The year is 1986 and the advertising industry — which prides itself on being immune to economic slowdowns — is experiencing a sharp slowdown of its own. U.S. advertising spending rose only 7.9% in 1985, less than half of the 16% increase in 1984, and many analysts predict only a 6% increase for 1986. Some ad executives are suddenly finding themselves out of work — and forced to accept 20-30% pay cuts if they land a new job. A Business Week article, citing the “unprecedented upheaval” in the advertising industry, catalogues the strategies firms are using to cope: “many agencies have attempted to keep growing by gobbling each other up. Others have opted to expand into related services, such as public relations and direct marketing. And everyone is scrambling to cut costs.”

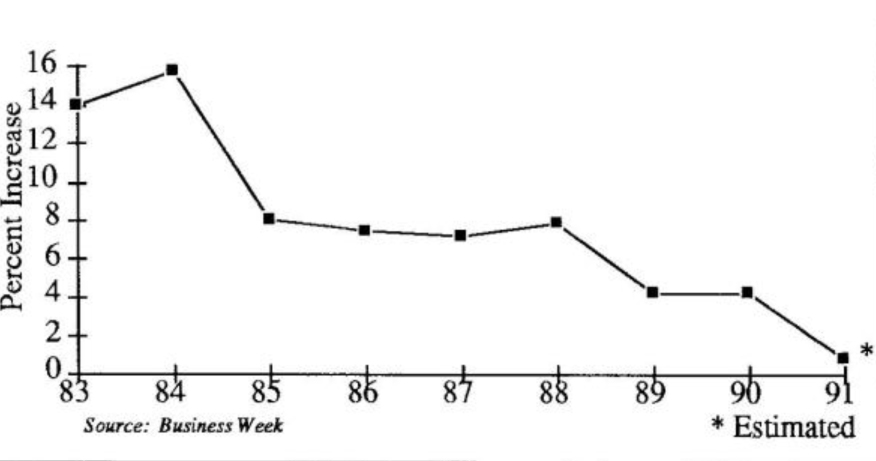

Cut to 1991…The mergers are complete: most notably, Maurice and Charles Saatchi have snapped up ad agencies in Britain and the U.S., making Saatchi & Saatchi one of the largest ad agencies in the world. Ad rums have diversified into direct marketing and promotions: Ogilvy Group Inc. and Young & Rubicam Inc., for example, are known for their “one-stop shopping” approach to clients’ advertising needs. And alternative forms of advertising are proliferating. “Today, more money is invested in direct-mail pitches, promotions and appeals than is spent on advertising in magazines or on radio or network television” notes Time magazine (November 26, 1990). But despite advertisers’ best efforts, the economic news is much worse today than in 1986 (see “Declining Growth in Ad Spending” Graph). After several years of steady or increased spending, advertising in the United States “is in the deepest and most prolonged drought in 20 years” (Business Week, September 23, 1991).

What happened?

From 1976-1988, U.S. ad spending consistently grew faster than the economy as a whole. Even during the recession of 1981-2, advertising recorded double-digit growth rates. The reason? Any slowdown in ad revenue from existing clients was offset by the introduction of new categories, such as personal computers, and the deregulation of old ones, such as airlines. But now airlines, banks, and retailers are consolidating, meaning fewer players and reduced ad spending per industry. Also, cigarette manufacturers, long a stable supplier of print ads, are relying less on advertising and more on promotions or direct marketing.

Declining Growth in Ad Spending

For advertisers, the overall slowdown in ad spending has had a direct impact on the bottom line. But so have other shifts in marketing trends. The move from high-margin media billings (newspaper, magazine, and television ads), where agencies typically receive 15% commission, to lower-margin marketing tactics such as direct marketing and promotions has hurt advertisers’ billing revenue. And as manufacturing companies look for ways to tighten their own belts, some have abandoned the 15% commission figure altogether. Kraft, Campbell Soup and Carnation, for example, now tic their agencies’ compensation to sales volume, and other companies are now negotiating for smaller commissions.

It is clear from these trends, analysts say, that advertising is entering a new age. But are the hard knocks the industry has received in the past five years simply market adjustments that will eventually return the industry to its historical growth rate? Or are they indicative of more fundamental dynamics at work?

A systemic look at the industry suggests that the current changes are fundamentally different and more lasting than previous upheavals. Old “fixes” that previously brought relief will produce diminishing returns as current advertising practices become out of sync with the needs of a changed marketplace. In order to improve their long-term performance, advertisers need to address their misplaced emphasis on growth, their reliance on short-term fixes, and a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation that may jeopardize their future effectiveness in reaching consumers with their messages.

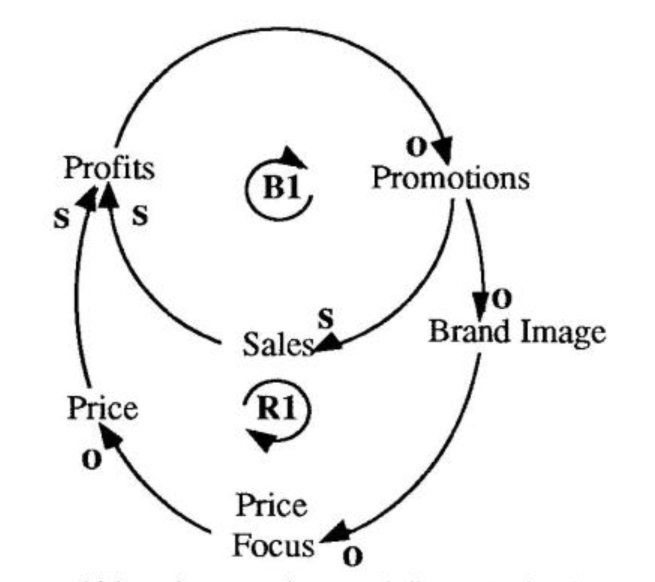

Promotions Fix

Focused on Growth

An implicit assumption underlying most companies’ strategies is that big is better, and gargantuan is heavenly. Advertisers also seem to believe that growth is the goal. “If we can’t grow internally, we’ll grow through acquisitions and mergers” is the typical mindset, as the flurry of agency mergers in the late 1980s proved. This emphasis on undifferentiated growth is consistent with a mass production mentality that centers around achieving economies of scale. As long as the organization’s inputs and outputs can be diced up and shuffled like interchangeable parts, those scale economies can be realized by merging and squeezing out redundant positions.

But as Russell Ackoff, a well-known systems thinker, points out, “Cemeteries grow, but they don’t develop.” If organizations focus on growth as the main driver, they are certain to underdeveloped their potential, since growth almost always can be achieved faster than development. In a finite environment there will always be eventual limits to growth, whereas the development of people and their capacity to create has yet to reach a limit. Leverage in the future may very well lie in developing an organization’s capacity to innovate and expand its creative potential — from which new growth may result.

Overgrazing of Consumers

Fixes that Fail

It is true that in a bad economy companies spend less on advertising, but what also happens is that they examine more closely whether they are getting the most for their advertising dollar. Recent statistics show that in many cases they are not — in 1986, according to Business Week, 64% of the people surveyed could name a TV commercial they had seen in the previous four weeks; in 1990, just 48% could. And Time magazine reports that 44% of direct mail advertising is thrown away without ever being opened. In response, companies have been moving into more promotions, coupons, and other forms of direct marketing — and advertising firms have followed their lead.

The impetus for this shift has been a short-term focus on the bottom line. As a recent Business Week article explained (“What Happened to Advertising,” September 23, 1991), “In category after category, brand managers are scrambling to boost quarterly sales instead of investing in image advertising to nurture brands for the long haul. To pump sales, they’re shifting marketing dollars from ads into promotions such as coupons, contests, or sweepstakes.”

Although the push into alternative forms of advertising has helped boost quarterly sales figures, it has also had some negative consequences which have exacerbated the 1991 downturn (see “Promotions ‘Fix'”). By organizing advertising around price focused promotions, advertisers are reinforcing consumers’ growing perception that products are commodities which are distinguished solely by price. As this perception grows, manufacturers will be increasingly forced to compete on price by offering more coupons, flashier promotions, and deeper discounts. Eventually, profit margins will be squeezed, ad budgets will shrink, and manufacturers will feel pressure to rely even more on price-focused promotions to boost short-term margins. Evidence of this shift is already apparent in the decline of brand awareness among consumers. In 1975, 77% of consumers said they buy only well-known brands. In 1990 the figure was closer to 60%.

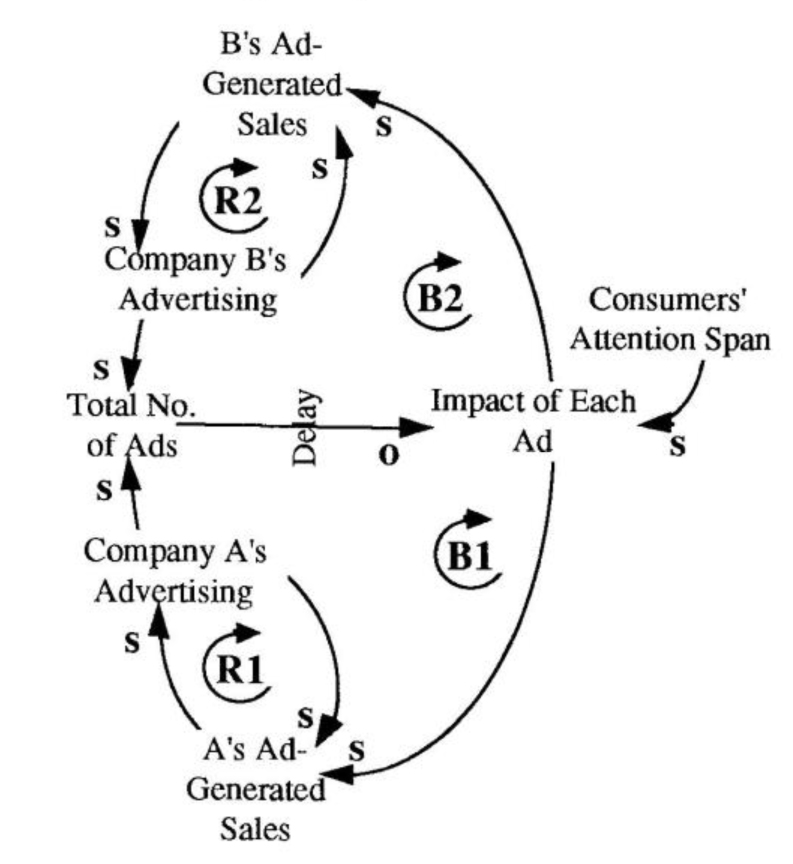

Advertising Overload

Why are promotions yielding diminished returns? Partially because of advertisers’ tremendous success in the early 1980s. One negative consequence of the huge growth in advertising over the past decade is that consumers have grown weary of the constant barrage of advertising. Many Americans, brought up on a steady diet of commercials, view advertising with cynicism or indifference. The proliferation of products and the ads promoting them have had the cumulative effect of “overgrazing” the beleaguered consumers’ attention. The same holds true with direct mail marketing, which may result in decreasing payoffs down the road as consumers grow more tired of the “junk” clogging up their mailboxes and take actions to stop it.

Voice of the Customer

In the advertisers’ version of the “Tragedy of the Commons” (see “‘Overgrazing’ of Consumers”), each company’s advertising efforts leads to more ad generated sales (R1 and R2). As every product and service gets advertised, the total number of ads increase and, over time, the impact of each ad diminishes. This has a negative effect on sales and eventually leads to reductions in advertising (BI and B2).

The lesson from the “Tragedy of the Commons” structure is ominous: advertising in the future will continue to become less effective in reaching and persuading consumers.

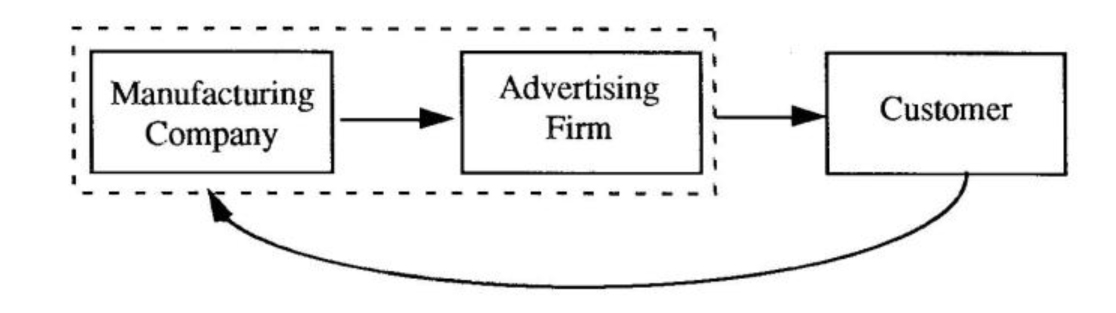

Building Relationships

In the face of such diminishing returns, what’s a company to do? The “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype tells us that consumers are growing weary of being “sold to.” This perception can lead to hostility — an “us” vs. “them” stance against the advertisers (and client companies) who clog their mailboxes, jam their airwaves, and are invading new turf such as check-out lines and elementary schools. Companies can turn this adversarial relationship around by moving away from simply “selling” their products and instead using ad agencies to devise creative ways to listen to customer needs and translate them into products and services. In order to achieve this synergy, advertising firms and their clients—manufacturing companies and service organizations — must be better aligned, not just on marketing a finished product, but in its development as well.

This alignment will translate into an important new role for advertisers — establishing enduring relationships between the consumer and the client company. This shift — from trying to sell the consumers a particular product or service to developing a relationship with the consumer — will require a different approach than traditional marketing efforts. Such a shift will require being able to identify focused customer segments with whom the company wants to do business and then establishing rapport with them.

Establishing such customer relationships mean that communication must be a two-way street. Information must flow both ways: from the customers to the company and vice versa (see “Voice of the Customer”). And it means that advertisers will need to have a much closer working relationship with their client organizations in order to be effective in a relationship-building role. A relationship that is built on trust, a history of good experiences, and frequent contact can provide customer loyalty that goes much deeper than any glitzy promotion campaign can accomplish.