In the world of mail-order computers, maintaining a balance between improving technology and developing new markets has always been a challenge. Gateway 2000 is currently facing this issue. According to a recent Business Week article, the company is experiencing increased competition at home while preparing to expand into new overseas and domestic markets. Gateway must now find a strategy that encompasses this expansion — while still keeping its service quality high and its initial customer base happy (“Why Gateway is Racing to Answer on the First Ring,” September 13, 1993).

Gateway took the lead in the $6.5 billion U.S. mail-order PC computer business by combining low production costs with a customer base of small businesses and technically-knowledgeable users. Low taxes and cheap labor at its headquarters in South Dakota allowed Gateway to keep its production costs low relative to competitors. A “no-frills” corporate style also allowed the company to undercut competitors on price. These benefits enabled Gateway to offer its customers a low-cost, high-quality product along with good customer service.

According to the Business Week article, however, “Gateway is at a cross-roads that has tripped up many a PC company in the past. It must keep revenues growing like mad while maintaining quality and service — and not losing control of costs.” For the first time since its founding, Gateway experienced a drop in sales over the past year. Gateway CEO Ted Waitt attributes the decline in sales to a backlog of orders from last December that inflated first quarter results. Future drops in sales, however, may indicate a larger problem — declining customer service quality.

Finding and training technical and assembly-line workers in South Dakota quickly enough to keep up with customer demand has been difficult. This staff shortage has increased customer complaints regarding delayed deliveries and long waits on customer service lines. By adding 75 new phone lines and expanding its cadre of 176 technical support personnel, Gateway has managed to cut the time that customers must wait to speak to a technician in half. Still, some customers may spend up to six minutes on hold.

At the same time it is experiencing these problems at home, Gateway is planning to create a production facility in Ireland and market mail-order PCs in Britain, France, and Germany. These expansion efforts mirror Gateway’s early U.S. strategy of finding a production base that will keep initial costs low, thus allowing the company to provide quality service at a lower cost. Gateway may find, however, that plans to expand overseas are more difficult to implement with a dissatisfied customer base at home.

Another part of the company’s strategy for increasing its competitive position involves marketing to a broader domestic corporate base while expanding its market overseas (see “Gateway’s Growth Strategy”). To increase corporate buyers’ purchases from the current 40 percent of sales, the company has created a new major accounts team that plans to target companies like Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc. and Union Pacific Corporation. However, Dell Computer Corporation is already challenging this strategy with a marketing campaign that is targeted specifically at Gateway. At the same time, larger computer companies like IBM and Compaq are challenging Gateway in its traditional mail-order PC market.

Discussion

- Flow fast should Gateway expand its technical support capacity relative to its revenue growth?

- Once a capacity shortfall has been identified, the acquisition delays are usually fairly obvious. But what are some of the hidden sources of delay?

- Performance standards do not necessarily have to erode to be ineffective; they can become obsolete. How might Gateway’s current standards of service become inadequate?

- Is Gateway’s goal of expanding into new markets, maintaining profit margins, and improving service quality an achievable one?

Gateway's Growth Strategy

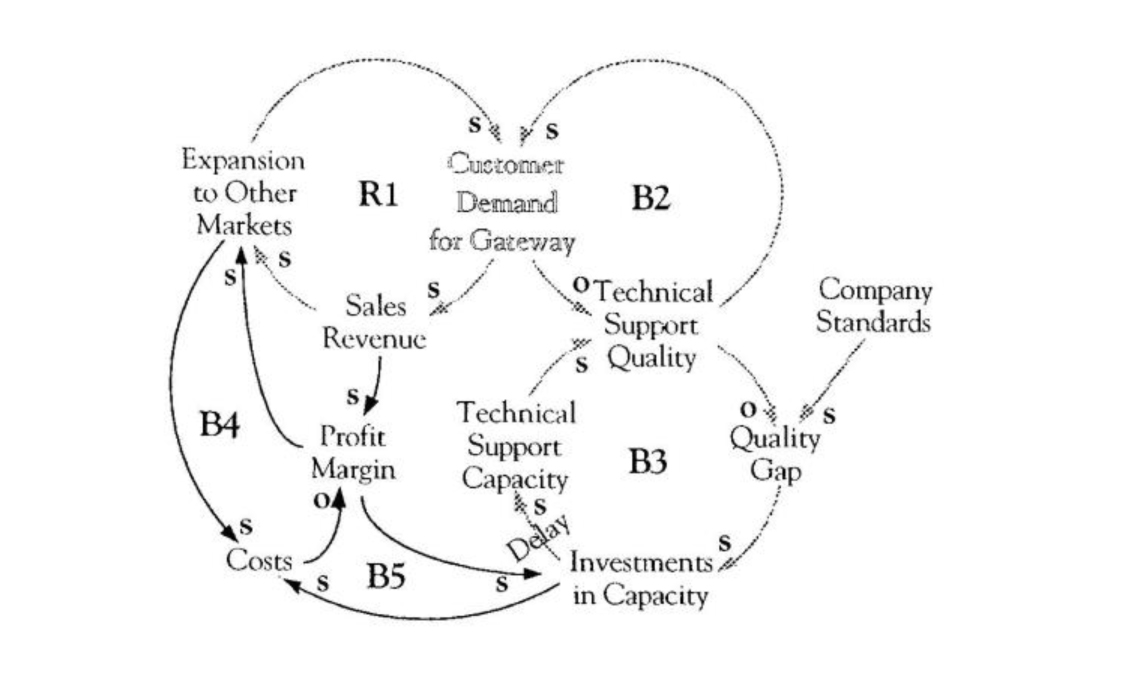

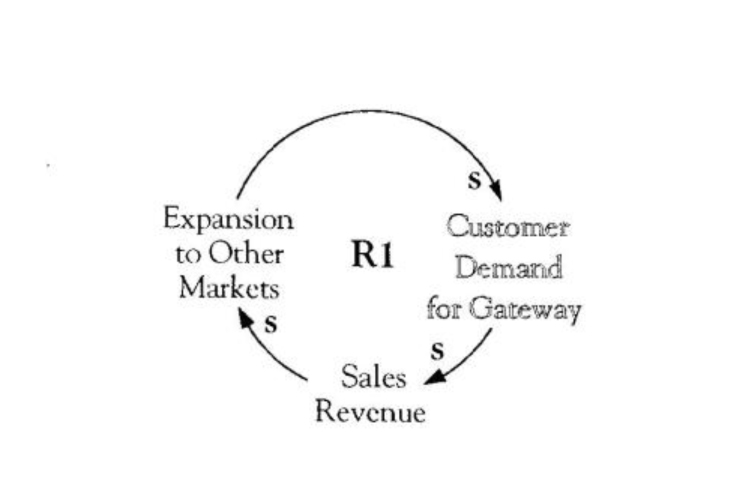

As customer demand for Gateway’s products increases. revenues also increase, providing the necessary capital to expand into new markets and further spur demand (R1).

Gateway may find that it is caught in a pattern characteristic of the “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype, in which rapidly-expanding demand for a product outstrips the ability to add capacity to meet it. Although the solution of adding the needed capacity seems obvious, the dynamics created by this structure can be subtle and the appropriate capacity level can be difficult to assess.

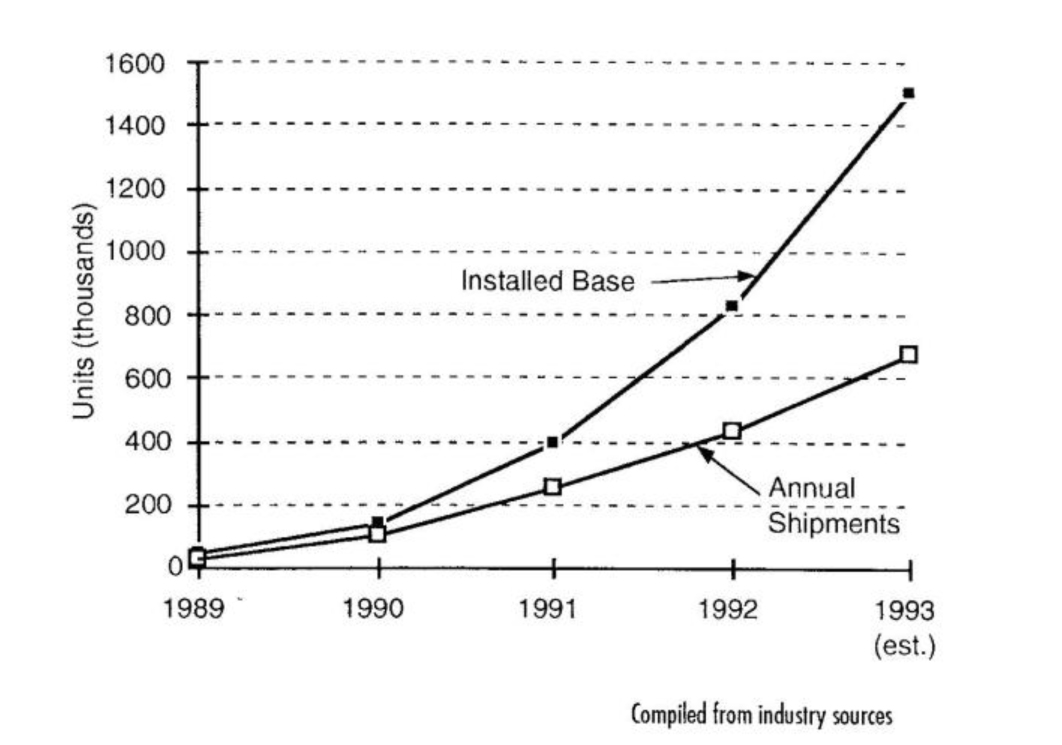

In Gateway’s situation, the current technical support service problems are a direct result of its sales success. Revenues have skyrocketed from a mere $100,000 in 1985 (its first year) to $70 million in 1989 and $1.11 billion in 1992. Estimated revenues for 1993 are around $1.7 billion. As the number of units sold continues to climb, the number of customers requiring service also increases. This suggests that the service capacity should be expanded at least as rapidly as the growth in shipments. In terms of total number of employees, Gateway appears to have kept pace with revenue growth. From 1990 to 1992, its revenues almost quadrupled from $275 million to $1.11 billion, while the employee ranks grew almost five-fold, from 400 to almost 1860.

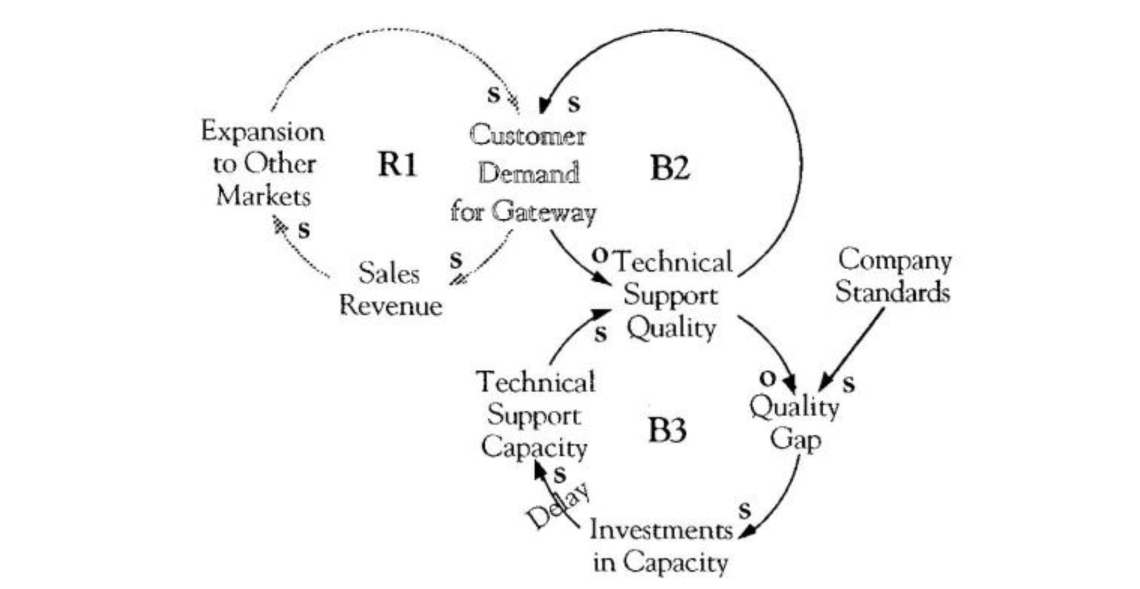

But, as Gateway has learned, simply adding workers is one thing, finding people with the appropriate skills and experience is altogether different. In particular, acquiring and training service technicians has proved to be a more difficult process than the company may have first realized. Consequently, Gateway customers have been experiencing delivery delays and busy customer service phone lines which, over time, will dampen demand (B2 in “Underinvestment in Technical Support”).

Super-Exponential Growth in Installed Base

Hidden Delays

When a company experiences a decline in its service quality, halting the slide requires investing in more capacity as quickly as possible. In making the decision to invest, it is critical to immediately recognize when the performance actually falls off and when the needed capacity should be added. In many cases, the delay between recognizing declining levels of service and adding needed capacity widens due to an inability and/or unwillingness to acknowledge that current efforts to address the declining quality may be inadequate.

Keeping production capacity in step with rapid growth is hard enough. But the challenge of keeping after-sales support on track is compounded by the fact that when sales are growing linearly, the installed base is growing exponentially; and when sales are growing exponentially, the installed base is growing super-exponentially (see “Super-Exponential Growth in Installed Base”). This means that the number of service technicians may need to grow at a rate much faster than the organization as a whole.

If Gateway’s mental model is that the number of service technicians should grow at the same rate as sales, the company is likely to chronically underinvest and will fail to provide customers with the level of support offered in the past. This delay in recognizing the true capacity needs may become a self-limiting factor for continued growth by keeping the technical support quality low (and keeping loop B2 active). If the low service quality persists and depresses customer demand, the lower demand will be easier CO service. This will reduce the quality gap, which will lower investments in capacity and lead to a lower technical support quality (B3). Loops B2 and B3 can spiral in a vicious figure-8 reinforcing loop that leads to lower demand and lower service capacity, all the while maintaining what is believed to be an “acceptable” level of service.

Inadequate Performance Standards

Even it Gateway recognizes the need to expand its technical support at an accelerated rate and is somehow able to hire and train all the people the company feels it needs, it can still fall victim to the figure-8 dynamic. This is likely to happen if Gateway’s performance standards, which drive its investment decisions, are not continually updated to fit the company’s current situation.

The value of a performance standard can effectively “erode” if it remains unchanged while the needs of the market-place continue to change. If the standard is never revised to meet current market conditions, adequate investments needed to support the market’s changing quality expectations will never be achieved. The result: demand will decrease until it hits the number (and type) of customers who are satisfied with the company’s traditional standard.

For example, the service needs and expectations of the new corporate customers that Gateway is targeting will most likely be higher than its original core market of technically-savvy users. And people who are accustomed to IBM-style service may find Gateway’s service level, even at its best, inadequate. A push into such new markets may require a substantial redefinition of Gateway’s notion of high service quality.

Conflicting Goals

Improving customer service in the face of continuing rapid growth is a challenge in and of itself. Couple that with a strategy for entering foreign markets and targeting more established corporate buyers, while still preserving current profit margins, and the goals seem to be at cross purposes — at least in the short term (see “Expansion, Investments, and Profit Margin”).

Expansion into the direct mail market overseas involves a complicated and costly web of marketing and shipping arrangements which will require significant investments. For example, different countries in the European Community will require customized computer systems and marketing plans. At the same time, the new corporate buyers and the ever-expanding installed base at home will require further investment in technical support capacity. Both investments will increase costs and squeeze profit margins, since sales are not likely to rise very fast in the early stages of overseas expansion. If both investments are pursued aggressively, profits will suffer and there will be pressures to cut back (B4 and B5). However, if technical support investments are pursued less aggressively, the new markets can still be targeted and profit margins may be maintained. The risk, of course, is that service quality may suffer.

One possible scenario for Gateway is to proceed with its expansion plans while keeping a careful eye on the bottom line. Additions to technical support can be made on an incremental basis, but only after there are complaints that service quality is inadequate. When customers defect, Gateway can try to beef up service while embarking on more expansion plans to maintain revenues. In the long run, however, these choices could lead to a reputation for poor service, which may eventually necessitate additional price cuts to regain customers. This, in turn, would squeeze margins and create pressure to improve them, perhaps by cutting back on service investments.

A better scenario may be for Gateway to commit to the necessary investments in tech support and overseas expansion plans, but expect lower profit margins in the short term. By relaxing the profit margin goal in the short term, the company may be better able to sustain healthy profit margins once it has built the necessary infrastructure to support its new markets.

Underinvestment in Technical Support

Expansion, Investments, and Profit Margin