Susan is a task manager in an international development bank who finds herself ceaselessly pulled between satisfying client expectations on individual country projects and participating in global communities of practice designed to enhance the bank’s technical knowledge. She often finds that one of her responsibilities must take a lower priority than the other, even though both are equally important.

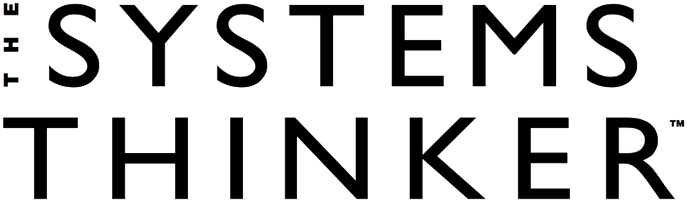

STRESSING A COMMON CORRECTIVE ACTION

The need to achieve two different goals puts pressure on the organization to simultaneously take more (B1) and less (B2) of an action that affects performance relative to both goals. Given the impossibility of satisfying both conditions at once, the organization usually achieves one objective at the expense of another.

Mapping these challenges as competing balancing loops, each with its own goal, can help you better understand the tensions produced by these structures and design strategies to resolve them. This article introduces the feedback processes that define two competing-goals structures and offers some tips for managing the resulting dynamics.

Torn Between Two Goals

There are two basic ways in which conflicting goals manifest themselves. In the first, the need to achieve two different goals puts pressure on the organization to simultaneously take more (B1) and less (B2) of an action that affects performance relative to both goals (see “Stressing a Common Corrective Action”). Given the impossibility of satisfying both conditions at once, the organization usually achieves one objective at the expense of another.

For example, senior managers under the gun to cut costs decide that the best way to do so is to reduce head-count. At the same time, they continue to send a message that the company’s revenue-generation goals must be met. To fulfill this second goal, line managers actually need more workers, which conflicts with the mandate to cut staff.

As a result of these contradictory demands, companies often let people go only to hire them back as contractors or even full-time employees. When Digital Equipment Corporation first tried to downsize in the late 1980s, it experienced an oscillation in headcount over a period of one year, as competition between the two goals intensified (go to http://www.pegasuscom.com/digital.html for a diagram). The problem was compounded by an implicit assumption in the organization that the way to achieve status was to oversee as many people as possible. The fluctuation produced confusion and mistrust on the part of employees as they questioned the company’s direction.

Trying for Both . . . and Getting Neither

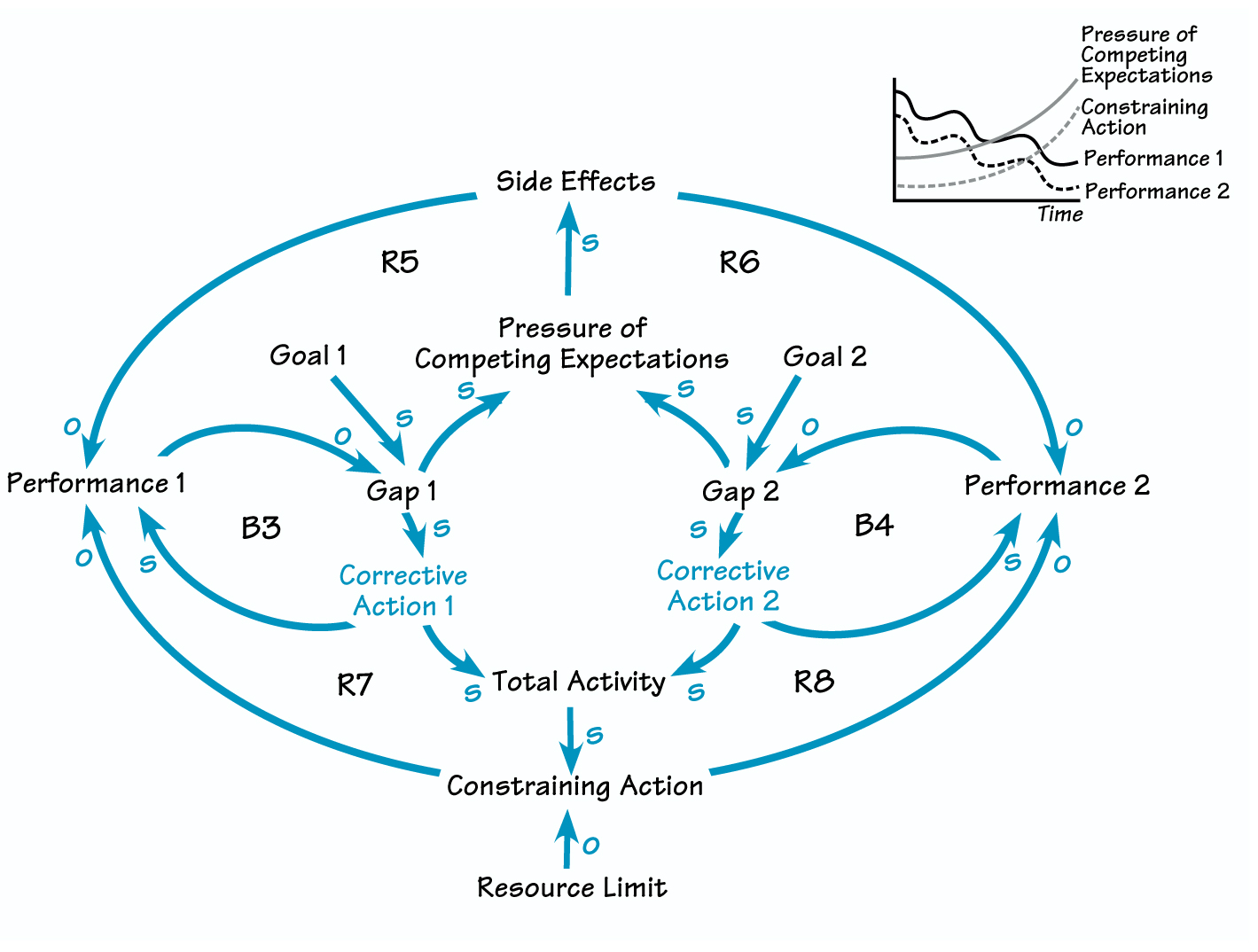

Conflicting goals manifest themselves in a second fundamental way as well. In this case, trying to achieve both goals simultaneously undermines people’s ability to achieve either goal (see B3 and B4 in “Eroding Ability to Achieve Conflicting Goals” on p. 7). Performance may decline because the pressure of competing expectations produces side-effects such as poor communication, reduced cooperation, and decreased productivity (R5 andR6). The increase in total activity may also become unsustainable as limits on such resources as time, money, and people’s good will eventually constrain the organization’s ability to achieve either goal (R7 and R8). In essence, the effort to achieve these goals becomes a “fix that fails” and actually erodes performance in both areas overtime.

For instance, the dangers of competing expectations and excessive workload became all too evident for a recently nationalized nonprofit organization that was trying to achieve ambitious growth goals while also learning to coordinate the work of previously independent field groups (go to http://www.pegasuscom.com/ nonprofit.html for a diagram). The problem only worsened with the reduced willingness of field and national groups to cooperate and the high turnover that resulted from increased demands on people’s time.

Tips for Tackling Conflicting Goals

How can you manage the unintended consequences that typically arise from a conflicting-goals situation? First, acknowledge that these conflicts exist. Managers often take such situations for granted and fail to grasp how powerfully they can undermine their department’s success. The above examples should leave you convinced of the pitfalls of ignoring a conflicting-goals situation.

Second, ensure that the two goals are explicit and that the consequences of trying to achieve both at the same time are understood. Third, test whether both goals should be considered equally important. You can do this by comparing the short and long-term consequences of failing to achieve each goal. For example, when Digital recognized after one year that its cost structure was not sustainable despite potential revenue gains, it took headcount reduction more seriously.

If both goals carry equal weight, consider how the organization might accomplish them through different actions or different people. For instance, the nonprofit organization cited above is giving field groups responsibility for fundraising and the national group authority for program management while strengthening coordination between the two. At the same time, maintain the pressure for task completion by rewarding people for what they achieve, not just for what they initiate.

Fourth, consider sequencing the achievement of the goals by expediting one and delaying the other. For example, reduce headcount to save costs in the short run, and then reinvest the savings in a more labor-efficient Internet business to generate additional revenues over the longer term. If the primary result of the conflict is to increase workload to levels where people burn out and leave, then you might try staggering the achievement of the goals so that the total workload at any one time is contained.

ERODING OUR ABILITY TO ACHIEVE CONFLICTING GOALS

In this case, trying to achieve two goals simultaneously (B3 and B4) undermines people’s ability to achieve either goal. The pressure of competing expectations produces side-effects that impair performance (R5 and R6). The increase in total activity may also become unsustainable as limits on such resources as time, money, and people’s goodwill eventually constrain the organization’s ability to achieve either goal (R7 and R8).

Finally, challenge the very assumption that the two goals are in conflict. By inquiring more deeply into priorities, managers often realize that some seemingly conflicting goals are in fact aligned. This phenomenon occurred when the Quality movement was introduced in the United States. Before its introduction, many managers assumed that high quality and low cost were incompatible. Over time, they learned to significantly improve quality by both increasing efficiency and reducing costs.

A similar shift in thinking is happening now in the growing alignment between environmental-quality and cost-management initiatives. Eco-efficiency projects are saving companies such as Dow and Lockheed millions of dollars, while simultaneously improving environmental quality and reducing corporate risk.

Conflicting goals are an inescapable part of organizational life. Although you can’t always prevent such dilemmas from arising, you can control how you respond to them. You can deny them or act in ways that make them worse. Or, you can develop creative approaches that will actually increase your ability to achieve what you want. With practice, you might even be able to challenge the very assumption that the conflict is inevitable!

Peter David Stroh is a founder of Innovation Associates and most recently a principal with its parent company Arthur D. Little. He is an expert in using systems thinking to facilitate organizational change and has written previously on the management of paradoxes.