Nine years ago, I became executive director of the Texas Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD). This nonprofit organization has a compelling mission: to improve learning at the elementary, high school, and college level throughout the state of Texas. At the time I joined Texas ASCD, the state legislature had just removed days set aside in the calendar for teachers’ professional development. Our board of directors commissioned me not only to get those days back but to find ways to improve professional development overall for teachers.

As I began lobbying state legislators to designate more days for teachers’ learning, I discovered something surprising: Teachers were lobbying to keep the days to a minimum, and then only for classroom preparation! How can professionals who have devoted their careers to learning be opposed to learning for themselves, I wondered. I took this question to the commissioner of education. Together, we agreed to get to the bottom of the issue.

Probing Teachers’ Resistance

Synchronicity was at work. During this time, a man came to my office with a survey tool that he called the In-Depth Probe (IDP). He said, “So often, surveys only tell us how many people think or feel a certain way. But they don’t tell us why. The IDP gets to the why.” My initial interest intensified when he said that over 95 percent of the people he called agreed to talk with him — some for over an hour.

Impressed, we commissioned him to do an IDP of Texas teachers, with an eye toward finding out why they opposed professional development. The results of the IDP revealed some startling facts. For one thing, the teachers were not against professional development after all; they actually wanted more of it. But they didn’t want what they had been getting — canned presentations about topics that had little relevance to their needs.

Instead of addressing [teachers’] challenges, typical professional development opportunities focused on implementing particular teaching programs and the latest fads.

And what were their needs? As it turned out, their requirements centered solidly on how to work with increasingly diverse students, how to design their teaching to meet students’ different needs, how to work with parents and administrators, and how to use new technologies effectively. But instead of addressing these challenges, typical professional development opportunities focused on implementing particular teaching programs and the latest fads.

I convened a group of professional development leaders to discuss the implications of these findings. After the team mulled over the IDP results, they expressed disappointment in the report. One of them said, “I did my dissertation fifteen years ago, and there’s nothing in this report that wasn’t in my dissertation.” In other words, these leaders knew what to do, but they weren’t doing it.

Why? That question led to our next IDP, this time in conjunction with the Texas Staff Development Council and the Texas Education Agency. We queried staff developers, principals, regional service center leaders, and university professors. The probe revealed that these leaders found it virtually impossible to design effective professional development experiences for others when they had never experienced effective professional development for themselves.

In 1998, the Association of Texas Professional Educators conducted a third IDP. The findings were no different from the first study — with one exception: Staff developers were asking teachers what they needed. However, they still weren’t designing development opportunities to meet those needs.

Mapping Systemic Forces

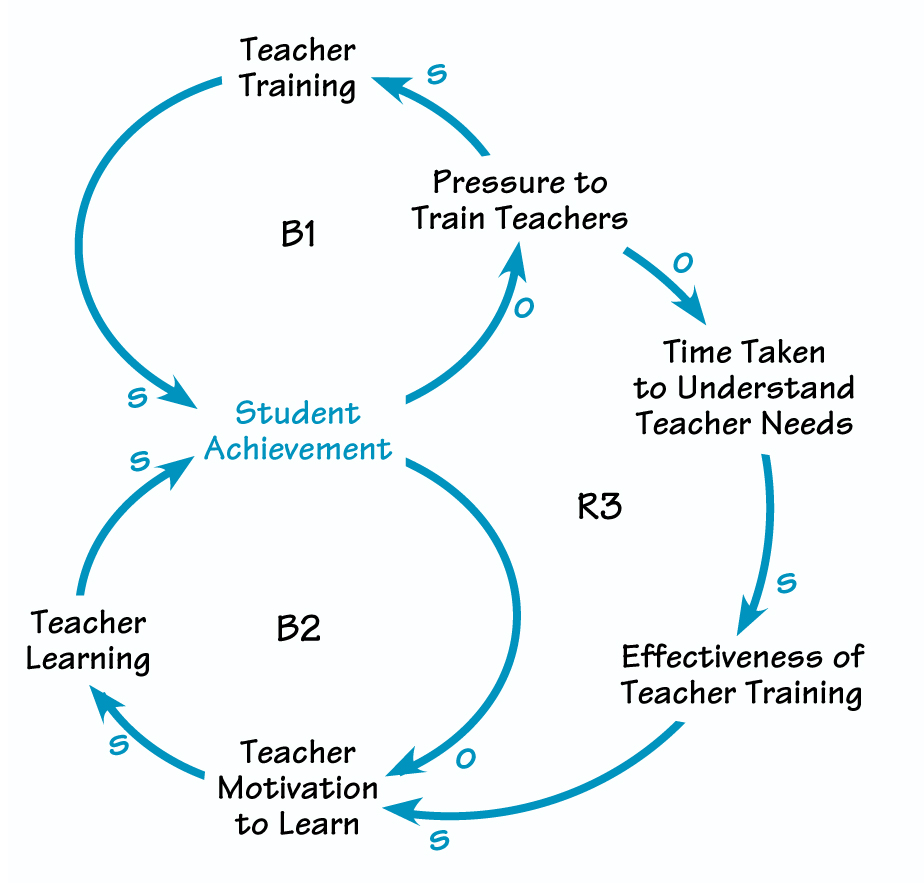

Clearly, it was time for change. I called the leaders of the three organizations that had conducted IDPs. We agreed to meet monthly, to stay at the table for as long as it took to grasp the problem, and to commit to large systems change in professional development practices in Texas. During our gatherings, we asked ourselves, “What forces are holding the current system in place?” We drew a causal loop diagram to capture our various perspectives. The image that emerged depicted a dense, confusing system. We looked closely at it and asked ourselves, “Is a systems archetype at work here?” When we viewed our diagram again through this “lens,” we could see the telltale signs of “Shifting the Burden” (see “Shifting the Burden to Teacher Training” on p. 8).

In this archetype, a problem symptom (in this case, a drop in student achievement) prompts a solution (teacher training) that seems to ease the symptom but that doesn’t get to the root of the problem (B1). In our example, educational development leaders were so sure that their training ideas would fix the problem that they didn’t even look for a more fundamental solution. Members of the group agreed that increasing educators’ intrinsic motivation to learn would provide a more enduring answer to the problem of declining student achievement (B2).

The problem with a “Shifting the Burden” situation is that resorting to a symptomatic solution leads to side-effects that actually damage the ability of the people involved to implement a more fundamental solution. In our case, pressure to train teachers means that professional development leaders take less time to assess teachers’ true needs (R3). Taking this sort of short cut reduces the effectiveness of teacher training, further decreasing teachers’ motivation to learn.

SHIFTING THE BURDEN TO TEACHER TRAINING

Finding Leverage for Change

Where is the leverage for change in this dilemma? We decided that we needed a wedge to break open the system and help us truly address the problem symptom of declining student achievement. As it turned out, synchronicity kicked in once more. The key variable in our case was “teachers’ intrinsic motivation to learn.” Just as we turned our attention to this factor, a board member faxed me a copy of the American Psychological Association’s “Learner-Centered Psychological Principles: A Framework for School Redesign and Reform.” This article contained a section on intrinsic motivation to learn — information that injected new life into our efforts.

Our research had hinted at the fundamental solution to our problem, but we hadn’t been able to hear it. The solution we gleaned from this article centered on applying the enablers behind intrinsic motivation to every aspect of educators’ professional development. According to the American Psychological Association, “Intrinsic motivation is facilitated on tasks that learners perceive as interesting and personally relevant and meaningful, appropriate in complexity and difficulty to the learners’ abilities, and on which they believe they can succeed. Intrinsic motivation is also facilitated on tasks that are comparable to real-world situations and meet needs for choice and control.”

We decided that if we could find ways to enable these forces that drive intrinsic motivation, educator learning would increase. Perhaps we could establish small learning groups in which teachers could explore questions such as “What do our students need us to learn?” and then design ways to accomplish this learning. This would in turn yield greater student learning and kick the entire organization into a pattern of escalating, continuous learning.

And again, synchronicity helped us. In August 1999, a curriculum director commissioned me to design and implement a process for collaborating more closely with principals and central staff on curriculum and learning issues. I decided to work with them in the same way that I envisioned they might work with teachers — by creating a context in which they could learn together. First, we established a safe space for learning, in which participants could engage in their best thinking. We did this by telling true stories about “growing toward” our desired change, practicing speaking without opinion, listening without judging, asking probing questions, and refraining from giving advice. Then we used a variation of Chris Argyris’s Left-Hand/ Right-Hand Column, which helped us to share our real opinions with one another respectfully. Next we talked honestly about the issues that are holding educators in place, impeding their own learning and that of their teachers.

This conversation generated much thinking. However, as with many large-system change projects, the road has been rocky in places. Immediately after this session, the old political system of mistrust, gossip, and tattling reared its head again. Now we are taking a two-month pause, to give our emotions time to rest.

Synchronicity is still at work. This article is coming at exactly the right time, as we enter a new phase in the change process.

Nancy Oelklaus is the executive director of Texas ASCD and will become president of the Education Division of Entrepreneurial Systems, Inc., after July 1. She can be reached at noelklaus@aol.com.