At one point in the movie Excalibur, King Arthur lay weakened in bed as his whole kingdom crumbled around him. Most of his knights had already perished in the pursuit of the Holy Grail. But one knight, Perceval, was able to return with the secret of the Holy Grail — that the King and the land were one. The kingdom was decaying because King Arthur’s spirit was dying. It was the bitterness in his own heart that had poisoned the land. The personal choice to let love and forgiveness into his heart was what brought him and the kingdom back.

Merlin had foreshadowed Arthur’s struggle when asked what was the most important thing in the world. “Truth,” he answered. “That’s the most important thing. When a man lies, he murders some part of the world.”

When we live the truth, we are truly alive. But when we live a lie, we kill everything around us. Many people are beginning to acknowledge that the systemic problems and limitations we are currently experiencing — in our organizations, our government, the environment — are the result of our continuing to live a lie rather than face the truth of our connectedness.

We are awakening from a lie that we have been brought up to believe — that the individual is but a cog in the wheel of a great machine called industrial progress — to the realization that ours has been a misguided dream. The myth that human relationships could be broken down into their constituent parts, like the parts of a machine, is being replaced by a growing appreciation for the integrity of the whole and the realization that we are all inter-connected with everything. If life is about a deep commitment to the truth, then the learning journey can be the awakening process.

Commitment to the Truth

How many of us feel that the commitment to truth can comfortably extend to include our work environment? How much honesty can we afford? We have come to fear the truth — and truth-telling — in our organizations, especially when it differs from the “company line.” We assume there must be a good reason for stifling the confrontations that would occur if everyone felt free to voice his or her own truth. We have a sense that chaos will take over — that order in our world will cease.

CREATIVE TENSION

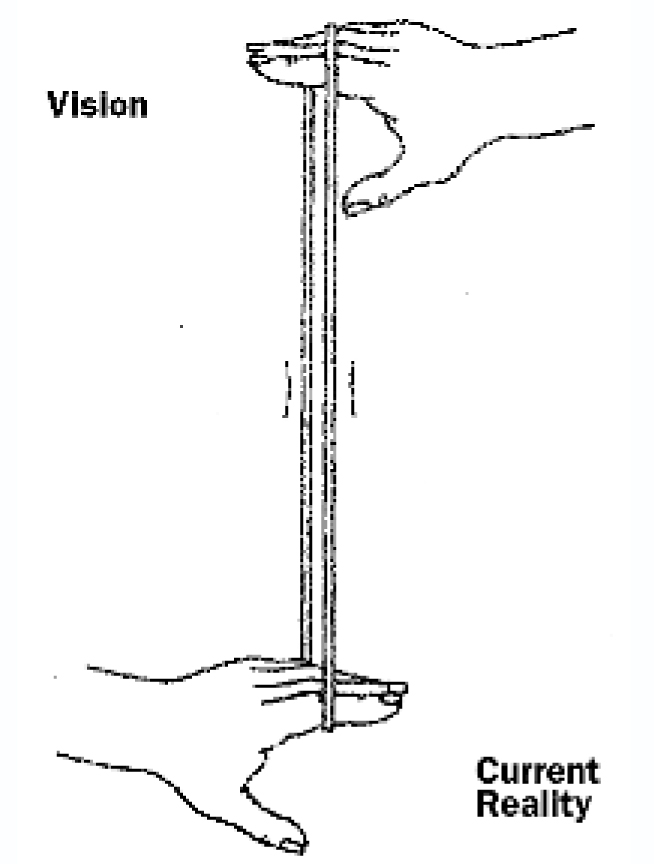

In a learning organization, the discipline of creating shared vision is rooted in personal mastery, and personal mastery is based on a commitment to the truth about current reality. That commitment provides us with a clear idea of where we are and what we believe and allows us to begin to build the creative tension that will propel us toward creating what we truly want (see “Creative Tension” diagram). In order to generate creative tension, we need both a compelling vision, and a clear understanding of our current reality. Without a vision, there is no real motivation to change. Without a clear understanding of where we are, we have no basis for effective action.

Only if we can tell ourselves the truth about the current reality in our organizations can we open ourselves up to new possibilities for innovation and improvement. Only through a commitment to the truth can a learning organization articulate a meaningful set of values that can guide it on its journey (see “Values of a Learning Organization” on p. 3).

When we are unclear about our own truth, we muddy the environment around us. When we clearly express our own truth and also our shared truth — our values — we contribute to the constantly generating field of energy we inhabit. In a “spirited” learning organization, the energy released with this kind of freedom is infectious. People like to come into this kind of space. When we do not have to censor what we really think and care about, we have more energy to devote to creating something that really matters to us.

Multiple “Truths”?

In this constantly changing world, a universe that seems to thrive on diversity and multiplicity and complexity, we can no longer afford to focus our attention on one view or one group of people. Learning organizations need the energy of all of their members, as well as the vision, the aspirations, and inspirations of everyone who is involved in them.

Peter Senge, author of The Fifth Discipline, emphasizes that ongoing conversations about personal visions are vital to creating an organization’s shared vision. As important as building shared vision is, however, Senge notes that the hardest lesson for managers to accept is that “there is nothing you can do to get another person to enroll or commit” to a shared vision. “Enrollment and commitment require freedom of choice.”

In the new documentary about Noam Chomsky called “Manufacturing Consent,” the linguist challenges a young reporter who is condemning him for defending the rights of a professor in France who wrote a book claiming that the holocaust never happened. In reply, Chomsky said, “Free speech is not only for people you agree with. Stalin believed in that kind of free speech; Hitler believed in that kind of free speech. No, free speech is for those you don’t agree with.”

True democracy is based on a fundamental belief in the benefits of listening to as many varied, distinct, and disparate voices as can be heard. What holds people together is that belief in the freedom to speak, to disagree, to have a different view. When that freedom is absent, fragmentation, isolation, and hostility are the result.

“I wonder why we limit ourselves so quickly to one idea or one structure or one perception, or to the idea that ‘truth’ exists in objective form,” questions Margaret Wheatley in her book Leadership and the New Science. “Why would we stay locked in our belief that there is one right way to do something, or one correct interpretation to a situation, when the universe welcomes diversity and seems to thrive on a multiplicity of meanings? Why would we avoid participation and worry only about its risks, when we need more and more eyes to evoke reality?”

Studies of chaos have pointed to how sensitive the universe is, and how important each individual piece is to the shape of the whole. This suggests that we need to encourage differences, rather than smooth them over. Wheatley states, “self-organizing systems demonstrate new relationships between autonomy and control, showing how a large system is able to maintain its overall form and identity only because it tolerates great degrees of individual freedom.”

When we are unclear about our own truth, we muddy the environment around us. When we clearly express our own truth and also our shared truth — our values — we contribute to the constantly generating field of energy we inhabit. In a “spirited” learning organization, the energy released with this kind of freedom is infectious.

The Substance of Spirit

Leadership and the New Science offers some interesting insights into the role of space in an organization. The book explores the more recent teachings of “the new science” — those discoveries in biology, chemistry and physics that challenge us to reshape our world view. In particular, Margaret Wheatley’s study of quantum physics, self-organizing systems, and chaos theory makes some challenging connections between our physical world and the organizations we create.

From quantum physics, we have discovered that we and our world are mostly space (99.999% of an atom is empty space). Wheatley suggests that this vast and invisible thing we call space is actually a field, teeming with information and resources, that we participate in whether we are aware of it or not.

“If we have not bothered to create a field of vision that is coherent and sincere, people will encounter other fields, the ones we have created unintentionally or casually,” she explains. “As employees bump up against contradicting fields, their behavior mirrors those contradictions. We end up with what is common to many organizations, a jumble of behaviors and people going off in different directions, with no clear or identifiable pattern. What we lose when we fail to create consistent messages, when we fail to ‘walk our talk,’ is not just personal integrity. We lose the partnership of a field-rich space that can help bring form and order to the organization.”

If space is not empty, but full of images and messages that we continually feed via our thoughts, words, and actions, then the content of our inner lives — our values, thoughts and beliefs — has a powerful impact on the field of space, or spirit, within our organizations. The quality of that field characterizes the spirit of an organization. We create the field around us, whether it be one which inhibits individuals or encourages them to expand and participate. The field view of organizations suggests the importance of actively working to help shape the spirit of the learning organization.

Leadership

What is the role of the leader in creating this kind of space? The leader of an organization cannot be solely responsible for articulating the vision or spirit of an organization and disseminating it, because that spirit must come from the involvement of all individuals in the organization.

But leaders in learning organizations can help to foster these new ideas by “walking the talk,” demonstrating by their own example that this is not a new flight of fancy, or the management solution-of-the-month. Leaders cannot force a tolerance of diversity; however, they can practice and encourage the exchange of views, especially ones that differ from their own.

We can let go of control as the predominant leadership style and choose to move in sync with the natural universe, which allows for more autonomy among its individual members. More importantly, we can choose to become conscious of our beliefs and attitudes (see “Paradigm-Creating Loops” in Vol. 4, No. 2) and become more willing to see the effect they have on others in our organizations.

Communication, explains Wheatley, is key to this task. “In the past, we may have thought of ourselves as skilled crafters of organizations, assembling the pieces of an organization, exerting our energy on the painstaking creation of links between all those parts. Now we need to imagine ourselves as broadcasters, tall radio beacons of information, pulsing out messages everywhere…Field creation is not just a task for senior managers. Every employee has energy to contribute; in a field-filled space, there are no unimportant players.”

Systems thinking is a discipline that continually prods us to examine how our own actions create our reality and identify ways in which we can change our own behavior to make a difference. With the help of new science discoveries and Margaret Wheatley’s thoughts on their application to the way we view organizations, we have a new arena to explore — the unseen, frontier of field-rich space.

Through exploring the values, truths, and meaning we find in the world, we can contribute to the generative spirit of a learning organization by bringing those intangibles to bear in our everyday lives, consciously and intentionally.

Our unique contribution toward building learning organizations may lie in our ability to know intimately the space we inhabit and how we contribute to the overall spirit of the enterprise. Perhaps that is the secret of the Holy Grail — to know the truth about ourselves, in whatever field we inhabit.

Further reading: Margaret Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science (San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler, 1992). Margaret Wheatley was a keynote speaker at the 1993 Systems Thinking in Action Conference, November 8-10, sponsored by Pegasus Communications.

Daniel H. Kim is the publisher of The Systems Thinker™ and Director of the Learning Lab Research Project at the MIT Organizational Learning Center. Eileen Mullen is a freelance writer living in Somerville, MA.

VALUES OF A LEARNING ORGANIZATION

As a learning organization…

- We believe that each person deserves equal respect as a human being regardless of his or her role or job position.

- We believe that each person should receive equal consideration in helping to develop to his or her full potential.

- We believe that people’s potential should be limited only by the extent of their aspirations, not the artificial barriers of organizational structures or other people’s mental images.

- We recognize that each person’s view is valid and honor the life’s experiences that shaped it.

- We operate on the basis of openness and trust, to nurture an environment where truths can “unfold” and be heard.

- We believe that no human being is more important than another, but each is important in a unique way.

- We value people for who they are and not just for what (or who) they know.