I once read a story about a trivia “pack rat,” a man who had spent his entire life memorizing trivia. He knew baseball statistics of every player in the history of the major league. He had memorized the titles, directors, and actors of hundreds of movies. He knew the name of every television show that had ever aired.

But one day he found himself in an awkward predicament — no matter how hard he tried, he could not memorize another bit of trivia. He had finally taxed the limits of his rote memorization capacity. Although he had worked hard at acquiring his stock of trivia throughout his life, he had never considered how he might go about depleting it. He had not learned the fundamentals of accumulator management.

Pack Rats and Nomads

Life can in some ways be viewed as a never-ending task of managing various accumulators. Our pantries, refrigerators, checking accounts, and closets are among the many accumulations we manage daily.

Insurance Business as Accumulation Management

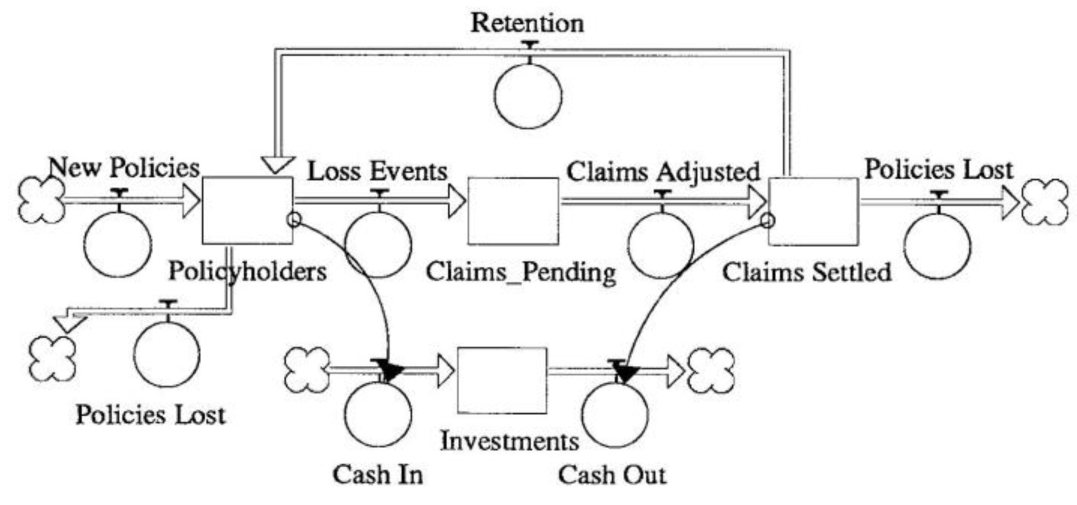

The insurance business can be mapped into a relatively simple diagram that highlights the major accumulators and flows. If we assign numbers next to each accumulator or flow indicating the percentage of organizational resources devoted to it, the diagram can help re-evaluate the organization’s current emphasis.

On one end of the accumulation management spectrum is the pack rat who throws nothing away. On the other end is the “nomad” who makes a virtue of owning no more than what can be packed into one suitcase. In between these two extremes lies the majority of the population who are constantly struggling to maintain the right balance between acquisitions and depletions.

Anatomy of the Accumulator Management Structure

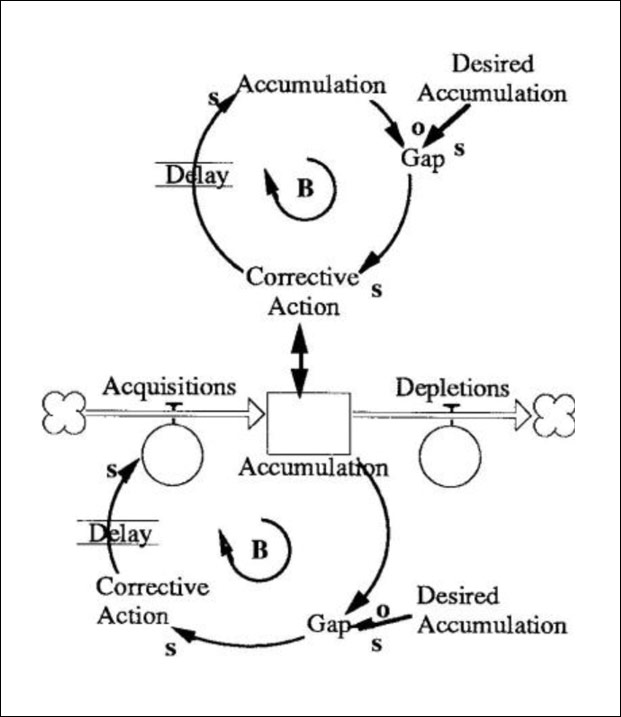

A typical Accumulator Management Structure (AMS) has the following elements: the Accumulation, Acquisitions, Depletions, Desired Accumulation, and a Corrective Action (see “Accumulator Management Structure” diagram). In addition, there is almost always some delay between the Corrective Action and the Acquisition, because it takes time to actually memorize data or clear out the closet once we have decided to do so.

Accumulator Management Structure

In its simplest form, accumulator management can be viewed as a balancing loop with delay (top). A structural diagram (bottom) reveals that the flows controlling the accumulation are acquisitions and depletions.

If managers assign a number next to each accumulator and flow in the diagram to represent the percentage of organizational resources devoted to each, the diagram can highlight which areas receive the largest organizational focus. This exercise can point out any weaknesses in the current organizational emphasis — for example, spending too little time trying to retain current policyholders — and reveal ways in which the company can better serve its customers.

Supply Lines and Delays

If we have direct and immediate control over all the elements in the AMS diagram, managing accumulations would be simple: we would calculate what the depletion rate is, set our desired accumulations accordingly, and implement actions that will immediately result in acquisitions. In our home life we already pretty much follow this pattern. For example, we plan our meals, decide on an appropriate amount of food to have on hand, figure out how long it will be before we run out of certain staples, and go to the grocery store as needed. Unfortunately, things are not that straightforward when we move into the organizational context.

One of the most challenging aspects of managing accumulations within organizations is captured in one word — delays. Identifying and characterizing the nature and source of delays often plays a critical role in managing accumulations effectively. A big part of the problem is that we usually have very little control over the supply line delay.

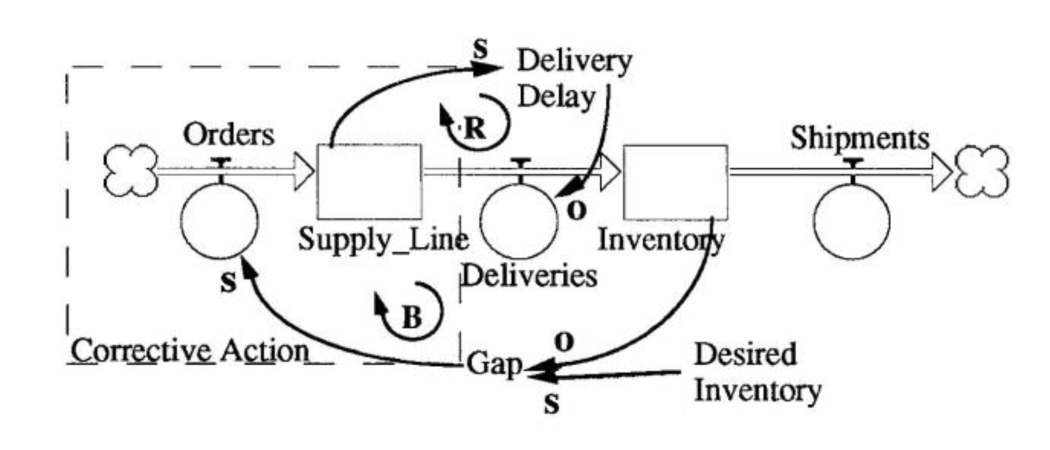

Supply Line and Delay in the Beer Game

The structure of the inventory management system in the Beer Game is similar to the AMS diagram. Understanding the nature and source of delays in a systems—such as the supply line delay above — often plays a critical role in managing accumulations without overcorrecting.

According to MIT Professor John Sterman, when participants try to manage accumulations in the Beer Game they usually run into three common problems. First, they typically underestimate the true length of the delay from the time they order to when they receive the beer and then over adjust their orders — even when they are given full information about the supply line delays. They do not appear to recognize that their ordering decisions affect the length of the supply line delay — that is, the more they order, the longer it takes to receive the beer.

In addition, he found that when people fund it difficult to determine their optimal inventory level, they simply anchor their desired inventory on the initial inventory and adjust from there. This finding highlights the more general tendency people have to anchor on past goals or standards rather than search for better ones.

The third observation is that people generally point to factors outside the system as being responsible for the instabilities they observe in the game. That is, people offer open loop explanations rather than connecting the dynamics back to their own decision making. In fact, the wide oscillations in inventory are actually generated by the decisions they make.

Avoiding the “Pack Rat” Syndrome

If you want to avoid the “pack rat” syndrome, you need to manage the whole Accumulator Management Structure and not just focus on one piece of it. The observations about the difficulties of managing the Beer Game suggests that you should think through the following questions when confronting a typical accumulator management situation: (1) Where are the supply line delays and how are they changing? (2) What factors are determining what Desired Accumulation should be? (3) How do current policies and decisions feed back into this system to produce the results we have observed? The Accumulation Management Structure diagram is a useful starting point to begin addressing these questions.

Further Reading: “Modeling Managerial Behavior: Misperceptions of Feedback in a Dynamic Decision Making Experiment,” by John D. Sterman, Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 3, March 1989.