Saturn, General Motors’ bold experiment in car manufacturing, is running into troubled times. Revolutionary no-haggle prices and a strong reputation for quality made Saturn an overnight success with consumers. This hot, new car has lured import buyers back to American cars at a time when other GM divisions are suffering from sluggish sales and outdated models. But delivery delays and production problems have troubled Saturn Corporation since its startup, and problems are now being magnified by the high level of demand. According to a recent Business Week article, the company’s relationship with its employees is beginning to show the strain (“Saturn: Labor’s Love Lost?” February 3, 1993).

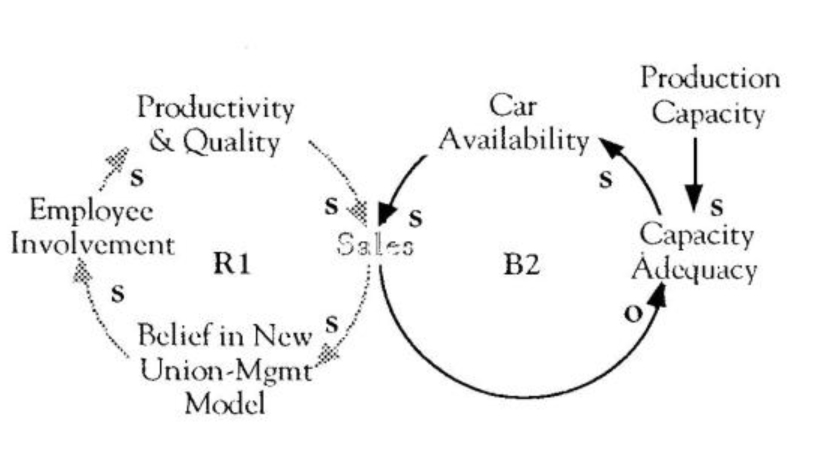

From its inception, Saturn has been one of the “nation’s leading experiments in labor-management cooperation.” Its employees have had an unprecedented amount of control in what happens at the company, from hiring to budgeting. “The enthusiasm this generated among the initial group of 3200 United Auto Workers (UAW) members, mostly hired in 1988 and 1989, has been key in making Saturns amongst the high-quality U.S.-built cars.” Teams of about 15 employees handle all aspects of management, including product development and marketing campaigns; and this involvement has led to higher productivity and increased cooperation (see RI in “Saturn’s Growth Engine”).

Higher production demands have forced changes in Saturn’s personnel strategy, however. To satisfy the increasing number of consumers asking for new Saturn, production is being pushed upwards from 240,000 to 310,000 cars per year. This boost in production is resulting in long workweeks for many employees, and also forcing an increase in the number of new workers. Eighteen hundred people have transferred to Saturn from other GM divisions just since 1990 — and many of these new workers were laid-off from other plants and are looking not for a cooperative environment, but a job.

To make matters worse, Saturn’s management decided to cut by 50% or more “the extensive training for new workers that helped the original work force learn cooperative work methods.” An additional 1000 ex-GMers who have been laid off at other plants will be coming on board, adding further to the dissidents’ ranks.

As a result of these moves, many new hires are not as committed to the original cooperative structure and enthusiasm of the company and are uncomfortable with the closeness between management and union officials. But Saturn’s management is under pressure to move these new workers into position quickly — to relieve employees who have worked 50-hour workweeks for over a year.

Therefore, “instead of first learning basic skills that are crucial to the smooth operation of Saturn’s teams, such as conflict management, new hires initially focus on such job-specific skills as power-tool operation.” Saturn officials argue that training is a luxury they cannot afford. So far, they “doubt that growing employee unhappiness will damage quality or productivity,” according to Business Week. The drop in employee training, however, from 700 hours of training to just 175 hours, could have a significant impact on the corporate culture at Saturn, and perhaps Saturn’s future success.

Solving the present problems may only be the beginning. Saturn will need an additional $1 billion to develop a larger model for their current buyers to grow into. But every dollar spent on Saturn means less support for other GM divisions. Chevrolet, for example, needs to update its outmoded models that are clogging up dealer showrooms, but does not have the resources to do so. Their car and light truck market share may continue to drop further than the 4.7% it has already declined in 1992.

Discussion Questions:

- How are the physical and personnel limits affecting Saturn’s success?

- How quickly can Saturn adjust those limits relative to the rate of sales growth?

- What actions should General Motors and Saturn take to ensure long-term success?

- What kinds of deep-rooted assumptions (e.g., “there will always be a Chevrolet division”) must GM face in making investment decisions about all its car divisions ?

Saturn's Growth Engine

Saturn’s current success is being fueled by past investments in a new union-management model that is creating higher quality cars and increasing sales (RI).

Saturn Corporation began with a vision: to create a laboratory in which Former GM Chairman Roger Smith could “reinvent” his company. In order to develop a culture of cooperation and commitment in the factory, part of that plan was to experiment with radically different labor practices. Saturn’s management worked hard to strengthen and maintain close management-union ties.

According to Business Week, Saturn’s United Auto Workers contract gives workers a voice in all management decisions, linking 20% of all pay to quality, productivity, and profitability. As a result of heavy investment in recruiting and training, employee involvement has become an important factor in its success, enabling Saturn to maintain high standards of quality and production. And as the car’s winning reputation for quality has demonstrated its success in the marketplace, commitment to the company and its new union-management model has increased. Last fall, for example, workers balked at a production increase that resulted in higher defects, forcing the company to ease off on its production goals.

Saturn's 'Limits to Growth'

Capacity Constraints

Though Saturn’s employees are thrilled with its success, the company also appears to have been caught off-guard. In July 1992, when Saturn dealers sold twice as many cars per dealer as the next leading manufacturer, Saturn’s vice president for o sales acknowledged that the numbers were far greater than expected. In September, the company was forced to launch an ad campaign to explain the drastic shortage of cars — a six-to eight-day supply of cars nationwide versus the average 65 — that forced many customers to wait up to 8 weeks for delivery (“GM Saturn Ads Request Buyers to Be Patient,” The Wall Street Journal, September 25, 1992).

Though the campaign put the best possible spin on the situation, telling consumers Saturn would not sacrifice quality for the sake of production goals, the shortage sent the company scrambling for ways to ease the production limits that were curtailing sales (B2 in “Saturn’s ‘Limits to Success'”).

The Seeds of failure

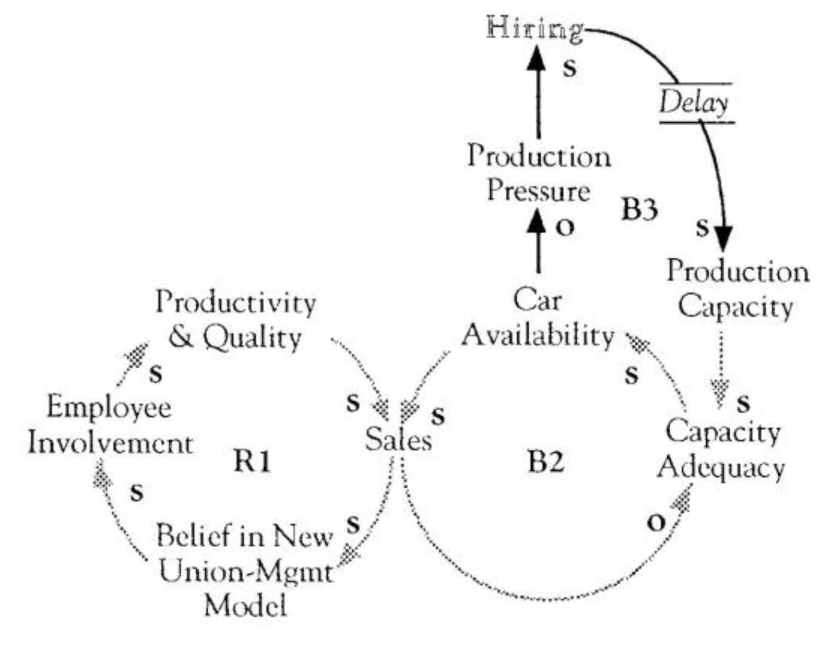

Saturn’s current predicament is, in part, the result of a mismatch between the rapid rise in sales and their ability to hire and train the workers needed to meet the demand (see loop B3 in “Capacity Constraints”). Saturn’s unique employee involvement — the key to much of its success — requires far more time investment in recruiting and training than a traditional union shop.

Tremendous production pressures, however, have forced Saturn’s management to try to boost production with an array of initiatives to increase worker capacity. None of their actions, however, can alter the inherent time delay required to alleviate the pressures. In trying to meet customer demand that exceeds their current capacity, management is bypassing their carefully designed process of recruiting the “right” people and training them in basic teamwork skills, and is focusing instead on training them in specific skills that are needed to run the production line.

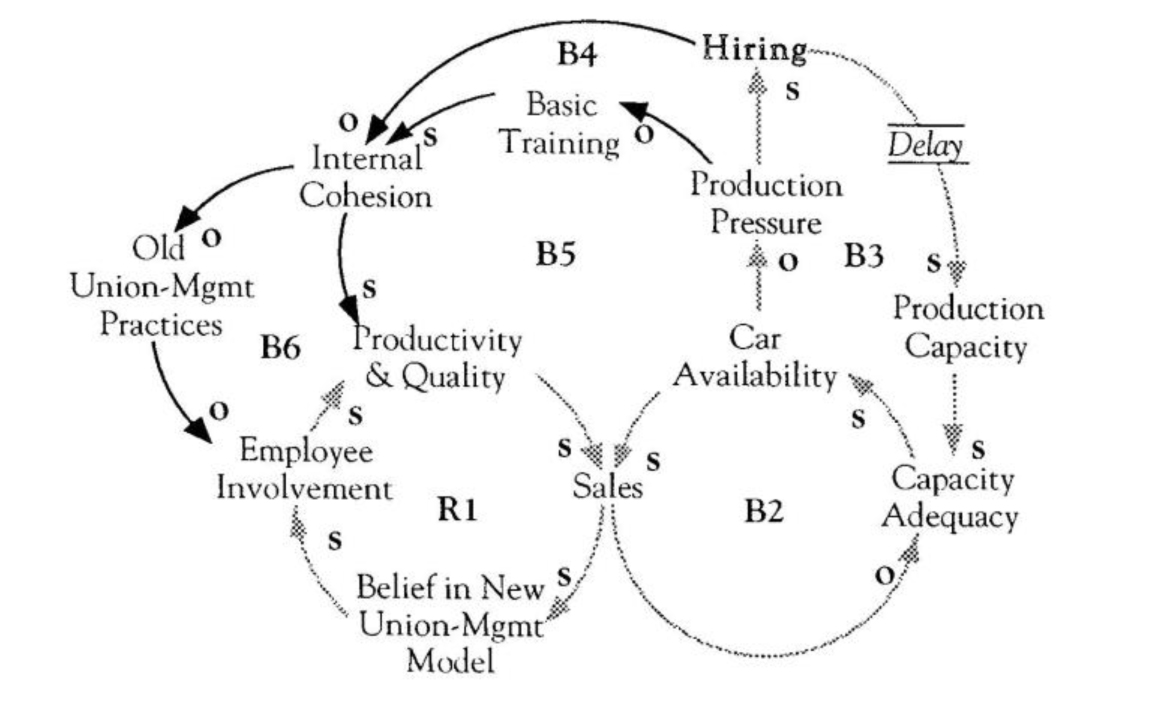

Although these practices seem to have alleviated the short-term pressures, over time they may erode the internal cohesion, resulting in an uncooperative workforce, jeopardizing production quality and perhaps leading to a decline in sales (B5 in “Reversing the Engine of Success”). Another side-effect of decreased training and community-building could be the return to old union-management relations, which would unravel the unique practices that have been the hallmark of Saturn’s success (B6). Any one of these balancing loops can kick the reinforcing engine in reverse, creating a downward spiral of decreasing employee involvement, quality, and sales (RI). With these actions, the seeds of failure may already have been sown.

Options

In this case, GM has at least three choices:

1. Stick with their current plans and keep pumping up the car volume. In doing this, they risk running into the problems covered above.

2. Slow down the ramp-up to a manageable pace but keep prices the same. This will help them preserve quality, but increase financial pressures. They may also lose customers who will tire of waiting.

3. Ramp up only as fast as they can while still preserving the team spirit that has been the key to success and raise prices enough to boost profits by the same amount as would increasing production. They may lose some customers, but it will provide them with the financial breathing room to prepare for the future.

From the “Limits to Success” perspective, the only real choice is option three. Instead of raising production to 310,000 cars per year, increasing the price by $500 per car can increase profits by $120 million on the current annual volume of 240,000 cars. (That would just about equal the profits they would gain by trying to boost an extra 70,000 units.)

Making unilateral price increases, however, may not be something that General Motors is willing to do. American automakers have become very reluctant to alter prices in recent years, allowing Japanese automakers to call the pricing shots. This time, however, GM appears to have a winner that is beating the Japanese at their own game. As Hideyo Miyano, engine research head at Honda Motor Company’s R&D unit, said in a Business Week article “We are very worried, and that’s not simply flattery” (“Saturn,” August 17, 1992).

It’s possible that GM’s worldview has been so conditioned by a decade of inferior quality (relative to the imports), raising prices may be an option they cannot bring themselves to take. Yet, when the Japanese cars offered superior quality, raising prices did little to slow the demand for their cars, and Americans seem eager to buy a quality American-made car. GM appears to be ignoring a fundamental economic fact — when demand exceeds supply, raise prices. This is not just a short-term profit-taking action, but a sound strategy for putting quality as the highest goal and providing the financial means to invest in Saturn’s continued success.

Reversing the Engine of Success

Investing for the Future

Surviving the immediate crunch is only the beginning. The time has come for Saturn to re-examine its strategy and ask some key questions. Tight purse strings at GM and pressure to start bringing in profits may pose the question of whether Saturn will be able to make the necessary investments now to deal with its growth over the long-term. With other GM divisions such as Chevrolet vying for support CO update their models, Saturn may find it difficult to bring in additional funding that will be needed not only to increase capacity, but also to build fresh models and remain competitive with the Japanese.

With a widening customer base and strong engines of growth, Saturn may climb out of the red this year. But this does not guarantee continued success. In the long-term, both Saturn and GM must decide if and how Saturn is going to fit into GM’s overall corporate strategy. What kinds of investments will be required to meet demand if sales should double? Is there a willingness to make the investments necessary to develop a fuller Saturn line? Should one of the other GM divisions (such as Chevrolet or Pontiac) be phased into Saturn or phased out altogether? Given GM’s current financial position, tough choices may need to be made to ensure a bright future of some of the divisions, versus a mediocre future for all of the divisions.

As Saturn may discover, the most dangerous thing a company can do in this situation is to take actions that will undermine or reverse the virtuous growth engine that is producing its success. It is absolutely crucial during this phase to remain focused on the long-term vision of the enterprise, and not succumb to the pressures of the moment.