No systems thinker worthy of the name would argue that a single cause, close in time and space, produces a single result in any complex system. Yet that thinking governs how most of us think about relationships and the troubles they sometimes encounter. When upset, even the best system thinker among us automatically reasons: When you did that, it made me feel this.

TEAM TIP

Use the “Anatomy Framework” presented in this article to understand — and change — the patterns of interaction that lead upsetting events to recur in your group.

Indeed, I watched this logic entrap the managers and professionals at one firm in a debilitating conflict that lasted for years. Despite everyone’s grasp of systems thinking — they even taught it to their clients — they were all equally convinced that the other guy was causing the impasse. In their minds, cause and effect was linear: When management (or the professionals) did this, they caused that. With the cause of their difficulties now firmly placed in the other guy’s hands, they each waited for the other to change before changing themselves. Stalemate.

When it comes to relationships, it’s small wonder most of us still think this way. As Peter Senge points out in The Fifth Discipline, the roots of this straight-line thinking go back millennia, and changing it won’t be easy. Nor will it be helped by most advice today on how to handle people and relationships well. Almost all of this advice offers the same formula: “When you did X, it made me feel Y.” This formula, which looks innocuous enough on the surface, reinforces thinking that makes relationships grow weaker, not stronger over time.

In today’s fast-paced, interdependent world, relationships among people (not just things or units) matter — a lot.

For 25 years, I’ve been searching for another way of thinking about relationships and the difficulties they encounter — one that makes it easier for people to use those troubles to strengthen their relationships and to learn, change, and grow. That search lies at the heart of my work, and what I’ve found holds startling implications for how to create and sustain strong relationships and stellar teams. Join me as I retrace what I’ve learned; you may be surprised by what you discover on this seemingly well-trodden ground.

Relationship Matters

Perhaps it goes without saying, but in today’s fast-paced, interdependent world, relationships among people (not just things or units) matter — a lot. More and more, people in one part of an organization must work seamlessly with people in other parts if they’re going to get anything done, at least in a timely fashion. As a result, the world (not just our boss) has placed a premium on our ability to navigate tricky, mixed-motive relationships well and without wasting time.

Even the Wall Street Journal, hardly a bastion of touchy-feely thought, has heralded the importance of what they call people skills: “For years, the study of management behavior played second fiddle to quantitative analysis,” a 2006 WSJ article begins. “Now, executives hire coaches to hone their people skills. And business-literature trackers say books on topics like the psychology of leaders outsell tracts on hardnosed subjects like supply-chain management.”

Small surprise, then, that books geared toward developing people’s social competence are selling like hotcakes. People are hungry for guidance. But just what kind of guidance are they getting?

To see, let’s look at a brief passage in Daniel Goleman’s groundbreaking book Emotional Intelligence (Bantam Books, 1995), not because the book’s so bad, but because it’s so good. In fact, it’s hard to find better. Among the many examples Goleman uses to illustrate emotional intelligence, he offers the statement, “When you forgot to pick up my clothes at the cleaners, it made me feel like you don’t care for me.” To underscore the emotional intelligence behind such a statement, he compares it to another way of communicating similar meanings: “You’re always so selfish and uncaring. It just proves I can’t trust you to do anything right.” Without a doubt, the first statement, when compared with the second, comes out looking mighty good.

As Goleman points out, instead of attacking the person’s character, the first statement refers to specific behaviors and feelings and produces less defensiveness as a result. So far, so good.

But let’s take a closer look at the logic underlying the statement, “When you forgot to pick up my clothes at the cleaners, it made me feel like you don’t care for me.” At work in that statement are two assumptions about cause-effect relationships within human relationships.

- The first assumption is that one person’s actions — close in time and space — can singlehandedly cause another person’s reactions. Causes more distant in time and space are not relevant or important causal factors.,/li.

Though highly shared, these assumptions raise a few questions and pose a few problems when it comes to relationships.

One Person’s Actions Cause Another’s Reactions

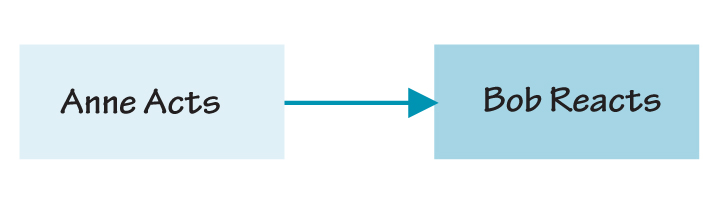

Let’s take the first assumption and call the people in the relationship Bob and Anne. If we mapped the cause-effect logic underlying this assumption, it would look like “Simple Cause-Effect Logic,” depicted in the first diagram.

According to this diagram, it’s all pretty simple: Anne’s forgetting made Bob feel uncared for. This makes sense if we believe two things are true:

- Bob could react no other way to Anne’s actions. She made him react one way, not another.

- Bob’s reactions were caused by Anne’s actions alone. No other factors came into play.

Let’s explore the first notion. While it’s not unreasonable for Bob to feel uncared for when Anne forgot his clothes, it’s not the only reaction possible. Someone else might wonder if Anne was too overwhelmed to remember and grow concerned. As we all know, different people react differently to the same behavior, depending on what it means to them. So it’s hard to imagine how the first statement could be true — that is, how Bob’s feeling uncared for was an inevitable consequence of Anne’s forgetfulness. Any number of reactions may be reasonable in a given culture, and none of them is a necessary consequence of another person’s behavior. That means another, less obvious causal factor must also be at work: Bob’s interpretation of what Anne’s behavior means.

SIMPLE CAUSE-EFFECT LOGIC

No systems thinker worthy of the name would argue that a single cause, close in time and space, produces a single result in any complex system. Nevertheless, that thinking governs how most of us think about relationships and the troubles they sometimes encounter.

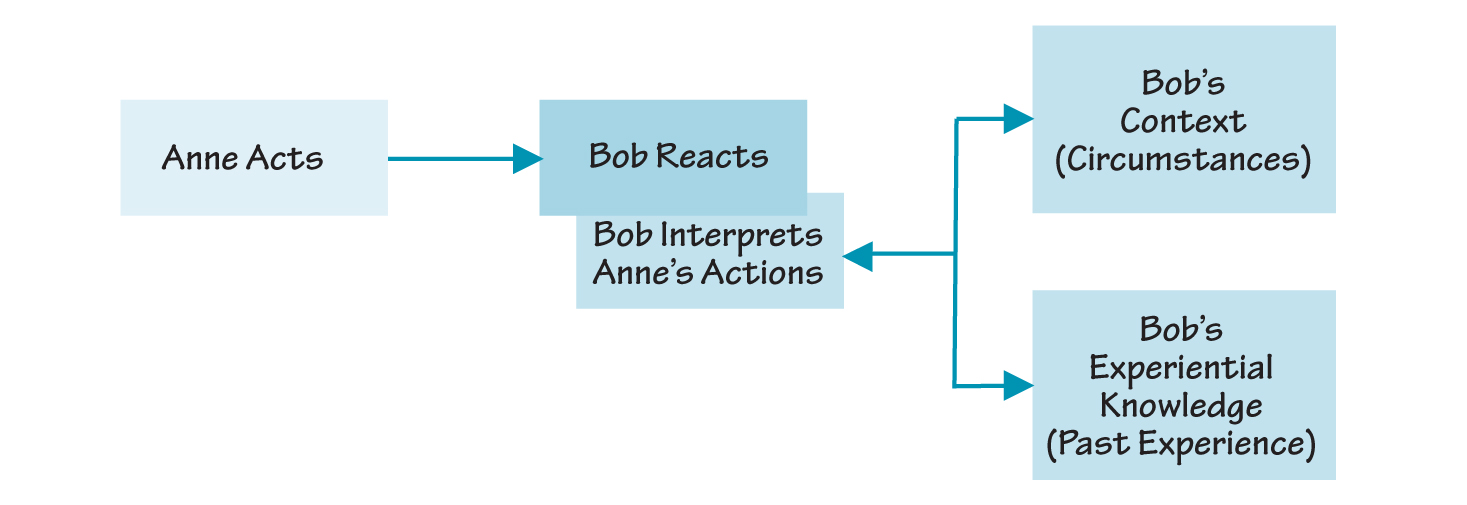

This brings us to the second notion: that Anne’s actions alone caused Bob’s reactions. But if Bob’s interpretation of Anne’s actions also played a role, it’s hard to see how this could be true. Doesn’t it suggest that another factor — Bob’s interpretation of Anne’s behavior — is also at work? Maybe. You could argue that Bob’s interpretation was caused by Anne’s actions alone and hence his feelings were, too. But would it make sense to take that perspective?.

Let’s see. All of us know that when things are going well, time is on our side, and people are treating us kindly, we don’t see things the same way or get as upset as we might under stressful circumstances. We give people slack; we overlook slights; we extend the benefit of the doubt. Like all of us, Bob’s reactions are in part shaped by his circumstances — whether his time is scarce, whether others let him down that day, whether he’s feeling well or ill, and whether this is the fourth time Anne has forgotten something. So it’s possible that, under some circumstances, Bob might not have even noticed Anne’s forgetfulness, or at least, not gotten upset about it. This means we have to add yet another causal factor to the equation: Bob’s circumstances — what I call his context. That too plays a role.

But wait, there’s more! Another factor is also at play. No matter what kind of day Bob is having, he’s apt to notice Anne’s forgetfulness more and react more viscerally to it if he associates what happened with past hurts — say, the neglect of an uncaring or forgetful parent. The more we associate current events or people with past ones, the more we’re apt to interpret them in a particular way — say, in Bob’s case, as a lack of care. As an article in BusinessWeek once put it: “If it’s hysterical, it’s probably historical.” Like all of us, Bob has built out of experience a large stock of experiential knowledge. Without this knowledge, Bob wouldn’t have a clue how to interpret or react to what Anne did — or to what anyone did for that matter. And so we also have to factor into the equation his past experience and what he’s made out of it.

SLIGHTLY MORE COMPLEX CAUSE-EFFECT LOGIC

All told, we now have three factors to add to what was a simple, linear cause-effect equation: Bob’s experiential knowledge, the larger context in which Anne’s forgetfulness occurred, and the way Bob interpreted Anne’s behavior as a result. Once we add these factors, the cause of Bob’s upset grows slightly more complex (see “Slightly More Complex Cause-Effect Logic” on page 3).

This diagram suggests that the first assumption doesn’t hold. It wasn’t Anne’s actions alone that caused Bob to feel uncared for, but a combination of interrelated factors. The implication? Anne didn’t make Bob feel anything; his feelings were the result of a joint venture. Just how much of a joint venture and what kind are the questions we’ll take up next.

The Causal Flow Is One Way

The second assumption is that Bob’s upset has nothing to do with what he’s done; the causal flow is entirely one way. Anne’s actions caused Bob to get upset. End of story. In this story, Bob is not a relevant causal factor, and no attention is given to what caused Anne to “make” Bob upset. In fact, that whole causal chain slips unnoticed off the radar screen. And so it wouldn’t occur to Bob (or to most Bobs) to look for it — though it would certainly occur to most Annes.

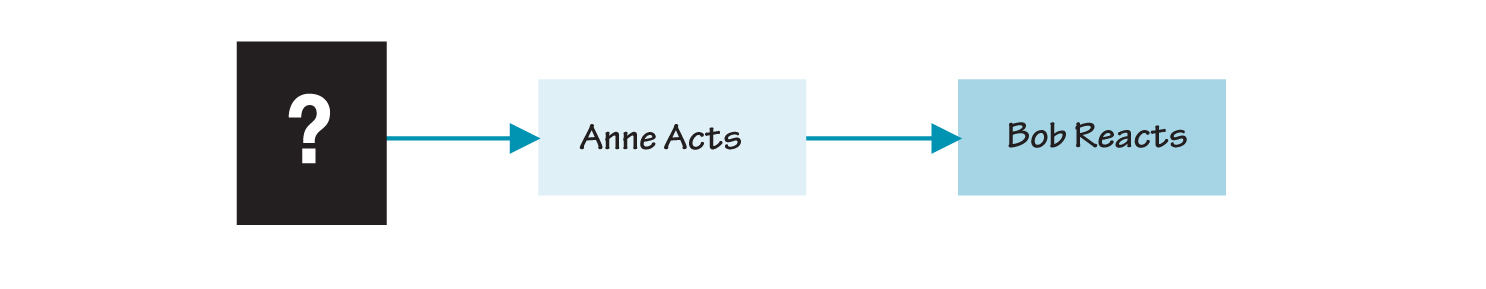

But let’s say we ask the question: What led Anne to forget Bob’s clothes at the cleaners in the first place? Well, then we’d have to modify our original diagram by adding a great big question mark right smack in the middle of a big black box (see “Question Raised by Simple Cause-Effect Logic”).

Absent this question mark, we’re more likely to focus on what Anne did to cause Bob’s reaction and less likely to ask what led Anne to forget — especially since Bob’s statement presumes an answer before even asking: Anne doesn’t care enough about Bob to remember his cleaning. That one factor (Anne’s not caring) caused Anne to forget.

But let’s say that Anne’s actions, like Bob’s reactions, flow from more than one factor. In fact, let’s imagine that over time statements like, “When you forgot my cleaning, it made me feel like you don’t care for me,” contributed to feelings of guilt in Anne. And let’s imagine that Anne spent much of her childhood feeling guilty about not doing what her parents asked her to do, and that she learned to manage her folks by promising to do what they asked, only to let them down and to hear again how disappointed they were, leading her to make more promises and to create more disappointment and guilt, and so on. Not an unfamiliar scenario and certainly possible.

Finally, let’s suppose that as an adult, Anne hates disappointing those she loves and feels intense guilt when she does. Like all of us, Anne manages uncomfortable feelings like these by doing what she knows how to do best — in her case, promising to do things she either doesn’t want to do or can’t do. In fact, when she promised to pick up Bob’s clothes, she might have been overwhelmed by all the commitments she’d made: picking kids up at school, meeting deadlines at work, grabbing food for dinner. Overwhelmed by these self-imposed demands, she forgot Bob’s cleaning. To Anne, it didn’t mean she didn’t care for Bob; it meant she cared too much.

QUESTION RAISED BY SIMPLE CAUSE-EFFECT LOGIC

The Plot Thickens

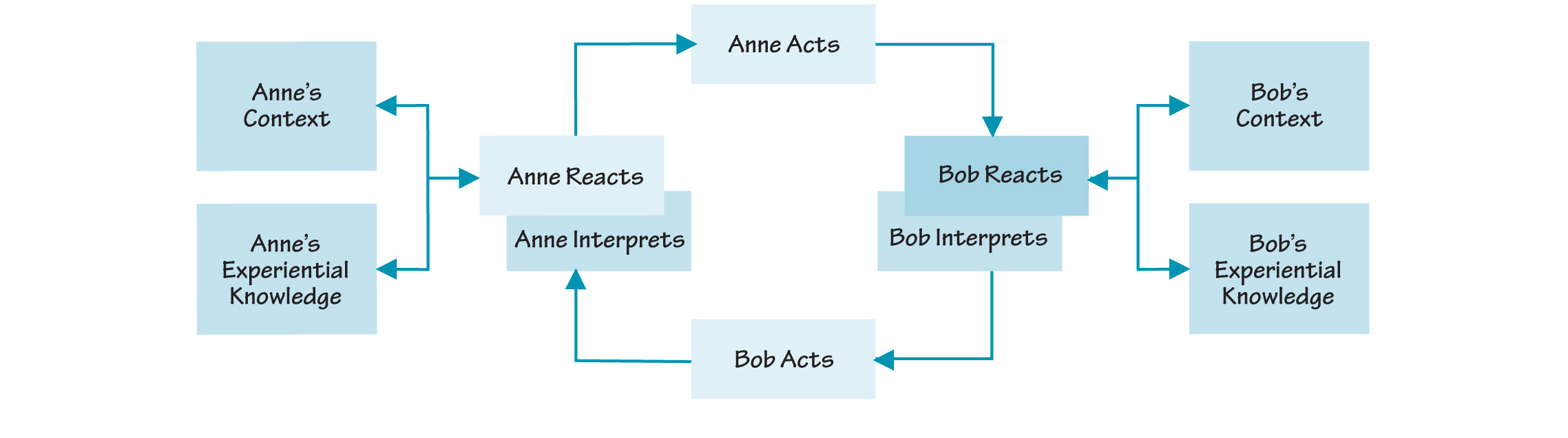

In this imaginary scenario, Anne didn’t simply forget, but nor did she forget simply because she didn’t care for Bob. Though we don’t know what led Anne to forget, we can surmise with a good deal of confidence that it was a combination of factors: Bob’s prior actions (perhaps saying things such as “You make me feel uncared for”), the way she interpreted and felt about Bob and about herself in relation to him (Bob as judge, herself as guilty), her context (multiple demands), and what she’d made of past experience (learning to overpromise to manage others’ disappointment and her own guilt and anxiety). Whatever the particulars, the underlying logic remains the same: Just as the causality surrounding Bob’s reactions is complex, so is that surrounding Anne’s actions.

If we now pull all these factors together — those affecting Anne’s actions as well as Bob’s reactions — a more systemic dynamic comes into view (see “A More Systemic Dynamic Comes into View”).

According to this diagram, Anne’s forgetting didn’t by itself cause Bob to feel uncared for, even though that action may be closest in time and space. Indeed, it suggests that Bob’s reactions play a dual role — as both cause and effect — in a complex dynamic between Bob and Anne.

That dynamic consists of a whole host of factors, all of them interacting together in a circular fashion to produce the feeling in Bob that Anne doesn’t care about him. With this more systemic understanding of the event, Bob and Anne can now work together to alter it, making it less likely that events like this one will repeat.

The Anatomy of a Relationship

My research on relationships in top teams suggests that upsetting events within a relationship almost always shed an important light on how a relationship works — or fails to work. Anne’s forgetting Bob’s cleaning and Bob’s feeling uncared for is not an anomaly, especially since it upset Bob enough to raise it. Events like this are what give Bob and Anne’s relationship its distinctive character, one they can intuitively recognize but can’t easily describe. As a result, upsetting events like this one are apt to recur.

Yet given current advice, the best they can do when it recurs is to say once again, “When you did that, it made me feel this.” While that’s a whole lot better than saying, “You’re always so selfish and uncaring. It just proves I can’t trust you to do anything right,” it won’t take Bob and Anne where they need to go to alter the dynamic.

If anything, it could make matters worse. Anne might easily respond, “Yes, I can see that, and when you tell me you feel uncared for when I make a mistake, that makes me feel judged and guilty.” Granted, they would now understand how they each “make” the other feel, but they wouldn’t have a clue how their relationship works such that one of them feels uncared for and the other guilty.

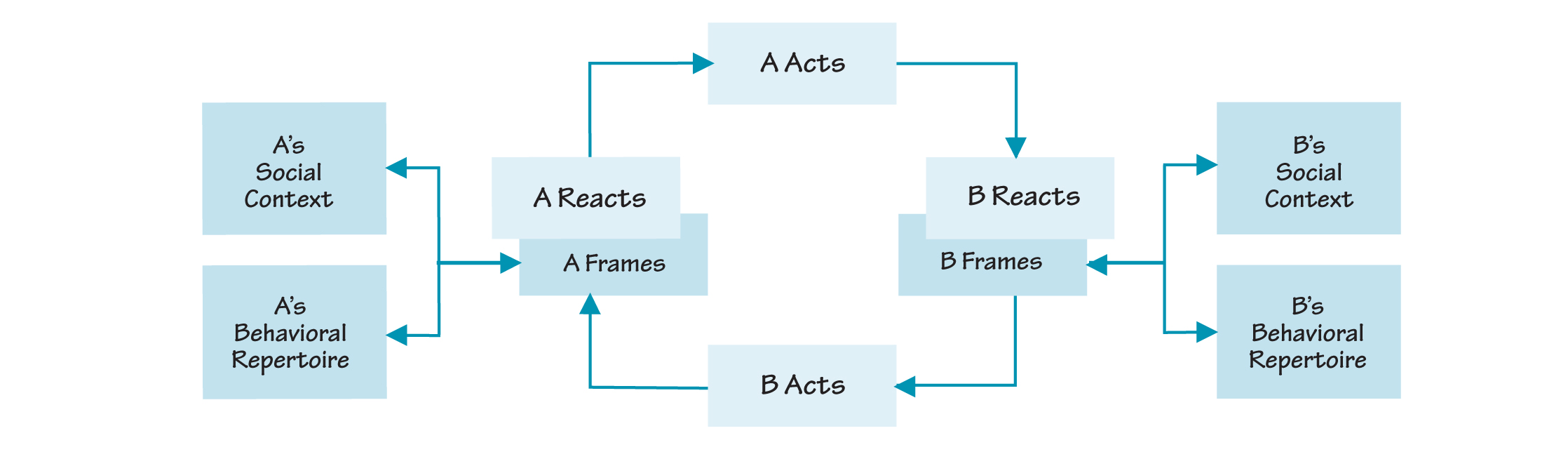

The “Anatomy Framework,” used above to capture Bob and Anne’s dynamic, helps people understand the patterns of interaction that lead upsetting events to recur (also see “The Anatomy Framework” on page 6). These patterns, once they take shape and take hold, define how a relationship works — what I call the underlying anatomy or structure of a relationship. Within that structure, people’s interlocking actions and reactions create a particular pattern, while their respective social contexts and experiential knowledge lock that pattern into place. As all good systems thinkers already know, events follow.

A MORE SYSTEMIC DYNAMIC COMES INTO VIEW

You might notice that the Anatomy Framework on the next page uses some new terms. Instead of the word “interpret,” I use the word “frame”; and instead of the words “experiential knowledge,” I use the words “behavioral repertoire.” I use “frame” to refer only to those repetitious ways we have of interpreting others and ourselves in relation to them. Oh, that’s just Frank. You know how he is. He always thinks he’s right and he never cares what others say. All I can do is play the good wife and humor him. I use the term “behavioral repertoire” to refer not only to the experiential knowledge we bring to events but to the interpretive strategies we use to apply and revise that knowledge. The two together — our largely unconscious experiential knowledge and our largely tacit interpretive strategies — combine to define our behavioral repertoires: our characteristic ways of responding to others.

Had Bob and Anne used the Anatomy Framework to explore Bob’s reactions, they would have seen that his feelings said something about him as well about Anne, and something about the informal structure the two of them had created together. This more relational way of thinking opens up eight times the number of options for changing dynamics that cause upsetting events to occur and recur. With this way of thinking, Anne and Bob can each revisit and revise either their actions, or their reactions, or their social contexts, or their experiential knowledge. Depending on how many and which factors they address, they will alter the dynamics of their relationship to a greater or lesser extent.

Thinking about relationships in simple, cause-effect terms implies only one solution: One or the other person has to change — usually the other person. All this does is give rise to what I call the “Waiting Game,” in which each person waits for the other to change before changing themselves. When you win this game, everyone loses.

My Relationship Made Me Do It

My research on team relationships suggests that people who take a relational perspective build relationships that grow stronger over time, while those who think in more simplistic, either/or terms build relationships that grow more fragile. Even so, many people question whether it’s wise to think in relational terms. What will happen to notions of personal responsibility? they ask. How can you hold anyone accountable for anything if you focus on relationships? After all, you can fire or sue a person, but not a relationship. You’re better off keeping your eye on individuals, they argue, where responsibility can be clearly assigned and appropriately taken.

THE ANATOMY FRAMEWORK

- Actions and Reactions. Actions refer to what someone actually says and does, while reactions refer to what someone actually thinks and feels in response to what the other person says and does. Each person’s actions make the other person’s reactions more explicable (see the light boxes in the diagram and the way they reinforce each other).

- Frames. The interpretations embedded in our reactions, making some actions seem obvious and others impractical (see the darker boxes behind “A Reacts” and “B Reacts”).

- Social Contexts. The contextual backdrop — formal roles, time constraints, historical events — against which some triggering event occurs, prompting the need to respond (see the darkest boxes with the two-way arrows running into “A Frames” and “B Frames”).

- Behavioral Repertoires. The largely unconscious experiential knowledge and interpretive strategies that define the range of responses people have at their disposal for framing and acting in different social contexts, once triggered by some event (again, see the darkest boxes with the two-ways arrows running into “A Frames” and “B Frames”). As the arrows suggest, people’s behavioral repertoires both shape and are shaped by their social contexts. Together the two govern the way people frame situations, leading them to react and act toward each other in some ways and not others.

These four elements combine to give a relationship its distinctive character, one we intuitively recognize but have difficulty describing or changing without the proper tools.

It’s a good point. There’s already enough blame-shifting in organizations without adding another excuse: “It wasn’t me. My relationship made me do it.”

But taking a relational perspective doesn’t preempt people from taking responsibility or from looking at what each individual does to create a relationship neither likes. Far from diluting responsibility, when you put the relational back in relationships, you take excuses off the table. No more, “He made me do it.” Instead, people assume personal responsibility not just for themselves but for the relationships they together create and for the impact those relationships have on themselves, those around them, and their organization.

Note: You can learn more about taking a relational approach in Divide Or Conquer: How Great Teams Turn Conflict into Strength (Portfolio/Penguin Group, June 2008).

Diana McLain Smith is the author of Divide Or Conquer: How Great Teams Turn Conflict into Strength (Portfolio/Penguin Group, June 2008). She is a partner at the Monitor Group, a global management consulting firm, where she teaches, consults, and conducts research, as well as a founding partner of Action Design, which specializes in organizational learning and professional development. Diana has taught courses and delivered lectures at the Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation, the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Boston College’s Carroll School of Management.

NEXT STEPS

- Identify a situation in which a colleague triggered a negative reaction on your part. Think about how you might have worded the encounter, using the formula: “When you did X, it made me feel Y.”

- List the past experiences and circumstances that led you to react the way you did.

- List the past experiences and circumstances that may have led the other person to act the way they did.

- Using the relational perspective outlined in the article, look at how you might use your deeper understanding of this one incident to change the patterns that cause upsetting events to recur with this person. How might you join forces to change the underlying dynamics and build a more productive partnership?