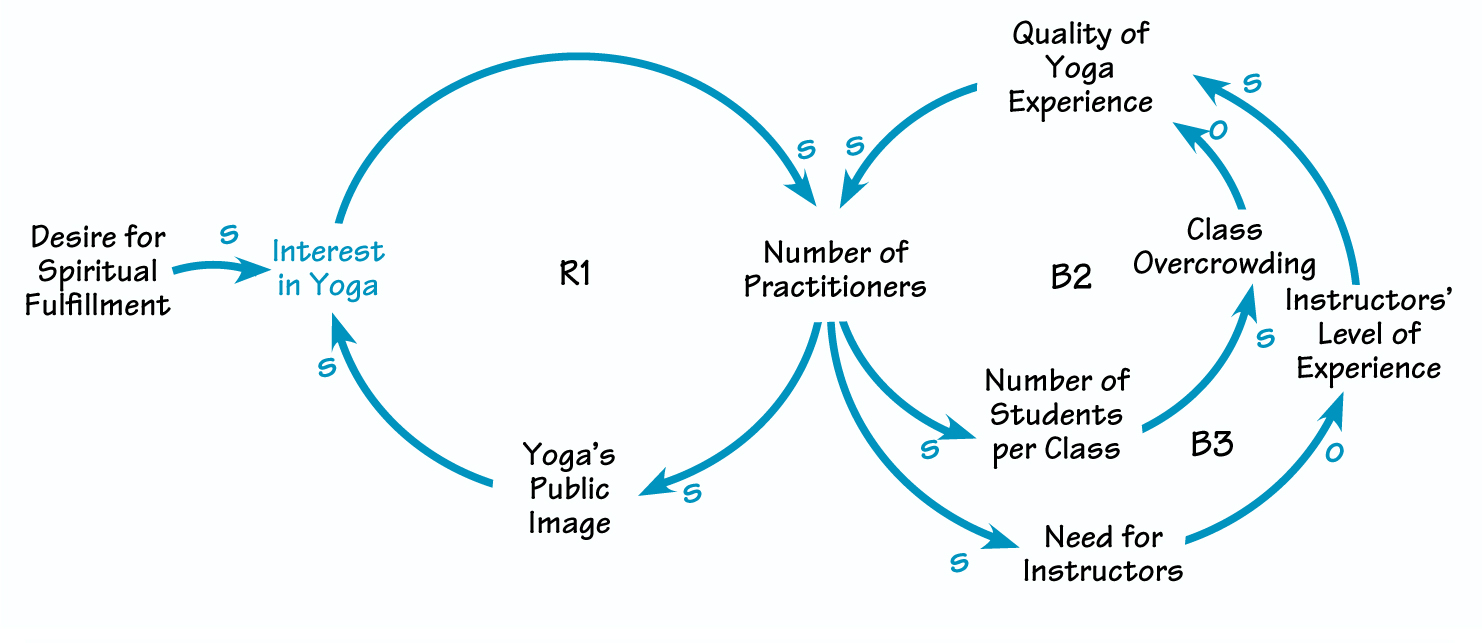

What is driving this trend? As we enter the 21st century, some people have discovered a longing for spiritual fulfillment, in addition to a desire to remain physically fit. For certain individuals, yoga offers opportunities for enlightenment without the emotional baggage that accompanies their childhood religions. Rising interest in the practice has increased the number of practitioners and has boosted yoga’s profile—both in the media and through word of mouth—generating even greater interest (R1 in “Yoga’s Rise—and Fall”).

YOGA’S RISE—AND FALL

People’s longing for spiritual fulfillment has led to rising interest in the practice of yoga (R1). But there are signs that its popularity may well undermine its appeal. As the quality of the experience erodes, the number of practitioners will naturally decline (B2 and B3).

Gladwell documents similar growth trajectories for other social phenomena, such as teen smoking and the renewed desirability of Hush Puppies shoes. But he doesn’t draw much attention to the fact that all epidemics eventually run into limits. In a biological epidemic—for example, the spread of the common cold through a preschool classroom—the disease ultimately runs its course when all susceptible kids have been infected. With a product such as the cellular phone, rapid sales slow once the market has been saturated.

So it is with yoga. Already, there are signs that its popularity may well undermine its appeal. Packed classrooms, less-than-experienced instructors, and conflicts between traditionalists and newbies interfere with practitioners’ ability to cultivate a sense of inner peace. And, in any kind of self-renewal program, as the quality of the experience erodes, the number of practitioners will naturally decline (B2 and B3).

If too many people get turned off—either by the commercialization of a once-sacred practice or by the elbow-to-elbow crowds—then the discipline of yoga may experience a decline in fortune as precipitous as its rise. Longtime devotees may actually relish this inevitability, if it leads to a more authentic form of the discipline.

But the lesson for others is that, if you are lucky or smart enough to “tip” an epidemic, keep in mind that all things must eventually come to an end. Be aware of the limits that await you, and focus on removing or at least postponing those barriers. Otherwise, your success may actually lead to your demise—and 5,000 years is a long time to wait for a second chance.

Janice Molloy is managing editor of THE SYSTEMS THINKER.