These lines, from three American presidential inaugural addresses, are arguably the most famous from the 56 such speeches given since 1789. At the start of nearly every new president’s term (there are five exceptions), the newly elected or reelected head of state lays out their intentions and priorities for their forthcoming presidency. Inaugural addresses however are notoriously unmemorable (see www.bartleby.com/124/ for complete transcripts) and have even been known to be fatal (one unlucky orator, William Henry Harrison, caught pneumonia and died days later as a result of his two-hour speech in a snowstorm).

TEAM TIP

Explore whether your group responds to challenges as learners or knowers. If the latter, what could you do collectively to adopt a learner stance?

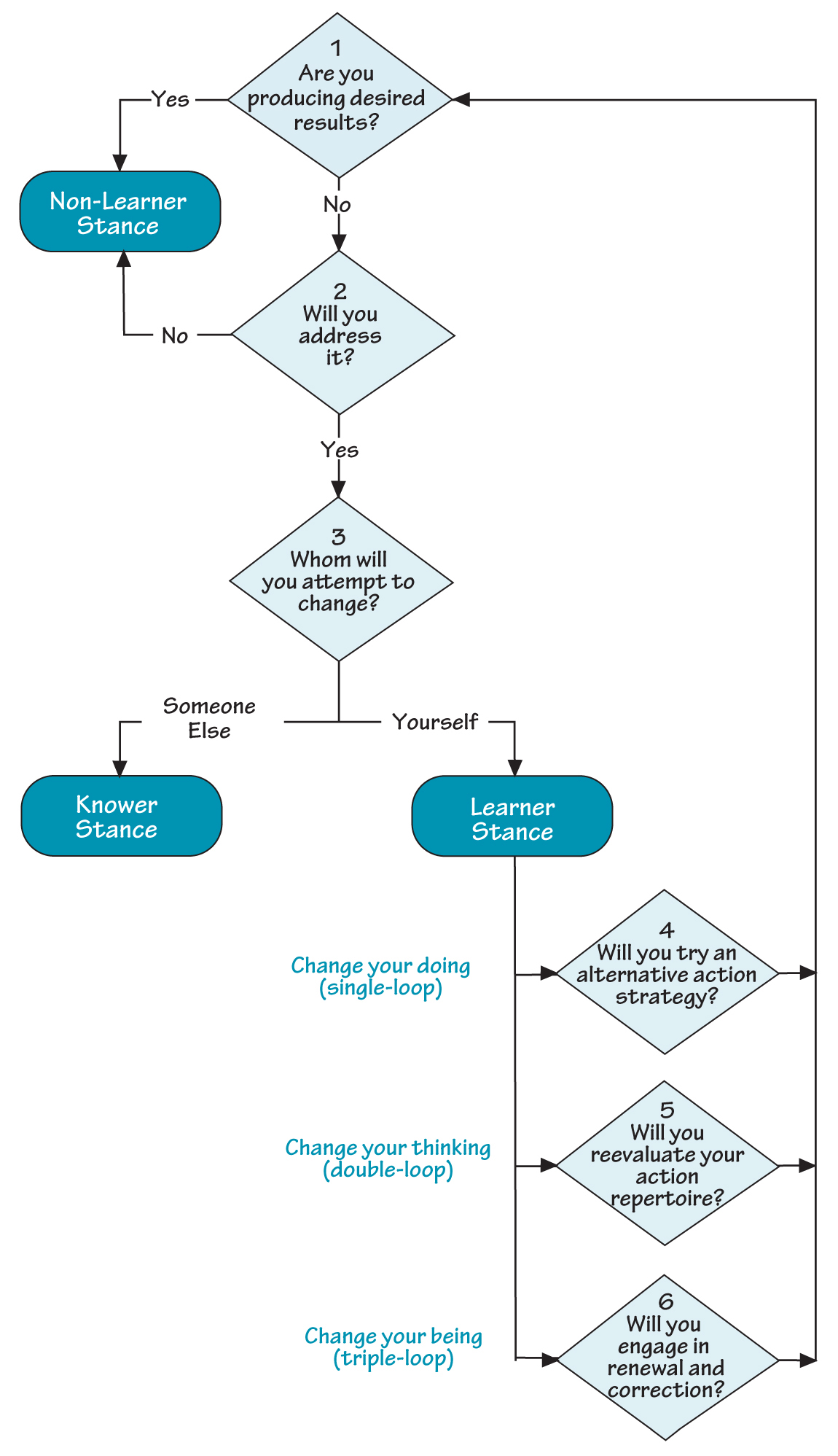

The Learner’s Path is a simple framework that walks a person along a decision tree, revealing a predisposition to operate either from a learner stance or from a knower stance. In order to operate from a learner stance, a person (or group) has to make three critical choices in succession:

(1) Admit that desired results are not being produced, (2) decide to take responsibility for addressing the less-than desired results, and (3) conclude that in order to achieve the desired results, they need to change themselves rather than change some other party. Once an individual has successfully answered these questions, they must next choose between three additional questions: Should I change my doing (question 4), my thinking (question 5), or my being (question 6)? A person’s answer depends on how deep they perceive the learning must be in order to achieve the desired results (the book, The Learner’s Path: Practices for Recovering Knowers, includes a more complete discussion of this process).

Walking the Learner’s Path

On January 20, 2009, Barack Obama became the 44th president of the United States. Let’s walk the Learner’s Path with him, as well as a few of his predecessors, using his inaugural address as a foretaste of whether he positions himself with a knower stance or a learner stance.

#1 Producing Desired Results?

Many presidents were quick to identify areas where the country is not achieving desired results. Some identified the problems as “out there” (, “I see one third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill nourished.” —Franklin Roosevelt, 1937), while others located the problems “in here” (, “There has been something crude and heartless and unfeeling in our haste to succeed and be great.” —Woodrow Wilson, 1913).

In his inaugural address, Barack Obama pointed out the problems plaguing America in both realms:, “That we are in the midst of crisis is now well understood. Our nation is at war against a far-reaching network of violence and hatred. Our economy is badly weakened, a consequence of greed and irresponsibility on the part of some, but also our collective failure to make hard choices and prepare the nation for a new age. Homes have been lost; jobs shed; businesses shuttered. Our health care is too costly; our schools fail too many; and each day brings further evidence that the ways we use energy strengthen our adversaries and threaten our planet.”

#2 Will You Address It?

Every president advocates for addressing the woes of the country or world—I cannot find an exception to this rule. Even Warren G. Harding and James Buchanan, frequently cited as two of the worst presidents, spoke of wanting to take responsibility for something. Harding’s aspirations were less-than-inspiring: “I speak for administrative efficiency, for lightened tax burdens, for sound commercial practices, for adequate credit facilities, for sympathetic concern for all agricultural problems, for the omission of unnecessary interference of Government with business, for an end to Government’s experiment in business, and for more efficient business in Government administration.” And Buchanan, “a man John F. Kennedy once aptly described as ‘cringing in the White House, afraid to move,’ while the nation teetered on the brink of civil war,” spent 14 percent of his speech expounding the virtues of constructing a military road (quote from Jill Lepore, “The Speech: Have Inaugural Addresses Been Getting Worse?” The New Yorker, January 12, 2009).

Obama wasted no words in asserting that the lack of desired results was unmistakably his to address:, “Today I say to you that the challenges we face are real. They are serious and they are many. They will not be met easily or in a short span of time. But know this, America—they will be met.”

#3 Whom Will You Attempt to Change?

Plenty of presidents have blamed various offenders for the problems the nation faces. Some do so quite succinctly: “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem” (Ronald Reagan, 1981). Others have been more verbose, but no less vehement: “The rulers of the exchange of mankind’s goods have failed, through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence. … Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men” (Franklin Roosevelt, 1933). Still others use a more subtle way of blaming their targets: “We shall do our share in defending peace and freedom in the world. But we shall expect others to do their share. … Just as we respect the right of each nation to determine its own future, we also recognize the responsibility of each nation to secure its own future. Just as America’s role is indispensable in preserving the world’s peace, so is each nation’s role indispensable in preserving its own peace” (Richard Nixon 1973).

But let me point out an important distinction. There is a difference between naming who you think caused the problem and who needs to change so that a solution takes hold. Roosevelt went on to say, “The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.” He is calling for the nation to address this crisis by changing itself—by adopting a higher set of values, rather than merely driving the money changers from the temple, or making them change their ways. Reagan, too, expected the American people to change themselves in order to address the problem. He didn’t expect the government to change itself:, “We are a nation that has a government— not the other way around. Our government has no power except that granted it by the people. It is time to check and reverse the growth of government.”

Nixon, on the other hand, continued with the veiled indictment that “they” should change, rather than “we.” He goes on to say, “Let us encourage individuals at home and nations abroad to do more for themselves, to decide more for themselves. Let us locate responsibility in more places. Let us measure what we will do for others by what they will do for themselves.”

President Obama’s message that we ourselves must change comes through loud and clear in several passages, including:, “But our time of standing pat, of protecting narrow interests and putting off unpleasant decisions—that time has surely passed. Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America.” Having successfully answered the first three questions above, Obama is clearly adopting a learner stance.

So, what kind of learning does he call the American people to attempt? He calls for learning and change at all three levels: doing new things, thinking new thoughts, and being new people.

#4 Change Your Doing

“For everywhere we look, there is work to be done. … We will build the roads and bridges … restore science to its rightful place … raise health care’s quality and lower its cost. We will harness the sun and the winds and the soil …. We will transform our schools and colleges and universities …. All this we can do. All this we will do.” In this sample, Obama is calling the people to action—to do new things. He is not asking us to rethink anything or be anyone different than who we are—he is simply challenging us to get busy.

#5 Change Your Thinking

Obama also challenges the people to think differently about things. This, in turn, will lead to new actions. For example, in an obvious reference to Reagan’s first inaugural address (, “It is no coincidence that our present troubles … result from unnecessary and excessive growth of government”), he challenges the people to rethink the role of government:, “The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works—whether it helps families find jobs at a decent wage, care they can afford, a retirement that is dignified.” The implication is that once we have this new understanding of government, we can get busy changing government to stimulate jobs, healthcare, and retirement.

#6 Change Your Being

And, finally, with images of a journey that must be recommenced and principles that must be reaffirmed, the president calls Americans to be a different, more mature people. “We remain a young nation, but in the words of Scripture, the time has come to set aside childish things. The time has come to reaffirm our enduring spirit; to choose our better history; to carry forward that precious gift, that noble idea, passed on from generation to generation: the God-given promise that all are equal, all are free, and all deserve a chance to pursue their full measure of happiness.”

The Critical Distinction

The critical distinction between knowers and learners is that learners are willing to change themselves, while knowers expect others to change for them to be able to achieve their desired results. Knowers may make short-term progress by cajoling others into changing while remaining unchanged themselves, but for long term, sustainable results, a person, or a people, must change themselves—thus overcoming changing circumstances with a greater ability to respond.

Knower Stance. As suggested earlier, Nixon’s second inaugural address seemed to have numerous allusions, such as, “we shall expect others to do their share,” which suggest that other countries and other people must change to “make life better in America.” This is the classic sign of a knower.

The American people must now make our own choice—will we be learners or knowers?

James Buchanan appears to have the marks, not so much of a knower, but of a non-learner. On the question of slavery and the threatened succession of the southern states, he seemingly tried to wish it away:, “May we not, then, hope that the long agitation on this subject is approaching its end, and that the geographical parties to which it has given birth … will speedily become extinct? Most happy will it be for the country when the public mind shall be diverted from this question to others of more pressing and practical importance.”

Warren G. Harding’s inaugural speech is a tepid homage to American distinction and status quo. Numerous passages like this one make the point: “We aspire to a high place in the moral leadership of civilization, and we hold a maintained America, the proven Republic, the unshaken temple of representative democracy, to be not only an inspiration and example, but the highest agency of strengthening good will and promoting accord on both continents.” An attitude of superiority and not rocking the boat gives evidence of knower tendencies. Harding’s lack of success in office suggests that preserving one’s own realm is a sure way to ineffectiveness.

Learner Stance. In each of Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural speeches, he appealed to both sides of the civil division to consider new actions, new attitudes, and a new sense of who they are—calling on the “better angels of our nature.” This learner stance is illustrated well in the following passage from his first address:, “My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well upon this whole subject. … Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him who has never yet forsaken this favored land are still competent to adjust in the best way all our present difficulty.” History will concur that this learning perspective served our country well and made him, arguably, the most important, effective, and honored president in American history.

So, with it similarly established that President Obama has begun his term in office with a glimpse of a learner stance, the American people must now make our own choice—will we be learners or knowers? He has called us to a higher stance of responsibility, hope, and unity of purpose. Will we choose our “better history?” How will we, as well as Obama himself, respond to his final challenge:, “Let it be said by our children’s children that when we were tested we refused to let this journey end, that we did not turn back nor did we falter; and with eyes fixed on the horizon and God’s grace upon us, we carried forth that great gift of freedom and delivered it safely to future generations.” Time will tell.

Brian Hinken is the Director of Learning and Renewal for Gerber Memorial Health Services in Fremont, Michigan. He is the author of The Learner’s Path: Practices for Recovering Knowers (Pegasus Communications, 2007) and the newly published pocket guide, The Learner’s Path: Moving from Knower to Learner.