In the October “Systems Thinking Workout,” we presented a scenario involving part-time employment in Germany. The article explored the potential ramifications of a new policy by which the German government has begun taxing income earned through second jobs.

Phil Ramsey, who teaches at the College of Business at Massey University in New Zealand, offered the following analysis of the systemic dynamics at work in this scenario. In preparing his analysis, Phil also consulted with Rolf Cremer, who is head of Massey’s College of Business—and who also happens to be a German economist. Here’s Phil’s response:

This case might well be more about the German government’s employment policy than about tax policy. Taxation is just an instrument that the government is using to achieve its employment goals.

In thinking about this case, it helps to appreciate the cultural assumptions operating in Germany. Germany has preferred to create work that is knowledge intensive, often in production of capital goods. For many Germans, the term job is pejorative because it implies work that has little value and that is done only for money. By contrast, the term work connotes positions of high value. In this analysis, we’ll distinguish between the “real work” (full time, knowledge intensive, and high paying) that we see German employment policy seeking to create, and the “jobs” (low paid, part time, and low skilled) that may be lost.

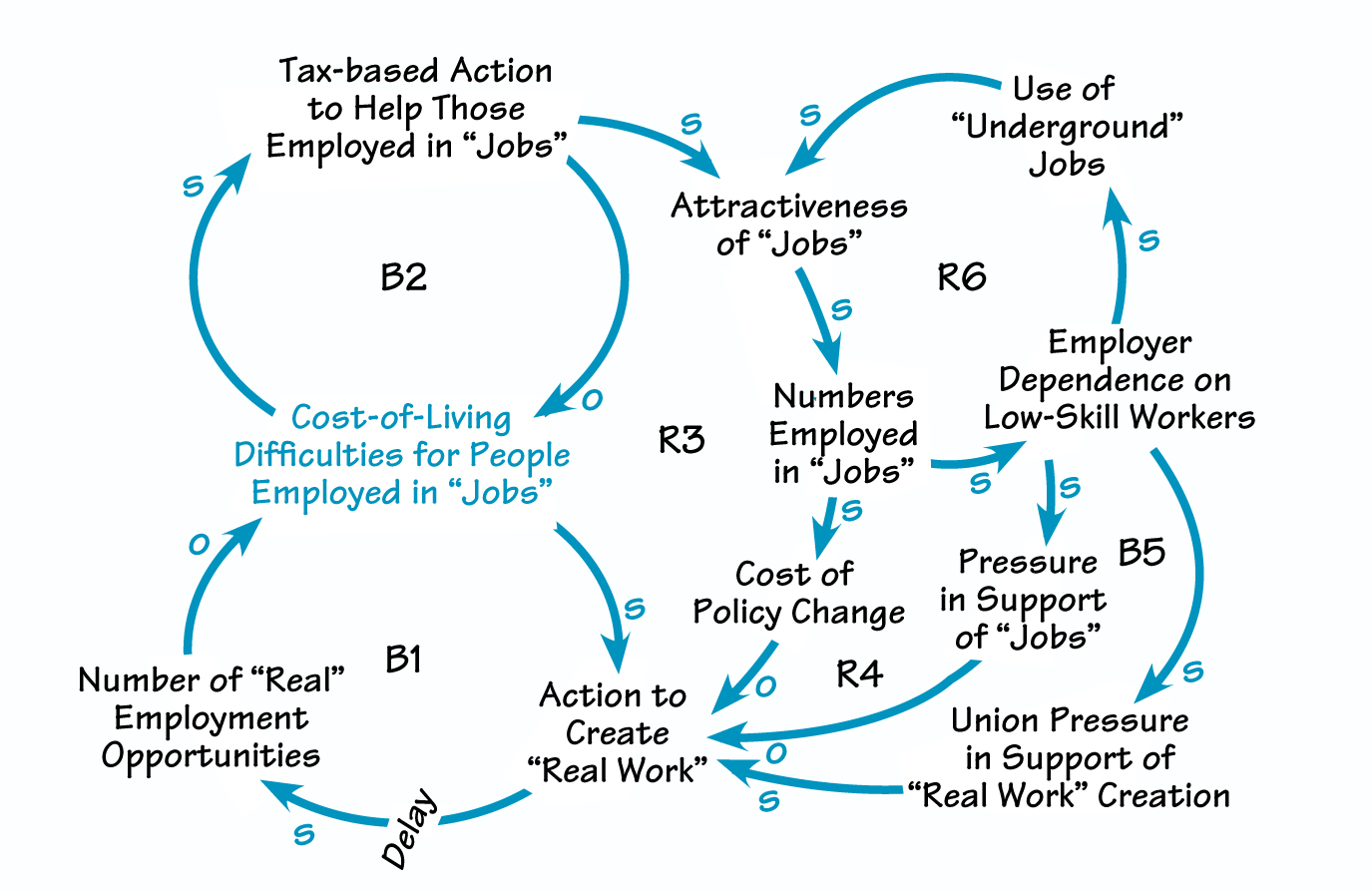

Seen in this light, the case could describe the natural “worse before better” consequences of a shift in policy that encourages the creation of “real work.” People who are not in such arenas of employment—whether because they are unemployed or they are in low-paid/low-skilled jobs—will experience cost-of-living difficulties as a result of this shift. Loop B1 shows the fundamental solution to these difficulties: the creation of more “real” employment opportunities. Creating such work naturally involves significant delays.

In the past, tax relief has allowed low-paid workers to take on second jobs to reduce their cost-of-living difficulties (B2). This course of action apparently has had a number of side-effects—the number of people taking up “jobs” increased (R3). Now, if the German government attempts to alter tax laws to encourage creation of “real work,” the costs—in particular, unemployment for those who were in those “jobs”—will be huge. This, along with employers’ growing dependence on low-skill workers (R4), acts to dampen government enthusiasm for what it sees as the fundamental solution.

The role of labor unions in this scenario is fascinating. They clearly have much to gain from a policy based on knowledge-intensive work creation—they support government action for the fundamental solution (B5). There is therefore a confluence of energy around action to create “real work”: Government policy and union pressure are working to strengthen this variable, while costs and employer pressures work to weaken it. Assuming that it really is a fundamental solution, leverage involves government determination to see the solution through, despite the “worse before better” effects.

Another factor is the growth of “underground” jobs (R6), which may result from government policy to support “real work.” Germans appear to have a preference for “real” rather than “underground” work, so a potential unintended consequence may be growing use of illegal immigrant workers in response to employer demand for low-skill jobs.

“Real Work” Versus “Jobs”

The fundamental solution—creating “real work”—is supported by government policy and union pressure, and weakened by costs of the solution and employer dependence on workers in low-skill, low-wage “jobs.”