There is much agreement that one of the key characteristics of the 21st-century organization will be its ongoing ability to learn. In fact, it has been said that the ability to learn will be a major competitive advantage for organizations. These beliefs have generated a frenzy of activity in recent years, as business leaders scramble to figure out not only what organizational learning is, but how to do it.

These activities perhaps contain more optimism than realism. Learning is, at its heart, a complex and difficult process—a source of joy when it works, but a source of pain and tension when it does not. Learning forces us to fundamentally rethink the way we view the world—a process that is difficult in part because our cultural assumptions predispose us to take certain things for granted, rather than to re-examine them continually. Since learning and culture are so closely interrelated, it is incumbent upon us to understand more about the interaction of the two, and to identify, if possible, what elements of a culture might truly facilitate learning to learn.

Two Kinds of Learning

To understand the important role that organizational culture plays in learning, we need to first make a distinction between two types of learning: “adaptive” and “generative.” (The term “generative learning” comes from Peter Senge. However, the same process has been labeled by Chris Argyris and Donald Schön as “double-loop learning,” while Don Michael, Gregory Bateson, and others have identified it as “learning how to learn.”)

Adaptive learning is usually a fairly straightforward process. We identify a problem or a gap between where we are and where we want to be, and we set about to solve the problem and close the gap. Generative learning, on the other hand, comes into play when we discover that the identification of the problem or gap itself is contingent on learning new ways of perceiving and thinking about our problems (i.e., rethinking cultural assumptions and norms).

For example, from an adaptive point of view, we may decide that we have to replace corporate hierarchies with flat networks in order to reduce costs and increase coordination. From a generative point of view, however, we might instead begin by examining our mental models and considering how hierarchies and networks might be integrated into a more effective corporate design. From “either this or that” thinking, we might have to develop the capacity to think about “this and that.”

Two Kinds of Anxiety

The very process of identifying problems, seeing new possibilities, and changing the routines by which we adapt or cope requires rethinking and redesign, because we have to unlearn some things before new things can be learned. Thus, generative learning, by its very nature, asks us to question our mental models, our personal ways of thinking and acting, and our relationships with each other. This deep level of change can produce two kinds of anxiety.

The first is the fear of something new. Instability or unpredictability is uncomfortable and arouses anxiety— what I have called “Change Anxiety,” or the fear of changing—based on a fear of the unknown. Adaptive learning, whether it be in individuals, groups, or organizations, tends toward stability. We seek to institutionalize those things that work. Indeed, it is the stable routines and habits of thought and perception that we call “culture.” We seek novelty only when most of our surroundings are stable and under control.

However, learning how to learn may require deliberately seeking out unstable, less predictable, and possibly less meaningful situations. It may also require perpetual learning, which opens up the possibility of being continually subject to Change Anxiety. This is a situation most of us would prefer to avoid.

But if, as many people anticipate, the economic, political, technological, and sociocultural global environment will itself become more turbulent and unpredictable, then new problems will constantly emerge and past solutions will constantly become inadequate. This brings us to a second type of anxiety, which I call “Survival Anxiety”—the uncomfortable realization that in order to survive and thrive, we must change.

In order for learning to occur, somehow we must reach a psychological point where the fear of not learning (Survival Anxiety) is greater than the fear associated with entering the unknown and unpredictable (Change Anxiety).

REDUCING CHANGE ANXIETY

- Provide psychological safety—a sense that something new will not cause loss of identity or of our sense of competence.

- Provide a vision of a better future that makes it worthwhile to experience risk and tolerate pain.

- Provide a practice field where it is acceptable to make mistakes and learn from them.

- Provide direction and guidance for learning, to help the learner get started.

- Start the learning process in groups, so learners can share their feelings of anxiety and help each other cope.

- Provide coaching by teaching basic skills and giving feedback during practice periods.

- Reward even the smallest steps toward learning.

- Provide a climate in which making mistakes or errors is seen as being in the interest of learning—so that, as Don Michael has so eloquently noted, we come to embrace errors because they enable us to learn.

As teachers, coaches, and managers, how then do we make sure that Survival Anxiety is greater than Change Anxiety? One method is to increase Survival Anxiety until the fear of not changing is so great that it overwhelms the fear of changing. We can do this by threatening the learner in various ways, or by providing strong incentives for learning. For example, if employees feel that they will not get promoted in the organization if they don’t use electronic mail or conduct their meetings with the latest groupware, it would seem logical that they would want to keep up with new technology.

However, humans don’t always do what logic dictates. If an employee’s Change Anxiety becomes too high, he or she may instead become defensive, misperceive the situation, deny reality, or rationalize his or her current behavior. Change agents often come up against this type of resistance to organizational change and retreat to the rationalization that “it’s simply human to resist change.”

Perhaps a more effective way to initiate change is to reduce Change Anxiety so that it is less than Survival Anxiety. We can do this by concentrating on making the learner feel more comfortable about the learning process, about trying new things, and about entering the perpetual unknown (see “Reducing Change Anxiety”).

Addressing the anxiety caused by learning and change is certainly a good way to begin the learning process, at least at the individual and small group levels. But how can we apply the generative learning process across various organizational boundaries and sustain the learning process over longer periods of time? This requires the creation of an organizational culture that supports perpetual learning at the individual, group, and organizational levels.

A Learning Culture

What would such a culture look like? Learning cultures share at least even basic elements:

- A concern for people, which takes the form of an equal concern for all of the company’s stakeholders—customers, employees, suppliers, the community, and stockholders. No one group dominates management’s thinking because it is recognized that any one group can slow down or destroy the organization.

- A belief that people can and will learn. It takes a certain amount of idealism about human nature to create a learning culture.

- A shared belief that people have the capacity to change their environment, and that they ultimately make their own fate. If we believe that the world around us cannot be changed, what is the point of learning to learn?

- Some amount of slack time available for generative learning, and enough diversity in the people, groups, and subcultures to provide creative alternatives. “Lean and mean” is not a good prescription for organizational learning.

- A shared commitment to open and extensive communication. This does not mean that all channels in a fully connected network must be used all the time, but it does mean that such channels must be available and the organization must have spent time developing a common vocabulary so that communication can occur.

- A shared commitment to learning to think systemically in terms of multiple forces, events being over-determined, short- and long-term consequences, feedback loops, and other systemic phenomena. Linear cause-and-effect thinking will prevent accurate diagnosis and, therefore, undermine learning.

- Interdependent coordination and cooperation. As interdependence increases, the need for teamwork increases. Therefore, organizations must share a belief that teams can and will be effective, and that individualistic competition is not the answer to all questions.

Inhibitors to Learning

Culture is about shared mental models—shared ways of perceiving the world, sorting out that information, reacting to it, and ultimately understanding it. Therefore, in order to understand what prevents us from creating learning cultures, we need to explore the shared assumptions that act as inhibitors to learning. If we look at western (particularly U.S.) organizational and managerial cultures, there are several shared assumptions or myths that prevent organizations from developing the kind of learning culture I have described.

Generative learning, by its very nature, asks us to question our mental models, our personal ways of thinking and acting, and our relationships with each other.

Human history has left us with a legacy of patriarchy and hierarchy, and a myth of the “superiority” of our leaders based on the view of the leader as warrior and protector. This has created almost a state of “arrested development” in our organizations, in the sense that we have very limited models of how humans can and should relate to each other in organizational settings. The traditional hierarchical model is virtually the only one we have.

One consequence of this rigid model is that managers start with a self-image of needing to be completely in control—decisive, certain, and dominant. Neither the leader nor the follower wants the leader to be uncertain, to admit to not knowing or not being in control, or to embrace error rather than to defensively deny it. Of course, in reality leaders know that they do not have all of the answers, but few are willing to admit it. And since subordinates demand a public sense of certainty from their leaders, they reinforce this facade. Yet if organizational learning is to occur, leaders themselves must become learners, and in that process, begin to acknowledge their own vulnerability and uncertainty.

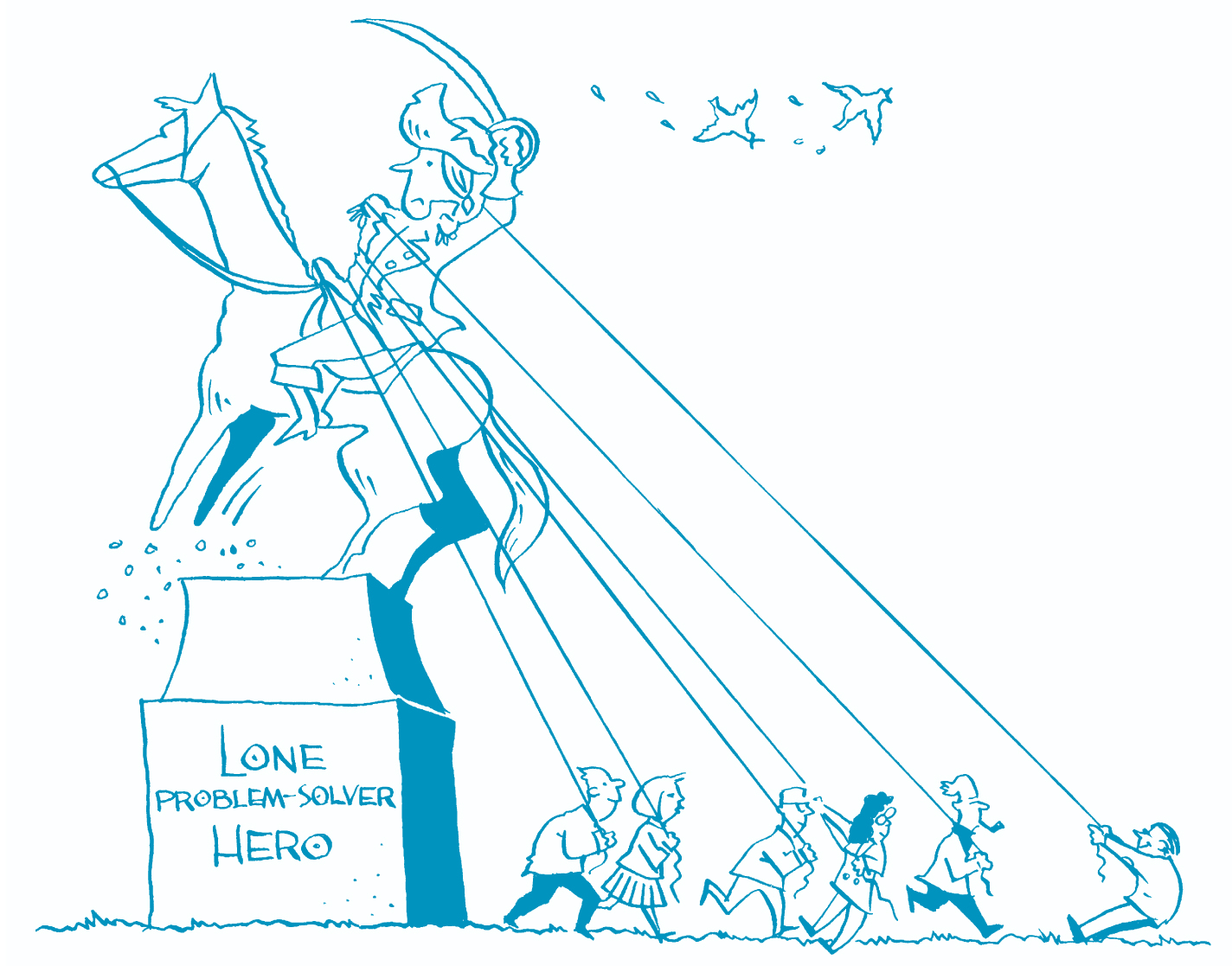

In the U.S., we have the additional cultural myth of “rugged individualism” that makes the lone problem-solver the hero. The interdependent, cooperative team player is not typically viewed as a “hero.” In fact, competition between organizational members is viewed as natural and desirable, as a way to identify talent (“the cream will rise to the top”). After all, if teamwork were more natural, would it be such a popular topic in organization development literature? For the most part, teamwork is viewed as a practical necessity, not an intrinsically desirable condition.

Another myth that has developed among managerial circles might be called the “divine rights of managers.” Management is believed to have certain prerogatives and obligations that are intrinsic and are, in a sense, the reward for having worked oneself up into the management ranks. The relatively young and egalitarian social structure of the U.S. exacerbates this problem by emphasizing achievement over formal status. We have no clear class structure that provides people with a clear position in society. Hence, they often rely instead on earned position, title, and visible status symbols (cars, homes, etc.) as a way of displaying rank. The competition based work hierarchy then ultimately becomes the main source of security and status, and higher level managers are expected to act in a more decisive and controlling manner to express that status.

Another barrier to learning is the fact that work roles and tasks are very compartmentalized in the U.S., and are separated from family and self-development concerns. These roles are expected to be treated in an emotionally neutral and objective manner, which makes it very hard to examine the pros and cons of organizational practices that put more emphasis on relationships and feelings. Even talking about anxiety in the workplace is often taboo. This creates an inherent dilemma: how can we effectively address learning-produced anxiety if we cannot discuss it?

Within the work context we have the further problem that task issues are always given primacy over relationship issues. Everyone pays lip service to the notion that people and relationships are important, but our society’s basic assumptions are that the real work of managers lies with quantitative data, money, and bottom lines. Within this framework, people can seem like nothing more than another resource to be “deployed” or “controlled.” If we have any doubts about the reality of this viewpoint, consider how many performance appraisal systems tend to reduce performance to numbers rather than deal with qualitative descriptions of performance and leadership potential.

In reality, leaders know that they do not have all of the answers, but few are willing to admit it. And since subordinates demand a public sense of certainty from their leaders, they reinforce this facade.

The bias toward viewing organizations in quantitative terms shows up most clearly in graduate schools of business, where the popularity of quantitative courses in finance, marketing, and production is much greater than qualitative courses in leadership, group dynamics, or communication. Associated with this myth that management is only about “hard” things is the focus on short time horizons. Driven by our current reporting systems, managers learn early on to pay closer attention to the short-term trends in their financial numbers than to the long-term morale or development of their employees. Creating an environment for learning is a long-range task, yet few managers feel that they have the luxury to plan for people and learning processes.

The combination of this task focus, preference for hard numbers, and short-run orientation all conspire to make systems thinking difficult. Systems are ultimately messy, and they cannot really be understood without taking a longer range point of view, as system dynamics has convincingly demonstrated.

Articulating the Challenge

Creating a learning culture from this set of assumptions is very difficult. It is one thing to specify what it will take for us to become effective learners; it is quite another thing to get there, given these strong cultural inhibitors. But the first and most necessary step is always a frank appraisal of reality. If we understand our cultural biases, we can either set out to overcome them slowly, or, better yet, figure out how to harness them for more effective learning.

But we first must acknowledge the difficulty of our task. Culture is about shared tacit ways of being. Because it operates outside of our awareness, we are often quite ignorant of the degree to which our culture influences us. Therefore, we cannot expect that we can just set about to create whatever culture we want, as if it were the same as creating espoused principles and values. Only shared successes in using a new way of thinking, perceiving, or valuing will create this new approach, and that takes time.

CULTURAL INHIBITORS TO LEARNING

- Myth that leaders have to be in control, decisive, and dominant

- Myth of “rugged individualism”

- Shared belief in managerial prerogatives—the “divine rights of managers”

- Belief that power is “the ability not to have to learn anything”

- Achievement as the primary source of status in society

- Compartmentalization of work from family and self

- Belief that task issues should override relationship concerns

- Myth that management is about “hard” things (money, data, “the bottom line”) versus “soft” issues (people, groups, and relationships)

- Bias toward linear, short-term thinking versus systemic, long-term thinking

FOR FURTHER READING

Organizational Culture and Leadership, by Edgar H. Schein, 2nd Edition, San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1992, and “How Can Organizations Learn Faster: The Challenge of Entering the Green Room,” by Edgar H. Schein, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 34(2),Winter 1993.

I believe one mechanism by which cultures change is to re-prioritize some of the shared assumptions that conflict with others. For example, as we discover that competition and rugged individualism fail in solving important problems, we will experiment more with other forms of organizing and coordinating. Initially we may do it only because it is pragmatically necessary. But gradually we will discover the power of relationships and teams to complete tasks more effectively and to improve learning. This “proactive pragmatism” will eventually force us to create a learning culture and, in that process, produce new and quite different 21st century organizations.

Edgar H. Schein is Sloan Fellows professor of management emeritus and a senior lecturer at the Sloan School of Management. He chairs the board of the MIT Center for Organizational Learning and is the author of numerous books on organization development.

Editorial support for this article was provided by Colleen Lannon.