This workout seems to be a classic example of the systemic structure “Interdependent Opposites” (see V8N9). The “Interdependent Opposites” structure reflects the view that any value has both an “upside” and a “downside,” and that values that appear to be opposites are typically complementary. While the article highlights the downside of the French approach to wine making and the opportunities left open to “upstart” wine-making countries, we also need to take into account the upside of the French approach in order to see the whole picture.

A wide variety of distinctions have been used to clarify cultural differences, but one that seems pertinent here is the difference between “universalist” and “particularist” values. You may have noticed that some people like to eat the same thing wherever they are—a universal food, such as a Big Mac—while others are interested in trying the specialty of the particular place they are visiting.

While this stems partly from individual differences, culture plays a significant role in shaping what people value. In the U. S., Australia, and New Zealand, people tend to be universalistic, while the French are among the most particularistic in the world. French wine making is thus an expression of the particular qualities of its local community.

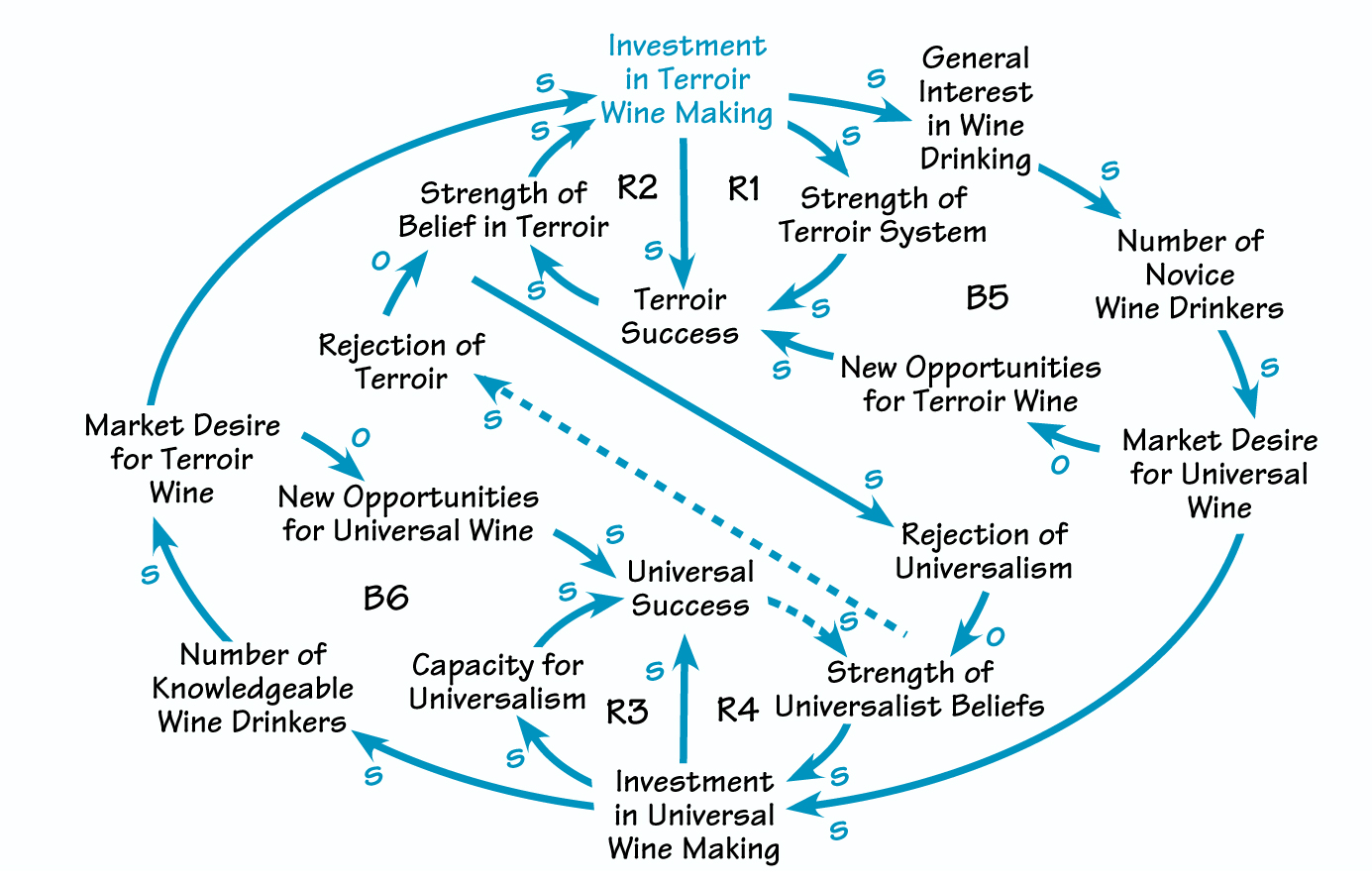

In “Interdependent Opposites in the Wine Industry,” R1 and R2 indicate the reinforcing cycles that have been operating in France for centuries. The French investment in “terroir” wine making has produced success, and has solidified the system that supports this approach. Loop B5 acts to limit the growth of R1 and R2: The terroir approach is relatively expensive, creating opportunities for “universal” wines that are generally affordable and broadly palatable. The market’s growing desire for universal wines creates opportunities that startup wine makers in other countries have grabbed. Increasing investment in universal wine making will bring ongoing success. R3 and R4 show these processes.

There is also a limit to the growth of universal wine (B6). Many consumers, once they have been introduced to wine drinking through universal wines, want to develop their knowledge of wine by moving toward a more terroir-based product. Also, the nature of wine lends itself to a local approach, and wine makers prefer to make terroir wines. For this reason, we believe that the links to “Strength of Universalist Beliefs” and “Rejection of Terroir” are likely to remain weak.

Wine makers in France have often found ways to meet the demands of wine-ignorant but well-heeled customers from other lands. “Particularist” cultures thrive on exceptions, so the French will find a way to take both universal and particular approaches to wine making, though with a clear preference for the particular.

The challenge is for “upstart” countries to do the same, while starting from a universalist preference. If these newer vintners cannot make this transition, our hunch is that they will find themselves in direct competition with universal beverage makers like Coca-Cola, Budweiser, and Starbucks. They will move from being “big-player/low-cost” producers in the wine business, to “small player/relatively high cost” producers in the universal beverage business, something French wine makers have avoided.

Interdependent Opposites in the Wine Industry