Video renters visiting their local Blockbuster Video outlet have noticed something over the past year or two: They don’t have as much trouble getting a copy of a new release as they used to. The reason is something called revenue sharing. Revenue sharing allows Blockbuster outlets to put many more copies of each new release on the shelves than ever before, and gives them the opportunity to advertise “guaranteed availability.” That’s good news for Blockbuster and for consumers, but others in the industry are up in arms over the issue. And although this innovative strategy may prove lucrative for Blockbuster in the short run, according to an article in Variety (“‘Ryan’s’ Trench War” by Paul Sweeting, May 31-June 6, 1999), it may ultimately play a part in hastening massive consolidation in the video-rental industry and the demise of the video store as we know it.

Responses to Declining Profits

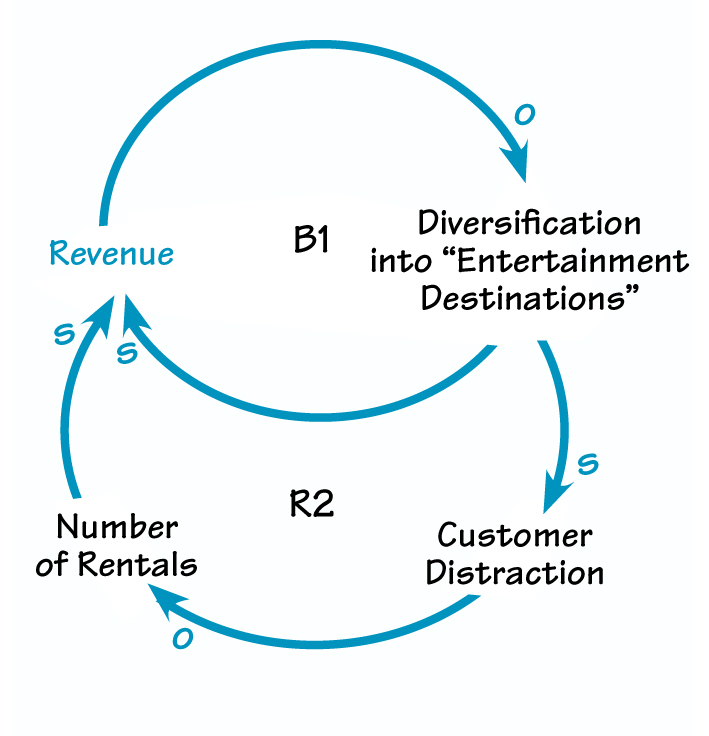

In 1996, after many years of booming growth, the market for video rentals seemed to reach a plateau. Retail giant Blockbuster Video was losing market share to competitive national chains and local video stores. Many speculated that the video-rental business itself was in permanent decline owing to the increasing popularity of secondary media such as pay-per-view. New CEO Bill Fields, hired away from WalMart to revitalize the company, tackled the challenge head-on. Under his leadership, Blockbuster outlets were transformed from mere video-rental stores into what he called “Entertainment Destinations,” featuring CDs, toys, games, snacks, books, and other attractive movie-related merchandise (see B1 in “Entertainment Distractions”).

ENTERTAINMENT DISTRACTIONS

Unfortunately, this strategy proved to be a “Fixes That Fail.” According to Blockbuster’s in-store research, these other items actually distracted customers from the company’s core business. Video rentals plummeted even further, and the smaller margins on the other merchandise did not come close to making up for the loss of revenue from tape rentals (R2).

A little more than a year into the job, Fields resigned and was replaced by former Taco Bell head John Antioco, who initiated a massive customer research effort. What he found was that Blockbuster customers were frustrated by one thing above all: lack of availability. When they couldn’t get a copy of a new release at Blockbuster, they would look elsewhere. Eventually, viewers began to turn to other sources first. They saw no advantage in going to Blockbuster over going to the local “mom and pop” video-rental outlets.

<h2

Acting quickly, Antioco removed many of the distracting elements from the Blockbuster outlets and began to focus the company on its core business once again. He also went to the movie studios and engineered a new deal called revenue sharing: Blockbuster would buy many more copies of each release than before, at a reduced rate, and in turn would share half the rental revenue with the studios. The studios, already making an average of 30 percent more from tape rentals of a title than from its original U.S. theatrical release, eagerly signed multiyear contracts, more than making up in volume what they would lose in per-tape income.

Questions for Reflection

- What might have been some of the causes contributing to Blockbuster’s loss of market share in the mid-1990s?

- What other fixes besides diversification might they have tried, and what might the consequences have been?

- Do you think the background of the two CEOs had an impact on the strategies they chose to pursue? Could there have been approaches to the problem better suited to the unique challenges of the video-rental industry?

- Are there possible parallels between Blockbuster in the mid-1990s and any other businesses today?

- What might be some unanticipated consequences of Blockbuster’s deal with the movie industry for the video-rental business as a whole?

Consequences, Intended and Otherwise

Revenue sharing seemed to promise to create a virtuous cycle that would increase the success of everyone involved in the video-rental business. Unfortunately, other factors served to limit that success, and the very survival of some of the smaller players is now in jeopardy.

Before we continue the story, let’s take a closer look at the movie industry. A studio first releases a title to theaters through distributors, collecting revenue by charging rental fees for the film (often tied to ticket sales). When revenue from the theatrical release declines, the studio puts the title on tape and sells copies to video-rental outlets -the major chains, such as Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, and thousands of independent video stores. At the same time, the studio makes the tape available for sale to the public through retailers. As rental demand for a video tapers off, the video stores sell the used copies at low prices. Soon thereafter, and sometimes concurrently, the studio releases the movie on pay-per-view. As soon as a movie becomes available on pay-per-view, tape rentals decrease even further, as many viewers choose to take advantage of the in-home alternative to a trip to the video store.

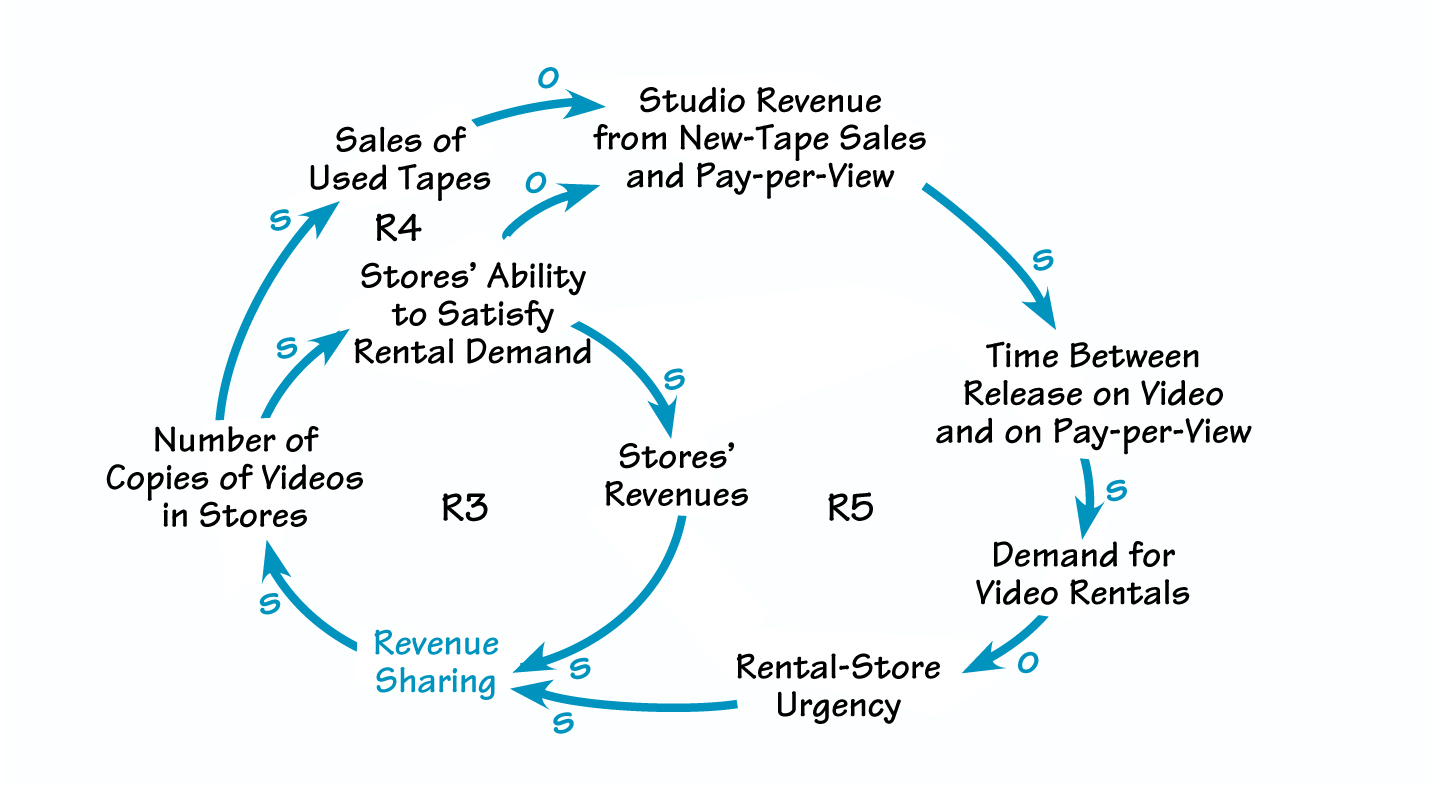

The implementation of revenue sharing greatly increased the number of copies of each new release in participating stores (see R3 in “Good Intentions”). To maximize their investment in inventory, the stores had to sell the used videos before the title became available on pay-per-view. But with so many used-tape sales, demand for new tapes and for pay-per-view dropped. Wanting to avoid a dip in this source of revenue, the studios reacted by reducing the time between releasing a video for rental and offering it on pay-per-view (“the window”) (R4 and R5). With a shorter window, video stores needed to collect their rental income more quickly. They began to order even more copies of new releases, so as not to lose a single customer owing to lack of availability. This strategy succeeded all too well – rental demand was satisfied faster, which led the studios to shorten the window even more.

GOOD INTENTIONS

Revenue sharing unintentionally set in motion a series of powerful reinforcing loops. Participating stores increased the number of copies of each new release that they ordered, reducing the time-frame for satisfying the rental demand (R3). To maximize their investment in inventory, the stores had to sell the used videos before the title became available on pay-per-view. Wanting to make up revenue lost in new-tape and pay-per-view sales, the studios reduced the time between releasing a video for rental and offering it on pay-per-view (R4 and R5). This action increased the stores’ sense of urgency and the number of copies of videos that they ordered.

Further complicating the issue is the fact that the studios do not offer revenue sharing to all outlets. The two major chains, Blockbuster and Hollywood Video, move much higher volumes of tapes and can afford to gain slimmer margins than can smaller outlets. In addition, through a single contract with Blockbuster, a studio forges an agreement with many stores; managing individual revenue sharing contracts with a number of independent store owners would represent a great deal of effort for relatively little return. Consequently, the smaller outlets can’t promise “guaranteed availability” and must pay up to 10 times as much per tape as the major chains. They can’t sell used tapes as profitably as the Blockbuster outlet down the street can — and the Blockbuster outlet has many more copies available for sale.

Because of their participation in revenue sharing, Blockbuster and Hollywood received over 60 percent of the tapes shipped for Saving Private Ryan, although their combined market share was only around 40 percent. Thus, economies of scale and revenue sharing give the major chains an advantage that is likely to grow over time — a classic “Success to the Successful” scenario. As smaller outlets go out of business at an alarming pace, the large chains continue to gain market share — a consolidation in the business that lets them grow even as the industry as a whole struggles with the dynamics launched by revenue sharing.

Will Blockbuster Reign Supreme?

On the surface level, there would seem to be little standing in the way of success for the video-rental giants. However, as we know, any business is a part of a larger system. In this case, the most serious challenge to Blockbuster and its fellow behemoths may not come from within the industry at all.

If there has been one factor rattling the cages of business owners in the late 1990s, it has been the Internet. Tried-and-true business models have become obsolete overnight, and long-time standards have been replaced by rules that change so quickly that even those with the resources to play by the new rules are finding it difficult to keep up. Television talk-show hosts now routinely refer to how many copies of a guest’s book have been sold on Amazon.com, rather than its position on the New York Times bestseller list. Could the Internet fundamentally change the video-rental industry as well?

One of the promises that the Internet holds for film producers is something known as video on demand (VOD). This up-and-coming technology will enable a distributor to send a movie to a requestor over the Internet. There would be no need for physical tapes, and so no customer would ever be turned away because all of the copies had been rented. Additionally, distributors wouldn’t incur the costs associated with manufacturing and shipping tapes. VOD would ultimately render all video stores obsolete.

Tried-and-true business models have become obsolete overnight, and long-time standards have been replaced by rules that change so quickly that even those with the resources to play by the new rules are finding it difficult to keep up.

There are obstacles to this method of distribution. For example, most experts believe that the technology to make VOD viable is still several years in the future. Also, no one yet knows whether customers will be willing to watch movies on a computer screen, if that proves necessary. Nevertheless, many players are currently scrambling for position in what could become the video-rental game of the future. Trimark, a distributor, has formed a subsidiary known as CinemaNow, which has gone online with a preliminary Web site. CinemaNow will provide Trimark’s entire library of movies over the Internet, offering free and pay-per-view options combined with advertising and an online store for movie-related merchandise. A new player, AOL Time Warner, combines a high-bandwidth cable network with access to 20 percent of total U. S. households, an Internet portal with 20 million subscribers, and the entire Warner Brothers studio’s movie library.

In an interesting twist, Amazon.com already allows customers to place advance orders for tapes of new releases before they become available. This allows a customer who is impressed by a preview for an upcoming movie to order the tape even before the movie is released. Instead of standing in line to buy a fistful of tickets for the whole family to see the movie in the theater, the purchaser can merely wait for the tape to arrive.

Gauging the Systemic Impact

Although it’s too early to predict what will come of these possibilities, it’s clear that the growth of different kinds of secondary media will continue to squeeze even the major players in the video-rental business. Thus, while Blockbuster is currently enjoying its comfortable seat within a “Success to the Successful” dynamic, they may face a bumpy ride on a “Limits to Success” archetypal structure lurking just around the corner. For, what good is having the overwhelming share of a market, if that market shrinks out of existence? Just as Blockbuster changed the game rules of the video-rental industry when they introduced revenue sharing, others may develop even newer strategies and technologies – and this time, it will be Blockbuster’s turn to react to this changing reality. Whether the company succeeds may well depend on their ability to gauge the impact of their own actions on the larger system in which they operate.

NEXT STEPS

- The Blockbuster story depicts the dangers of unintended consequences. Even when a strategy is successful — like the company’s use of revenue sharing to reclaim market dominance – a less obvious aspect of that dynamic may undermine the strategy over the longer term — like the studios’ reducing the time before releasing videos on pay-per-view. Identify several initiatives that your department or organization has undertaken that seem successful. Can you find hints that certain unintended consequences of these strategies may ultimately undermine their success? You may want to use causal loop or stock and diagrams to help identify causal relationships, delays, and long-term outcomes

- List several key aspects of your job, department, or organization and graph the impact that new technologies have had on those variables over the course of the past year or two. For instance, how has the Internet affected your customer base over the past few years – do you have more, fewer, or the same number of customers than before? What patterns have your key competitors experienced? How do you think the actions that you and your competitors take over the next five years will affect these trends? Even if your organization has a well-formed strategic plan for dealing with changing industry conditions, taking the time to graph your assumptions over time can help you identify potential weaknesses, oversights, and contradictions in your action plans.

Richard White is a writer, performer, and director. He is currently the chief specialist in organizational design, learning, and process at the consulting firm Approach Inc.