It’s another busy night in the hospital emergency room. Several car accident victims have been rushed into surgery, one little boy is having a broken arm set, a drug overdose victim is being treated, and numerous other people fill the chairs in the waiting room. Each night is different, and yet they are all the same. The doctors and nurses must act fast to treat the most seriously injured, while the others wait their tum. Like an assembly line of defective parts, patients are diagnosed, treated and then released. Each injury is a crisis that demands immediate attention.

So what’s wrong with this picture? After all, isn’t this what emergency rooms are meant to do? The answer depends on the level of understanding at which we are looking at the situation.

Levels of Understanding

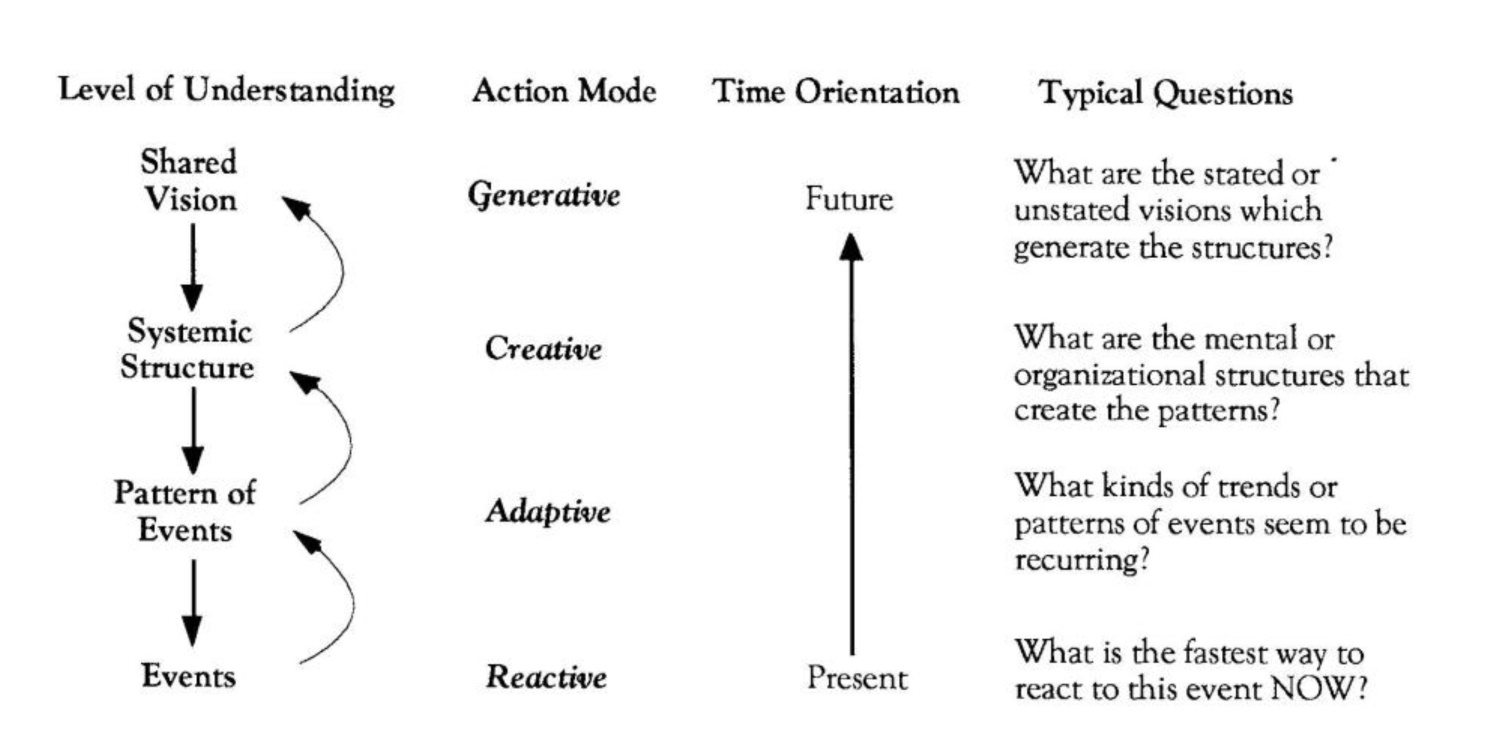

There are multiple levels from which we can view and understand the world. From a systemic perspective, we are interested in four distinct levels — events, patterns of events, systemic structure, and shared vision (see “Levels of Understanding”). Events are the things we encounter on a day-to-day basis: a machine breaks, it rains, we eat dinner, see a movie, or write a report. Patterns of events are the accumulated memories of events — when strung together as a series over time, they can reveal recurring patterns. Systemic structure can be viewed as “event generators” because they are responsible for producing the events. Similarly, shared vision can be viewed as “systemic structure generators” because they are the guiding force behind the creation or change of all kinds of structures.

We live in an event-oriented world, and our language is rooted at the level of events. At work, we encounter a series of events, which often appear in the form of problems that we must “solve.” Our solutions, however, may be short-lived and the symptoms can eventually return as seemingly new problems (see “Using Fixes that Fail to Get off the Problem-Solving Treadmill,” Vol. 3, No. 7, September 1992). This is consistent with our evolutionary history, which was geared toward responding to immediate events — those things that pose an immediate danger to our well-being.

Levels of Understanding

Events require an immediate response. If a house is burning, we react by taking action to put out the fire. Putting the fire out is an appropriate action, but if it is the only action that is ever taken, it is inadequate from a systemic perspective. Why? Because it has solved the immediate problem (the burning house), but it has done nothing to alter the fundamental structure that caused that event (e.g., inadequate building codes, lack of fire detectors, fire prevention education). The “Levels of Understanding” diagram and framework can help us go beyond typical event-orientation responses and begin to look for higher-leverage actions.

From fire-fighting to Fire Prevention

At the event level, if a house is on fire, all we can do is react as quickly as possible to put the fire out. The only mode of action that is appropriate and available is to be reactive. If we reacted to fires only at the events level, we would put all of our energy into fighting fires — and we would probably have a lot more fire stations than we do today.

As fire-fighters, if we look at the problem of fires at the pattern of events level, we can begin to anticipate where fires are more likely to occur. We may notice that certain neighborhoods seem to have more fires than others. We are able to be adaptive by locating more fire stations in those areas, and staffing them accordingly (based on past patterns of usage). Because the stations are a lot closer, we can be more effective at putting out fires by getting to them sooner. Being adaptive allows us to be more effective fire-fighters, but it does nothing to reduce the actual occurrence of fires.

At the systemic structure level we begin asking questions like: “Are smoke detectors being used? What kinds of building materials are less flammable? What safety features reduce fatalities?” Actions taken at this level can actually reduce the number and severity of fires. Establishing fire codes with requirements such as automatic sprinkler systems, fire-proof materials, fire walls, and fire alarm systems, saves lives by preventing or containing fires. Actions taken at this level are creative because they help create a different future. Systemic structure includes not only the organizational structures and physical buildings but people’s mental models and habits as well.

Where do the systemic structures come from? They are usually a reflection of a shared vision of what is valued or desired. In the case of fire-fighting, the new structures (e.g., fire codes) were born out of a shared value of the importance of protecting human lives, and of living and working in buildings that would be safe from fires. At the level of shared vision, our actions can be generative, to bring something into being that did not exist before. At the level of shared vision, we begin asking questions like “What’s the role of the fire-fighting function in this community? What are the trade-offs we’re willing to make as a community between the resources devoted to fire-fighting compared to other things?”

It is important to remember that the process of gaining deeper understanding is not a linear one (from events to shared vision). Our understanding of a situation at one level can feed back and inform our awareness at another level. Events and patterns of events, for example, can cause us to change systemic structures and can also challenge our shared vision. To be most effective, the full range of levels must be considered simultaneously. The danger lies in operating at any one level to the exclusion of the others.

Our ability to influence the future does, however, increase as we move from the level of events to shared vision. Does this mean that high-leverage actions can only be found at the higher levels? No, because leverage is a relative concept, not an absolute. When someone is bleeding, the highest leverage action at that moment is to stop the bleeding. Any other action would be inappropriate. As we move up the levels from events to shared vision, the focus moves from being present-oriented to being future-oriented. Consequently, the actions we take at the higher levels have more impact on future outcomes, not present events.

Back at the Emergency Room

The emergency room (ER) offers a very graphic example of a situation in which people must be focused on the present. It also reveals the limitations, however, of the events-oriented response. ER treatment offers maximal leverage to affect the present situation with each patient, but it provides very little leverage for changing the future. If we go up one level and examine ER use from a patterns level, we may discover that certain areas of a city seem to have higher emergency room needs. We may try an adaptive response and increase ER capacity in those regions. If diversion rates are high, we can also find out where the ambulances are being diverted from and try to enhance capacity there.

At the systemic structure level, we can begin to explore why certain regions have an increased need for ER’s. We may discover, for example, that 40% of the ER admissions are children’s poisonings, because a large percentage of the community cannot read English and all warning labels are printed in English. By redrawing the boundary of the ER issue to include the community, we can take actions that will change the inflow of patients. Electrical utilities have been doing this for some time. Instead of building another expensive power plant to supply more power, they are working with customers to reduce the demand for power.

The highest leverage lies in clarifying the quality of life we envision for ourselves and then using that as a guide for creating the systemic structures that will help us achieve that vision.

At a community-wide level, we may want to explore the question ‘What is our shared vision of the role our healthcare system plays in our lives?” Perhaps the resources that are going into ER could be better utilized elsewhere, such as community education and prevention programs. The highest leverage lies in clarifying the quality of life that we envision for ourselves and then using that as a guide for creating the systemic structures that will help us achieve that vision.

The basic message of the “Levels of Understanding” diagram is the importance of recognizing the level at which you are operating, and evaluating whether or not it provides the highest leverage for that situation. Each level offers different opportunities for high-leverage action, but they also have their limits. The challenge is to choose the appropriate response for the immediate situation and find ways to change the future occurrence of those events.