When Marvin T. Runyon took over the US Postal Service in 1992… He announced plans to slash layers of management and an early retirement program designed to trim the 700,000-strong workforce. The ambitious goals: Improve customer service, wipe out the Post Office’s deficit, and keep rate hikes below the inflation rate. Now, to help pay the bills, Runyon proposes raising the price of a first-class stamp from $.29 to $.32—and overall postage rates by 10.3%… When Runyon gives his annual report to Congress in late March, he will have to face an embarrassing fact: Postal Service employment has actually grown. And the service’s deficit… could top $2 billion.” (“The Check’s Still Not in the Mail,” Business Week, March 28, 1994).

• • •

The Postal Service has long been plagued by budget deficits and rate increases. In 1990, the year of the last postage increase, Postmaster General Anthony Frank faced soaring labor costs that fueled a growing budget deficit. His solution was to increase automation. When that failed to case the deficit, he pushed through the 29-cent postage stamp.

In 1994, current Postmaster General Marvin T. Runyon is once again faced with a growing deficit, due largely to a payroll that consumes 80% of the budget. His plan: introduce an early retirement package to trim the staff and allow the Post Office to benefit from the previous investments in computerization and automation. However, if history repeats itself, U.S. citizens will again ante up for a first-class rate increase.

The Post Office’s ongoing woes can be characterized as a “Fixes that Fail” situation, in which a problem symptom demands immediate resolution. A quick solution is implemented, which alleviates the symptom in the short term, but the unintended consequences of the “fix” only magnify the problem’s severity in the long term. Over a period of time, the problem symptom returns, often more dramatically than before.

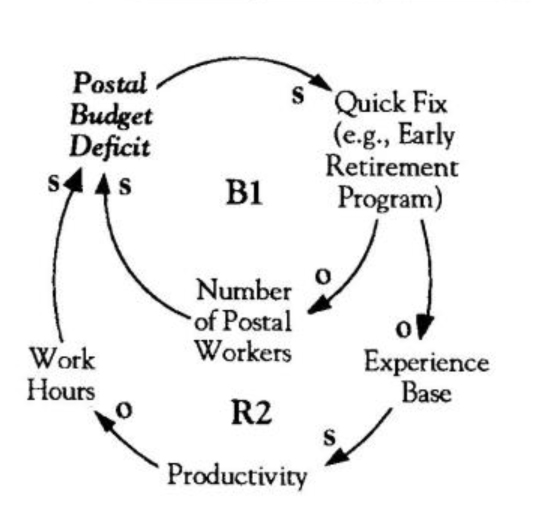

In the Post Office, the problem symptom is a recurring budget deficit. Although the Postal Service is required by law to break even, and usually does for about three years after each rate increase, rising costs—particularly work-force costs–eventually drag it back into the red. Runyon’s suggested fix was an early retirement program he hoped would shave 30,000 employees off of the Post Office payroll and ease the budget deficit (loop B1 in “USPS ‘Fixes That Fail’ “). Although the program was available to all employees who met certain seniority requirements, it was targeted toward supervisors who did not work directly with the mail.

Instead of attracting the targeted audience, approximately half of the 47,000 workers who opted to leave were letter carriers and clerks who were necessary for day-to-day operations. The retirement program thus cost the Post Office essential, experienced workers, who were replaced by workers requiring training and skill development. Overall productivity dropped, necessitating an increase in hours worked, which further exacerbated the deficit problem (R2).

The fallback plan to counter the growing deficit is to raise the price of first-class mail. Instituting rate increases is a strategy that the Post Office has used often, when other cost-cutting measures have failed. However, the increase in revenues from new postage rates may only obscure the need to trim the workforce or to implement more fundamental cost-cutting measures (another short-term “fix”).

USPS “Fixes That Fail”

To combat its deficit, the Post Office instituted an early retirement program to reduce the workforce and payroll (B1). However, many essential workers left, causing less experienced replacements to work longer hours to maintain service standards (R2).

The recent efforts toward workforce reduction may indicate that there is a move in the direction of cost-cutting rather than a complete reliance on rate increases. However, the ability to cut personnel is influenced by the postal unions and their allies in Congress. In addition, if efforts to reduce the workforce and to increase automation fail—and subsequent rate increases outpace inflation—they could continue to drive customers away. Fewer customers mean less revenue to cover the same expenses, leading to another rate hike. This spiral could result in “rates so high that, with-out regulations limiting postal competition, no one would use the USPS” (see “U.S. Postal Service: Are Rate Hikes Paying Off?” Oct. 1990).

If the Post Office is to compete with fax machines, overnight carriers, and specialized courier services, the unions and the Postal Service need to join together to create a more efficient, cost-effective mail system. Creating a vision that all parties can believe in may be a starting point for a better working system. Otherwise, the Post Office could face new problems, in the form of pressure to allow competitors into the first-class mail market.