Emotional Intelligence — we’ve all seen books, presentations, TV specials, interviews, and conferences about it. Even the venerable Harvard Business Review has published articles on this topic. Moreover, you can now have your “EQ” measured as scientifically as your IQ. But is Emotional Intelligence a new domain that managers should pay attention to? Or is it another “buzz du jour” that will eventually fade into just so much noise?

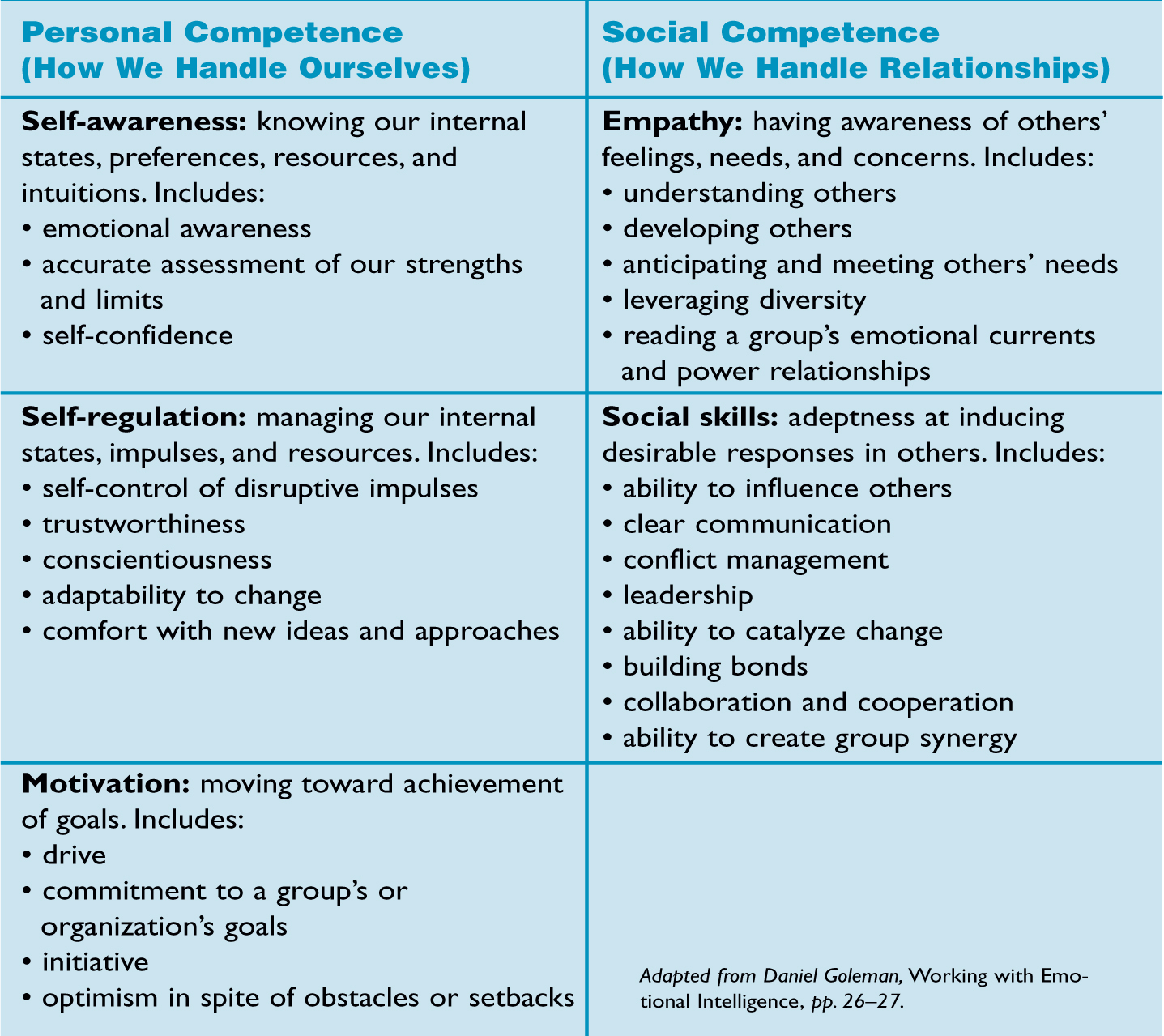

First, we need to specify exactly what we mean by Emotional Intelligence (EI). In his best-selling book Working with Emotional Intelligence (Bantam, 1998), Daniel Goleman defines it as “the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions well in ourselves and in our relationships.” Goleman goes on to define several core EI skills (see “Emotional Intelligence Skills” on p. 2).

Based on this definition, Emotional Intelligence is not a new idea. As a component of self-knowledge and of understanding others, Emotional Intelligence (the capability, not today’s movement) is as old as the inspiration of the first philosopher who exhorted followers to know themselves. It also has links to the wisdom of the earliest spiritual leader who encouraged disciples to treat one another with love and compassion. As a subject of psychological study and personal development, the examination of the inner, “nonrational” self goes back at least as far as the work of Sigmund Freud. Certainly throughout the 20th century, psychologists and organizational development theorists created models and programs to help people understand and solve their intra and interpersonal issues.

But in the 1940s, David Wechsler and R. W. Leeper began to recognize “affective intelligence” as a component of general intelligence and something distinct from intellectual or cognitive intelligence. Current Emotional Intelligence theorists cite this work as the starting point for today’s EI movement. Other researchers, including Peter Salovey, Jack Mayer, and Reuven Bar-On, contributed additional work to define this emerging field in the 1980s and 1990s.

Building on this earlier research, Daniel Goleman’s books Emotional Intelligence (Bantam, 1995) and Working with Emotional Intelligence dramatically opened up the idea of EI to people around the world by bringing the earlier research to the public’s attention in an accessible way. The field took. off, and more than 200 books on the topic have been written in the past two years alone.

“Smart” People, “Stupid” Mistakes

One reason for this surge of attention is captured in Goleman’s own words: “The rules of work are changing. We are being judged by a new yardstick: not just by how smart we are, or by our training and expertise, but also by how well we handle ourselves and each other” (Working with Emotional Intelligence, 1998, p. 3). Why this shift in work rules? As competition and globalization intensify, as technology grows more complex, and as the imbalance between work and family/community life spins further out of control, companies everywhere are realizing that cognitive IQ simply isn’t enough to run productive, thriving organizations.

Similarly, studies are beginning to document that not managing our own emotions can actually interfere with our cognitive intelligence. Specifically, when we let ourselves get overwhelmed and stressed, our thinking becomes impaired. We then say and do things that can damage our own health and livelihood, our relationships with our coworkers, and ultimately our organization’s bottom line.

To explore the benefits of helping employees learn new ways to handle tension and conflict, Motorola contracted HeartMath LLC, a consulting firm in Boulder Creek, CA, to conduct a six-month productivity study to see if focusing on emotional management techniques would benefit productivity, teamwork, communication, and health. The results showed that 26 percent of trainees saw their blood pressure drop, 36 percent reported reduction in stress symptoms, and 32 percent claimed increased feelings of contentment. Fifty-seven percent said that their productivity improved by more than 50 percent, 47 percent reported a 50-percent improvement in teamwork, and measured quality rose by 22 percent (, “Self-improvement, Corporate Style” by T. Kinni, Training, May 2000). Clearly, emotions can be a vital resource if organizations fully leverage them.

Emotional Intelligence has also surfaced as an issue for organizations struggling to understand why “smart” people sometimes make “stupid” mistakes. For example, Fortune’s June 21, 1999 feature article, “Why CEOs Fail,” pointed out that leaders rarely strike out because of lack of smarts or vision. Authors Charan and Colvin contended that “Most unsuccessful CEOs stumble because of one simple, fatal shortcoming . . . the failure is one of emotional strength.”

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE SKILLS

Linking Head and Heart

The fact remains that having a high IQ (in the traditional sense) is not enough to be effective in the workplace. The good news is that, with training and practice, EI can be learned. EI is about having “street smarts” in addition to cognitive smarts, about the head and heart working together. Emotional Intelligence comprises three components: (1) an awareness of our own emotional state and its impact on ourselves and others, (2) an awareness of others’ emotional states, and (3) the ability to manage and make use of that awareness. These skills play a central role in at least three aspects of organizational effectiveness — in particular, personal development, collaborative learning, and systems thinking.

Personal Development. Effective organizations are built on a foundation of effective individuals. As Tellabs manager Debbie Reichenbach explains, “If people feel personally balanced, they are able to make more effective decisions, and we can leverage their personal effectiveness. We have a highly intelligent workforce, and we have to maximize the use of that” (Training, May 2000). But how can we become more productive in the workplace? One way is by increasing our capacity to learn from experience and to gain insight into the personal motivations, choices, beliefs, and thought processes that motivate our behavior.

Cultivating these abilities takes practice. In HeartMath’s programs, participants learn activities that help them manage stress and balance the mind and the emotions with the body. In the Freeze Frame® exercise, for example, individuals shift their attention away from a problem that is causing stress and instead focus on positive feelings in the area of the heart. This one-minute drill brings respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure into synchronization. It also allows the individual to gain perspective and bring clearer thinking to the situation.

Collaborative Learning. For both constructive reasons (strengthening the capacity for team learning) and preventive reasons (avoiding interpersonal problems), EI plays a key part in effective teamwork. Well-rounded self-awareness—among team leaders and members alike — is essential for both successful work projects and a thriving company culture. Specifically, individuals who lack awareness of their own inner drives and feelings also have trouble sensing their impact on others. For example, a “micromanager” who doesn’t recognize her own need for control also won’t perceive the extent to which she saps subordinates’ sense of independence. And a bully usually ignores his own feelings of vulnerability as well as the humiliation or anger he generates in his colleagues. Few teams can thrive under these sorts of conditions.

Through exploring and developing their EI, team members can improve their ability to contribute to projects and build productive work relationships. EI skills let individuals better understand each other and communicate more effectively about what is important to them. For example, a key manager at Intel recently described how, when members of far flung global teams spent time learning about each other’s interests, hobbies, and families, their ability to collaborate at a distance by e-mail improved noticeably. Why? Because they knew each another as three-dimensional, distinct individuals, and their personal and emotional connections were more complete.

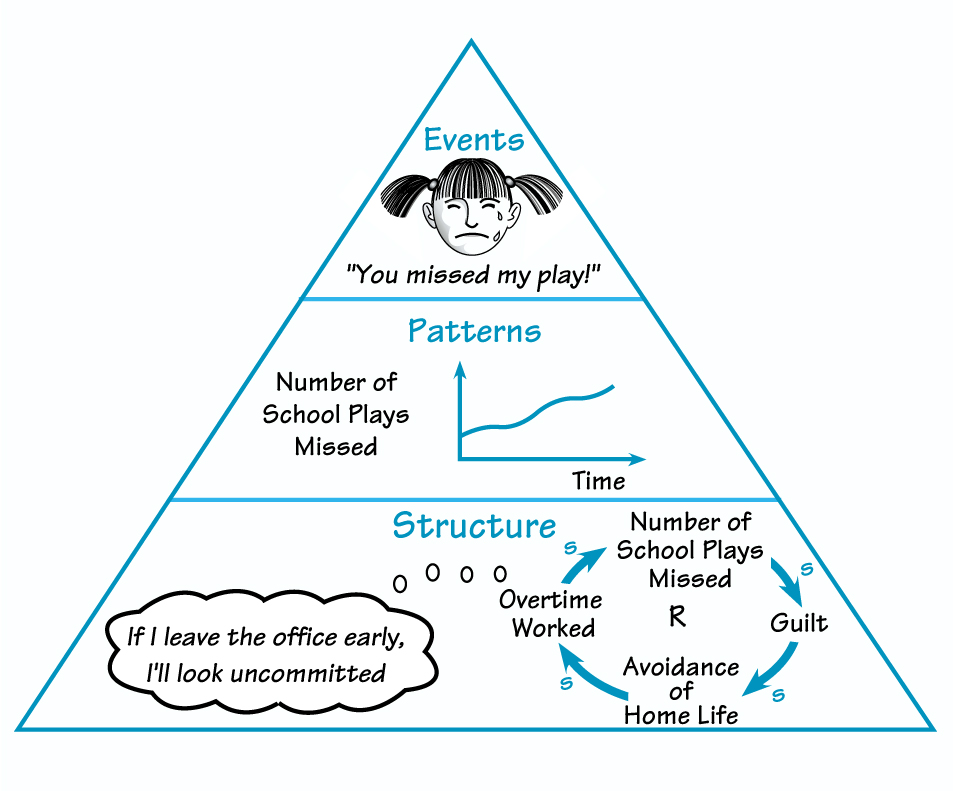

Systems Thinking. To us, systems thinking is a third key element of personal and organizational effectiveness. A classic way of introducing people to thinking systemically is to use the events/patterns/structure “iceberg” model. This framework teaches us that systemic structures — which can include feelings, beliefs, and motivations — give rise to patterns of behavior and, ultimately, the events that we observe.

For instance, suppose you miss your daughter’s school play this week (an event) (see “Missing the School Play — Again”). You apologize, really believing that this is a unique occurrence. But she points out that you have missed six school events this year (a pattern). When you delve deeper, you might discover that your underlying assumptions and emotions are contributing to this pattern of behavior (a structure). For example, you might be under intense pressure to meet work deadlines, and you might be fearful of being perceived as uncommitted or incompetent by your colleagues if you leave the office early.

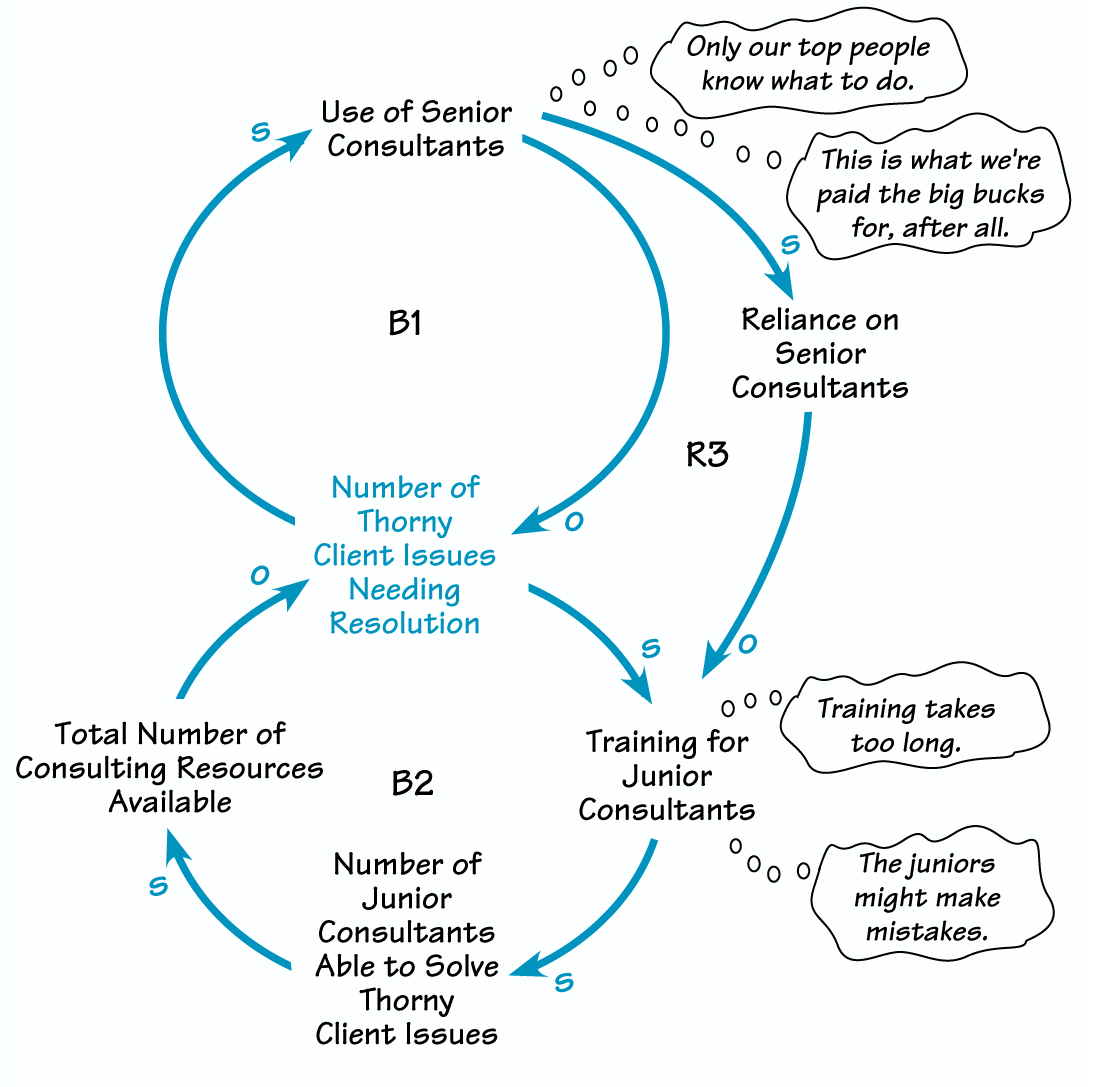

This model suggests that, like the submerged portion of an iceberg, systemic structure is difficult to see and much more substantive than we might expect. Drawing causal loop diagrams (CLDs) with others can help us to clarify our understanding of those structures. As management consultant Rick Karash explains, we can deepen our understanding of the systemic structures we’ve depicted in a CLD by asking what feelings and assumptions motivate people to make the choices represented in the diagram.

For example, in “Shifting the Burden to Senior Consultants” on p. 4, fears of not satisfying clients force ConsultSmart to turn to its senior consulting staff to solve thorny client issues (B1). As a result, the company comes to rely too heavily on its senior staff and invests less in training for junior consultants (R3). This decision ultimately constricts the total resources that ConsultSmart has available to offer clients (B2).

In diagramming a system, the clearer and more complete your picture of the deepest levels of structure, the more powerful and useful the insights you and your team can gain from the diagramming process. Because Emotional Intelligence enhances understanding of one another’s feelings, relationships, and motivations, it is a critical competency for understanding organizational systems.

Emotional Intelligence in Action

Behavioral change programs have been around for many years. The challenge facing EI practitioners today is how to design new training modules based on developing this aspect of intelligence. The theorists have done their job of bringing these concepts into our awareness; now it is up to the practitioners to diffuse effective EI programs into the corporate world.

Practitioners are finding business applications for this work in numerous areas, including executive coaching, employee selection and retention, team building, and leadership development. The number of companies that are developing EI programs is growing. Some of them are building their own programs from scratch; others are revising their standard materials to incorporate EI. Below are just a few examples:

American Express Financial Advisors (AEFA). The first successful EI program, the Emotional Competence Program, was developed at AEFA in 1992 by a team lead by Kate Cannon, Director of Leadership Development. The philosophy supporting the program is that, if individuals can identify their motivations and emotional states, they will communicate more effectively with colleagues, establish stronger relationships, and achieve their personal and professional

MISSING THE SCHOOL PLAY—AGAIN

goals. According to Cannon, the program was developed to help leaders carry the company into the future. “So much had changed, we needed leaders who could support the business — leaders who were flexible and adaptable, who could develop relationships” (Workforce, July 1, 1999).

Initially, the company found that 60 financial planners who participated in the pilot program outperformed their associates. A more recent evaluation suggests that participation in the program has continued to boost sales revenue. In that study, sales in regions where the managers attended the program increased 11 percent more than in regions where managers did not attend the workshop. The financial planners said that participating in the program was the number-one factor in their success.

In a third study, the Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) — an assessment tool that measures people’s ability to handle day-to-day pressures and demands and achieve successes — was administered as a pre- and post- test for the AEFA group. The EQ-i results revealed that participants’ scores improved on most of the tool’s 15 subscales. AEFA’s training and testing program was the first objectively evaluated instance that demonstrated that EI can improve as a result of a learning program.

Nichols Aluminum. The Emotional Competence Program proved so successful that American Express has made it available to other companies interested in building EI competencies. One of those companies is Quanex Corporation’s Nichols Aluminum Division, a scrap-based aluminum sheet manufacturer with 750 employees at five plants in Iowa, Illinois, Alabama, and Colorado.

Coming off a record fiscal year in 1999 with sales increasing 17 percent to $312 million, Nichols wanted to find innovative ways to support and sustain its success. Terry Schroeder, who had become president in 1996, decided that the company needed to cultivate a culture that empowered employees to make smarter decisions. Training manager Jan Daker had read an article about AEFA’s Emotional Competence Program and recognized its potential.

Nichols brought the AEFA program in initially to strengthen communication and trust among senior managers. One program participant disclosed, “The Nichols culture had been very stilted and withdrawn.

SHIFTING THE BURDEN TO SENIOR CONSULTANTS

No one knew how to express their emotions constructively, and we needed emotional competence to build the business.” A core group of 20 such individuals took the four-day program in July 1999. The EQ-i was given as a pre-test to benchmark EI, then administered again at the end of the program. A consultant gave individual feedback to all participants to help them understand their strengths and areas for development. He visits Nichols every three to four months to do follow-up coaching with the original participants.

Evidence indicates some promising results from the program. In describing the impact of EI on teamwork, an employee described a colleague who had completed the training in this way: “He is much more in control of his emotions now, less vulnerable, less frustrated, and less angry. He is more people oriented, listens, asks for my input, and asks for the urgency level in order to judge the response time needed from him.” In addition, the senior group is more united as a team, and communication throughout the plants has improved.

In one plant near Chicago, only four people attended the training — yet their experience has rippled outward to the remaining 130 employees at that location. Like other Nichols facilities, since the program took place, the Chicago site has repeatedly reached new levels of operational and financial performance, with higher volumes, sales, and profitability. Daker is delighted with the results. In her view, the training has given employees more access to high-level managers, and has let them make new connections that have positively influenced the entire organization. A second program was offered in the summer of 2000.

The Future of EI

The need for Emotional Intelligence has been around since primates began to live in groups. Over the centuries, recognition of the need for these abilities has periodically risen and fallen in many cultures, depending on larger societal trends. For instance, the emotionally centered Romantic Movement, a literary and artistic outlook that emerged in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, sprang up in opposition to the Age of Reason and to industrialization. Romantics decried what they saw as cold-minded, mechanistic thinking. Scientists and industrialists in turn scoffed at the artists’ so-called mushy and fuzzy-brained thinking.

Similar skepticism by business-people about how to apply EI theories in the workplace is understandable. Though many activities in the human-potential movement do generate insights in the moment, it has been harder to demonstrate that they consistently produce long-lasting and self-sustaining results. Moreover, there is a history of faddish adoption and then rejection of new ideas, techniques, or vocabularies in the organizational arena. In some cases, the concepts have not been founded on well thought out and tested principles. In other cases, people become infatuated with a trend because it resonates with a deep societal need or a widely held feeling.

But like many new lovers, the proponents of the latest craze are not as clear-eyed as they might be about their beloved. Often, they believe it to be capable of more than it really is. In certain instances, a new idea or technique may actually have substance, but too many “quick fixers” promote it without taking the time and discipline required to acquire the skill, wisdom, and true benefits that the work offers. Six months later, the idea “didn’t work,” and its ardent proponents are off pursuing something else. Onlookers become cynical, quick to condemn the next new discovery as “just another fad.”

PRACTICING EI WITH YOUR TEAM

- Create shared guidelines and expectations for respectful listening and speaking during meetings. Example: No interrupting.

- Maintain the habit of inquiring into each other’s thoughts, motivations, and emotions related to key ideas or decisions. Example: “What made you think that this idea was valuable?” or “What is your feeling in this moment about this situation?”

- Practice respectfully disclosing “left-hand columns” — those thoughts and feelings you typically keep to yourself. Example: “You know, I have to confess that I’m not following you.”

- Accept one another’s point of view, experiences, and needs as real. Example: If you acknowledge that the finance manager is under a lot of pressure to cut costs, you might better be able to understand her desire to reduce your department’s budget.

- Imagine six or more alternative explanations for another person’s behavior instead of limiting yourself to just the first interpretation that comes to mind. Example: “Hmmm . . . he seems angry at me. But maybe he had a rough commute, or had a disagreement at home this morning, or . . .” and so on.

As a field, EI could ultimately meet the same fate that other worthy ideas have encountered — if practitioners allow it to lose credibility. They must not present it as a panacea when it is just one among several valid frameworks for improving personal and organizational effectiveness. Practitioners should also avoid creating excessive “pie in the sky” expectations. Enhancing Emotional Intelligence requires hard work and persistence; there’s no “quick fix.”

Even the success stories about organizations that have implemented EI awareness or competency programs are still too new to allow any of us to make confident declarations of EI’s undeniable validity. However, we believe that EI has enormous potential to play a fundamental part in building long-term personal and organizational health. Certainly it takes intense effort and patience — but so does anything that has real value. Only time, inquiry, evaluation, and adaptation in light of new knowledge — in short, organizational learning — will prove the lasting power of EI.

Debra Duxbury (debdux@aol.com) is an independent consultant with 20 years’ experience delivering innovative training programs to industry. She is certified in and trains others to use and apply the EQ-i assessment in training programs. Prinny (Virginia) Anderson (vranderson@aol.com) is an independent organizational learning consultant, coauthor of Systems Thinking Basics: From Concepts to Causal Loops and Systems Archetype Basics: From Story to Structure, and certified in the use of the EQ-i tool as well as tools for corporate cultural values assessment.

Further Reading Bar-On, R. EQ-i, Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory, Technical Manual. Multi-Health Systems, Inc., 1997.

Cherniss, C. Beyond Burnout. Routledge, 1995.

Childre, D., & B. Cryer. The HeartMath Solution. Harper, 1998.

NEXT STEPS

- With a team, map out how fostering Emotional Intelligence in the workplace might affect the company’s bottom line in the areas of leadership, retention, career development, and health. Then, begin to develop skills by following the tips in “Practicing EI with Your Team.”

- In a group, refer to the table “Emotional Intelligence Skills” on p. 2 and determine which EI competencies are strategic priorities for your business. Then rank your organization or department on the level of skills that employees as a whole demonstrate in each of these areas. For problem areas, analyze how organizational structures or policies may be limiting workers’ EI.

- List your present roles and responsibilities. How could expanded EI improve your functioning on a project or in working with a colleague? Identify your priorities for developing your own EI and develop an action plan.

- Think about your best and worse bosses. What positive and negative attributes did they have that had a powerful impact on you? Categorize each of those qualities as intellectual or emotional characteristics.