I don’t know how any parent could stand to send his or her child off to a crumbling, dirty school with underpaid teachers and hostile, possibly armed, classmates. If it were my kid, rather than do that, I’d exert some “school choice,” whether the government sanctioned it or not.

That’s why the push toward state-supported school choice is so insidious. The “choice” it gives every parent—do what’s best for society in the long term or for my kid right now—can only be made one way. My kid right now.

School choice promoters don’t think they’re creating that dilemma. They believe that giving every child a voucher worth a fixed amount to be used at any school would force bad schools to shape up. I think it would drain away from bad schools most of the resources necessary for shaping up. It would swamp good schools with applicants, so they could pick out the best students. It would subsidize rich families who already send their kids to expensive private schools, and it would encourage intolerance as parents pick schools that accept only “Their Kind.” The poorest families would be left to bestow minimal-value vouchers on the poorest schools. For them, there would be no choice.

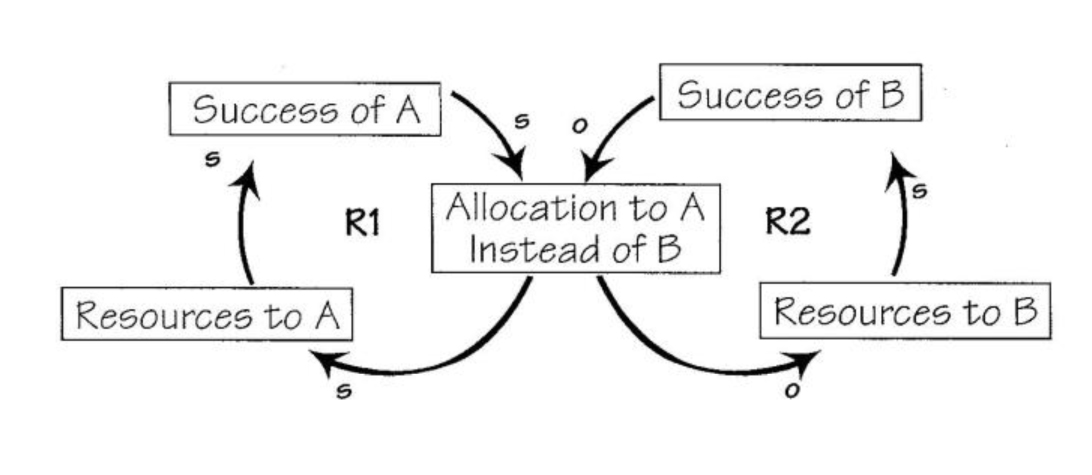

This kind of school system would set up a vicious circle that systems thinkers call “Success to t because the Successful.”

Such a system inefficiencies and injustices not because people are bad, but because people are smart enough to see that altruism is fatal in this game.

If you’ve played Monopoly'”, you’ve experienced “Success to is fatal in the Successful.” Everyone starts out equal. By chance, some players land on and buy up valuable properties for which they can charge rent. They use the rent money to build hotels, with which they can extract even more rent. The game is supposed to end when one person has bankrupted everyone else, but most adults quit long before that point has , been reached. The game gets too predictable and boring when the “hotels to the hotel-owners” stage kicks in.

Once our neighborhood offered a $100 reward for the most impressive display of Christmas lights. The winning family the first year spent the prize money on more lights. After they had won three years in a row, the contest was suspended.

“Success to the Successful” is no fun.

To him that hath shall it be given: lower electric rates for big users than for small ones; lower postage rates for bulk mailers than ordinary folks; and lower taxes on capital gains than on earned income. Incinerators, dumps, and polluting factories located disproportionately in low-income neighborhoods. The poorest kids get the worst healthcare and the worst schools.

“Success to the Successful” is not fair, though the successful work had to believe that they deserve the favors the system accords them.

Bill Gates’s Windows software dominates the superior Macintosh system because Microsoft and IBM have more marketing muscle than Apple. Big companies can afford more advertising, investment, researchers, accountants, lawyers. They can lean on distributors, suppliers, workers, communities, politicians. The politicians create a system in which no one can run for office without being rich or courting the rich.

“Success to the Successful” can destroy both market competition and democracy.

The problem is the structure of the system, not the morals of the people in it. “Success to the Successful” rewards the winner of a competition with the means to win again. It is especially perverse if it also penalizes losers. Such a system produces inefficiencies and injustices not because people are bad, but because people are smart enough to see that altruism is fatal in this game. It only takes parents who want the best for their children to ensure that other people’s children will be Monopoly losers for life, always paying rent, never collecting it, never seeing the board cleared or the opportunities opened, until things get so predictable, hopeless and degrading that they either drop out of the game or kick over the board.

To avoid such explosions and to keep games interesting, the world of sports has hundreds of devices for interrupting the “Success to the Successful” cycle and leveling the playing field: handicaps for weaker players; switching sides so the wind doesn’t always blow against you and the sun isn’t always in your eyes; loser chooses; starting new games with the score even.

Societies also have ways to break the cycle. Private property and democracy were invented to escape the terrible “Success to the Successful” traps of feudalism and monarchy. In modern times, we have come up with such leveling devices as progressive income taxes, inheritance taxes, anti-trust laws, securities trading laws, social safety nets, competence testing for jobs, affirmative action, and, the best invention of the lot, high-quality universal public education.

Our public school system has been one of the center posts of democracy and fairness in America. It was never as equitable as it should have been, but at least we honored it in concept and worked at it in practice. We had a shared commitment to each other’s children.

Now something has snapped. “Success to the Successful” is hailed as high wisdom. We refuse to pay for the education of other people’s children. Parents must choose between the best education for their own children right now and a future in which all children will grow up well educated.

That’s a choice no one should have to make.

Donella Meadows is a system dynamicist and an adjunct professor of environmental studies at Dartmouth College. She Is a MacArthur Fellow, and co-author of two best-selling books (the Limits to Growth and Beyond the Limits). She writes a weekly column for the Plainfield, NH Valley News.

”Success to the Successful Template”

The “Success to the Successful” structure suggests that if one person or group (A) Is given more resources, it has a higher likelihood of succeeding than B (assuming they are equally capable). As initial success justifies giving it more resources than B (loop R1). As B receives fewer resources. Its success diminishes further justifying more resource allocation to A (loop R2).