We are in the midst of dramatic changes that are redefining and reshaping our world. Western Europe is consolidating into one common economic market. Eastern Europe is being integrated into the western fold. The Soviet Union is disintegrating, with new sovereign states emerging in its place. The role of the U.S. as the dominant economic engine of the world is diminishing while Japan ascends in its place. This is a unique time of opportunities and challenges. How well we respond to them will have repercussions well into the next century.

The theme of the 1991 Systems Thinking in Action Conference, “Building a Foundation for Change,” proposed a way to address the challenges that lie ahead. Both keynote speakers, Peter Senge and Jay Forrester, focused squarely on the critical issue of building capabilities and understanding that will endure throughout the turbulence that accompanies such periods of great change.

“We are embarking on one of the great frontiers of human endeavor…I see the frontier for the next 50 to 100 years as being a greater understanding of our social and economic systems.”

New Frontiers

“We are embarking on one of the great frontiers of human endeavor — similar to the founding of nation-states, the exploration of the surface of the earth, and the pursuit of scientific and technical knowledge,” declared keynote speaker Jay W. Forrester. “I sec the frontier for the next 50 to 100 years as being a greater understanding of our social and economic systems.”

The timing is auspicious, according to Forrester, because the economy is in the midst of a long wave downturn that will spark fundamental changes in our society (see “Not All Recessions are Created Equal,” February 1991 for more on the long wave and the current recession). “Long wave downturns are windows of opportunity for great social and economic change,” he explained. “Old methodologies have been overdone and overbuilt, and the institutions behind them have been swept away. The public is looking for change. During downturns, foundations are laid for new ideas and methodologies that will flourish during the next upturn.”

Over 250 people from across the U.S. and the globe came together for the conference to hear Senge’s and Forrester’s context-setting remarks, acquire systems tools and techniques for developing new skills, and learn from the experience of managers who have been on the forefront of building their companies’ foundations for change. Summaries of both keynote speeches follow.

Peter M. Senge — Transforming the Practice of Management

I think the primary institutional contexts that we need to consider are the world of management and the world of public education — the two primary institutions in our society. They represent fundamental areas for profound and extensive innovation.

Focusing on the corporate world, let me summarize what I see happening as a paradigm shift from the resource-based organization to the knowledge-based organization. According to Peter Drucker, there have been two previous major changes in the evolution of the organization: first, at the turn of the century, when management became distinguished from ownership; and then in the 1920s, when fundamental changes at DuPont and General Motors introduced the command and control organization of today. “Now we are entering a third period of change,” writes Drucker. “A shift from the command and control organization, the organization of departments and divisions, to the information-based organization, the organization of knowledge specialists.”

The evolution of the Total Quality movement in Japan is further evidence of a growing shift toward managing knowledge. The foundation of the first wave of quality management was in statistics. However, Dr. Edwards Deming, “father of Japanese management” has taken to saying lately that statistics is only 2% of the work. The new book he is working on crystallizes the essence of his management philosophy around four points. Interestingly, the first of Deming’s four cornerstones is appreciation of a system. Similarly, the second wave of Total Quality is focusing more on the area of linguistics and anthropology, because the world of management is the world of ideas. If the work of the front line of an organization is to continually improve the physical processes, then perhaps the work of management is to continually enhance the base of knowledge.

The Shift Toward the Knowledge-Based Organisation

Multi-dimensional Aspects

An article in the most recent issue of the Harvard Business Review, written by Ikujiro Nonaka, summarizes quite well a variety of trends which are part of this shift. In his article, “The Knowledge-Creating Company,” he describes what this type of organization is like: “The centerpiece of the Japanese approach is the recognition that creating new knowledge is not simply a matter of processing objective information. Rather, it depends on tapping the tacit, and often highly subjective insights, intuitions and hunches, of individual employees and making those insights available for testing and use by the company as a whole.”

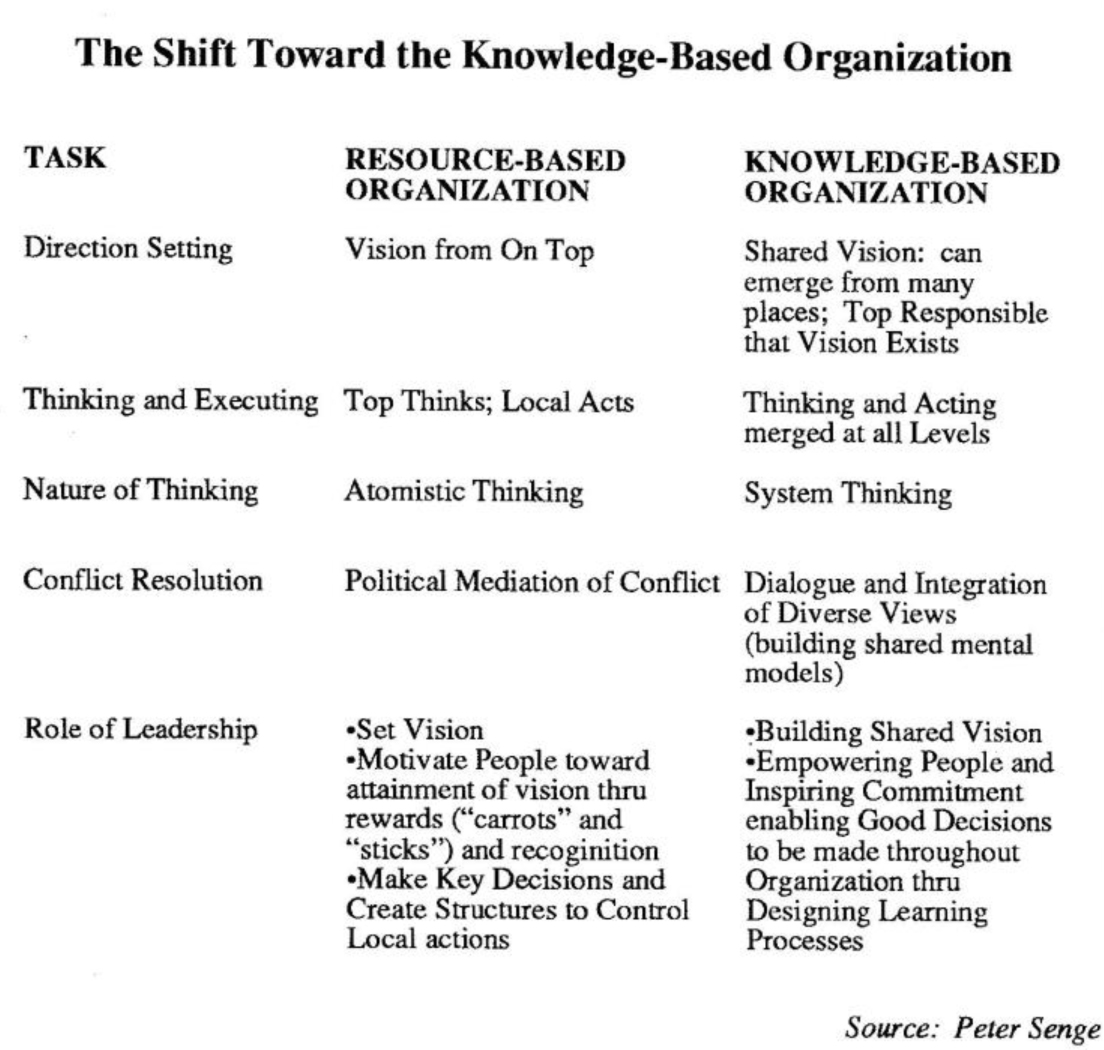

In characterizing the multidimensional aspects of the shift toward the knowledge-based organization, let me contrast five basic tasks at the resource-based organization and the knowledge-based organization: direction setting; thinking and executing; the nature of thinking; conflict resolution; and the role of leadership (see side-bar for an overview).

- Direction Setting and Thinking and Executing. The key to success in the authoritarian, traditional organization is to have a few great thinkers at the top, design some good control systems throughout the organization, and get some good actors at the local level. The top thinks and the local acts. That’s the essence of a traditional organization.

In the knowledge-based organization, shared vision emerges from all levels. The responsibility of top management is to articulate a vision for the company that is broad enough so that workers can interpret and add to that vision, giving them the freedom and autonomy to set their own goals which will put that vision into action. Within this framework, thinking and acting can be merged at all levels of the organization.

- Nature of Thinking. One of the central issues in the shift toward the knowledge-based organization is how power and authority will be distributed. Tight central control is not effective for working in a complex system. When you have people throughout an organization making important decisions, it’s absolutely critical that those people have some contextual knowledge or understanding of how their decisions affect others. Atomistic Winking, the hallmark of the resource-based organization, must give way to an understanding of the whole system. If we are going to distribute power and authority throughout the organization, we must also develop the necessary skills and capabilities for people to use that power and authority wisely.

- Conflict Resolution. In the traditional model, mediating disputes usually means “the biggest stick wins.” In the corporation of the future, the emphasis must be on integrating diverse views and building shared mental models. The great range of differing perspectives and mental models in a corporation might seem like a big problem. In fact, it can be a rich source of new knowledge if a company knows how to challenge employees to continually examine their fundamental assumptions.

- Role of Leadership. The fundamental task of the leader in the knowledge-based organization is to create conditions so that good decisions can be made throughout the entire organization. It is no longer enough to have great thinkers at the top who set • direction, motivate people, and make important decisions. In the corporation of the future, thinking and acting must occur at all levels. For this to happen, the key questions we need to address are: How do we design the learning processes? What are the tools we need? And what are the ways in which we can literally build shared knowledge so we can enable good decision making throughout the organization?

Building a Foundation

If we really accept this paradigm shift as something that is occurring, we need to ask ourselves some questions. From the standpoint of an individual organization, do we want to ignore it? Do we want to get dragged along kicking and screaming? Or do we want to be a leader, and be out on the leading edge helping to create that new model?

I propose four “levels of attention” that we must focus on to build a foundation for such an organization: philosophy, attitudes and beliefs, skills and capabilities, and tools and artifacts. Philosophy is the vision, values, and sense of purpose that we articulate. Attitudes and beliefs are those values that reside more at the tacit or unconscious level Artifacts, a term used by Buckminster Fuller, means those tools which, in helping us deal with practical and important issues, can shift our ways of thinking and interacting and actually influence and improve our skills and capabilities.

The greatest leverage lies in focusing both on the level of philosophy and the level of tools. I think the best strategy for building such an organization is to build from the top down and the bottom up simultaneously. Wherever I see an organization, West or East, that’s really made significant progress, there is a significant amount of tension on both levels.

“The fundamental task of the leader in the knowledge-based organization is to create conditions so that good decisions can be made throughout the entire organization.”

Jay Forrester — Education into the 21st Century

Our educational system is unrealistic in almost every way. Students work on solving problems that are artificial and irrelevant, in which neither the teacher or student is interested, and for which the facts have already been provided. That is just the opposite of the real world, where we start with a problem and then have to search for the necessary information and frame a solution.

The failure of our educational system has brought a great national lamenting, as well as many proposed solutions. A recent Fortune magazine, for example, listed over 100 companies that have donated money to reforming the schools. But the amount of money being given is relatively very small, and the tasks that the money is being earmarked for amount to doing more of what is already clearly not working. It is my intention to give you a glimpse of how the field of system dynamics can address some of the underlying reasons why education is not working and provide a framework that has great power, persuasiveness, and relevance for changing our current educational situation.

A New Framework

System dynamics turns upside down the American theory of education. In traditional education, children start out by learning facts. They then progress through learning how to analyze and break down problems, and then finally to synthesis — putting it all together.

System dynamics places synthesis at the beginning of the educational sequence. By junior high school, students already possess a wealth of facts about interpersonal relations, family life, community, and school. What they need is a framework into which those facts can be fitted. System dynamics simulation models allow the students to learn facts within the larger context of how the dynamics will play out in the real world.

Learner-Directed Learning

Currently there are probably about 30 high schools with substantial activity in bringing system dynamics simulations into the classroom, and about 300 schools that are doing something in this area. The greatest progress is being made in those schools where system dynamics is being used in conjunction with another important concept — learner-directed learning.

With learner-directed learning, students take on a substantial responsibility for what they learn and how they learn it. Operationally, this means that students work together in teams of two or three on a given project, while the teacher plays the role of a coach and advisor — someone who inspires and encourages them. This gives the 7th or 8th grade classroom the atmosphere of a research laboratory.

There seems to be no correlation between a student’s previous academic standing and his or her ability to do well in the new environment. Some students who have seemed “backwards” in the traditional classroom — who have had difficulty learning through memorizing facts or listening to lectures — may have a very keen understanding of how things interrelate and can do very well in the new setting.

In one school in Arizona, for example, an English teacher has the bottom-third track of students. Using the STELLA”‘ software by High Performance Systems (Hanover, NH), she created a system dynamics simulation of the psychological dynamics in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. For the first time, students began to discuss and debate issues among each other. They argued over which one of them was like which character in the play, and what ordinary people would have done in Hamlet’s shoes. They asked the teacher for quantitative changes in the character of an actor in the computer simulation so they could see who got killed instead. Those students are now going around asking why they can’t do similar projects in other classrooms, and they are starting to see themselves as the educational innovators in the school.

Innovation in Orange Grove

Probably the most advanced work with system dynamics and learner-directed learning has been taking place at the Orange Grove Middle School in Tucson, AZ. My mentor at MIT, Dr. Gordon Brown, has acted as a “citizen champion,” bringing system dynamics into the local school system. He first introduced one of the biology teachers at Orange Grove, Frank Draper, to the STELLA software. Frank began using the software to develop projects in his class, with some very exciting results. Two-thirds of the way through the semester, his class had already covered all of the required material for the semester. Because there had been so much excitement, dedication, and accelerated learning going on, the students absorbed the material much faster than ever before.

It was the first time the school had seen twelve- to fourteen-year-old students who wanted to come into school early or stay late to work on their simulations. Even without written assignments, the students would spend weekends researching information they would need for their next project. Discipline problems practically disappeared.

“It was the first time the school had seen twelve- to fourteen-year-old students who wanted to come into school early or stay late to work on their simulations.”

Since then, 200-300 students have been taught using this approach and teachers have seen an order of magnitude improvement in their abilities. As a sign of the school district’s further commitment and confidence in system dynamics and learner-directed learning, last year the district passed a $30 million bond issue to build a new high school which will be organized and taught along the ideas that have been pioneered in the junior high school.

Building a Network

Most schools that are working with system dynamics are isolated from one another. They don’t have knowledge of other programs being developed or work being done in other schools. They need the inspiration of knowing that a growing community of people are all working toward common goals. Programs are now starting that will support these pioneering schools and provide educational materials.

At MIT, I work with a group of undergraduates who are developing materials that can be used in high schools and junior high schools. They have been working with teachers in the Cambridge Rindge and Latin high school in Cambridge, MA as a field laboratory for developing and testing new materials. Also, John R. Bemis of Concord, MA, has made a very generous donation to set up an office that will act as an information interchange among schools that are pursuing this field. Called the Creative Learning Exchange, it will solicit material being developed in various places, reproduce it, and send it out to the schools.

Time Frame

I believe it will probably take 20 years for these ideas to be fairly widely embedded in the schools. It will be another 20 years after that for the students who have gone through these schools and learned the systems viewpoint to become active in politics and corporations. So at the very least we are talking about a forty-year time horizon.

Building any sort of a new foundation takes a lot of investment in time and energy. I don’t see the forty-year time horizon is anything to be pessimistic about. It’s a challenge, an opportunity. Along the way there will be many exciting discoveries, as there has been with the exploration of past frontiers.