Every partnership occasionally runs into rocky roads, but the relationship between U.S. auto giant Ford Motor Company and Japanese tire maker Bridgestone/Firestone Inc.recently hit a massive pothole. In August, Bridgestone issued a recall in response to reports that tread separation on tires on some Ford vehicles had caused more than 750 accidents and at least 88 deaths in the U.S. alone. The companies’ failure to address reports of problems sooner led to federal investigations.

Instead of banding together in the face of this scrutiny, Ford and Bridgestone/Firestone have publicly traded accusations. In the most recent round of barbs, Ford executives laid all of the blame on faulty tires, while Bridgestone/Firestone officials alleged that drivers under inflated their tires based on Ford’s recommendations and that design flaws make the Ford Explorers susceptible to rollovers. The result of this escalating war of words has been negative publicity for both companies, as well as costly litigation.

Covering Your Assets

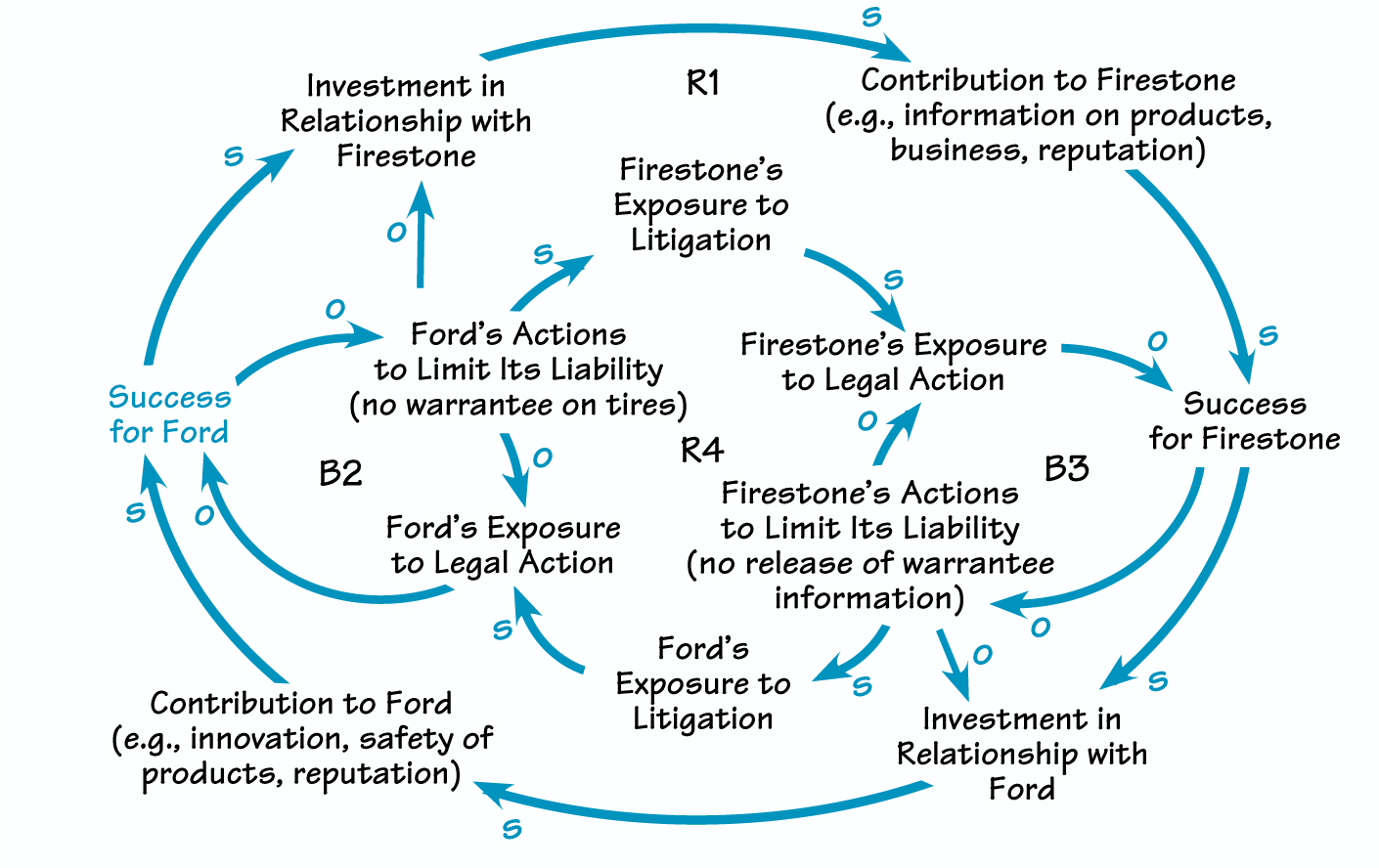

How did this once productive partnership turn sour? We might view the current crisis as a variation of the, “Accidental Adversaries” structure (see, “Wobbling to Success by Managing the ‘Accidental Adversaries’ Dynamic” in V11N9). When things were going smoothly, the association between the two brands led to success for both parties (R1 in “A Demolition Derby?”). Firestone’s public image as the maker of safe and reliable tires enhanced Ford’s image and vice versa.

A DEMOLITION DERBY?

When things were going smoothly, the association between Ford and Firestone led to success for both parties (R1). But the underlying dynamics caused each firm to take actions that undermined the partnership (B2) and (B3). When problems arose, the only solution seemed to be to blame the other (R4)

But the underlying dynamics between car companies and tire manufacturers caused each firm to take actions that subtly undermined their partnership and perhaps even their customers’ safety. Tires are the only significant part of a new car that the automaker doesn’t warrantee. In this way, they avoid responsibility for tire failures(B2). In turn, tire companies protect their position with auto makers by not sharing information about warrantee claims (B3).

This “cover-your-assets” behavior means that the companies can easily overlook patterns of problems. It also interferes with joint problem solving once difficulties do come to light. At that point, the only solution seems to be to cast the blame elsewhere (R4).

Avoiding the Scrap Heap

How can applying the “Accidental Adversaries” structure help in this situation? One leverage point is realizing that the way the relationship between tire makers and car companies is structured impedes the flow of information and almost guarantees that the parties will act based only on their own self-interest. Partners need to highlight the benefits of mutual success and the dangers of mutual failure and find ways to enhance that success. Doing so involves communicating about potential problems early in the process and seeking joint solutions. Otherwise, they may end up in a destructive demolition derby with both parties destined for the scrap heap.