Organizational life is awash with incongruities. In one organization the CEO told the world, “Product X is our top priority,” even as the development group was putting it on the back burner. In another company, the unit that tracked product costs didn’t communicate with the unit that set prices — although such costs are crucial for making good pricing decisions. In a third, a manager announced an open office arrangement to “improve communication.” It was the first time the staff had heard of the idea.

In situations like these, the players are usually acting rationally from within their local perspectives — despite appearances to the contrary. Unfortunately, their reasoning is often not clear to others. Therefore, observers invent explanations such as “all he cares about is the stock price,” “he’s a typical sales guy,” and “she’s just trying to please the boss.” These assumptions cannot be stated openly, but they influence how people act. Patterns then become established in which players unwittingly conspire to create behavior that is not in the best interest of the whole organization.

One reason these patterns persist is that individuals may not understand the effects of their behavior on the whole. And even when individuals do understand the whole, they may believe that they cannot act differently. A plant manager in the midst of a divisional downsizing program, for example, agreed that success would require redesigning work across several plants, not just within each plant. But he believed upper management would see organization-wide redesign as a delay tactic on his part to put off making cuts in his own plant. Therefore he continued to go along with a downsizing strategy that he believed was unwise.

To create organizations that learn, members must develop a shared understanding of how local rationalities interact to create organizational incongruities. Insight into each other’s perspective reduces the escalation of private explanations that so often reinforce counterproductive patterns. It then becomes possible to see how one’s own actions contribute to the problem — and to design solutions jointly that no one could implement alone.

Covert Budgeting

To further understand how these dynamics play out in corporations, consider a case of covert budgeting. The CEO of a large manufacturing company wished to reward individual initiative by connecting pay increases to performance. He was asked, “What if everyone in our department performs exceptionally well? Can we all get a large increase? Or will an individual receive more by being the one good performer in a department in which everyone else performs poorly?” The CEO responded that everyone should be treated as an individual. If every individual in a department — or in the company as a whole — performed exceptionally well, then everyone could get a large increase. Conversely, if no one performed exceptionally well, no one would get a large increase. Performance would therefore be the key.

This policy created difficulties for managers as they did their budgeting and salary planning, because the company tracked both how its compensation structure matched that of its competitors, and also how far each division was above or below a target compensation level. If a division was above its target, managers experienced pressure to hold the line on salary increases. And if the wage bill for the company as a whole increased too quickly, financial performance would, of course, suffer. Therefore, each year senior management calculated what was a reasonable increase in the total wage bill and based employee compensation on that figure. Although the practice made sense, it was in direct conflict with the policy of rewarding individual performance independently of how others performed and were rewarded.

In this situation, each year first level managers were asked to figure what salary increases they would recommend for each of their employees. These numbers were sent to second level managers who added recommended increases for their subordinates and passed the results to third-level managers, and so on up the line. More often than not, when the results arrived at division management, the wage increases added up to more than could be allowed, so the numbers were sent back down for further work. Some years the yo-yo went through two or three cycles.

It did not take long for managers to realize that senior management had a particular wage target in mind (say a 5% increase). But managers were not told in advance what the number was that year. To tell managers a target number would let them duck responsibility for deciding what their people deserved, based on their performance. Not telling, of course, led to the considerable cost in managerial time of reworking the compensation numbers.

Managers knew there was a covert compensation budget, tried to second-guess what it was, and in fact did duck responsibility for compensation decisions by deferring to the budget. This came out when the CEO met with employees and asked, “What does your manager tell you when you do not get a pay increase?”

“Oh,” was the reply, “he tells me the money isn’t in the budget.” “But there isn’t any budget for pay increases!” the CEO responded. Of course, on a de facto basis, there was a budget. But it is possible that the CEO did not know.

This case illustrates a central paradox of organizational learning: good members, acting rationally within the organizational world they know, create and maintain defensive routines that prevent the organization from learning. Defensive routines are habitual ways of interacting that serve to protect us or others from threat or embarrassment, but also prevent us from learning. Once they are started, these routines seem to take on a life of their own. Each player experiences them as an external force, imposed by the situation and by other actors. But they can actually be changed only by the players themselves. And change becomes likely only when players develop shared understanding of the interlocking dilemmas that lead them to act as they do (see “What Are Defensive Routines?”).

Defensive Routines

Defensive routines have probably existed for as long as there have been organizations. However, they take on an increasing importance in today’s world for several reasons.

First, the pace of change in business today has put a premium on an organization’s ability to learn. Therefore, routines that inhibit learning can no longer be tolerated.

WHAT ARE DEFENSIVE ROUTINES?

Defensive routines are actions that…

- Prevent individuals and organizational units from experiencing embarrassment or threat.

- Simultaneously prevent people from identifying and changing the causes of the embarrassment or threat.

- Are taken for granted as “the ways things work.”

Second, organizations must be able to integrate an increasing diversity of perspectives. Cultural, gender, and ethnic differences are but some of the drivers of diversity in how people think. Members of different professions, different functions, and different points in a supplier-customer chain can make unique contributions to shared understanding. However, defensive routines prevent us from taking advantage of multiple perspectives.

Third, organizations are being designed to rely more on lateral and less on hierarchical links. Ironically, although command-and-control organizations may spawn defensive routines, they may also be able to function at an acceptable level despite them. It is when individuals must span lateral boundaries for the organization to function that it becomes essential to reduce routines that prevent mutual influence and learning.

Characteristics of Defensive Routines

Defensive routines arise from a combination of behaviors and structures that interact to produce counterproductive and often alienating situations. We have accurate understanding only of our own circumstances; as a result, we are often unaware of how our actions affect others and how our behavior is part of a larger system. In this respect, defensive routines are like other systems that we find unmanageable; we only see small pieces of the puzzle and fail to realize how our well-intended actions create and maintain counterproductive patterns of behavior.

Because we cannot fully understand other people’s positions, we often explain their behavior by attributing intentions that are based on our own assumptions. This human tendency becomes problematic when we focus on the difficulty that someone’s behavior is creating for us and then go through a tacit chain of reasoning: They know they are having this impact… they intend it… it must be because they ______ (don’t care, are protecting their turf, etc.). This logic makes it reasonable to hold others responsible for the problem.

Having made such attributions, we often try to conceal them. For example, if I believe that Jane is making a lame excuse to get out of meeting with me, I probably would not say that to her because it might create an argument. But this means that the attributions I make about Jane remain untested. Perhaps I decide that Jane is not interested in my work, so I do not invite her to the next meeting. Later Jane hears what I am doing and offers suggestions. But my project is so far along that using her ideas would require throwing out much of what I have done. “She wants influence,” I think, “but she doesn’t want to take the time. She’s impossible.” As we get more frustrated, angry, or discouraged in such situations, our untested attributions about others often begin to escalate.

On those rare occasions when routines are challenged, attributions and emotions are often expressed at an explosive level and the resulting discussion is counterproductive. These experiences confirm people’s belief that it is best not to discuss the routines. As a result, defensive routines become undiscussable open secrets — and people begin to take their existence for granted. “Getting things done around here” begins to mean acting in ways that leave the routines in place.

If, for example, the executive committee has difficulty discussing conflictual issues, the CEO may choose to move those issues to a series of one-on-one meetings. While bypassing defensive routines may be necessary for short-term progress, it often reinforces the routines for the longer term. With the conflictual issues safely off the agenda, the executive committee becomes even more incapable of dealing with the important business of the firm.

Using Action Maps to Unlock Defensive Routines

To reduce defensive routines, we need to recognize what maintains the routines. How people think as they design actions — making assumptions and attributing intentions to others, keeping their attributions private, and acting on the basis of that untested thinking — all contribute to defensive routines. We can actually think of defensive routines as systemic structures whose causal links are embedded in the mental models of the players.

REDUCING CHANGE ANXIETY

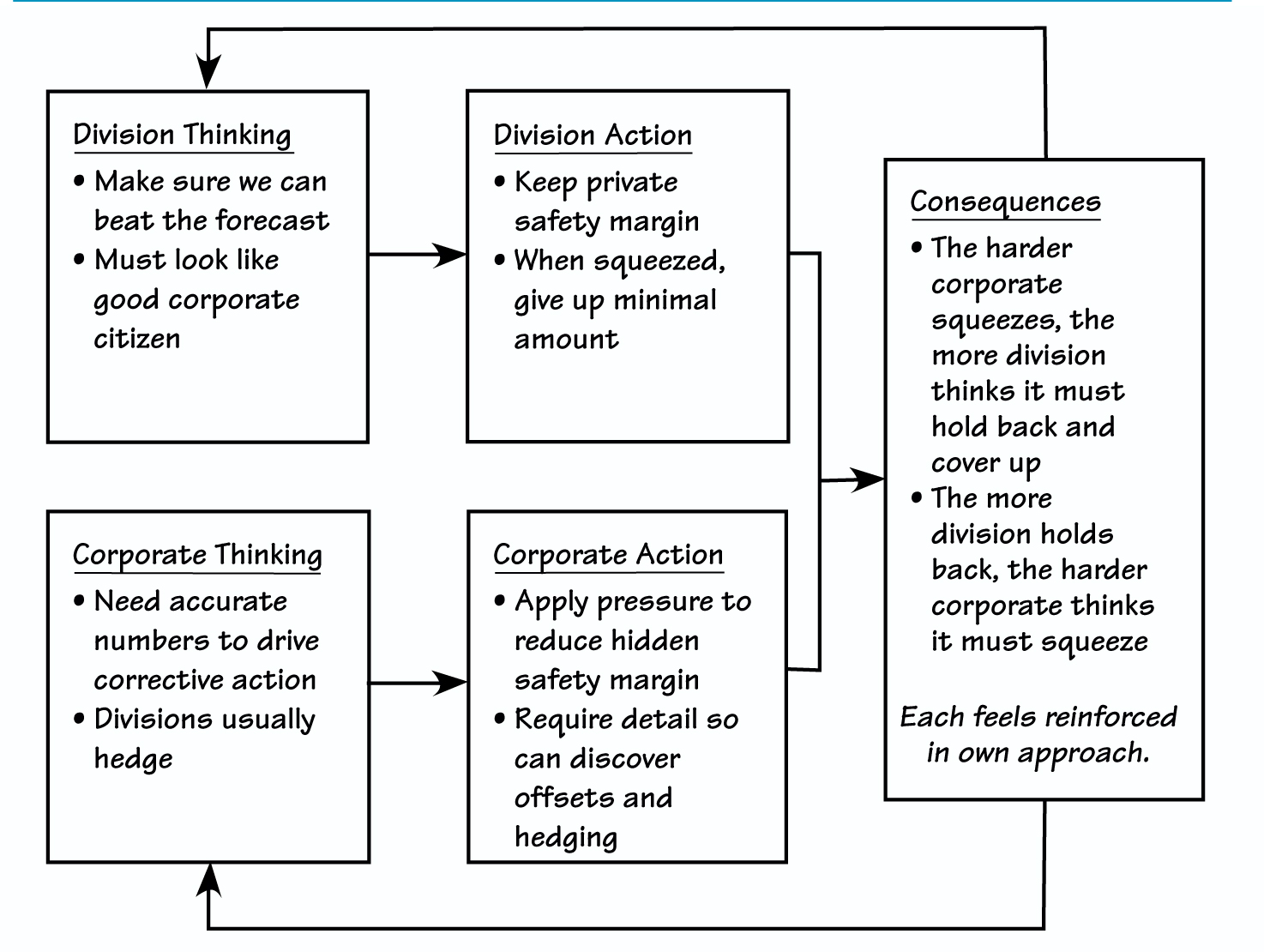

The “Forecasting Game Action Map” makes explicit the “local rationalities” that led to actions taken by both the division and corporate, and shows how the unintended consequences of those actions lock both players into a counterproductive dynamic.

Therefore we might try to reduce the grip those routines have by helping people reflect on the mental models that drive their actions. While this is an essential step, it is not usually the best place to start, since most people do not see a pressing need to change their mental models. Working on mental models makes sense only after it becomes clear that the work is necessary in order to make progress on organizational responsibilities.

A more effective approach to addressing defensive routines is to start by exploring key organizational objectives that members are having difficulty achieving. Individuals are asked to identify the barriers to achieving their objectives by describing examples and illustrating how they or others have tried to manage the barriers. This information becomes the basis for discussion in a group or management team.

One way to organize this information is in action maps that show how different players think and act in ways that unintentionally contribute to defensive routines. By displaying the interlocking dilemmas of each party and how their actions reinforce each other, the maps can counteract the tendency to polarize. Organizational dilemmas are most often managed by each group grabbing one horn. They pull in different directions, each seeing clearly that the other way lies disaster. But the essence of a dilemma is that either horn leads to trouble. Maps can actually help groups embrace the whole dilemma and work from there. They also puncture the undiscussability that maintains defensive routines. By identifying the contribution of each party to unintended results, maps reduce the tendency to pin blame rather than to work together.

The Forecasting Game Action Map

The “Forecasting Game Action Map” (see diagram) was designed to make the difficulties experienced by a management group visible and discussible. The group identified their forecasting process as a key barrier to making sound resource allocation decisions. While the map was based specifically on the information derived from that organization, individuals from several different organizations have since confirmed that it describes what happens in their worlds as well.

The “game” works this way. People in divisions wish to ensure that they will be able to make or beat their forecast. As forecasting is an inherently uncertain enterprise, to ensure beating the forecast it is necessary to leave a safety margin by overstating anticipated expenses or understating anticipated revenues (perhaps by using assumptions that are known to be conservative). These tactics, however, are inconsistent with the stated obligation to give corporate a forecast that is as accurate as possible, and therefore it must be kept private. If the division does not appear to be a good “corporate citizen,” corporate would have legitimate reason to impose sanctions. Therefore, the fact that there are safety margins and that they are being kept private must be hidden as well. How? By acting as if nothing is being hidden.

From corporate’s point of view, accurate information is essential for guiding management action. But corporate officers are not naive; they know divisions often hedge by keeping private safety margins. Therefore corporate officers apply pressure, telling divisions to rework the numbers to reduce costs or increase revenues, or they may pose sharp questions or require detailed information in an effort to discover where safety margins may be hidden.

When corporate squeezes, divisions know they must often “give” a little bit on their numbers. They try to give the minimal amount that will satisfy corporate while still leaving an adequate safety margin. Of course, the fact that divisions give something reinforces corporate’s efforts to squeeze (“See, they were able to do more than they had said”). On the other hand, the established pattern of “squeezing and giving” reinforces the need for divisions to create private safety margins: they must build in some extra cushion so they will be able to give when they are squeezed and yet still have something left over. Each side feels reinforced in its approach.

All of the players involved are familiar with the Forecasting Game; being presented with a map simply makes it legitimate to talk about the issues.

This pattern, or a variation on it, is an open secret in many organizations. Not only does it contaminate the forecasting process, but it also contributes to a culture of ritual deception. Yet most players within the “Game” are actually striving to act responsibly and do a good job. Many dislike participating in deception, but feel they have no choice. Others have become inured to the process or have created rationalizations to justify their actions. All of them are locked into a recurring pattern that will continue unless they jointly work to change it.

Discussing Action Maps

Discussing a map of one’s own defensive routines can be both a liberating and difficult experience. It can be liberating because most of us dislike living open secrets. All of the players involved are familiar with the Forecasting Game; being presented with a map simply makes it legitimate to talk about the issues. And it becomes possible to design change actions that were not possible as long as the situation could not be discussed. For example, players might agree on legitimate reasons for conservative forecasting. Divisions might make the reasoning underlying their forecasts more transparent to corporate, and corporate might allow some degree of hedging against uncertainty.

But talking about defensive routines can be difficult for all the reasons that they are usually kept undiscussable. Habits of thought persist that lead people to make attributions about others, to get upset about it, and to remain blind to the legitimacy of other perspectives. For example, administrators at the director level of a public agency were talking about the pressures that led them not to share as much budget information as staff wanted. An administrator one or two levels lower listened as long as he could and then burst out, “You’re all making excuses! I know you could share more information if you wanted to!” Comments like this can easily escalate into a polarized discussion that inhibits inquiry and reflection — and reinforces the very defensive routines that were being discussed.

Open discussion about defensive routines can improve mutual understanding and create shared commitment to reducing the routines. Implementing new actions, however, often requires developing the skill to act differently under stress. Telling an executive that he or she is contributing to defensive routines may be a tall order. It is at this point that it makes sense to introduce concepts and techniques for creating learning conversations. Once we understand how current, taken-for-granted ways of acting create defensive routines that prevent achieving organizational objectives, members may be ready to commit to practicing new ways of acting.

Robert Putnam is a partner in Action Design Associates, a consulting firm based in Newton, MA. He is co-author with Chris Argyris and Diana McLain Smith of Action Science (Jossey-Bass, 1985).