You won’t find Detroit, Philadelphia, or Los Angeles listed in Fortune’s 1993 ‘Top Ten Cities For Business.” In the last four decades, Detroit has lost 42 percent of its population as residents have followed the jobs to the suburbs. After last year’s riots, Los Angeles ranks last in race relations, in addition to having a reputation for high costs and taxes. And no other single metropolitan area faces as much fiscal desperation as Philadelphia, which lost 400,000 residents and 200,000 jobs between 1970 and 1990.

These stories are not unique to Detroit, Philadelphia, or Los Angeles, nor are the dynamics unique to cities. IBM, once the paragon of business excellence, has laid off more than 100,000 employees and seen its market value tumble from a high of $106 billion in 1987 to $29 billion in 1992. Digital, once hailed as the epitome of entrepreneurial success, has been experiencing its own share of problems. The story is the same at other, once-successful companies, such as General Motors and DuPont.

What happened to these cities and companies that were once so successful and attractive? How do once-vital neighborhoods descend into endless blocks of slums? How do long-time successful companies end up in such crises? Although these two questions may appear unrelated, the underlying structures that produce the dynamics have much in common.

Urban Dynamics

The 1969 book Urban Dynamics, written by founder of system dynamics Jay W. Forrester, identified and described the systemic structure responsible for the dynamics of urban development and decay. Through repeated computer simulations, Forrester analyzed the changing ratios of critical urban development factors such as population, housing, and industry, and how the changes would affect a city’s growth.

For example, if a particular city received financial aid from an external source, how would the assistance affect the city’s economic status?

One controversial conclusion in Urban Dynamics was that the most commonly-accepted plans for improving an urban area (such as financial assistance) may actually hurt a city’s long-term health. Financial aid, job training, other job programs, and low-cost housing were each found to be ineffective and potentially harmful for the city system because they can lead to other problems such as overpopulation and greater tax demands on the underemployed.

The descriptions in Urban Dynamics of these well-intended urban policies leading to disaster are currently visible in many cities. For example, an article in the January 27, 1992 US News & World Report described the 10 worst economic blunders made by state and local governments. “Local government officials from coast to coast, besieged by the demands of financially ailing citizens who want more services but fewer taxes, are hitting the economic panic button in order to retain their jobs. This hysteria has resulted in a series of wrongheaded and shortsighted decisions…[and] the long-term impact of these blunders is frightening. Budgetary quick fixes are driving herds of companies from high-tax cities and states to more inviting economic pastures. This stampede will ultimately burden the next generation of citizens with even more intractable deficits.”

Yet another piece stated, “Many of the troubles flow from conditions beyond the cities’ control. Despite all the talk of urban gentrification, city dwellers continue to move to the suburbs, eroding tax bases…(and) Reagan-era cutbacks have cost cities $20 billion in federal funding since 1981” (“Cities on the Brink,” Newsweek, November 19, 1990). Again, promising solutions such as increasing taxes and external financial aid have led only to higher unemployment in cities on the edge of bankruptcy. Blame is often placed on individuals, consumers, and the government, without recognition of the larger dynamics at work.

Forrester wrote Urban Dynamics over 20 years ago, decades after the first indications of urban decay appeared. Twenty years later, we are still far from understanding the counterintuitive dynamics at work and how we can use those dynamics to manage urban growth.

Boom and Bust of Urban Dynamics

The Dynamics of Booms and Busts

How, exactly, does a city experience a rise and fall in growth and attractiveness? The story usually begins with a “hot” city being perceived as the new “best” place to work, live, and raise a family. Construction in the city is booming, so employment is on the increase. People are starting to move from other regions to “HotTown” for the abundant job opportunities. During the years of expansion, the job growth is not just in construction work, but in all the ancillary business that the work generates. Attorneys, accountants, engineers, architects, designers, and many other professionals are needed which, in turn, fuels demand for print shops, restaurants, supermarkets, and department stores.

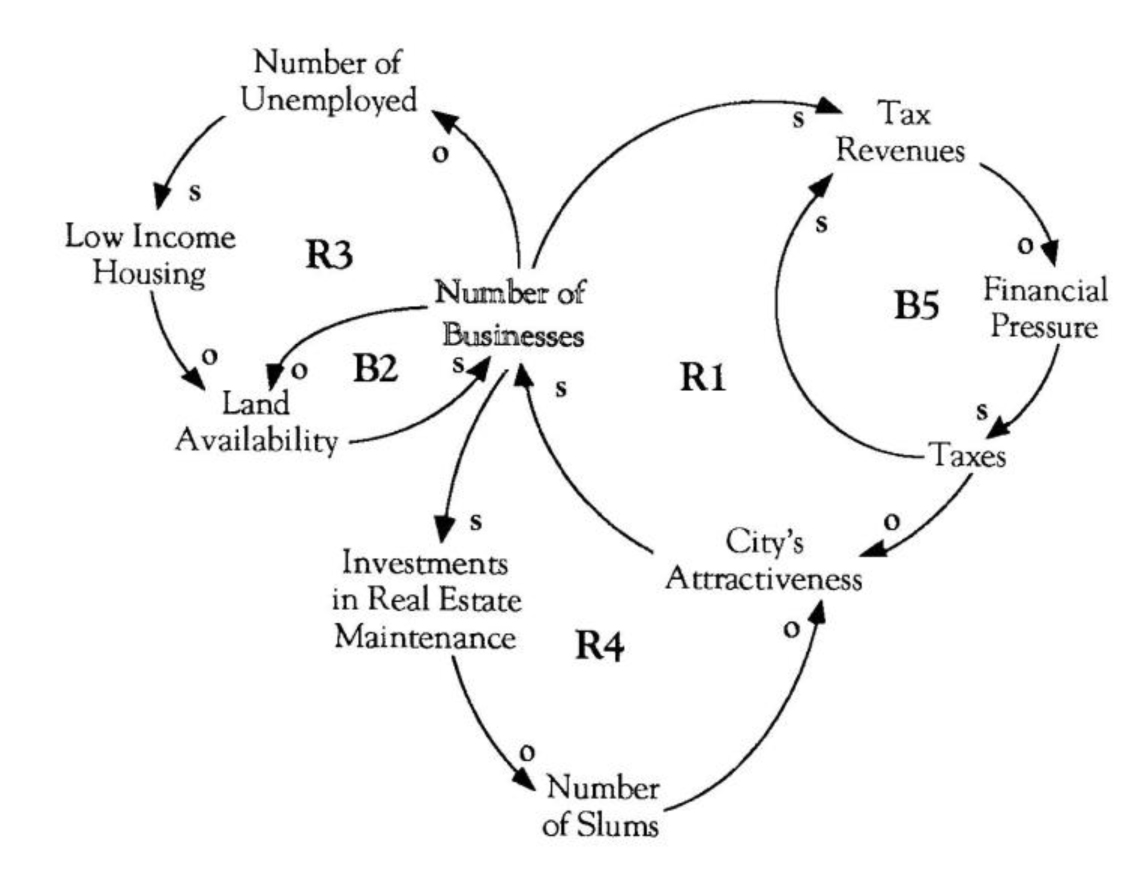

Over a number of decades, the city boundaries expand out as far as possible, as industry and people pour in and the land area begins to be filled. “Hot-Town” thrives on a growth loop that is virtuously fed by reinforcing cycles of business immigration and tax revenues (loop RI in “Boom and Bust of Urban Dynamics”).

As growth continues, availability of land grows scarce, real estate prices increase, and growth in the number of businesses slows (B2). The city’s attractiveness decreases and construction slows down. Unemployment rises as the construction boom ends, sometimes leading to the establishment of low income housing for the poor and underemployed. This, in turn, further reduces the availability of land for business use (also eroding tax revenues), and continues the decline of businesses in the city (R3). As businesses disappear, building maintenance declines and leads to abandoned buildings and slums, further lowering the city’s attractiveness and driving even more businesses away (R4). With the loss of businesses come the loss of tax revenues, which creates financial pressures. Raising taxes fixes the revenue problem in the short term (B5), but creates another vicious cycle of business emigration (R1).

Philadelphia is a case in point. During the decade from 1952-1962, Philadelphia was a vibrant city, where businesses thrived under the leadership of mayors Joseph S. Clark and Richardson Dillworth. Its glory days are long gone, however. In 1991, its public transportation system was threatened with imminent bankruptcy and the city of “brotherly love” found its voters racially polarized. The wage tax of almost 5% is one of the highest in the country and the garbage disposal fees (also among the highest) are widely blamed for the mass exodus of businesses from the city to the suburbs. A construction boom did revitalize downtown Philadelphia in the 1980s, but generous property-tax concessions to developers limited the city’s ability to profit from the growth.

Counterintuitive Nature of Complex Systems

According to Forrester, the counterintuitive discoveries in Urban Dynamics are indicative of the nature of all complex systems. Pushing on one facet of a system will eventually create repercussions in other, seemingly unrelated areas. Any city improvement program will change the balance of the system as a whole, regardless of the individual program’s potential. For example, every city has a natural rate of upward mobility through which the unemployed move into the labor pool. if a city becomes dependent on job training programs to spur such growth, other job-creating initiatives will be deemphasized. Because of this shift, you can never experience a positive program’s full benefits.

Therefore, in any complex system, the most obvious solutions are those most likely to fail. Forrester wrote in Urban Dynamics, “With a high degree of confidence we can say that the intuitive solutions to the problems of complex social systems will be wrong most of the time. Here lies much of the explanation for the problems of faltering companies, disappointments in developing nations, foreign-exchange crises, and troubles of urban areas.”

In addition, any kind of complex system is almost always accompanied by a conflict between short and long-term thinking. Such dynamics play out frequently in business situations, where short-term thinking and quick results are often rewarded. In many companies, annual and sometimes quarterly reports are considered to give accurate indication of the organization’s health, when, in reality, they provide only a narrow view of the company’s position. Budgetary and political pressures often result in decisions that will have positive results in the short term, but negative consequences over the long term.

Boom and Bust of Information Dynamics

Overbuilding and Collapse of Corporate Infrastructures

Companies also create their own “inner slums” through dynamics similar to those Forrester described for cities. The need to revitalize these areas is often unplanned and unanticipated. But as many companies are being forced to restructure and rethink their work processes, managers are being challenged to openly face these issues while attempting to restore economic “health” to their departments and to their business as a whole.

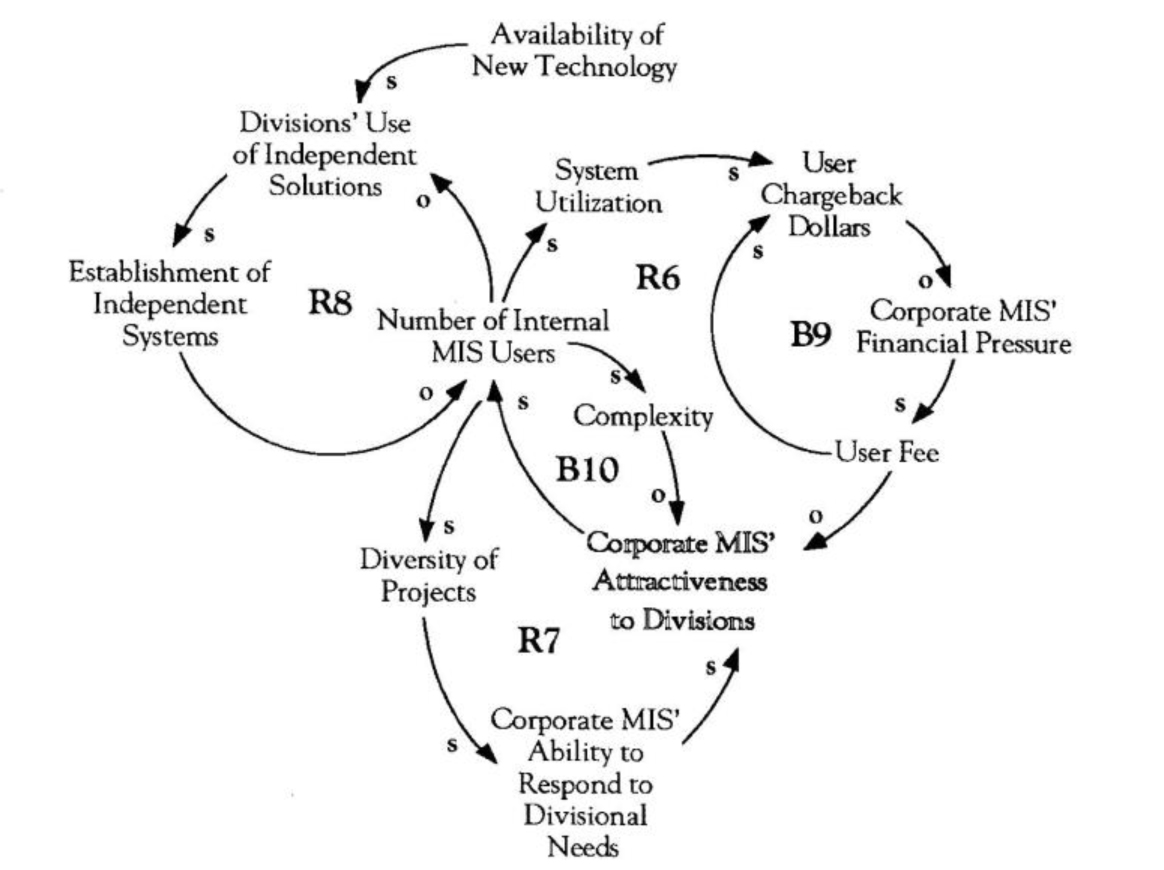

For example, management information systems (MIS) in some companies have sprawled out throughout the organization through haphazard growth (see “Boom and Bust of Information Systems”). To meet the growing needs of the company, corporate MIS expands (R6). As it grows, the systems become more complex and less attractive to use (B10). New available technology offers other, sometimes more cost-effective options, so individual corporate divisions choose to find independent solutions, therefore establishing more independent systems (R8). As more and more users defect, chargeback dollars fall, placing more financial pressure on corporate IS, leading to higher user fees (B9) that further decrease its attractiveness (R6).

Cutbacks and limited returns from past investments are currently placing budgetary demands on MIS, as managers are under increasing pressure from upper management to justify the cost of their operations. Readily-available technology has quickly complicated and decentralized what were once purely mainframe systems. The quick transition to microcomputers and lack of an integrated plan and direction have led to many overbuilt departments with underutilized technology. In many cases, poor organization and planning is sometimes credited for the mismatch between needs and resources.

“One source of this (MIS] problem is the way the development process typically is organized. Information systems’ applications are often developed in isolation, with each team working on one particular application…Thus the process becomes organizationally as well as technically fragmented. The result is a set of applications that may work individually or in isolation, yet the overall system represented by the organization’s collective set of applications may fail to perform adequately or to support the organization’s needs.”

Cities and companies have always been controlled; if not by the designers and architects, then by the complexity of the system itself. By continuing to build and add technology, we force the system to choose its own limits, and therefore create the very destruction we want to avoid.

These shifts in the structure of MIS workflow may have been better anticipated and planned for, given the quick changes and outdating of computer systems. Instead of creating a sustainable system, many MIS departments are now being challenged to maintain their outdated systems because of the hefty financial investment, while trying to keep pace with new technology. In trying to address these issues for the long term, chief information officers are beginning to return to the basics of information management — cost reduction and modernization. Benchmarking is also becoming more prevalent as a way for MIS departments to establish performance bases for continuous improvement.

Manage Growth — Don’t Be Its Victim

MIS is not alone in its resemblance to urban dynamics. Internal purchasing, accounting, sales, support, and administrative departments are also susceptible. A better understanding of the dynamics can help us learn to manage growth to create the kind of long-term results we desire. Advocates of free market systems may see this kind of managed growth as an attempt to control too much by placing limits and minimizing opportunity. Cities and companies, however, have always been controlled; if not by the designers and architects, then by the complexity of the system itself. By continuing to build and add technology, we force the system to choose its own limits, and therefore create the very destruction we want to avoid.

The Attractiveness Principle

The same can be said about companies who try to be the most attractive in every dimension. A single company cannot maintain a superior position in every attribute because smaller niche players will always be able to focus on specific elements (e.g., cost, features, responsiveness) and do as well or better. Even if a company were able to start out of the top in all categories, the market response will overwhelm its capacity to deliver on all fronts and force some dimension of their attractiveness to decrease (see pp. 5-6, “The Attractiveness Principle: Trying to Be All Things to All People”).

In attempting to design any system that can grow sustainably and support the needs of the whole, departments such as MIS and their parent companies can learn from Urban Dynamics. Applying the lessons of Urban Dynamics may help us learn to balance more carefully the forces of attractiveness and growth to create sustainable cities and companies. Avoiding the creation of slums altogether will therefore require learning how to manage the dynamics of growth rather than be a victim of them.

Forrester suggests urban planning should focus on how to balance the positive and negative dimensions of urban life (see “The Attractiveness Principle”). Changing specific components of a city’s attractiveness, while ensuring that the total attractiveness of the city remains the same, can help in managing a city’s development. The key is to focus on the particular core competencies that will create sustainable health over the long term. The author would like to thank Michael Goodman of Innovation Associates (Framingham, MA) and Jay W. Forrester of MIT Sloan School of Management (Cambridge, MA) for their contributions and comments. Sources:

Boroughs, Don L. “The 10 Worst Economic Moves.” US News & World Report, January 27, 1992.

Forrester, Jay W. Urban Dynamics. (Portland, OR: Productivity Press, 1969).

Forrester, Jay W. “Counterintuitive Behavior of Social Systems,” Chapter 14, Collected Papers of Jay W. Forrester. (Portland, OR: Productivity Press, 1975).

Zack, Michael H. An Information Infrastructure Model for Systems Planning.” Journal of Systems Management, August 1992. For additional resources, please contact Pegasus Communications at (617) 576-1231.