Have you ever wondered why clocks run in the…uh…clockwise direction? Or why the QWERTY keyboard design is the standard for virtually all English typewriters and keyboards? Are they really superior technologies, or merely the result of random selection? The answer to these questions lies in the “Success to the Successful” archetype.

In “Success to the Successful,” the demands made by competing groups for a common resource (time, money, people, attention, etc.) are linked by two reinforcing loops. Because of the nature of the relationship, giving more to one group means leis is available for the other. For example, if more of a limited budget is allocated to Department A, A becomes more successful, which justifies allocating more resources to further its success. At the same time, less is allocated to Department B; therefore B’s success drops, which justifies not allocating resources to B. Over time, the performance of both parties reflects the way the resources were allocated — one keeps improving and the other stalls or declines.

In many cases, although it might seem like a “survival of the fittest” strategy is at work, the “Success to the Successful” structure suggests that the final result may be due more to initial conditions than to intrinsic merits. In other words, rather than a survival of the fittest, it is more a survival of the first.

When clocks were first invented, for example, there were competing designs for the direction of rotation; what we now refer to as clockwise and counter-clockwise could easily have been the reverse. There was no mechanical advantage of one direction over the other; one simply achieved greater initial acceptance. The result is that today the other direction somehow seems wrong.

A “Success to the Successful” dynamic is often difficult to stop because of the momentum that occurs from the reinforcing success loop. Halting that process requires a concerted effort to challenge the assumptions or processes that created the dynamic. The following seven steps are designed to help you or your organization critically challenge your success loops by unlearning what you are already good at, so you can learn new approaches and alternatives.

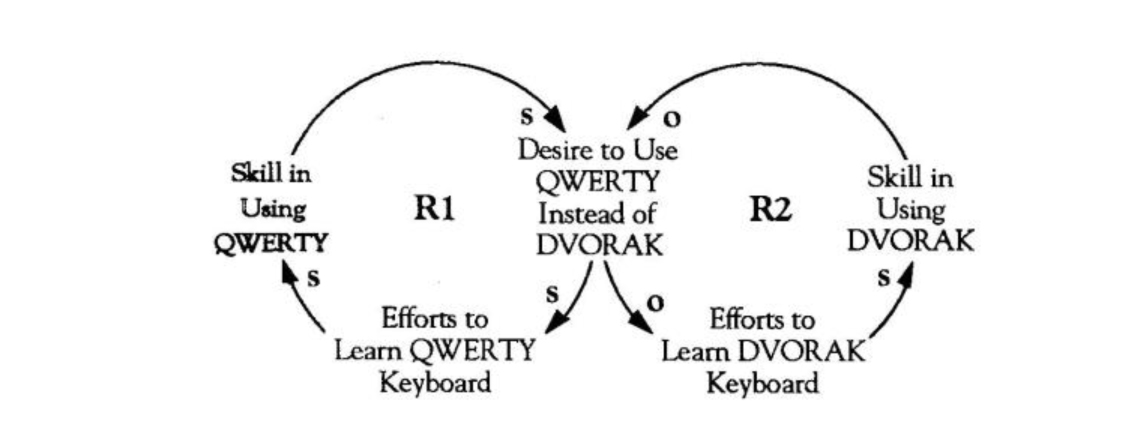

QWERTY Success Loop

1. Investigate Historical Origins of Competencies

One warning signal that the “Success to the Successful” archetype is at work is if you hear yourself validating decisions by saying, “X is a good way to go, because it is clear by the progress to date that it outshines all the other alternatives.” A critical first step in using “Success to the Successful,” therefore, is to investigate the historical origins of a chosen course of action.

The QWERTY keyboard, for example, was intentionally designed to slow typists down because mechanical keys would jam if a typist was too fast (see RI in “QWERTY Success Loop”). Although the mechanical problem of jammed keys no longer exists, attempts to replace QWERTY with a superior design (e.g., a DVORAK keyboard) have had little success (R2). The QWERTY system has become entrenched because of the “Success to the Successful” loops and is difficult to dislodge because of the “competency trap” phenomena.

2. Identify Competency Traps

Competency traps lock us into a particular way of doing things simply because we are already skilled at doing it that way. Suppose, for example, you bought a software package and have become adept at using it. When a new software is released, everyone raves and says it is superior to the first. But you think, “I already know how to use this one, so I’m just going to keep using it.” Each time you use it, you invest more of your rime and resources to get to know it better, without gaining any skills in the alternative software. Over time, your competency “traps” you into continuing to use that package.

Such competency traps can turn your organization into a corporate dinosaur because they disconnect you from current progress and engender the belief that you have the way, the best way, or the only way. Even if your favored method is currently superior, once you get caught in the “Success to the Successful” loops, you won’t realize it when progress passes you by.

3. Evaluate Current Measurement Systems

The measurement systems you use can perpetuate your competency traps by making current successes look good and other alternatives appear less favorable than they actually are. Is your current system weighing too heavily the costs that have already been invested? Does it overly discount the opportunity costs of not switching or not scanning for other possibilities? If you think your system may be skewed in one direction, you may need to question the assumptions behind your current measurement systems and perhaps change them if necessary.

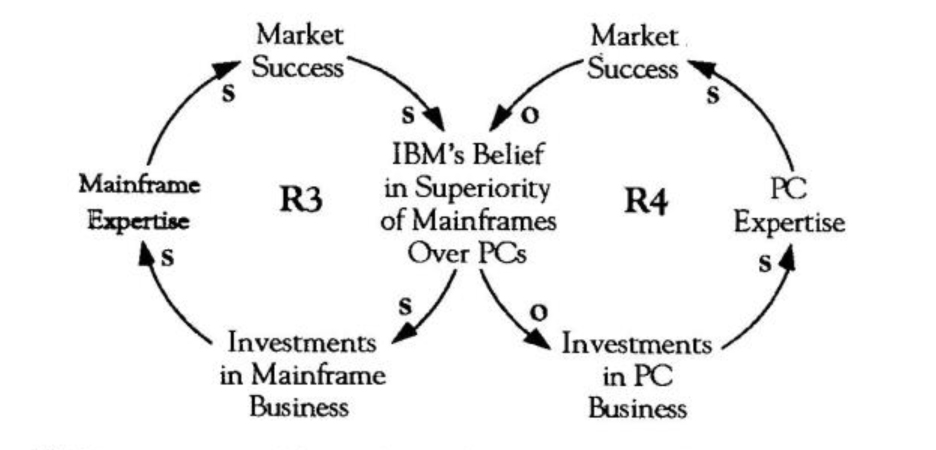

Internal View of Success

4. Map Internal View of Market Success

When you are successful in a market for a long time, you often begin to believe that your internal view of success is the same as the market’s view. The internal success loop can thus blind you to shifts in the competitive environment that are obvious to less successful players. Mapping your internal view of success will make the operating assumptions explicit and clear.

5. Obtain External Views of Market Success

To complete the picture, you need to obtain external views of market success. This usually requires getting an assessment from a true “outsider” to the organization or industry. Internal attempts to map the external view run the danger of looking too similar to the internal view. IBM, for example, had a very successful mainframe business that rein-forced its belief in the superiority of mainframes over emerging alternatives (see R3 in “Internal View of Success”). IBM therefore made relatively little investment in the PC business, which translated into little success in that market arena (R4). The arrival of personal computers did not change IBM’s internal view of success (customers want and need mainframes), so the company was slow to respond to the challenge of the market’s view of success (customers want cost-effective computing solutions such as PCs).

6. Assess Effects on the Innovative Spirit

Competency traps and inaccurate views of the marketplace indicate how the “Success to the Successful” archetype can erode the innovative spirit of the organization. This trap is characterized by the old management adage, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Instead of allowing one successful way to predominate, use the archetype to question how you think and perceive. The challenge here is to always entertain alternatives in a highly innovative spirit.

7. Be Your Best Competitor

By nurturing an innovative spirit and continually scanning for new alternatives, you can become your own best competitor. With this mindset, you become the most critical of your own success, continually looking for gaps and areas for improvement. For example, Proctor & Gamble’s approach of having multiple brands compete with each other helped the company become and remain the industry leader in many markets. By viewing your successes as if you were another company, you can find ways to create a competing product or service that may be better or more successful.

“Success to the Successful” is one of the toughest structures an organization has to overcome because many choices are often made subconsciously, influenced by the momentum of past actions. It is easy to become trapped in your success by continuing to learn how to do the same thing better. Applying the archetype can hopefully help you design your successes to be a product of continual learning rather than the inertia of past achievements.