Meeting the challenges that face our society today will require us to go beyond traditional organizational, gender, and ethnic boundaries. Learning in community offers one way to connect the fragmented thinking and acting that perpetuates continued sub-optimization at the expense of the whole community.

Learning communities can be formed within or between “learning organizations” by redrawing boundaries to include the diversity of thought represented within each stakeholder group. The inclusion of diverse perspectives serves the whole community by broadening perspectives to frame the issue and help to evaluate the effectiveness of actions. The sense of wholeness inherent in a learning community is captured in the African expression “it takes a whole village to educate a child.”

A “community,” in this sense, is a group of individuals who freely choose to be and do something together in an ongoing way (as opposed to typical teams within organizations, where the choice to participate can fade behind the everyday routine of going to the office and receiving a paycheck). A member of a learning community is rarely paid to show up; they are there out of their curiosity and commitment to create something that they care about. Learning community members are connected by matters of the heart as well as the mind.

Developing a learning community requires mastery of a collaborative learning process. A stunning example of a community that has both embraced and mastered collaboration is the Association of Mondragon Cooperatives in Spain. The Mondragon Cooperative was founded in 1956 with funds raised from local townspeople to open a small paraffin stove factory with 24 people. Today, they have over 160 cooperative enterprises, employing more than 23,000 members. Their actions are based on a single guiding principle: “How can we do this in a way that serves equally both those in the enterprise and those in the community, rather than serving one at the expense of the other?”

Collaborative Learning

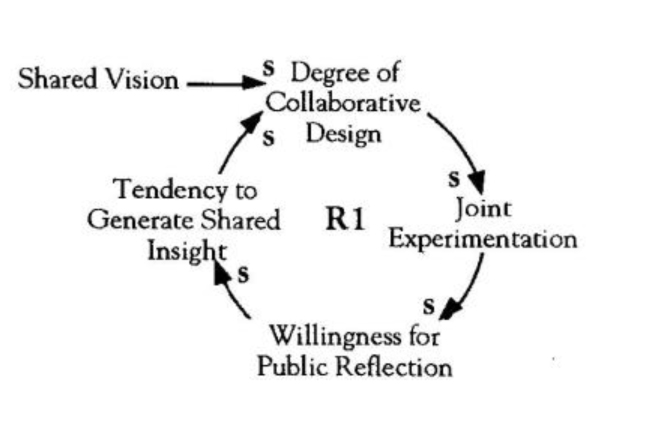

For collaborative learning to occur, there must be shared design about what to explore. Experimenting together with a willingness to reflect collectively can lead to new shared insights, and therefore enhance future design.

For such collaboration to occur, a habit of thinking, acting, and communicating openly must emerge within the community. Creating a structure that can support this interaction is the first step to sustaining learning within the community. The “Collaborative Learning” diagram shows a reinforcing structure that can promote such learning, through joint experimentation that leads to reflection, shared insight, and improved collaborative design of future experimentation.

Collaborative Design. Individual learning takes place, in part, through curiosity followed by experimentation. For collaborative learning to occur, shared curiosity needs to be present, which is translated into the choice of what to collectively explore. Members of the community need to make thoughtful and heart-felt choices about the journey of shared exploration they will embark on together.

Once the path has been chosen, designers who represent the whole system are selected. These designers — a diverse body of stakeholders with the potential for seeing things differently — cross many boundaries. The diversity inherent in these groups is essential to the design of a robust experiment.

Joint Experimentation. The designers are also the actors. Therefore, when collaborative design leads to joint experimentation, the experimenters know what they are looking for in terms of results and are genuinely curious about the outcome. Too often a set of people design an experiment and then ask some other set of people to go off and do it. This typically results in later questioning why the “implementation” failed and why the actors had no ownership in completing the “task.”

Limits to learning

Public Reflection. This continuity of design and experimentation creates the possibility for a common experience that can be publicly discussed afterward. The possibility of open reflection is only realized if the ability and willingness to share and suspend one’s thoughts are also present. In my own work, I have found that the impact increases significantly when clients co-design interventions. After a meeting or offsite we speak candidly about what did and didn’t work, without placing blame on the “consultant” for not knowing better or the “client” for being too closed-minded to appreciate an outside perspective. Out of our shared ownership, we create shared insight.

Shared Insight. If people can openly share their experiences, assumptions, and beliefs with one another about what they thought would happen (what the design was intended to produce) and what actually happened (the results of the joint experimentation), the discrepancy between the two can be perceived and hopefully understood. This process can yield shared insight into the nature of the issue and, if recorded in some form of group memory, can inform future collaborative designs.

Capturing a systemic “picture” of collaborative learning in a causal loop diagram illustrates the importance of the process of interaction rather than an individual player or an elusive end-state. Areas of highest leverage, where a small intervention can significantly affect the health of the system, can then be made more visible, understood and implementable. The beauty of the circle is three-fold: you can start anywhere, it is never over, and there is no focus on individual blame (since everyone is responsible).

Causal loops can also help a learning community develop their ongoing commitment to the collaborative journey of thinking, communicating and acting. The Mondragon Cooperative has drawn the circle defining “we” as the owner-employees, consumers, bank depositors, and the community. Hence it has not limited its activities to business and banking; rather it has participated in nearly every realm of community development, building over 40 cooperative housing complexes, creating private day care, grade school, high school and higher education facilities.

Limits to Learning

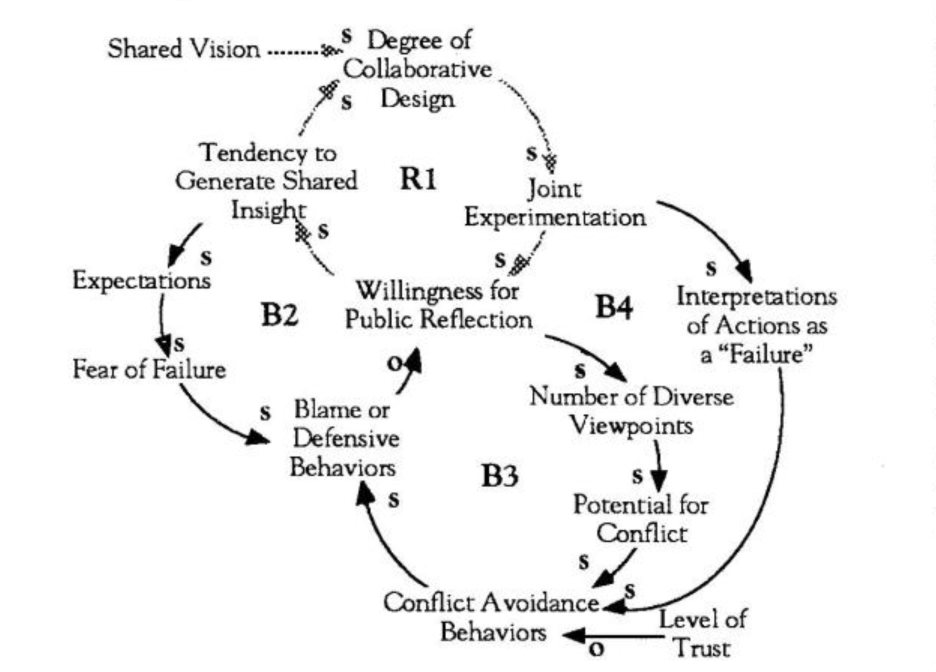

A systems thinker knows nothing grows forever. Consequently the question arises, “What are the limits to learning as a community?” These brakes to learning come in several forms: fear of failure, denial or perception of failure, or the inability to deal with diverse viewpoints gracefully. What all of these limits have in common is the net effect of increasing defensive behaviors in the community (fight or flight) at the expense of open reflection.

As we begin to learn together, our expectations of success start to grow (loop B2 in “Limits to Learning”). If expectations are growing, however, it becomes harder and harder for us to meet them. Fear of failure tends to emerge quickly. Although the group is successfully leaping impasses in its collective understanding, each new gap can seem farther apart than the last one, and uncertainty begins to grow.

When insecurity starts to increase, the need to be defended also grows. People enact defensive behaviors to avoid threat, embarrassment, conflict and anything associated with being “wrong.” Since “the best defense is a strong offense,” people may even begin finger-pointing or blaming others as a means of escaping personal blame.

Defensive routines often appear in the form of denial, which quickly escalates from the personal to the collective (from illusion to delusion to collusion). At some level, I start telling myself, “Everything’s fine, I hope.” I begin to buy into this illusion and the need to believe everything is okay. If a community member and I collectively say that everything is okay (because we do not want to acknowledge any problems), we begin to delude ourselves about what is true. Consciously or unconsciously, we have collectively agreed not to question it. We collude not to inquire into the nature of our actions, and our performance becomes undiscussable. Unfortunately, our ability to reflect or collectively generate insights about the systems of which we are a part also deteriorates.

Yet another potential limit sprouts from the fertile ground of diverse stakeholders participating in the design phase. The greater the diversity of viewpoints, the higher the likelihood that people will interpret the different views as conflicting and shy away from exploring views and suspending assumptions. If conflict avoidance arises, open and honest reflection is undermined and the possibility of creating shared insight or learning dissipates (B3).

Another limit to learning results when an experiment is interpreted as a failure rather than another opportunity for learning. Once again, the need to avoid blame or justify money spent causes defensiveness to dominate over reflectiveness. Soon the collective learning breaks down as people begin to “posture” (sometimes politically) to look good. Information is no longer freely shared; in fact the willingness to look at the data is often undermined in the form of denial (B4).

The nature of the reinforcing loop (RI) is first virtuous, reflective and collective — “we’re in this together.” The balancing loops, however, represent distinctly protective, individualistic behavior which is more about looking good, even at the expense of others (sub-optimization). The virtuous circle becomes a vicious cycle. This is the land of the “hero,” “lone ranger,” or “rugged individualist” who can be counted on to pull it through in the end without needing help from anyone. Yet today’s world of rapid change and complexity is making it harder and harder for any one hero to save the day, and the need for collaboration is painfully apparent.

What all these limits to learning in community have in common is the deterioration of relationships, whether it is a relationship with oneself or others. The “capacity constraint” in learning communities is the capacity for truth in relationship to oneself or others. This inability manifests itself as a barrier to honest communication.

Emptiness

In M. Scott Peck’s book The Different Drum, his model of “community making” includes a stage that is not found in traditional team development models. He characterizes it as “emptiness.” At the individual level, emptiness is about letting go of whatever is getting in the way of one’s relationship to oneself or others. It may involve suspending assumptions, attributions, judgment or expectations. In order for this to occur, however, we must first realize we have these assumptions (or mental models). Appreciating and understanding emptiness is crucial for managers who want to facilitate collaborative learning in their organizations (see “Stages of Community-Making”).

A common dilemma managers face is “How can I facilitate collaborative learning if I can’t do it myself — if I’m not even sure it’s possible?” The temptation is to supply a ready-made solution. However, the real leverage lies in simply acknowledging that the dilemma is part of the journey; one of many that will be encountered along the path. To the extent this dilemma can be voiced, rather than hidden, it will enhance the community’s learning. The moment it is denied, groups retreat into chaos or pseudo-community.

Leadership in Learning Communities

Leadership in learning communities is shared; it moves freely as needed among the group members. This shared sense of responsibility is different from traditional teams, in which the leader is often held accountable by others if something isn’t working as intended. In a learning community, however, each person feels equal responsibility for the “success” of the community’s learning and is willing to look inwardly at what he or she is consciously or unconsciously doing to support or hinder the community’s learning. The commitment to open and honest reflection is internally funded and renewed by the choice to be an ongoing member of the learning community.

I prefer to position the leaders” of learning communities as facilitators or guides. Guides may make occasional comments on the journey, pointing out what is happening along the way, but they cannot lead a group into community—the group must choose for itself. What a guide can do is facilitate the emptying process by continually emptying him or herself and requesting the same of the group. Emptying in this case includes letting go of “old baggage” which may need to be discarded if it prevents members from truly listening or speaking with each other. For example, the most powerful thoughts and feelings I often need to empty are those of having to “fix” myself or others to make everything okay. Learning communities are thus born out of total acceptance of self and others — born out of trust.

Learning Communities

On the other side of emptiness is community, and the only way over is “into and through.” Emptiness is a time when the skills of dialogue are most needed (see “Dialogue: The Power of Collective Thinking,” Vol. 4, No. 3, April 1993). The ability to dialogue can offer a bridge to the other side. I believe open communication begins with being willing and able to see, hear and feel myself. Silence is an invaluable intervention in this stage; quiet is needed to hear the soul speaking through us. When groups learn to dialogue together, meaning moves through the individuals — learning occurs because individuals have emptied themselves and created room for perceiving and acting anew.

Peck’s definition of community goes a long way to define what learning communities could mean: “A group of individuals who have learned to communicate honestly with each other, whose relationships go deeper than their masks of composure,” and who have developed some significant commitment to “rejoice together, mourn together,” and to “delight in each other, make others’ conditions our own.” To become masterful at these kinds of relationships is to build capacity for learning collaboratively, relieving the constraints of different limits to learning.

Peck goes further to state “there can be no vulnerability without risk; there can be no community without vulnerability; there can be no peace — and ultimately no life — without community.” Nor can there be learning without vulnerability. If communities are a safe container for risk and vulnerability, then perhaps they will also be fertile ground for learning.

In many organizations I witness an oscillation between pseudo-community and chaos, where groups are caught in self-sealing vicious spirals. The undiscussable by its nature is undiscussable, which precludes open communication or relationships. If groups find them-selves in emptiness, typically somebody (often a traditional leader) steps in to “fix” or make it better. Although the move is well-intended, it is counterproductive. Yet this is not apparent unless an appreciation for emptiness is present.

Emptiness is a healthy sign of development. Unfortunately, it is not yet part of a popular model of development and not often recognized by facilitators. Too often the traditional facilitator leads the retreat back to pseudo-community (pretending things are better than they arc), or chaos (fixing people and converting them to a “right” point of view) because it is too difficult to be in a place of “not knowing.”

Developing the capacity to live with emptiness means developing the capacity to be in relationship with oneself and others in learning communities. Cultivating emptiness offers a field to discuss the undiscussable and to make the invisible visible in a more reflective way. The experience of giving voice to what needs to be said, and seeing what has always been there, is the experience of learning in community.

Learning communities are a place of truth-seeking and speaking without fear of reprisal or judgment. They are a place where curiosity reigns over knowing and where experimentation is welcome. Developing the capacity to live with “not knowing” when it naturally arises, to learn to be in relationship with oneself and to be reflective rather than defensive in nature is the leverage for learning, and the leverage for learning in community.

“Mondragon: Archetype of Future Business?” World Business Academy Perspectives, 1992, Vol. 6, No. 2, Berreu-Koehler Publishers.

Stephanie Spear, founder of In Care (Hatchvile, MA), is a facilitator of learning within communities. She regularly collaborates with clients in applying the disciplines of organizational learning. Stephanie welcomes others’ stories and perspectives.