If you look at the data from your last physical, you will most likely see standard diagnostic tests such as EKG, Blood Pressure, and Blood Chemistry. Together they provide a snapshot of your overall health.

The most revealing category seems to be Blood Chemistry, which displays your individual specs relative to an acceptable range or value. The line items I hurriedly search for are “Cholesterol” and ‘Triglycerides.” It is amazing what I say to myself when I see those numbers: “I better cut out the fat…I need to invest in more exercise…I really thought I was in better shape.” All of this data and my mental model of what it is telling me can even make me change my whole lifestyle — at least for a little while.

In a business enterprise, the equivalent of the Blood Chemistry test is the earning strength of business over time; a true indicator of business health and future performance potential. The financial investment community calls it EBITDA or Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization. It is also amazing what we say to ourselves when we see those earnings numbers: “I better cut out the fat (reduce costs)…I better invest in more exercise (new assets and technology)…I really thought I was in better shape (what are our shareholders going to think?).” It is our mental models about this information that compel us to take particular actions to enhance an earnings stream or correct an earnings leak.

Enhancing Earnings

For many years, I have participated in gatherings both within and outside of Armco where people have debated different strategies designed to enhance earnings. The most common conversations would result in a list including the following topics:

- How to increase sales volume

- How to increase selling price

- How to lower costs

- How to increase productivity

- What new technology to invest in

- What new assets to invest in

- How to expand profitable business lines

- How to exit unprofitable business lines

These actions are typically recognized as the hard measurable actions that can most dramatically enhance earnings. We went through years of making these lists before we realized we were relying on the same old solutions. Not only were we using the same old tools, but we had always relied on the same thinking to test our beliefs about our business.

All along we assumed that our people were continually learning by experience. We also thought we needed new programs such as Total Quality Management to involve people in the process, to give them more responsibility and accountability. And then individuals would be empowered to enhance earnings.

We didn’t realize how much we were fooling ourselves.

Learning and Earning

At one session, after making the same list once again, we suddenly noticed that we had already seen all of the ideas before. At similar crossroads in the past, we would usually bring in someone from the outside and ask for new ideas, trusting their thinking. But this time, we attempted to illustrate our dilemma by trying to help people to “see” things on the inside, to get to what is behind all of our work behavior.

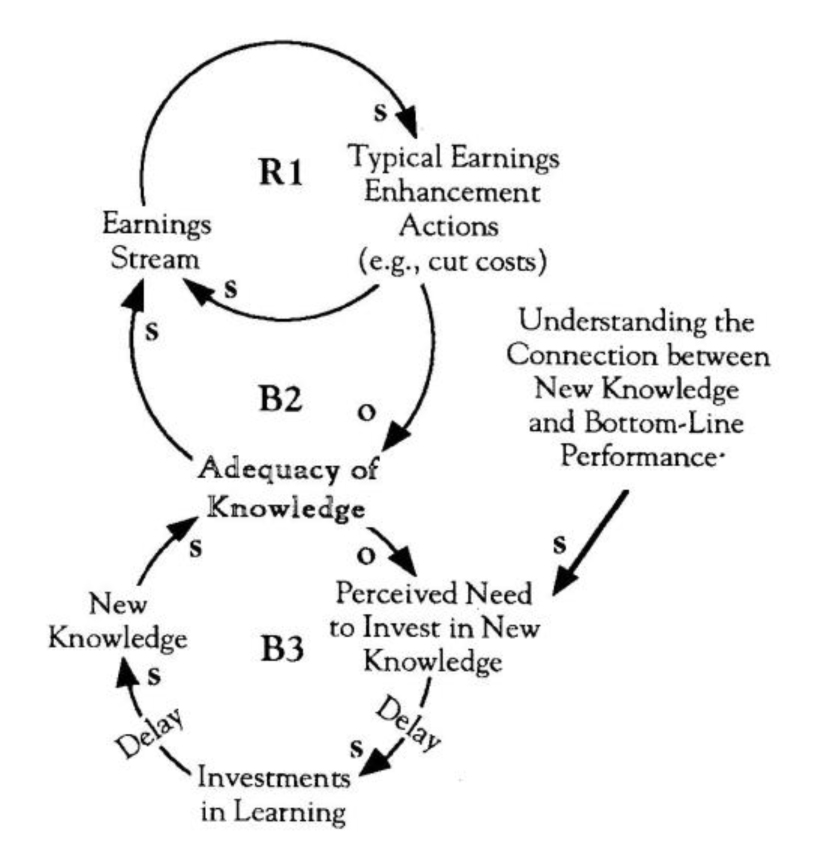

As we attempted to map the dynamics using a causal loop diagram, we discovered that we were caught in a reinforcing loop in which our current knowledge led to the same traditional solutions and ways of enhancing earnings. We were, in effect, coming up with a lot of new ways to use the same old hammer. It was only as we challenged ourselves to analyze these old tools and methods that we discovered a major constraint in our system — our capacity to introduce new knowledge and tools to help people test current behaviors and areas for change.

Capacity to Enhance Earnings Stream

As we explored this constraint, we realized that we were caught in a “Growth and Underinvestment” situation. At the core of “Growth and Underinvestment” is a reinforcing loop that drives the growth of a performance indicator and a balancing force (or forces) which opposes that growth (essentially the two loops that make up a “Limits to Success”). The additional loop in “Growth and Underinvestment” shows how deteriorating performance can justify underinvesting in the very capacity that is needed to lift the limit to growth.

In our case, the adequacy of our current knowledge was balancing our ability to enhance our earnings. At the same time, we justified our underinvestment in new knowledge because we undervalued the connection between knowledge and bottom-line performance (see “Capacity to Enhance Earnings Stream”). Whenever the word learning came up, everyone avoided it because it was perceived as a “soft” issue. We therefore allowed ourselves to defend our lack of knowledge to shield us from what really was limiting us.

Measuring Hard vs. Soft Investments

To further explore this “Growth and Underinvestment” situation, we attempted to challenge our assumptions behind capacity investment decisions. Traditionally, justifying investment in new capacity requires actual accounting data that proves the inadequacy of current strategies and capacity. In this case, however, the capacity issue we were dealing with — knowledge — was hard for us to quantify.

I have yet to hear anyone connect an investment in learning as a direct influence on enhancing earnings. In most cases, if the subject surfaces at all, someone says, “That is soft stuff. We need the hard stuff that we know we can trace to the bottom line.” The operating belief is that addressing soft issues (such as the impact of learning on earnings) would take money and attention away from the real enhancement opportunities — the hard actions.

Once we discovered that we were using the words soft and hard to divert our attention away from robust business thinking, we recognized that our reliance on “hard” data in our investment strategy was distracting us from the most fundamental driver of earnings…new knowledge. We had justified the underinvestment in learning by investing instead in technology and equipment, and by participating in self-talk to defend our denial and further justify the underinvestment in learning. Meanwhile, our earnings growth potential suffered. By investing on the hard side, we were also able to avoid (at least for the time being) the long delay associated with investments in learning and developing new ways of thinking.

As a result of our discussions, we have discovered that it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that “what is measurable is what is important.” Measurability is one reason why most people want diagnostic tests when they go to a physician; it gives them results in data form. Ideally, the tests should help get at the root of most health problems, but they often fall short of this goal and lead to taking only symptomatic solutions.

A business, like the human body, is a complex system whose behavior is often counterintuitive. The solutions that are the most empirical and easier to apply are often the ones that can have the most drastic results. The issues that traditionally have been classified as “soft,” on the other hand, may actually have the highest leverage for producing long lasting change. Therefore, to change our current ways of thinking, we need to recognize that enhancing our organization’s capacity to acquire new knowledge (or learning) is directly linked to our capacity to think, act, and change. These factors have a direct influence on earnings.

So instead of relying on words such as hard and soft to defend our current thinking, we are focusing more on the language of systems thinking to promote a more systemic approach to issues. Our new thinking about these issues has led us to work toward investing more in formulating the tough questions, instead of spending money to find the measurable answers.

Creating Open Spaces for Learning

Investing in learning, therefore, includes not only a financial investment in training and workshops, but also in efforts to create the open space in which we can think about the way we think. This includes research to discover and analyze current work behaviors as well as investments in new ways to surface and unlock the way we think and learn. Generative dialogue, mind-maps, competency modeling, and systems thinking are all effective ways to focus on being behavior-based rather than program-based in our learning.

Before we acknowledged these issues in our company, open space for thinking was something we did not respect. Creating this open space required us as individuals to have the courage to ask the tough questions and to challenge traditional ways of thinking. It also required us to bring defensive routines out into the open while being supportive of each other. Essentially, creating an open space enabled us as a group to turn a potentially negative process into a learning process.

The real long-term value of this kind of thinking is in leading an organization to go beyond empowering its people. Today, the word empowerment is used in the context of giving responsibility. A step beyond empowerment, however, is “inspirement.” Inspiring people means that individuals will come looking for responsibility and ownership. It will be a driving factor in helping us to create healthy businesses — just as individuals can work toward creating a more healthy lifestyle.

B.C. Huselton is the VP of Human Resources and Business Systems at Armco Worldwide Grinding Systems. He is Armco’s liaison officer to the M.1.T. Organizational Learning Center, and will be a presenter at the 1993 Systems Thinking Action Conference.