Traffic jams . . . overfishing the Atlantic . . . last minute holiday shopping at the mall. A “Tragedy of the Commons” occurs when a system encourages individuals to take action for one’s own benefit, but gives little or no leverage at the individual level for responding to the collective result of those actions (see “Tragedy of the Commons: All for One and None for All,” August 1991).

In such a situation, the complex interaction of individual actions produces an undesirable collective effect (see “Tragedy of the Commons Archetype”). To paraphrase David Bohm, each player contributes to the problem, but then says “I did not do it.” Recognizing when you are operating in a “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype is important for understanding the long-term effects of individual actions, connecting those actions to the collective outcome, and finding the leverage for effective intervention.

Lack of Empowerment

The strategy behind employee empowerment programs is to step back and allow individuals to solve problems at the local level without interference from above. But telling individuals to solve a problem themselves can be demotivating when the solution does not lie at the individual level. This can create the “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” dilemma that many people feel in organizations. The long-term effect can be a sense of powerlessness and futility among employees.

Becoming aware of “Tragedy of the Commons” structures in your organization can be the first step toward empowerment. Instead of being forced to react or rebuild the commons later, the greatest leverage lies in identifying the structures in advance. The seven-step process outlined below provides a blueprint for using the “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype to discover these potential leverage points.

The process of using the archetype can be broken down into two stages: assessing the current situation and highlighting potential problems (steps 1–4); and identifying leverage points for action (steps 5–7).

Diagnosing the Problem

1. Identify the Commons

The first step in using the “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype is to identify the commons—the resource (broadly defined) that is being shared by a group of people. To pinpoint the commons, try looking for shared resources that are considered to be fixed for the time horizon of interest.

For example, in a car development program, the power output of an alternator is considered fixed, even though it may be later redesigned. The potential for a “Tragedy of the Commons” lies in the fact that the component design teams are vying for that fixed alternator capacity to power each of their respective parts.

2. Determine Incentives

Next, identify the reinforcing processes or incentives driving the individual use of the resource. These can be both personal motivators as well as incentive systems that exist within the company (e.g., sales quotas and contests). Bear in mind that sometimes the incentives are not that explicit (personal motivations are often involved).

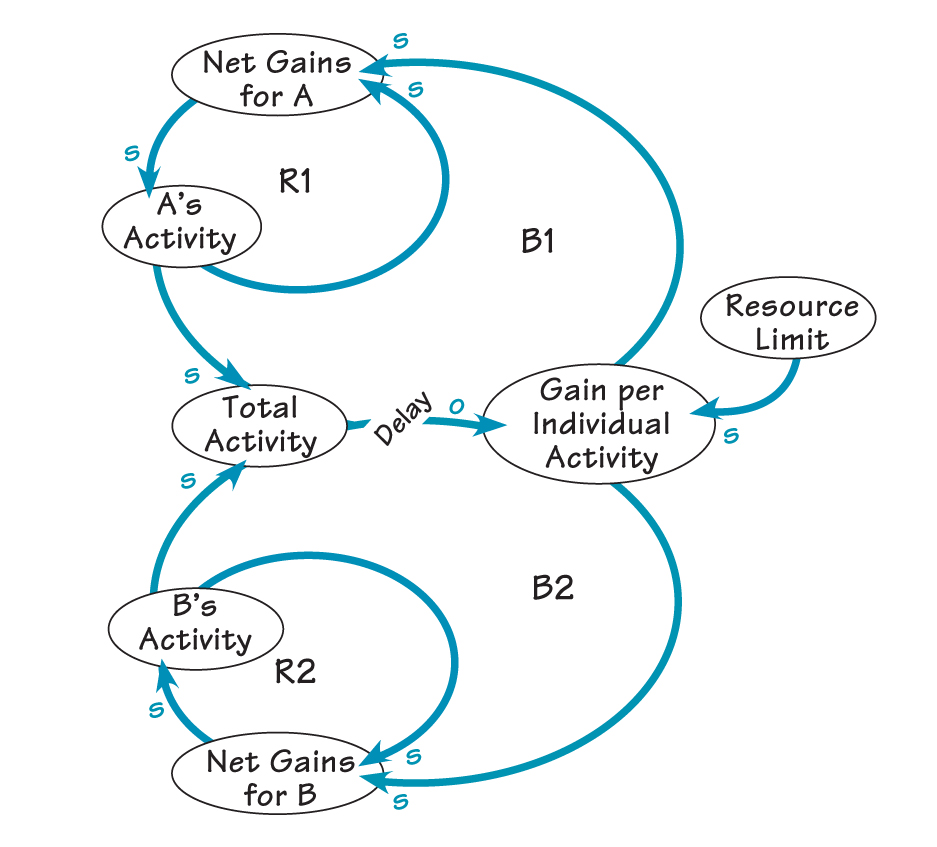

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS ARCHETYPE

In “Tragedy of the Commons,” each person pursues actions that are individually beneficial (R1 and R2), but eventually result in a worse situation for everyone (B1 and B2).

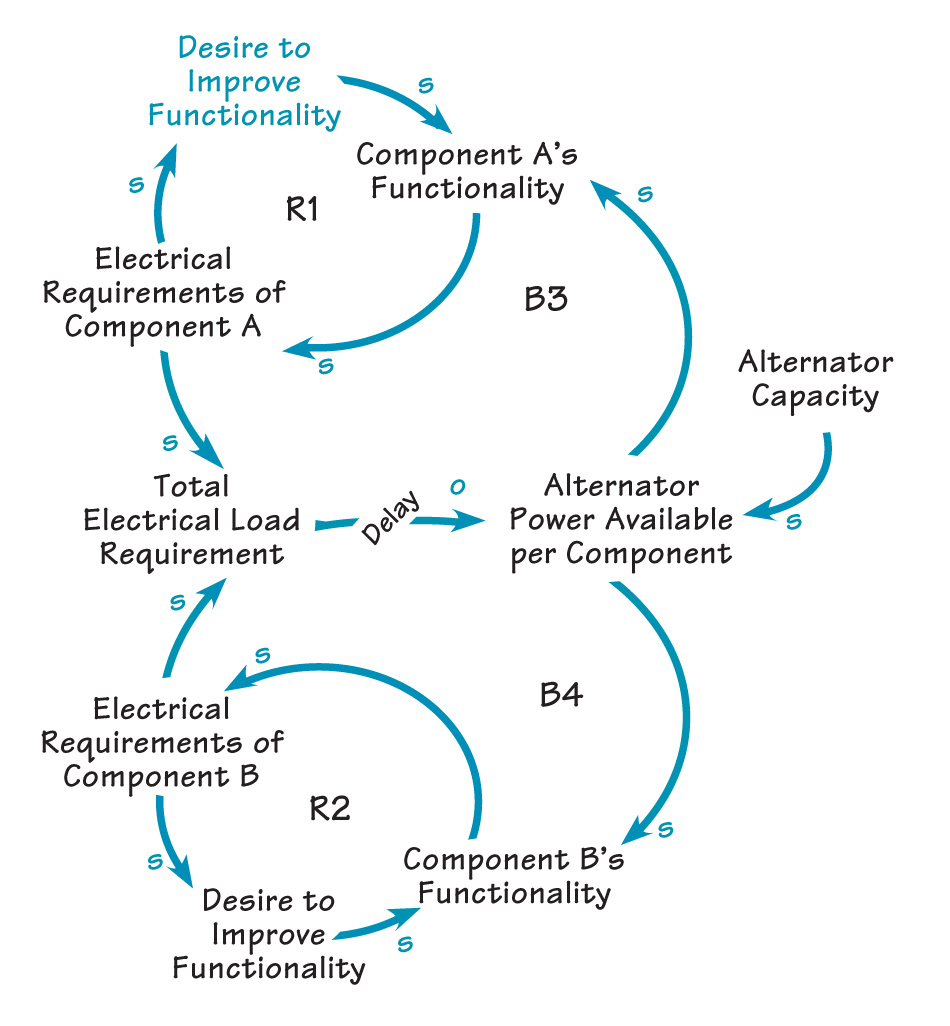

In the alternator case above, the engineers’ genuine interest to experiment and continually improve the functionality of each part can end up outstripping the available alternator power. The incentive for each component team, however, is to deliver improved functionality—not to manage the overall load on the alternator (loops R1 and R2 in “Overgrazing the Alternator”).

3. Determine Time Frame for Reaping Benefits

Having listed the incentives, it is important to determine the time frame in which the individuals reap the benefits of using that commons. This helps to estimate how fast the commons could become overgrazed. Generally, the shorter the time frame for reaping benefits, the higher the incentive to use the resource, and the more difficult it may be to get people to give up the short-term benefits for the long-term good.

4. Determine Time Frame for Cumulative Effects

The danger of “Tragedy of the Commons” is that the resource depletion can happen invisibly over a long period of time (due to cumulative effects). When the effects finally hit, you may suddenly find yourself paralyzed, without any lead time to take effective action. Trying to determine upfront how long it may take before the impact of the collective action will be felt can help you gauge the window of opportunity for taking effective action.

In the alternator example, as each team increases the functionality of its component, the electrical load may begin to rise. The collective effect may not be known for weeks, however, due to delays in getting accurate information collected and tabulated. When the total load exceeds capacity, the effect on everyone will be a degradation of component performance (loops B3 and B4).

Finding the Leverage Point

5. Make the Long-Term Effects Real and Present to Individual Actors

Once you have determined the parameters of the problem—the commons, the incentives, and the time frames—you can begin exploring alternatives for creating effective action. One approach is to make the long-term loss more real and present to the individual users. Most likely, in a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation, there is a large gap between how quickly one feels the benefits of an individual action (step 3) versus the pain one will eventually feel from the collective result (step 4).

OVERGRAZING THE ALTERNATOR

The desire of the teams to improve the functionality of their components can lead to an overload of the “commons”—overall alternator capacity

One way of closing the gap is to develop a measurement system that will translate the cost of the future loss into a net present value equivalent. Providing immediate, systemwide feedback on the effects of individual actions and tying them to performance measures can help make the link between local action and global consequences more real and immediate. In the alternator example, we may be able to show in real time the overall system degradation each additional demand for power creates.

6. Reevaluate the Nature of the Commons

In many “Tragedy of the Commons” structures, such as those associated with the ecology of the planet, there is an eventual “collapse” of the commons. Once you reach a certain limit, the commons cannot be replenished.

In most corporate settings, however, there is not a final “collapse.” Most common resources are renewable (eventually). Replacing the resources, however, can take a long time. Another possible leverage point in a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation, therefore, is to remove the constraints imposed on the commons. Reevaluating the limit may produce some alternatives or possibilities that have not been considered.

In the alternator scenario, for example, we may consider other available technologies that could give us more electrical power. The Japanese often prepare for this eventuality by innovating and creating alternative technologies and putting them on the shelf even before they have a use for them.

7. Role of the Final Arbiter to Limit Access to Resources

The highest leverage in a “Tragedy of the Commons” is to find the central focal point around which the whole resource can be managed. That could be either a common shared vision that will guide all individual actions, a measurement system that somehow accounts for the collective effect (and makes it “visible” to each player), or a final arbiter who controls and allocates the resource based on the whole system.

One way of creating an overarching vision to guide a project is to apply Quality Function Deployment, which translates customers’ needs into a matrix that provides a blueprint of what the customer values most. This way, even as each team tries to optimize its part by using the common resource, the matrix shows which ones should get higher priority.

One example of a final arbiter is the heavyweight program manager common in car product development programs in Japanese companies. He or she has a great deal of authority for making decisions about design and resource allocation issues.

Empowerment

How many times have decisions been made at a higher level in an unrecognized “Tragedy of the Commons” where individual morale and empowerment suffer as a result, even though the decision was the “correct” one? Recognizing a “Tragedy of the Commons” at work can be an empowering experience. When people realize a particular problem cannot be “solved” at the individual level, they will feel much more comfortable about the decisions being made at higher levels and also understand at what level the decisions need to be made.

The “Tragedy of the Commons” example used above is based on “Learning to Learn: A New Look at Product Development” in the February 1993 issue of The Systems Thinker®.

Daniel H. Kim is co-founder of Pegasus Communications, founding publisher of The Systems Thinker newsletter, and a consultant, facilitator, teacher, and public speaker committed to helping problem-solving organizations transform into learning organizations.