In this issue we return to our coverage of systems archetypes — dynamic structures that are found repeatedly in diverse settings. In future issues, we will alternate between archetypes and other tools in the systems thinker’s toolbox.

Do you recall any hot summer days when you and your family decided to spend a relaxing day at the local swimming pool? You loaded up the car and arrived at the pool only to discover that every other family had the same idea. So instead of the relaxing outing each family anticipated, everyone ended up spending a nerve-wracking day dodging running children and trying to cool off in a pool filled with wall-to-wall people. In many similar situations, people hoping to maximize individual gain end up diminishing the benefits for everyone involved. What was a great idea for each person or family becomes a collective nightmare for them all.

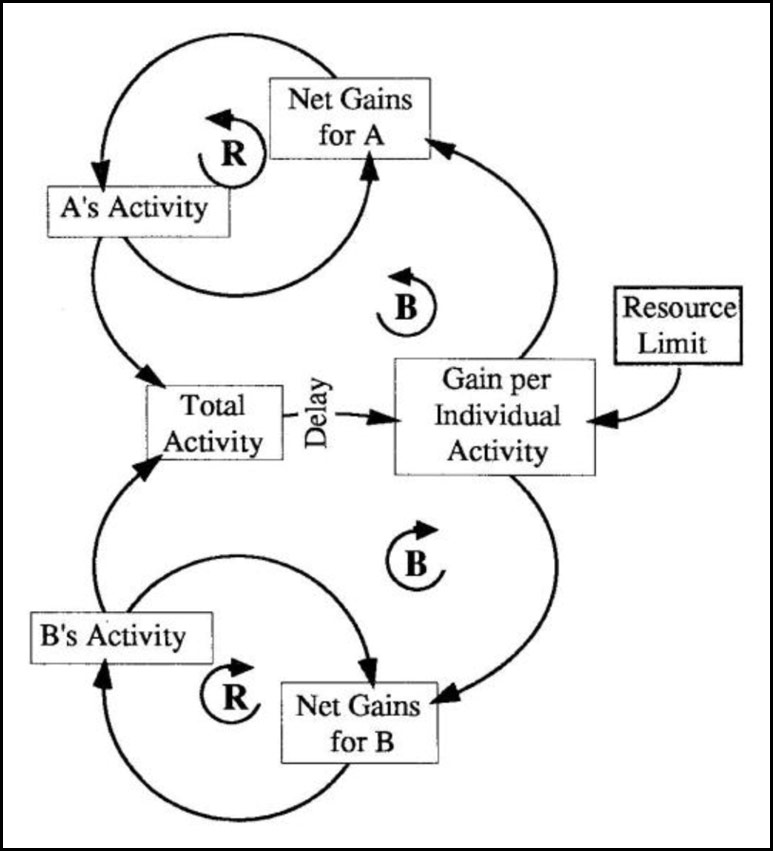

Tragedy of the Commons Template

In a “Tragedy of the Commons” structure, each person pursues actions which are individually beneficial (R), but eventually result in a worse situation for everyone (B).

Individual Gain, Collective Pain

At the heart of the “Tragedy of the Commons” structure lies a set of reinforcing actions that make sense for each individual player to pursue (see “Tragedy of the Commons Template”). As each person continues his individual action, he gains some benefit. For example, each family heading to the pool will enjoy cooling off in the swimming area. If the activity involves a small number of people relative to the amount of “commons” (or pool space) available, each individual will continue to garner some benefit. However, if the amount of activity grows too large for the system to support, the commons becomes overloaded and everyone experiences diminishing benefits.

Traffic jams in L.A. are a classic example of how a “public” good gets overused and lessened in value for everyone. Each individual wishing to get quickly to work and back uses the freeway because it is the most direct route. In the beginning, each additional person on the highway does not slow down traffic because there is enough “slack” in the system to absorb the extra users. At some critical level, however, each additional driver brings about a decrease in the average speed. Eventually, there are so many drivers that traffic crawls at a snail’s pace. Each person seeking to minimize driving time has in fact conspired to guarantee a long drive for everyone.

This structure also occurs in corporate settings all too frequently. A company with a centralized salesforce, for example, will suffer from the “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype as each autonomous division requests that more and more efforts be expended on its behalf. The division A people know that if they request “high priority” from the central sales support they will get a speedy response, so they label more and more of their requests as high priority. Division B, C, D, and E all have the same idea. The net result is that the central sales staff grows increasingly burdened by all the field requests and the net gains for each division are greatly diminished. The same story can be told about centralized engineering, training, maintenance, etc. In each case, either an implicit or explicit limit is keeping the resource constrained at a specific level, or the resource cannot be added fast enough to keep up with the demands.

Brazil’s Inflation Game

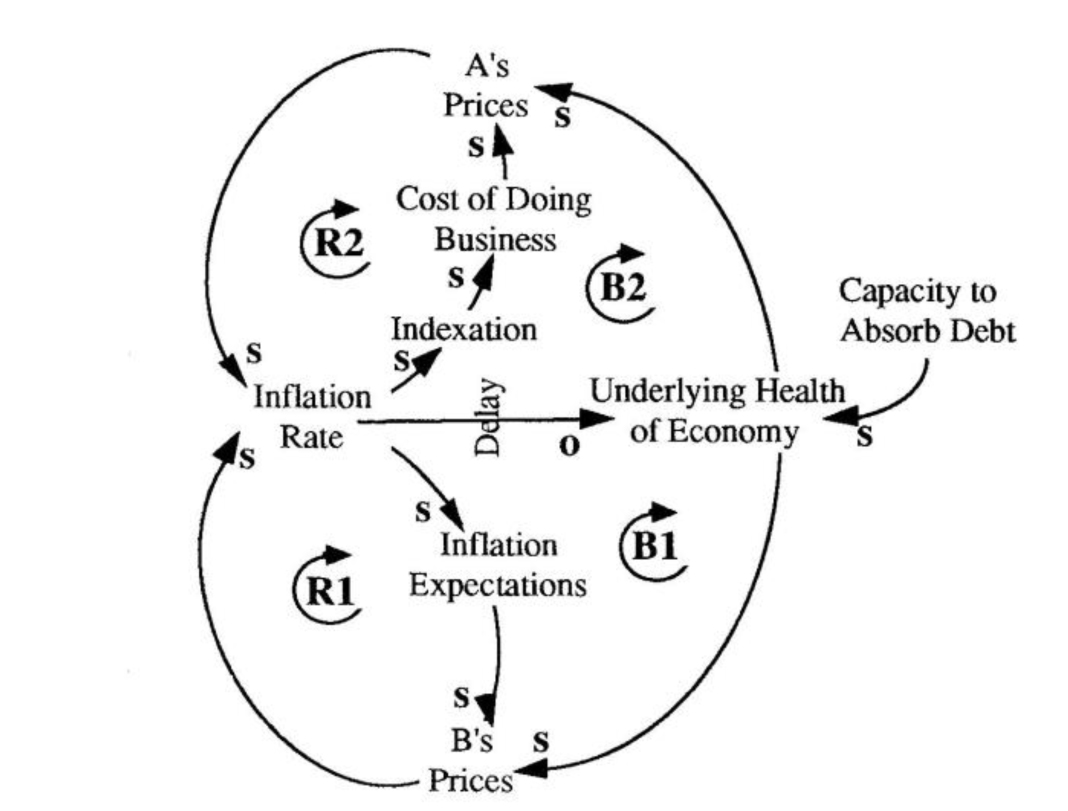

When the shared commons is a small, localized resource, the consequences of a “Tragedy of the Commons” scenario are more easily contained. At a national level, however, the “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype can wreak havoc on whole economies. Take inflation in Brazil, for example. Their inflation was 367% in 1987, 933% in 1988, 1,764% in 1989, and 1,794% in 1990. With prices rising so rapidly, each seller expects inflation to continue, therefore seller B will raise his price to keep up with current inflation and hedge against future inflation (see “Brazil’s Inflation Tragedy”). With thousands of seller B’s doing the same thing, inflation in-creases and reinforces expectations of continued inflation, leading to another round of price increases (R1).

Inflation also leads to indexation of wages, which increases the cost of doing business. In response to rising business costs, Seller A raises her price, which fuels further inflation (R2). Since there are thousands of Seller A’s doing the same thing, their collective action creates runaway inflation. The underlying health of the economy steadily weakens as the government and businesses perpetuate endless cycles of deficit spending to keep up with escalating costs. Over time, everyone grows increasingly preoccupied with using price increases to make profits rather than investing in ways to be more productive. Eventually the economy may collapse due to high debts and loss of global competitiveness, resulting in dramatic price adjustments (B1 & B2).

Brazil's Inflation “Tragedy”

Common “Commons”

Perhaps the trickiest part of identifying a “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype at work is coming to some agreement on exactly what is the commons that is being overburdened. If no one sees how his or her individual action will eventually reduce everyone’s benefits, the level of debate is likely to revolve around why individual A should stop doing what he is doing and why individual B is entitled to do what she is doing. Debates at that level are rarely productive because effective solutions for a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation never lie at the individual level.

In the sales force situation, for example, as long as each division defines the commons to include only its performance, there is little motivation for anyone to address the real issue — that the collective, not individual, action of each division vying for more sales support is at the heart of the problem. Only when there is general agreement that managing the commons requires coordinating everyone’s actions can issues of resource allocation be settled equitably.

Managing the Commons

Identifying the commons is just the beginning. Other questions that help define the problem and identify effective actions include: What are the incentives for individuals to persist in their actions? Who, if anybody, controls the incentives? What is the time frame in which individuals reap the benefits of their actions? What is the time frame in which the collective actions result in losses for everyone? Can the long term collective loss be made more real, more present? What are the limits of the resource? Can it be replenished or replaced?

The leverage in dealing with a “Tragedy of the Commons” scenario involves reconciling short-term individual rewards with long-term cumulative consequences. Evaluating the current reward system may highlight ways in which incentives can be designed so that coordination among the various parties will be both in their individual interest as well as the collective interest of all involved. Since the time frame of the commons “collapse” is much longer than the time frame for individual gains, it is important that interventions are structured so that current actions will contribute to long-term solutions.

For further reading about this archetype, see The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (Doubleday, 1990), by Peter M. Senge.