You open your latest credit card bill and what do you find? Most likely another promotional offer for frequent flyers: earn bonus miles by staying at the airline’s hotel “partner,” renting a car from its rental “partner,” or charging purchases on a “partner’s” credit card. Without ever paying for an actual flight, you can earn free tickets for future trips.

Although these promotions are great for consumers, they may spell trouble – for the airlines. All of the promotions are tied up in an escalation dynamic, where each time a new promotion is offered by one airline, others are compelled to match or beat it just to stay competitive. Each round of new promotions begets more promotions. Once a company or industry is caught in this “Escalation” structure, it is hard to stop the dynamics.

“Escalation” begins when one party takes actions that are perceived by another as a threat. The second group responds by taking action that improves its own situation but increases the first group’s insecurity. The first group must then increase its activities in order to improve its competitive position relative to the other. The spiraling result of each group trying to retain control can lead to a war in which neither group feels in control (see “Escalation: The Dynamics of Insecurity,” November 1991).

There are two main issues that underlie this structure. First, the “Escalation” archetype describes the dynamics of insecurity. The actions of all involved parties create insecurity, compelling one party to attempt to regain control by taking action, which only leads to retaliation by the other. Second, “Escalation” is often a zero-sum game. A price war in a fixed market, for example, means that when Company A wins more customers, Company B loses customers. Losing customers makes Company B insecure about its ability to sustain itself, so it is forced to react with a countermeasure.

If your company, like the airlines, is stuck in an escalation dynamic, what can you do? The following seven steps can help identify “Escalation” structures at work and show how to break out of them or avoid them altogether.

1. Identify the Competitive Variable

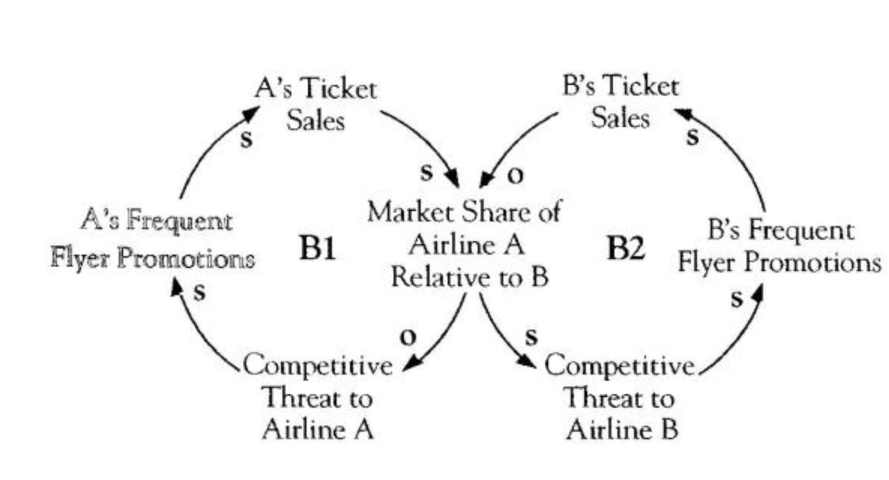

Is your company or industry focused on a single variable as a basis of differentiation from competitors? If you have continually taken action in that area — and your efforts have steadily increased over time — you may already be caught in an escalating dynamic. In the airline industry, for example, the frequent flyer program has gone from being merely a promotional technique to becoming a focal point of competition (see “Escalating Frequent Flyer Promotions”). As the market share of one airline drops relative to another, the increasing competitive threat leads it to use frequent flyer promotions to increase loyalty, and hence, ticket sales (B1). But as the first airline’s market share grows, airline B (and C and D….) must respond with its own promotion to regain market share (B2). All the airlines then become caught in the “Escalation” trap.

2. Name the Key Players

After having identified the competitive focus, then pinpoint the parties whose actions are perceived as the major sources of threat. Ask yourself: “Who are the dominant players that are caught in the cycle?” The critical players in the airline industry, for example, might be seen as the big three carriers, American, Delta, and United. On the other hand, if you think you may be caught in an “Escalation” structure within your company, are there specific groups within departments — rather than whole departments — that are the key participants?

Escalating Frequent Flyer Promotions

3. Map What is Being Threatened

The “Escalation” archetype can be very useful for surfacing a company’s deep-rooted assumptions and core beliefs. If, for example, you feel your market share is being challenged, what does that mean for your organization at a deeper level? Does it threaten your reputation as the market leader or your “no-layoff” track record? You should then examine whether the actions being taken are addressing the actual threat or simply preserving core values that may not be relevant in the new competitive arena.

4. Re-evaluate Relative Measure

Part of the “Escalation” archetype trap is that everyone becomes focused on a single competitive variable. Determining the relative measure that pits each party against the other is crucial for breaking the cycle. Can the foundation of the game be shifted so the players are not really in the same game?

When choosing between airlines, travelers tend to focus on price and schedules rather than service. Promotions have therefore become a primary means for differentiation. The problem with promotions, however, is that they are easily copied and offer no long-term advantage. But if one airline clearly and consistently provided better service and made traveling significantly more enjoyable, people might choose that company because of its great service. SAS Airlines, for example, achieved that with the creation of “Euro Class” — part of its focused strategy to best serve the business traveler.

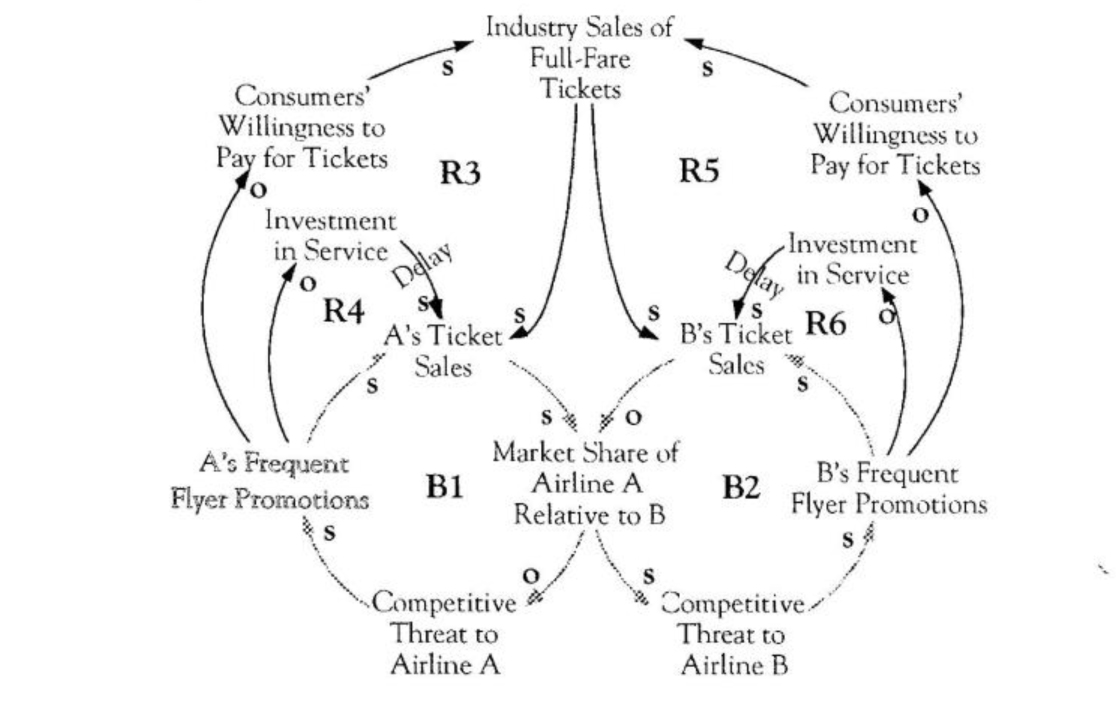

5. Quantify Significant Delays

Delays can distort the true nature of a threat by providing short-term relief while a company or industry’s long-run capability is systematically being undermined. The heavy discounting in the airline industry, for example, will carry long-term implications for the industry’s viability. In the short term, consumers may hail the benefits of price wars and promotions, but these actions can lead to higher fares and worse service in the long run (see “Decline in Airline Service and Full-Fare Sales”). As promotions become more prevalent, consumers’ willingness to pay full fare for tickets decreases, leading CO an industry-wide decrease in sales of full-fare tickets, which decreases each individual airline’s ticket sales (R3 and R5). As the number and variety of an airline’s promotions increases, emphasis on customer service investments may decrease, which can lead to a decline in sales and more promotions activity (R4 and R6). The promotions therefore keep the airlines’ attention away from the areas it needs to invest in, while the delays in the system camouflage the long-term impact.

Decline in Airline Service and Full-Fare Sales

6. Identify a Larger Goal

A leverage point in the “Escalation” archetype is to identify an overall objective that can encompass both part it goals. Once you have identified the larger goals, the next question to ask is whether the system is structured to achieve those goals. Are there ways businesses are participating to ensure that the larger goals will he met? Are there ways to actually expand the market, rather than having to cut up a limited pie? To address these larger issues, some kind of central governing body (not necessarily the government) that can serve the needs of the whole community may be necessary.

For example, as a nation we need to ask, “Why do we need a healthy domestic airline industry in the first place?” If we acknowledge that the viability of the whole industry is important for the nation, then coordinated actions at an industry level must be identified.

7. Learn to Avoid “Escalation” Traps

The best antidote to the “Escalation” archetype is to avoid getting caught in it in the first place. One of the reasons we get caught in escalation dynamics may stem directly from how our thoughts around competition are structured. In a competition model, there is no room for collaboration; yet the “Escalation” archetype suggests that cut-throat competition serves no one well in the long run.

The “Escalation” archetype can serve as a starting point for exploring ways that collaborative competition can occur. Collaborative competition may serve as the means for bringing out the best in each company (or department) by encouraging it to excel in its own unique way, rather than being an also-ran in a crowded field of look-alikes.