Stress management — long the domain of psychiatrists and therapists — is increasingly being recognized by corporate America as a critical workforce issue. The reason is partly financial. Stress directly affects the bottom line — in lower productivity, lost time due to sick days, turnover, higher defect rates, higher medical costs, and more. “It has been estimated that output could be boosted by at least 10 percent if the work loss and impaired job performance attributable to mismanaged stress were eliminated,” notes Jack Homer, a system dynamicist and management consultant who has studied worker burnout. And, according to Fortune magazine, stress-related illnesses cost twice as much as other workplace injuries: more than $15,000 in medical treatment and lost time.

Though there is much agreement today that stress is a problem, there is little accord on what causes it or how to address it. How can workers and managers deal effectively with the rising stress level in organizations? Will the current batch of remedies be effective over the long term? Is stress just a natural part of organizational life, or are there leverage points for changing the structure of the workplace in order to reduce or eliminate the sources of stress? Beneath all these issues lie deeper questions about what we value as individuals, organizations, and as a society.

Stress Management 101

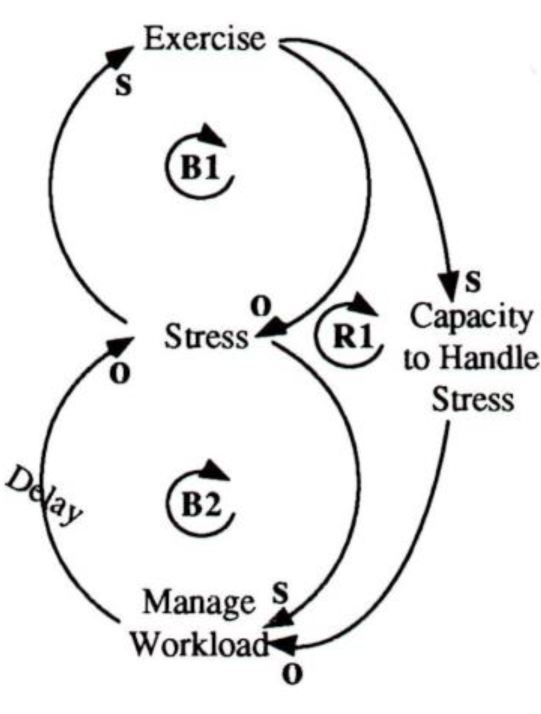

One working definition of stress is “when you begin every day with 30 hours worth of ‘stuff’ to finish by the end of a 24 hour day.” Some symptoms of stress you can feel immediately — shortness of breath or stomach cramps — which cry out for immediate action. Other symptoms — ulcers, hypertension, sleep disorders — develop over a long period of time. One popular remedy for feeling “stressed-out” is to exercise (see “Shifting the Burden of Stress Management” diagram). As you exercise, you relieve tensions in your body and begin to feel less stressed (B1). Another, more fundamental response to stress is to learn how to better manage your workload. As you increase your ability to manage your workload, the stress will decrease (B2). But it takes time before the payoff appears. And since exercise programs relieve stress relatively quickly, the impetus for managing the workload disappears, making workload reduction seem unnecessary.

Shifting the Burden of Stress Management

Although the exercise loop (or other coping loops) are effective in relieving the symptoms of stress, the perverse side effect is that they also increase your capacity to handle more stress. Those 30 hours worth of work seem less intimidating if you are pumped up and full of energy. But eventually, the stress level will climb along with the growing workload, reinforcing your need for more exercise (RI). If twice a week is not enough, make it five. If needed, go on weekends. Have a knot in your stomach? Take some stress tablets. Feeling a bit edgy and anxious? Sign up for a gymnastics class. Suffering from malaise and lethargy? Enroll in a stress management workshop. There is an endless supply of quick fixes available. Each will help in the short term, but to the extent that they only increase our ability to handle more stress, they just reinforce the problem. Intimately, this prolonged dynamic contributes to burnout (See “Burnout” sidebar).

The Delegation Shuffle

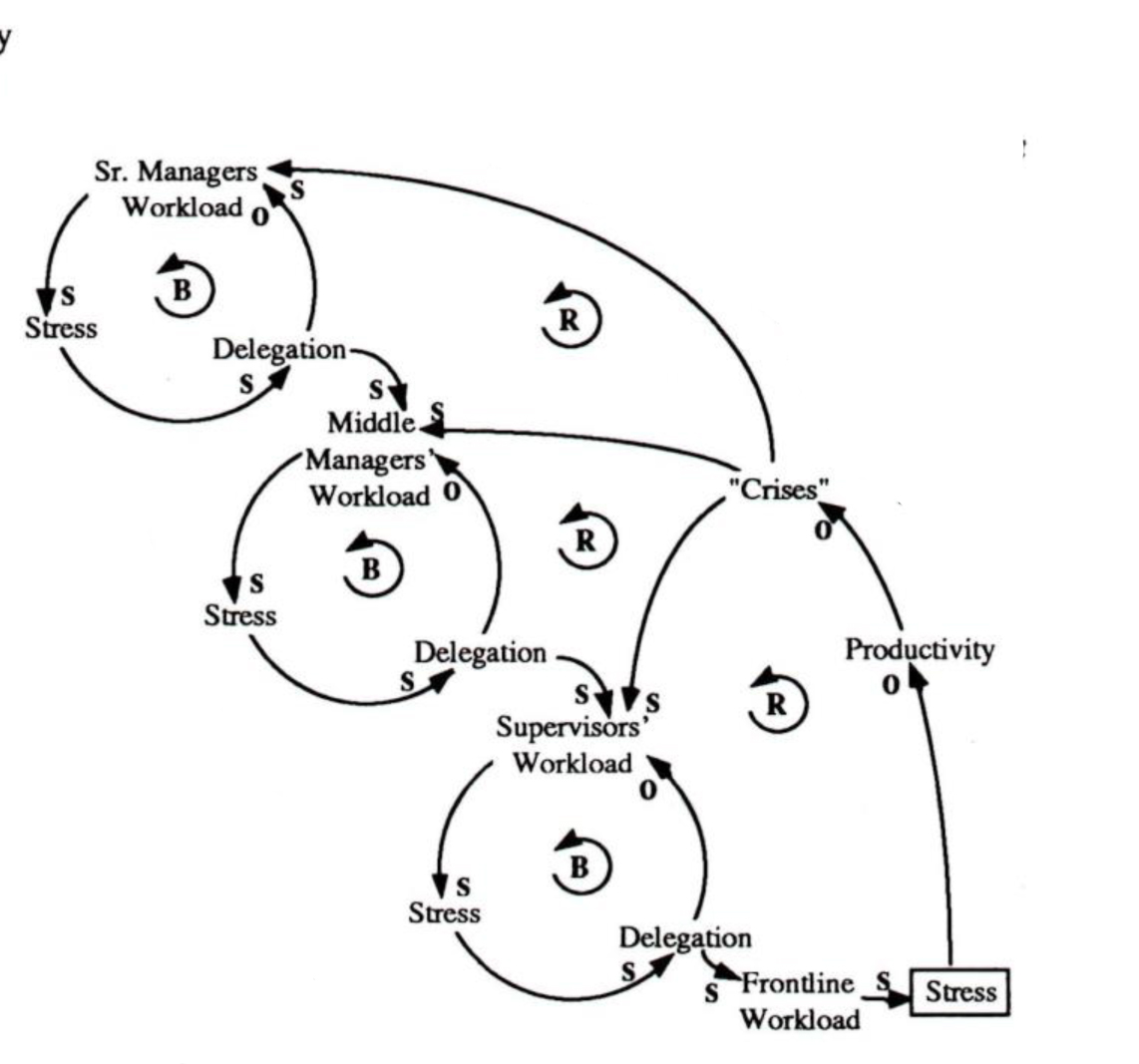

If we are serious about tackling stress by reducing our workload, the obvious solution seems to be to delegate more. The problem with delegating, however, is that it does nothing to reduce the overall workload of a department or division — it simply shifts the work burden onto another person (see “The Delegation Shuffle” diagram) As each person finds himself overwhelmed by the workload, he delegates more responsibilities to the next level. That raises the workload of the person at the next level until she becomes overworked and begins to delegate work to someone else. The flow of work trickles down, leaving each person working at maximum capacity — and usually burying the front line worker.

Burnout

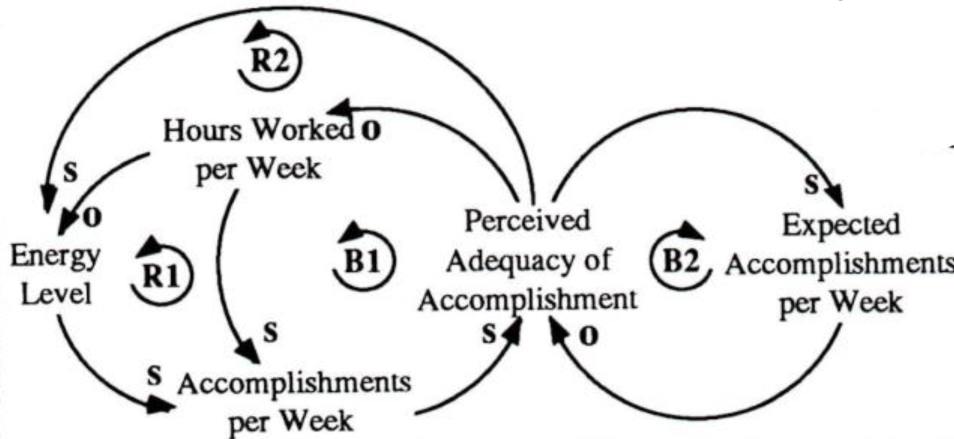

Perhaps the most well-known manifestation of stress in the workplace is “burnout,” the total mental and physical exhaustion that comes from overwork. Burnout results from an individual’s continual attempts to fulfill unmet expectations by working longer hours. Longer hours, however, mean more exposure to the normal stress of work, which drains the individual’s store of energy and leaves less time to replenish that energy. Over time, this energy drain may render the individual less capable of reaching her goals, leading her to work even longer hours to try to “catch up.” The result is a vicious cycle of unfu011ed expectations, overwork, and eventual burnout (R1 and R2).

Perhaps the most well-known manifestation of stress in the workplace is “burnout,” the total mental and physical exhaustion that comes from overwork. Burnout results from an individual’s continual attempts to fulfill unmet expectations by working longer hours. Longer hours, however, mean more exposure to the normal stress of work, which drains the individual’s store of energy and leaves less time to replenish that energy. Over time, this energy drain may render the individual less capable of reaching her goals, leading her to work even longer hours to try to “catch up.” The result is a vicious cycle of unfu011ed expectations, overwork, and eventual burnout (R1 and R2).

Given the structure of the burnout cycle, prevention appears to be simple: lower our expectations and reduce the workload (B2). But that is not enough, says Homer. Once an individual reduces his workload to a reasonable level, his modest expectations and rising energy enable him to finish work at a satisfying rate without putting in a lot of hours. This euphoric period of “coasting” is short-lived, however. Why? Because such satisfaction is unnatural for R2 workaholics (or those in workaholic environments) and only encourages Perceived Expected them to 8 Adequacy of B2 expand their Accomplishment per Week goals and begin the cycle again.

If the tasks are not delegated with a clear purpose and understanding of the skills needed, individuals may find themselves assigned to tasks that they are not ready to handle. This increases their stress and their workload, forcing them to shift even more responsibilities downstream. As more people are called on to do tasks they are not prepared for, the number of mistakes and crises rises, productivity decreases, and the stress level increases throughout the system. The result is that the stress that was shifted out of the system feeds back in on itself, creating a vicious cycle of increasing stress.

Toward Stress Prevention

One of the problems with the way stress has traditionally been handled in corporations is that it has been treated as an individual problem. Companies offer employees stress management programs, relaxation classes, and other methods for dealing with stress. But these programs are symptomatic solutions at best. By providing and endorsing such programs, companies are teaching employees how to “cover up” underlying stress and sending an unspoken message to individuals that they are to blame for the stress they feel.

Stress management programs rarely address the organizational sources of stress. “How can it possibly make sense for a company to soothe employees with one hand — teaching them relaxation through rhythmic breathing — while whipping them like egg whites with the other, moving up deadlines, increasing overtime, or withholding information about job security?” asks Fortune magazine. And Jack Homer points out that frustration is at the heart of burnout: frustration from unclear roles and responsibilities, a poor job fit, inadequate rewards and employee support, or deadline pressure.

The key question for dealing with stress on an organizational level is: how do we as an organization create environments which are either stressful or stress-free? To answer this question, we need to look at how organizational structures are contributing to the very stress we are trying to eliminate. For example, if the reward systems are set up with the single-minded goal of maximizing quarterly results, the result could be rising stress levels and more incidences of burnout throughout the organization, which can end up actually reducing overall productivity.

Sometimes the corporate culture is the culprit. In The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge tells the story of a friend who fruitlessly tried to reduce burnout among professionals in his rapidly growing training business: “He wrote memos, shortened working hours, even closed and locked offices earlier — all attempts to get people to stop overworking. But all these actions were offset — people ignored the memos, disobeyed the shortened hours, and took their work home with them when the offices were locked. Why? Because an unwritten norm in the organization stated that the real heroes, the people who really cared and who got ahead in the organization, worked seventy hours a week — a norm that my friend had established himself by his own prodigious energy and long hours.”

This story illustrates an important lesson for developing effective organizational responses to stress: no stress reduction program will be effective if the organizational norms, systems, and culture do not support that goal. Creating a long-term strategy for dealing effectively with stress will mean rethinking some of our traditional ways of thinking about and dealing with stress.

Lessons from the Army

Surprisingly, some effective techniques for creating built-in mechanisms to reduce stress in organizations come from the army. According to Fortune magazine, “The number one psychological discovery from World War II is the strength imparted by the small, primary work group.” Having stable work groups becomes even more important when a company is undergoing a major upheaval such as a downsizing. A tightly-knit work group can help lend cohesion and continuity to an otherwise uncertain workplace. In addition, army research also found that keeping a work group together after a battle (or a downsizing) is crucial, too, “since members, by collectively reliving their experience and trying to put it in perspective, get emotions off their chests that otherwise might leave them stressed out for months or years.”

Another effective method for reducing stress throughout the workplace Workload is institutionalizing methods for taking time off, to help employees maintain a balanced Stress perspective and stable energy level. The five-day workweek with weekends off is one formalized structure for building in stress-relief valves. So are holidays and vacation days. Prolonged periods of working longer hours and on weekends, however, often “short-circuit” such safety measures.

“Time Outs”

Institutionalized “time outs” could go even further. In the U.S., vacation days (and time off in general) are viewed as lost production time, and thus an added cost. Given this mental model, it is not surprising that in a recent report, the U.S. was ranked at the bottom of a list of industrialized countries on the average number of vacation days per year. The U.S. (along with the Japanese) had 10 vacation days versus 20-30 days for several European countries.

If time off was viewed more as an investment than a cost, vacations could be seen by corporations as an important ally for keeping their employees productive and stress-free. Manufacturers know that investments in maintenance programs and planned down times for their equipment pay off in fewer breakdowns and longer useful lifes. Are we guilty of treating our machines and physical plants better than our employees simply because it is easier to measure the effects of overwork on machines than on people?

The Delegation Shuffle

Ultimately, stress management comes down to making some fundamental decisions about what we value — as both companies and individuals. As individuals, do we see our work as consistent with our goals and our other roles — as parents, community leaders or church leaders? As companies, how do we view our role in society — as employers of resources, producers of goods, suppliers of services, enhancers of human potential, or vehicles for social progress? Do we value our employees and see them as whole individuals — with families, concerns and experiences that affect and are affected by their work? Answering these questions will provide a starting place for addressing the issue of stress at a fundamental, not symptomatic, level. The portions of this article on burnout were adapted from Jack Homer’s article, “Worker Burnout: A Dynamic Model with Implications for Prevention and Control” which appeared in the summer 1985 issue of the System Dynamics Review.