My wife and I moved to Israel on September 25, 2000—three days before the Al Aqsa Intifada began. Our hopes for a wide-ranging sabbatical, including development work with both Israelis and Palestinians, were quickly dashed. Instead, almost immediately, we were caught up along with everyone else in concerns for our own security as well as in conversations and media reports that inevitably focused on two questions: “Why now?” and “Who is to blame?”

The first question seemed important because it appeared that both sides had been moving toward a peaceful settlement since 1993, when they signed the Oslo Accords. Certain parts of the West Bank had been returned to full Palestinian control on an agreed-upon path to Palestinian statehood, and the newly formed Palestinian Authority had publicly announced its acceptance of Israel’s right to exist. Just two months before we moved to Israel, Prime Minister Ehud Barak had made the strongest Israeli offer yet for completing negotiations and paving the way for a Palestinian state comprising most of the West Bank and Gaza—although, much to the surprise of most Israelis, the offer was rejected.

The second question seems almost inevitable in human relations when things do not go the way people want them to. Instead of considering our responsibility for creating certain situations, we quickly seek to blame others. Moreover, in this case, there were plenty of likely candidates: Yasser Arafat, the Palestinian leader who turned down Barak’s breakthrough offer; Ariel Sharon, the Israeli right-wing leader whose visit to the Al Aqsa mosque complex sparked the Palestinian riots; Barak, for appearing to force the Palestinian leadership into a corner and refusing to meet with Arafat face-to-face at Camp David; and President Clinton, for appearing to side with Israel against the Palestinians during these same negotiations.

As unavoidable as these two questions are, I believe they are the wrong ones. As a systems thinker trained to look for the non-obvious interdependencies producing chronic problems, I found it pointless to ask “Why now?” about a conflict that has been going on for anywhere from 30-50 years at a minimum to nearly 4,000 years at the extreme. Similarly, it made little sense to blame anyone when the conflict has extended well beyond the political if not physical lifetimes of most of the leaders mentioned above and other participants in the current crisis.

Instead, I began to ask a different set of questions:

- Why does this problem persist despite people’s extensive efforts to solve it?

- Why do Israelis invest so much to increase their sense of security, yet feel so insecure?

- Why do Palestinians, despite enduring the loss of lives and extreme economic hardship, gain so little of the respect and sovereignty they try so hard to achieve?

- Why is it difficult for those people on both sides who want a workable compromise to gain sufficient support for solutions they perceive as possible?

- Where is the leverage in the conflict, that is, what can people do to produce a sustainable systemwide solution?

The field of systems thinking is especially effective for enabling people to understand why they have been unsuccessful in solving chronic problems despite their best efforts. While a systems view can’t fully answer these questions, it can illuminate how people think—and the consequences of their thoughts and actions on the results they achieve—in ways that can help them see and achieve sustainable new solutions. By understanding the exact nature of the vicious circles we have been trapped in, we can create new patterns of relationships that serve us better. I set about to apply systems thinking to the Middle East crisis to see if I could shed light on possible ways out of the ongoing tragedy.

A Four-Stage Cycle

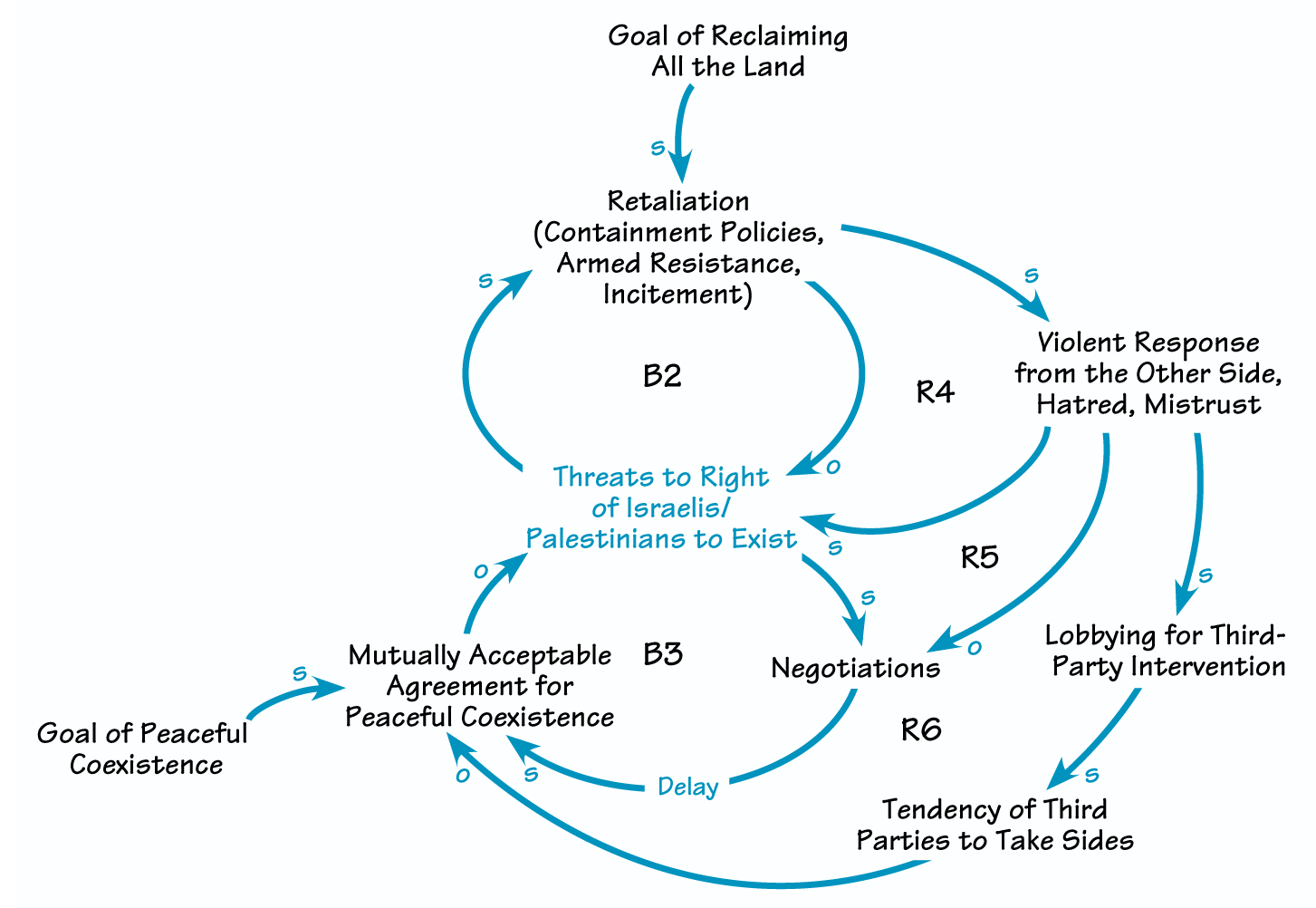

My view is that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict proceeds through a pattern of four stages: 1. Both sides fight for the right to exist. 2. The tension escalates. 3. Pressure leads to negotiations. 4. Peace efforts break down.

When peace efforts break down, the two sides cycle back to the first stage and intensify their fight for the right to exist (see “A Cycle of Violence”). From a systemic perspective, this pattern of behavior indicates that the “solutions” that the two parties are employing are unintentionally making the problem worse, or at least perpetuating it.

1. Both Sides Fight for the Right to Exist. What makes the Israeli-Palestinian conflict so intractable is that both sides see themselves battling to establish their basic right to exist. Israelis and Palestinians have become ardent enemies because each claims the same land. While some voices on each side acknowledge the right of the other to exist and are willing to exchange land for peace, others— often the more dominant voices— deny this right and refuse to negotiate. As a result, many ask, “How can coexistence be an option when the other side challenges our right to exist?”

Israel’s fears about its existence are justified by past events. The country came into being in 1948, shortly after one-third of the world’s Jews were exterminated in World War II. Immediately after it was founded, Israel was threatened by five surrounding Arab states, which vowed to “drive the Jews into the sea.” The Arabs felt that the partition proposed by the British and agreed on by the U. N. took land away from Arabs who had lived there for generations. Border raids by Egypt and Syria led to additional wars in 1956, 1967, and 1973. To protect its northern border, Israel occupied southern Lebanon from 1982 to 2000.

Israelis interpret many Palestinian actions as proof that the Palestinians do not recognize their right to exist. For example, the current Intifada, the Palestinians’ demand for the full right of return of its refugees to their homeland in what is now Israel, and continued anti-Semitic incidents abroad remind them of their vulnerability and the need for a Jewish state.

Meanwhile, the Palestinian people have never controlled their own destiny. The Ottoman Empire controlled their land for 400 years. The British took over in 1917 and ruled Palestine until 1948. In the Israeli War of Independence, an estimated 600,000 Palestinian refugees fled parts of Palestine that were later absorbed by Israel. Their numbers, including descendants, have now swelled into the millions. Jordan took over rule of the Palestinian West Bank from the British and held it until 1967, when Israel won that territory during the Six-Day War. Since then, Israel has established, expanded, and consistently defended settlements in the West Bank—often land lived on for centuries by Palestinians. Palestinians have frequently received a hostile reception through-out the Arab world. Since 1970, their attempts to resettle first in Jordan and then in Egypt and Syria were largely denied. Palestinians who have established themselves in Lebanon cannot practice professions. The only country that currently recognizes Palestinians as citizens is Jordan. Many suffer in refugee camps throughout the region, hoping to return to the lands they were forced to flee.

In their efforts to assert their right to exist, most Palestinians and Israelis will only consider two options: One is to negotiate an agreement of peaceful coexistence that divides the land of Palestine into two viable states; the other is to try to maintain or wrest control of all of the land at the expense of the other party. For a long time, many on both sides seemed to favor the first alternative, despite the powerful influence of extremists acting to achieve the second. But the profound mistrust the Israelis and Palestinians have developed for each other has caused more people on both sides to be drawn to the second alternative, despite the costs involved.

Two powerful factors entice both sides to fight for control of all the land: threat and desire. For most Israelis, the primary threat is to their security. Since 1967, the country’s policies have also been fueled by the desire of a powerful minority of religious Jews to retain control over the historical Jewish lands of Judea and Samaria, which constitute much of the West Bank. Israel’s response to threats to its security, as well as to pressures from the religious right, has been to control Palestinian movements through-out the territory through blockades, check points, and permits—actions that might be consider edmilitarily defensible but that are often implemented in ways that feel humiliating to the Palestinians. Israel has conducted targeted assassinations, bombed strategic Palestinian infrastructure, appropriated additional land to protect the settlers, defended the violent acts of some settlers, and killed civilians when under attack.

For Palestinians, the threat to their existence involves not just the lack of a homeland but the lack of respect they perceive from others. They feel ignored for the losses they have incurred and demeaned by both the actions and broken promises of the Israelis. Their anger at their history of mistreatment by foreign rulers, fanned by an Israeli occupation of the West Bank that the U. N. considers illegal (U. N. Resolution 242 defines the West Bank as “occupied territory”), leads them to demand respect as well as sovereignty. Furthermore, although Palestinian moderates would accept a viable state that has contiguous borders within the West Bank, comprises almost all of the West Bank and Gaza, and includes East Jerusalem as its capital, many Palestinians dream of reclaiming all of the land of their forebears—a reclamation that would result in the elimination of Israel.

Because their military position is weak relative to Israel’s, Palestinians fight through sniper attacks, verbal incitement, and suicide bombings against civilians. They justify their reliance on violence by observing that, in the past, Israel has not kept its promises unless it was physically provoked. For example, many view Israel’s decision to remove all of its soldiers from southern Lebanon in the spring of 2000 as a response to the violent resistance of Hezbollah fighters. Palestinian leaders also maintain strict controls over the information available to their own people—for example, by denying Israel’s existence in student textbooks and maps—and incite refugees to believe that they will one day reclaim all of their land.

A CYCLE OF VIOLENCE

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict proceeds through a pattern of four stages: Both sides fight for the right to exist; the tension escalates; pressure leads to negotiations; and peace efforts break down (R1). When peace efforts break down, the two sides cycle back to the first stage. This pattern of behavior indicates that the “solutions” that the two parties are employing are unintentionally making the problem worse, or at least perpetuating it.

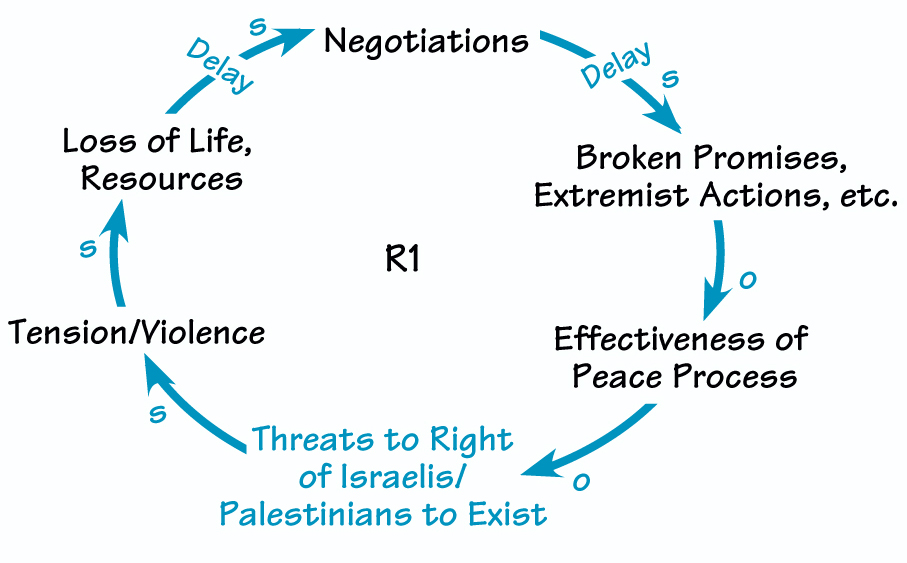

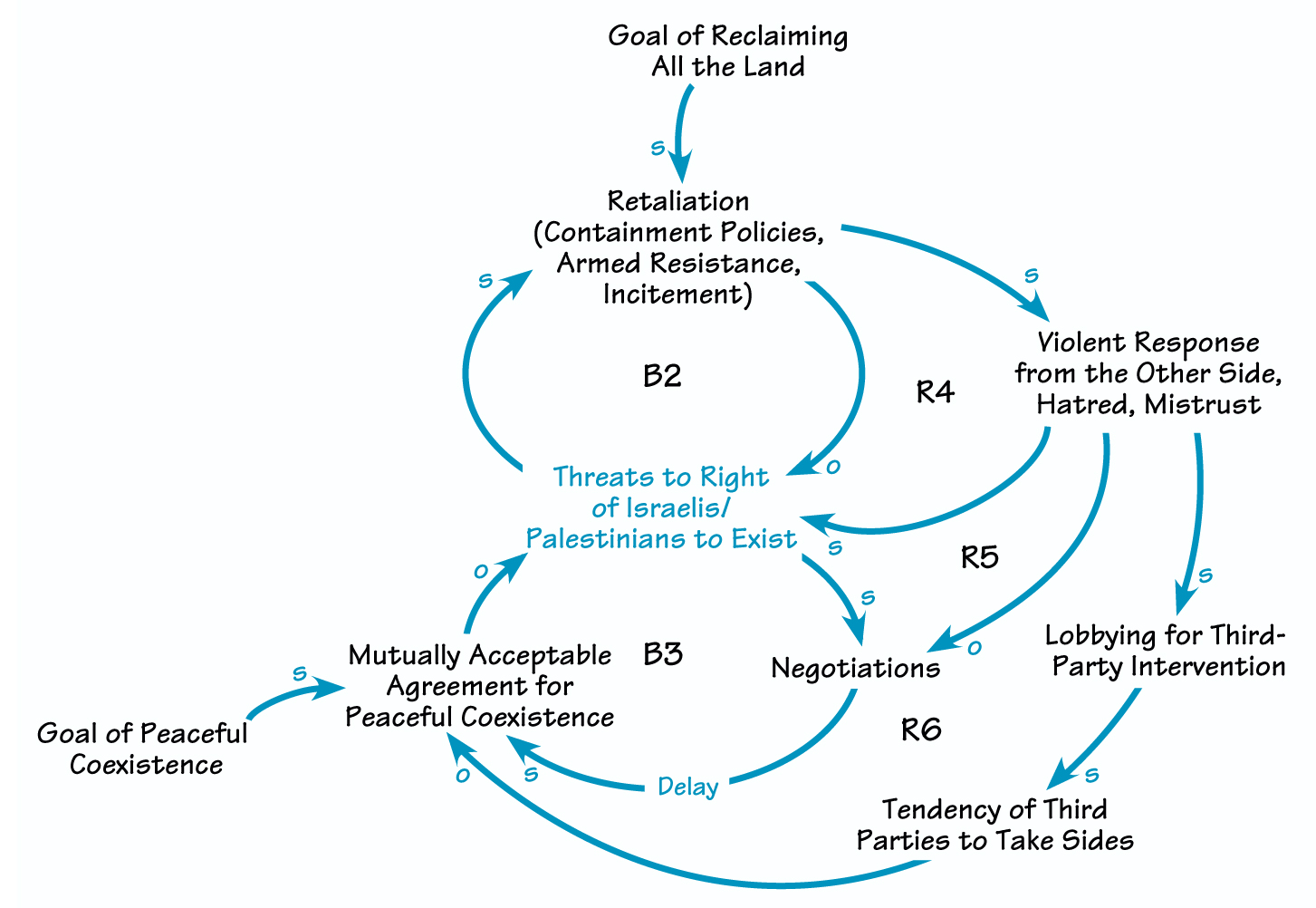

2. The Tension Escalates. Over time, both sides have grown increasingly dependent on the strategy of retaliation (see “Dependence on Retaliation”). As one side gains a temporary advantage in its battle for legitimacy, the other acts to regain its own advantage. This pattern of escalation manifests in several ways:

- Israel uses military force and constraints on Palestinians’ movement to retaliate for Palestinian actions.

- Palestinians perpetrate violence against Israeli citizens and encourage their people to deny Israel’s right to exist.

- Each side perceives itself as a victim of the other’s aggression instead of seeing how its own actions contribute to the escalating conflict.

In the short term, each group’s strategies to claim its right to exist succeed. Through their containment policies, Israelis reaffirm, “They cannot force us to leave.” Through violent resistance, Palestinians reaffirm, “They will have to take us seriously.” In the long term, however, both sides fail to see the unintended consequences of their actions: They only increase the feelings of threat experienced by the other side, motivating them to act to reduce these attacks and regain their own sense of legitimacy—even as the loss of life and other costs increase.

For example, Israeli actions have increased economic hardship for Palestinians, deepened their feelings of humiliation and indignation, and led to significant losses of life. (According to U. N. estimates, as of December 2001,15 months after the Al Aqsa Intifada began, approximately 800 Palestinians had been killed, and the Palestinian economy was losing $11 million per day. The death toll has climbed with the recent escalation in violence on both sides.) In response, the Palestinians have become more unified and motivated to take even bolder actions; suicide bombings now occur several times a week. In the words of Jibril Rajoub, head of preventive security for the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, many Palestinians feel that “We have nothing left to lose.” In turn, greater resistance has only served to increase Israel’s determination to defend all of the land. An editorial in the Jerusalem Post states, “What must be defeated is the Hezbollah model—the idea that if you kill a few Israelis for long enough, they will get tired and leave.”

DEPENDENCE ON RETALIATION

Both sides have grown increasingly dependent on retaliation in response to threats to their right to exist (B2). In the long term, this strategy only increases the feelings of threat experienced by the other side (R4) and undermines the fundamental solution—negotiations for peaceful coexistence (R5). Third parties contribute to the conflict when they take sides (R6).

This cycle of retaliation is further compounded by the fact that both parties perceive themselves as victims of forces beyond their control. Palestinians claim they are victims of Israeli aggression; Israelis feel besieged by the entire Arab world. Each side emphasizes how the other’s actions hurt it while ignoring how its own actions hurt the other party. Because the self-perception of powerlessness is so deeply ingrained in the psyches of both peoples, it is very difficult for them to perceive that they have now become aggressors as well as victims. Each fails to see their own responsibility for increasing the levels of threat they experience—and fails to consider actions they might take to reduce these threats.

3. Pressure Leads to Negotiations. Only when the loss of life and resources incurred by both sides reaches a critical point do people begin to question the viability of resolving the conflict by force. In tandem with changes in the larger geopolitical forces affecting the region, this questioning eventually prompts a renewal of peace negotiations. We have seen this cycle occur several times, for example, when the failure of the first Intifada and the fall of the Soviet Union led to meetings in Madrid in 1991 and the Oslo Accords in 1993, and when, after the assassination of staunch peace advocate Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 and the extremism of the hardline government of Benyamin Netanyahu, Israelis elected the more liberal Barak in 1999.

Many on both sides believed they had reached a potential breakthrough in negotiations when, at Camp David in the summer of 2000, Barak offered the Palestinians most of the West Bank and East Jerusalem—an offer that Arafat rejected. Even after the Camp David meeting dissolved and the Al Aqsa Intifada began, parties on both sides continued to meet. At Taba in January 2001, they came very close to an agreement that many on both sides believe will eventually be the basis for a negotiated settlement.

4. Peace Efforts Break Down. Despite signs of a significant breakthrough on the most difficult issues, all peace efforts have inevitably broken down. Long-term dependence on destructive ways of resolving the conflict have led to profound mistrust and hatred. This hostility undermines the peace process in two fundamental ways. First, it decreases commitment by both sides to pursuing peaceful coexistence and strengthens people’s dreams of recovering all of the land. Second, it weakens the trust-building process by leading to a series of conditions, mixed messages, and broken promises.

Because of the build-up of mistrust and hatred, many people believe that a peace agreement can only be reached with the aid of international brokers—both at the negotiating table and on the ground thereafter. However, using brokers is problematic because each group tries to get the third parties to take sides—something the international community is not immune to doing. The United States has historically sided with Israel, and the European Community has generally sided with the Palestinian cause. As a result, both Israelis and Palestinians succeed in deflecting responsibility for the conflict and perpetuating the cycles of blame and victimization, rather than being accountable for their own destructive actions.

Extremist Actions

Remarkably, despite all of these barriers, at times the peace process appears to move forward. After the Oslo Accords, Israel ceded parts of the West Bank to Palestinian control, and the Palestinian leadership arrested Palestinian extremists. Informal dialogues as well as more formal negotiations on common issues such as water management grew, and people on both sides believed that peace could be achieved. Even after the Al Aqsa Intifada had raged for nearly a year, the worldwide coalition developed after September 11 to fight global terrorism gave both Israelis and Palestinians hope that the international community would finally succeed in getting them to agree to a sensible and honorable peace.

But no matter how intelligently and well designed a peace agreement may be, some people will perceive themselves as losers. Effective compromise is likely to mean that Israel will surrender most of the West Bank and all of Gaza and accept some symbolic right of return for Palestinians. In exchange, the Palestinians would recognize that Israel has the right to retain control over the remainder of the territory. In this scenario, Israeli settlers and right wingers would have to give up their homes and their dream of control over the promised lands of Judea and Samaria. Palestinian losers would include radical groups and refugees who have survived in terrible conditions in camps and who still dream of reclaiming all of the former Palestine.

To extremist groups on both sides, a compromise is unacceptable. When peace appears too near, they strike the ultimate blow to its realization. For example, the murder of nearly 30 Palestinians in a mosque by Israeli settler Baruch Goldstein is one of several Israeli actions that disrupted progress on the Oslo Accords. Bombs set off by the radical Palestinian group Hamas in 1996 are partly to blame for the failure of Israeli Labor Party leader Shimon Peres to get elected and fulfill Rabin’s promise of peace.

Extremist violence does not need to be directed against the other side in order to be effective. A Jewish settler assassinated Rabin, perhaps Israel’s most effective advocate for peaceful coexistence. Palestinian extremists have also murdered fellow Palestinians who pursue coexistence as a legitimate option. Nor do extremists need to act violently to be effective; they can also make unreasonable demands. For example, many believe that Arafat’s insistence on a full right of return for Palestinian refugees to Israeli territory was the breaking point in the July 2000 Camp David talks. Others view Sharon’s insistence on a total cessation of Palestinian violence in order for peace talks to resume as an impossible standard intended specifically to stall further negotiations.

Whatever the method used, the actions of an extreme few seem to successfully undermine compromises that would benefit the majority of both peoples. Such events set off additional rounds of blocking, incitement, and fighting that only serve to build further mistrust and hatred and undermine negotiations.

Systemic Solutions

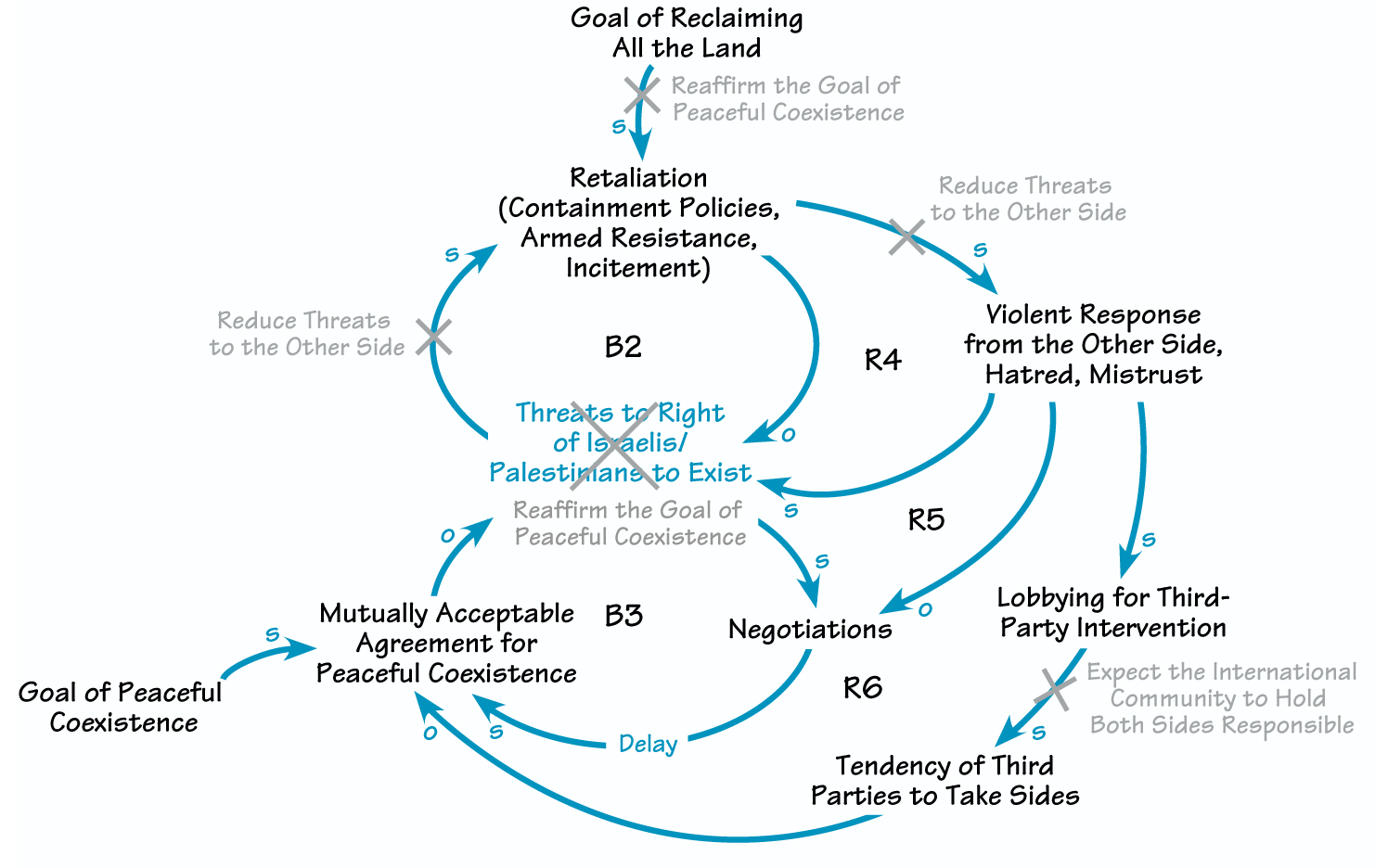

What does this analysis suggest in terms of systemic solutions to resolve the conflict? I believe that both the protagonists and third parties must:

- Accept that their current solutions are a dead end and hurt themselves—not just the other party.

- Think systemically before taking new action.

- Reduce threats to the other side—and be willing to take risks for peace.

- Reaffirm the goal of peaceful coexistence, reiterating that both sides have rights to live in viable states in former Palestine—and that both grieve the dream of recovering all of the land.

- Expect the international community to hold both sides responsible for their actions—and give up favoring either one.

POSSIBLE LEVERAGE POINTS FOR CHANGE

Successful interventions often involve breaking a link between variables or changing variables. Before beginning to intervene in this long-standing cycle of violence, Palestinians, Israelis, and the international community need to think systemically and accept that current approaches are a dead end.

Accept That Current Solutions Are a Dead End. While some observers do recognize the vicious cycle in which both sides are caught up, most Palestinians and Israelis are unable to see how their own actions hurt their cause. Currently, each side tends to hear the solutions offered by third parties as actions that the other side should take but won’t; thus, current solutions have reached a dead end. By taking a systemic perspective on the ongoing conflict, perhaps each group will be able to see actions it can take in its own best interests. To that end, both Israelis and Palestinians must become aware that:

- They are weakening their own positions through actions that gain them temporary advantage only to leave them more threatened and frustrated in the long term.

- Neither side can succeed in claiming its own right to exist without also having to acknowledge this right for the other.

- Any actions that don’t acknowledge each other’s rights will lead only to greater threats to Israeli security and Palestinian sovereignty—and to greater losses of life and material resources on both sides.

- Because each side is an aggressor as well as a victim, it can do more than it believes, individually and in cooperation with the other party, to change the situation.

Whatever past injustices have led Israelis and Palestinians to this point, in the present they are both responsible for their actions. Both have the opportunity to act in wise ways that ensure a more creative and satisfying future for all. To the extent that each group understands how its actions unwittingly undermine its own cause, they can then initiate and implement more sustainable proposals for peace.

Think Systemically Before Taking New Action. Thinking systemically involves:

- Testing the underlying mental models that drive so much of people’s behavior.

- Shifting from the question “Who is to blame?” to “Where is the leverage in the dynamic between the two sides?” Letting go of blame does not necessarily mean letting go of anger, though it does mean finding solutions that create less pain and anger in the future.

- Asking, “What can we do to break the spiral of retaliation and revenge?” While the vicious cycle is now painfully obvious to both sides, what is less clear is that it can only be broken if each side takes its own initiative to act differently.

- Considering the unintended consequences of proposed solutions.

Reduce Threats to Both Sides. Instead of being so concerned about whether or not the other side will change (a source of repeated failures to deescalate the conflict), each side needs to focus on what it can do to initiate change. Additionally, before taking any action, each should consider the following questions:

- What are the benefits of our actions in the short term?

- What are the likely consequences of these actions in the long term?

- How will the other side likely react to our actions?

- What will we do when they react?

- Will our actions and their likely reactions produce the outcome we want?

These questions indicate that the first step each party can take in its own best interest is to reduce threats to the other side. In other words, each side must make more efforts to reduce threats on the ground and not limit its actions to discussions at the negotiating table.

Israel can act in ways that demonstrate respect for the Palestinian people without losing sight of its own security needs. This means freezing investment in settlements and reclamation of land where Palestinians live, eliminating acts of harassment and humiliation that do little to bolster security, and allowing Palestinians to move freely as the violence subsides. Palestinians can reduce both violence and incitement while continuing to claim their right to a state with viable borders. They can engage in nonviolent resistance while validating Israel’s right to exist.

Reducing threats not only minimizes defensive reactions, but it softens the mistrust and hatred that have prolonged the conflict. Doing so will likely make both sides feel more comfortable returning to the negotiating table. Once the two sides reach agreement, they then need to keep the promises they make instead of finding loopholes that only lead to further escalation.

At the same time, each side must be prepared to take risks to achieve peace. Israel must not only insist on creating secure borders, but also be willing to risk that it has both the military strength and moral high ground to thoroughly defend Israeli lives and territory within pre-1967 borders. Palestinians must not only insist on a viable state with contiguous borders within the West Bank and Gaza, but also be willing to risk that they can develop their own state effectively and efficiently. While these risks feel very real to both sides, the risks to safety and sovereignty they currently face are untenable.

Reaffirm the Goal of Peaceful Coexistence. Ultimately, any compromise requires that both sides give up their respective dreams of controlling all of Palestine. Making this choice means preparing people on both sides to accept that they will achieve less than what they really want. It means grieving the loss of the dream and claiming the best that this situation has to offer. It means containing the extremists on both sides and not allowing their actions to deter the compromise that benefits the majority of people on both sides. For Israelis, it means preparing to welcome back the settlers who have risked their lives to populate all of “the promised land.” For Palestinians, it means accepting the Jews’ historical claims to this part of the world and setting realistic expectations for Palestinians’ right of return to what is now Israel.

Both sides need to replace the dream of recovering all of the land with a dream of peaceful coexistence. Palestinians can focus on channeling the determination and education of their relatively young population—as well as support from the international community—into peaceful lives, economic well-being, and global respect. Israelis can focus on directing their enormous creativity and energy toward producing environmental, social, and economic advancements that benefit all of its population.

Expect the International Community to Hold Both Sides Responsible. Third parties drawn into the conflict will only be effective when, rather than taking sides, they hold both sides responsible for the conflict and condition their engagement on actions taken by both to resolve it. Third parties can take four additional actions to support peacemaking:

- Validate the pain and anger experienced by both sides without feeding a cycle of blame and revenge. Empathizing with statements such as “This terrible thing happened to me” can lead to true healing, while buying into accusations such as “They did this to me” only supports further helplessness and reactivity.

- Validate people’s belief that any new peace process within the existing framework is likely to fail. The process will fail as long as each side believes it can take the same actions and get a different result or waits for signs that the other side is changing. However, it can succeed if both sides change their own behavior and trust that the other party will do the same.

- Anticipate and explicitly address the pitfalls of entering the peace process. Acknowledge that, historically, negotiations have been weakened by conditions, mixed messages, and broken promises, and that extremists take actions to undermine agreements when peace appears near. Encourage both sides to address these negotiation issues before they become a problem, contain their extremists, and educate their people to refrain from revenge if the extremists strike.

- Be prepared to provide on-the-ground support. Until now, the international community has been reluctant to commit on-the-ground support to help each side keep the agreements. Given current levels of mistrust and hatred, third-party brokers might need to establish a physical presence as well as provide financial aid to achieve the required changes.

Balance of Power?

Some Israeli and Palestinian reviewers of this work have challenged one particular aspect of the analysis—it assumes that both sides have equal power in and responsibility for the current situation. Clearly, Israel has more power militarily and economically, and Palestinians have suffered more in terms of human casualties and economic hardship. I believe, however, that balance exists precisely because neither side has succeeded in eliminating the claims of the other to the land they inhabit. The ongoing impasse suggests that Palestinians’ strengths in terms of determination, armed resistance, and incitement have compensated for what they lack in other resources. Palestinians also have veto power at the negotiating table, which they used pointedly at Camp David.

Both sides also have external supporters and detractors that appear to balance out their respective power. Israel is strongly supported by the U. S., while it’s criticized internationally for not honoring U. N. Resolution 242 recognizing the West Bank as occupied territory. Its neighbors in the Middle East accept its existence only reluctantly, if at all, while some threaten to destroy it. Moreover, global anti-Semitism still exists, as exemplified by a recent U. N. conference on racism that turned into an almost singular attack on Zionism. Palestinians, on the other hand, receive strong verbal encouragement from their Arab neighbors to fight for statehood—even though these same neighbors treat Palestinians poorly in their own countries and often fail to follow through on financial promises. Most of the official money that sustains Palestinians comes from Europe (and ironically from Israel, when it permits Palestinians to work there). Other Arab leaders fear that if Palestinians were to achieve statehood, it might stimulate popular uprisings in their countries—something that these nations do everything to repress.

A systemic viewpoint of the Israeli-Palestinian situation inevitably points to the interdependent and unintentionally self-destructive nature of both sides’ actions. Each party has a role in creating and perpetuating the conflict, and each must take responsibility for doing what it can to resolve it. Becoming aware of how their own actions unwittingly undermine their effectiveness and accepting the limits of what they can create are essential ingredients for both the Palestinians and the Israelis to achieve the security, respect, and sovereignty that each deserve.

David Peter Stroh (davidpstroh@earthlink.net) is a cofounder of Innovation Associates and a charter member of the Society for Organizational Learning.