Managers in today’s organizations are continually confronted with new challenges and increased performance expectations. At the same time, they are bombarded by a bewildering array of management ideas, tools, and methods that promise to help them solve their organizational problems and improve overall performance. Desperate to find solutions to intractable problems, beleaguered managers may succumb to the lure of new techniques and approaches that promise easy answers to tough issues. When they try the latest management fad, however, they find that the relief is only temporary; the same issues resurface later, perhaps in another part of the organization.

Managers often don’t have the time, perspective, or framework to learn from the successes and failures of their problem-solving efforts. As a result, organizations fall into a recurring pattern of temporary relief followed by a return of the same problems. If people do attempt to learn from the past, they frequently find themselves ill-prepared to make sense of their own experience. Even in cases where the solutions produce lasting results, managers often lack an understanding of why these approaches succeeded.

A CORE THEORY OF SUCCESS

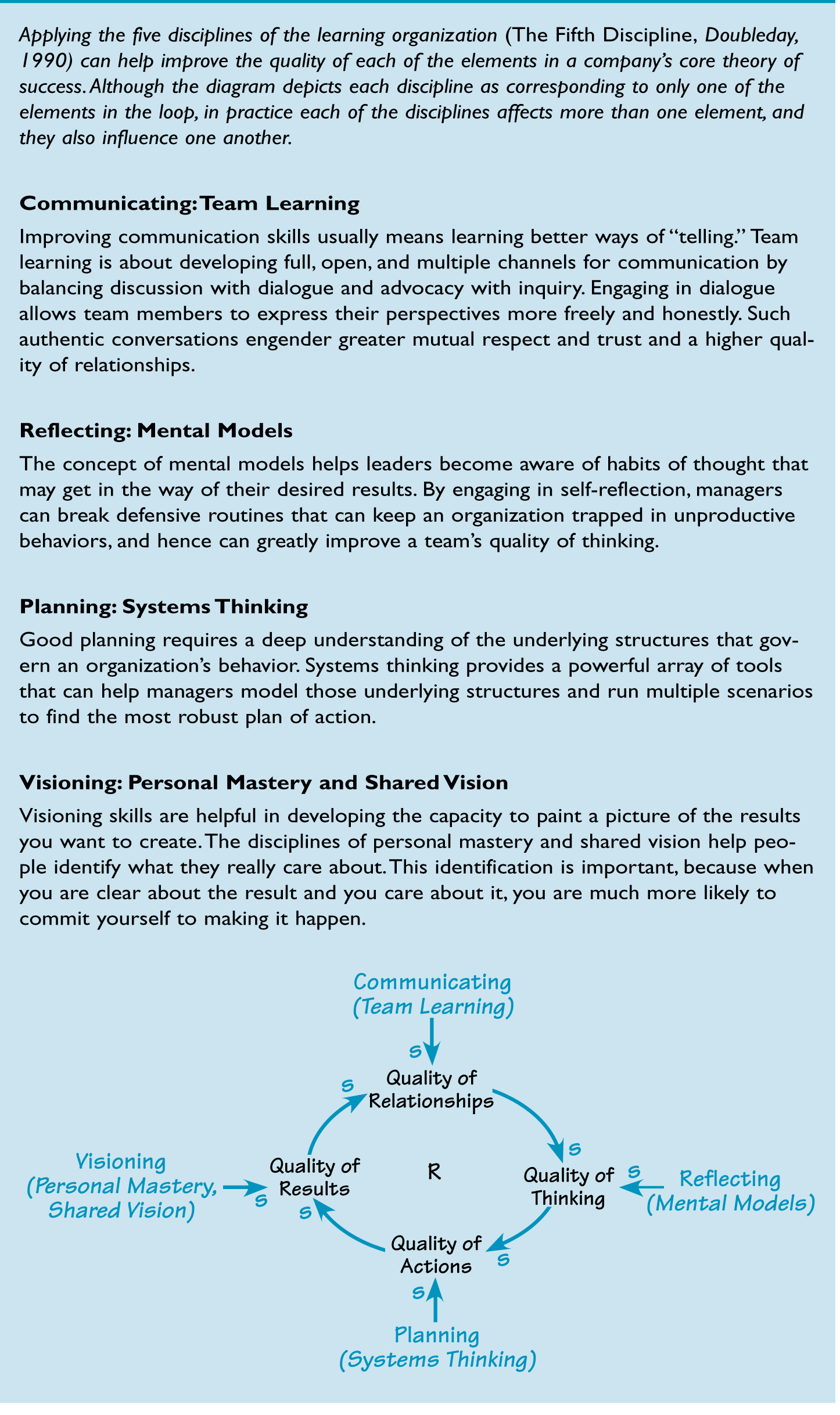

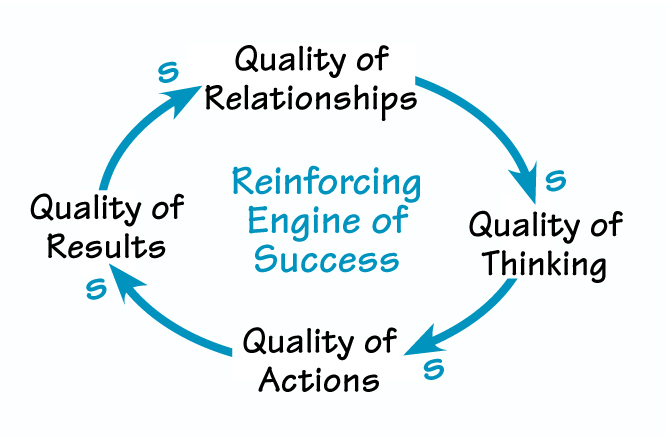

As the quality of relationships rises, the quality of thinking improves, leading to an increase in the quality of actions and results. Achieving high-quality results has a positive effect on the quality of relationships, creating a reinforcing engine of success.

Limitations of Traditional Approaches

When attempting to determine why an initiative succeeded, most managers talk in terms of the individual factors they believe were critical to the success. This propensity to focus on factors in isolation rather than seeing them as interrelated sets is part of what Barry Richmond refers to as “traditional business thinking” (“The ‘Thinking’ in Systems Thinking: How Can We Make It Easier to Master?” March 1997). Indeed, many companies formulate their thinking about success as lists of important attributes or competencies, without identifying the key ways in which the items are connected.

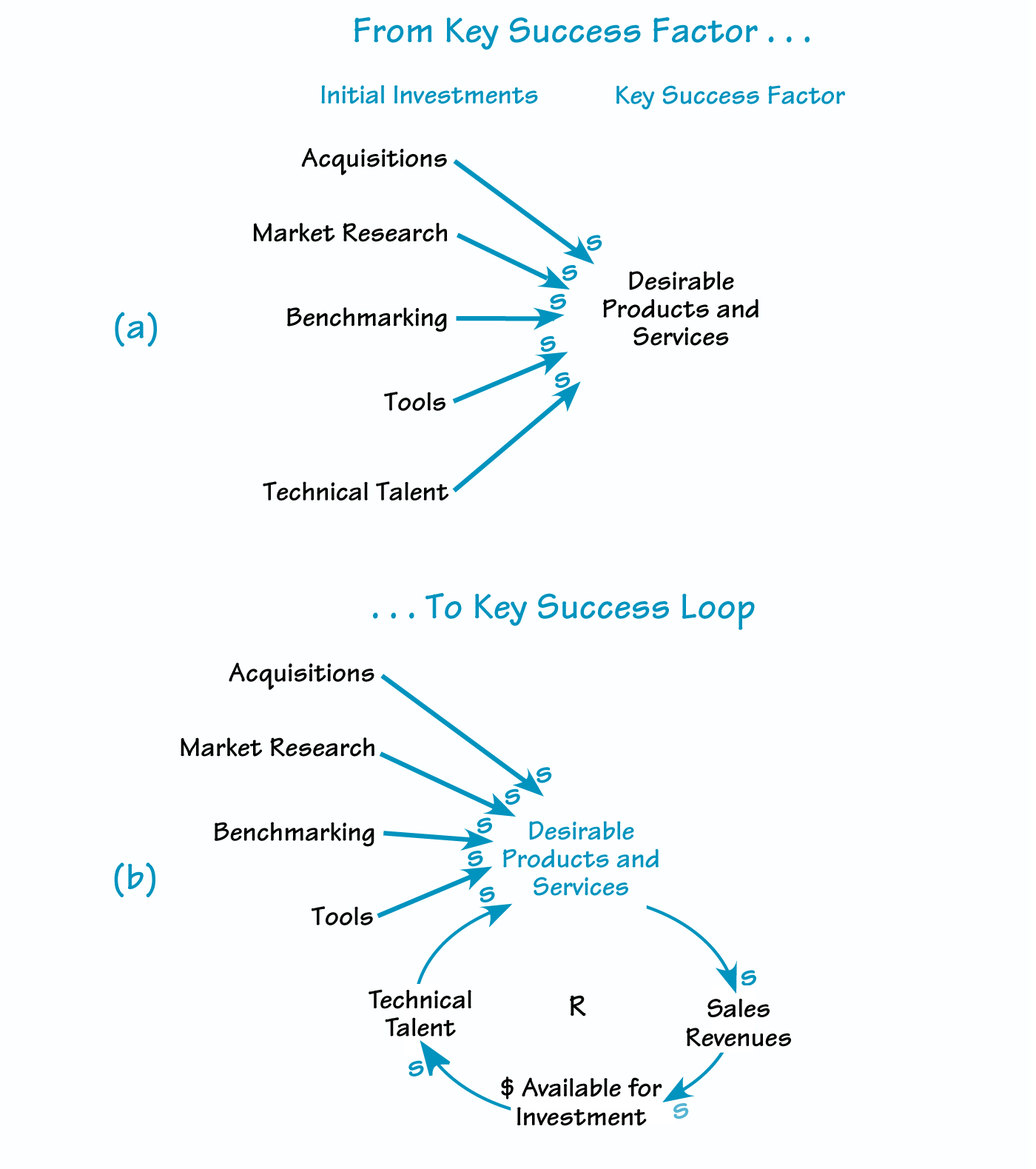

For example, companies often begin their efforts to improve their organizations by listing critical success factors. They identify a goal (for example, industry leadership) and then list the factors that management agrees are essential to achieving this goal (such as desirable products and services, ability to deliver). They then prioritize the items on the list and assign the top priorities to special teams. This list-based approach poses several problems. First, people frequently treat the factors separately, in a “divide and conquer” strategy. The danger here is that they may not properly consider important interactions among the different factors. Hence, a marketing department may not warn manufacturing and customer service about the potential impact of a major marketing campaign.

Another problem is that if management reduces the initial investments after a key success factor (KSF)has reached a certain desired level, the success may prove temporary. Often, when we have achieved a certain desired level with KSF1, we declare victory and shift resources over to KSF2. As we build up KSF2 and then KSF3, KSF1 starts to deteriorate because of lack of continued investments. So, we shift some resources back to KSF1 as we declare victory on KSF2 and KSF3.

Unless managers develop a theory of how these factors are interrelated in creating ongoing success (or failure), they cannot put the data from their experiences together in a way that serves as a guide for future actions. Unfortunately, most approaches to helping organizations solve persistent problems focus on applying other people’s theories and methods to the organization and not on developing a specific theory about the organization’s own operations. Systems thinking and organizational learning can offer tools and methods for companies to begin developing such theories and for putting them into action.

The Importance of Theory

Regrettably, the corporate world has little appreciation for the importance and power of theory. Many managers associate theory with universities and research institutions, which they view as too insulated from the real world. Hence, managers often dismiss theory as too academic and irrelevant to the pragmatic conduct of business. But the American Heritage Dictionary, Standard Edition, defines theory as “systematically organized knowledge applicable in a relatively wide variety of circumstances, especially a system of assumptions, accepted principles, and rules of procedure devised to analyze, predict, or otherwise explain the nature or behavior of a specified set of phenomena.” This definition clearly shows that there is nothing strictly academic about the concept of theory at all.

Using this definition of theory, we can say that creating a long-lived, successful organization means managers must develop systematically organized knowledge that represents the system of assumptions, accepted principles, and procedural rules they use to make sense of their past experience and to predict the future. In this sense, theory building is about developing a better understanding of our organizations and improving our capacity to predict the future. In other words, theory-building has everything to do with running a successful business.

We have to be cautious when we use the word “prediction,” because it tends to be used interchangeably with the word “forecast.” Forecasting attempts to provide a specific kind of prediction; however, it usually focuses on calculating specific numerical data that we expect to occur at some point in the future. The main criterion of success for forecasts is the accuracy of the result, not the accuracy of the assumptions or the methods used to produce it.

When we talk about predictions based on theory, however, we are more interested in the accuracy of the underlying assumptions and less in the numerical accuracy of the predicted result. Why? Because, in a complex world that is inherently unforecastable (a basic tenet in the emerging science of chaos), only understanding interrelationships can guide us in making the course corrections inevitably required in an environment of rapid and continual change. All good theories therefore help provide guidance by increasing our predictive power about the future

Theory-Building: Shifting from Factors to Loop

So, responsible leaders should ask themselves, “What good theories do we have that provide practical guidance for ensuring our organization’s future success?” The more clearly you can articulate your organization’s theories about what leads to success, the more deliberate you can be about investing in the elements that are critical to that success. From a systems thinking perspective, having a core theory of success means moving beyond identifying individual success factors to seeing the linkages that create the reinforcing engines of success within the organization.

For example, once we have a list of key success factors, we can take the next step of identifying how each KSF is connected to a reinforcing loop (see “Shifting to a Loop Perspective”). The key success loop (KSL) identified in our example shows that by increasing desirable products and services, we increase sales revenues and boost the amount of money available for investment. With more money to invest, we can draw more technical talent and produce even more desirable products and services (R loop).

Shifting our formulation of theories from factors to loops is important for several reasons. First, it forces us to think through the logical chain of causal forces that ensure that the KSF becomes self-sustaining. Second, it shifts our emphasis away from the factor itself to the broader set of interrelationships in which it is embedded. Third, by mapping each of our KSFs into Key Success Loops, we are more likely to see the interconnections among all the KSFs. This approach requires shifting our worldview from one that sees factors as the lowest unit of analysis to one that recognizes loops as the basic building blocks of organizational systems.

Theory as an Intervention Guide

Having an explicit theory of success allows an organization to continually test the impact of planned actions and assess whether these actions are having a net positive or negative effect on the company’s overall success. So what might a theory of success look like in a learning organization?

One such core theory of success would be based on the premise that as the quality of the relationships among people who work together increases high team spirit, mutual respect, and trust), the quality of thinking improves (consider more facets of an issue and share a greater number of different perspectives) (see “A Core Theory of Success,” p. 1).When the level of thinking is heightened, the quality of actions is also likely to improve (better planning, greater coordination, and higher commitment). In turn, the quality of results increases as well. Achieving high-quality results as a team generally has a positive effect on the quality of relationships, thus creating a virtuous cycle of better and better results.

The most important point about this kind of systemic theory is that success is not derived from any one of the individual variables that make up the loop, but rather from the loop itself. All of the variables are important for the theory to work properly, because if one of them isn’t functioning, there in forcing process doesn’t exist. If we believe that this loop describes a relevant theory of success for our organization, it forces us to pay attention to how all the variables are doing and how each is affecting the others in the loop.

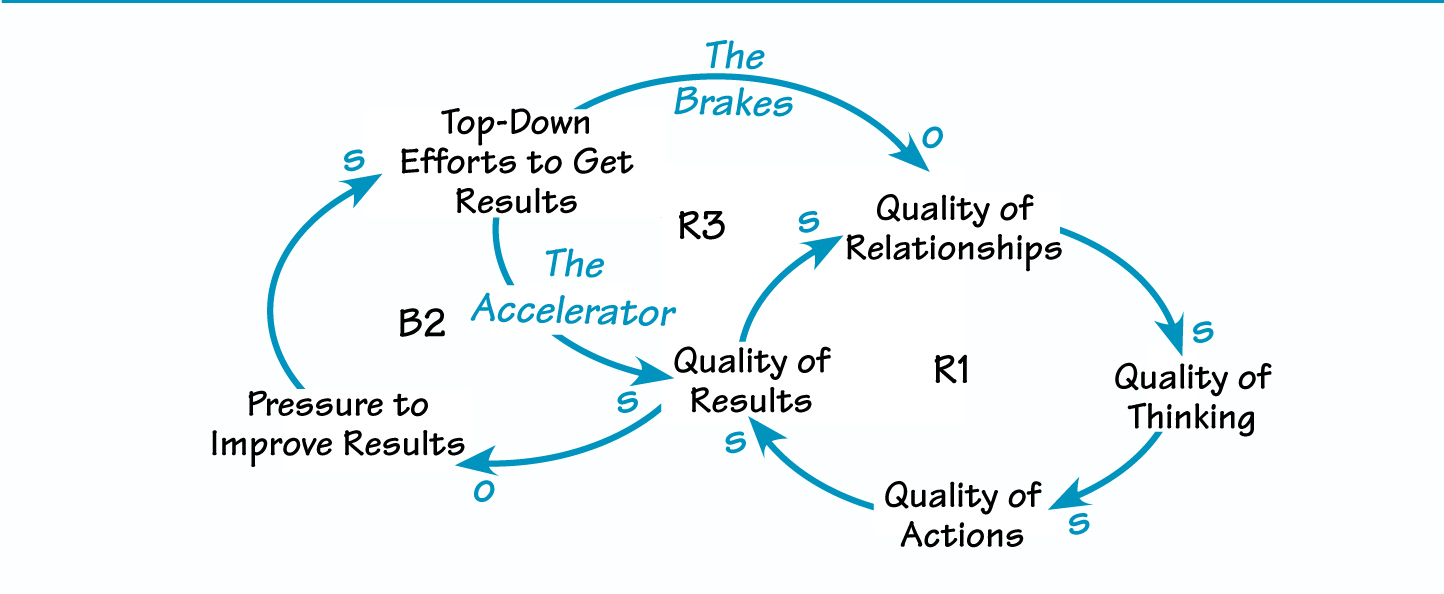

As an example, we can use this Core Theory of Success to trace the implications of a common occurrence in corporations—top-down organizational efforts to get quick, short-term results. When results fall short of expectations, management often “helps” the people below by undertaking efforts intended to improve the bottom line immediately (see “Applying the Accelerator and the Brakes”). The “accelerator” (say, downsizing) works and improves the quality of results we are looking for (better profit picture). But those same action scan also serve as “brakes,” or unintended consequences that counteract any beneficial actions. These action scans destroy the quality of relationships by creating mistrust and low morale, and thus ultimately decrease the quality of results. The end result may be a lot of wasted energy with no real improvement in overall results.

Without having a core theory, we might simply focus on the “accelerator” aspect of the intervention and declare victory when the results improve in the short term. We wouldn’t necessarily connect the long term negative consequences of the “braking” action to the original intervention. When the results deteriorate again, the pressure to improve results increases. We might respond by repeating the same efforts that we believe worked so well the last time. By having the theory and the accompanying loop, on the other hand, we can see how the top-down efforts may have a negative impact and implement additional measures to counter balance that effect.

To illustrate how this generalized accelerator-and-brakes dynamic might play out in a specific situation, let’s look at an example. Curtis Nelson, president and CEO of Carlson Hospitality Worldwide (the parent company of Radisson Hotels), wrote in their company magazine: “Take care of your people, inspire them, allow them to grow to their full potential and evoke their personality, and they will reach a higher level of job satisfaction. That in turn inspires greater commitment, which leads to greater guest satisfaction.”

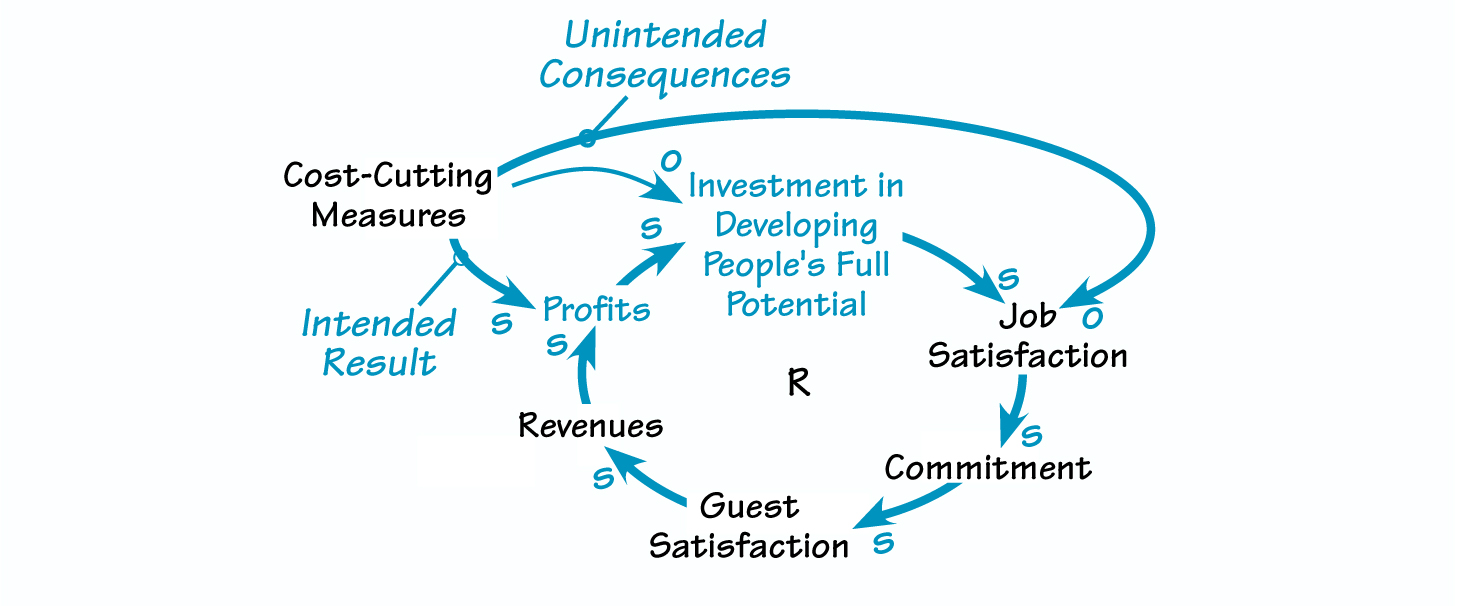

Although Nelson did not draw a loop in his article, he articulated in words his core theory of success for this hotel and cruise business (see “Hotel Core Success Loop”). The diagram shows that investments in people’s potential enhances job satisfaction, which builds commitment and translates into higher guest satisfaction and higher revenues. An increase in revenues means a rise in profits, which leads to more investments in people.

SHIFTING TO A LOOP PERSPECTIVE

Now, suppose something unexpected happens to decrease profits, such as a rise in airfares that reduces business travel. Top management might respond by calling for cost-cutting measures to improve the profit picture. In the short term, profits are likely to rise – the intended result. However, an unintended consequence of enacting such measures may be substantial decreases in the company’s investment in its people, leading to a decrease in job satisfaction. This decrease in job satisfaction will reduce profits in the longer term, because employees will be less committed, causing a decline in customer satisfaction. Lower profits would then provoke another wave of cost cutting, repeating the accelerator and brakes dynamic. In this way, a one-time disturbance from the outside can trigger an internal response that keeps cycling for a long time.

Again, by articulating our core theory of success, we will be more likely to pay attention to both the short-term and the long-term consequences of our actions. In particular, our theory can prevent us from inadvertently undermining the very loop, we depend on for our success.

Of course, in a real company setting, a core theory of success is likely to involve many loops, not just one. The various loops will be interconnected in many ways, and their dynamic behavior will not always be intuitively obvious. Building and understanding such theories requires more than a one-time investment in creating a quick overview map (like the ones in this article); it requires a shift in mindset that values theory-building as a vital ongoing activity of the organization.

Managers as Researchers and Theory-Builders

But in order to survive and thrive in the emerging economic order, organizations must focus on producing

APPLYING THE ACCELERATOR AND THE BRAKES

HOTEL CORE SUCCESS LOOP

long-term, sustainable results. Managers at every level need a broader perspective-a theory-of how their organization can create and maintain success. Theory-building can no longer be seen as a separate activity from the practice of management; it must become an integral part of a manager’s job. Managers must take on new roles as researchers and theory builders, which will require investment in the development of new skills and capabilities (see “Applying the Disciplines of the Learning Organization”). Just as we currently depend on accountants and financial statements to help us manage our complex enterprises, there may come a time when we will depend on our theory-builders and organizational maps and models to navigate the turbulent waters of tomorrow’s business environment.

Daniel H. Kim is a co-founder of Pegasus Communications, Inc., and a co-founder of the MIT Center for Organizational Learning.

APPLYING THE DISCIPLINES OF THELEARNING ORGANIZATION