In the summer of 2006, a group of local foundations supported the leaders of Calhoun County Michigan (population 100,000), in developing a 10-year plan to end homelessness (David Stroh and Michael Goodman, “A systemic approach to ending homelessness,” Applied Systems Thinking Journal, Topical Issues No. 4). The agreement forged by government officials at the municipal, state, and federal levels – along with business leaders, service providers, and homeless people themselves – came after years of leadership inertia and conflict regarding what needed to be done to solve the problem. Moreover, the plan signaled a paradigmatic shift in how the community viewed the role of temporary shelters and other emergency response services. Rather than see them as part of the solution to homelessness, people came to view these programs as one of the key obstacles to ending it.

The plan won state funding, and a new executive director supported by a multi-sector board began steering implementation. Service providers who had previously worked independently and competed for foundation and public monies came together in new ways. One dramatic example was that they all voted unanimously to reallocate HUD funding from one service provider’s transitional housing program to a permanent supportive housing program run by another provider. Jennifer Schrand, who chaired the planning process and is currently Manager of Outreach and Development for Legal Services of South Central Michigan, observed, “I learned the difference between changing a particular system and leading systemic change.”

TEAM TIP

Muster the courage to ask different kinds of questions, such as, “What are we willing to give up in order for the system as a whole to succeed?”

Calhoun County has done a remarkable job of securing permanent housing for the homeless, especially in the face of the economic downturn. For example, in the plan’s first three years of operation from 2007-2009, homelessness decreased by 13% (from 1,658 to 1,437), and eviction rates declined by 3%, despite a 70% increase in unemployment and 15% increase in bankruptcy filings. Readers can follow the ongoing progress of the initiative at the Coordinating Council of Calhoun County website.

Why was this intervention so successful when many other attempts to improve the quality of people’s lives fall short? For example, urban renewal programs of the 1960s were backed by good intentions and significant funding, yet they failed to produce the changes envisioned for them. Moreover, the programs often made living conditions worse – leading to outcomes such as abandoned public housing projects and increased unemployment that resulted from what appeared to be successful job training programs (see Jay W. Forrester, Urban Dynamics, 1969).

Stories of well-intentioned yet counterproductive solutions abound, as we learn that food aid can lead to increased starvation by undermining local agriculture, and drug busts can cause a rise in drug-related crime by reducing the availability and increasing the price of the diminished street supply. In other cases, short-term successes frequently fail to be sustained, and the problem mysteriously reappears. We see this dynamic when civic leaders invest in programs to reduce urban youth crime only to have the crime rate subsequently rise, or when international donors fund the drilling of wells in African villages to improve access to potable water, with the result that the wells eventually break down and villagers are unable to fix them.

By applying a systems thinking-based approach, the project to end homelessness managed to overcome the pitfalls of these other initiatives. The partners combined two significant interventions:

- a proactive community development effort that engaged leaders in various sectors along with homeless people themselves, and

- a systems diagnosis that enabled all stakeholders to agree on a shared picture of why homelessness persists and where the leverage exists in ending it.

In other words, the approach combined more conventional processes that facilitate acting systemically with tools to help the stakeholders transcend their immediate self-interests by thinking systemically as well.

Likewise, a comprehensive initiative to improve food and fitness – and in the process address childhood obesity – illustrates how the application of systems thinking can help organizations make better decisions about how to use their limited resources for highest sustainable impact (much of the first part of this article was adapted from David Peter Stroh, “Leveraging Grant-Making: Understanding the Dynamics of Complex Social Systems,” Foundation Review, Vol. 1, No. 3).

The Non-Obvious Nature of Complex Systems

Lewis Thomas, the award-winning medical essayist, observed, “When you are confronted by any complex social system… with things about it that you’re dissatisfied with and anxious to fix, you cannot just step in and set about fixing with much hope of helping. This is one of the sore discouragements of our time” (The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher, 1979). The stories above about failed interventions epitomize this poignant insight. They share other specific characteristics:

- The solutions that were implemented seemed obvious at the time and in fact often helped achieve the desired results in the short term. For example, it is natural to provide shelter, even temporary, for people who are homeless.

- In the long term, the intervention neutralized short-term gains or even made things worse. For example, the temporary shelters provided by Calhoun County led to the ironic consequence of reducing the visibility of its homeless population, which diminished community pressure to solve the problem permanently.

- The negative consequences of these solutions were unintentional; everyone did the best they could with what they knew at the time.

- When the problem recurs, people fail to see their responsibility for the recurrence and blame others for the failure.

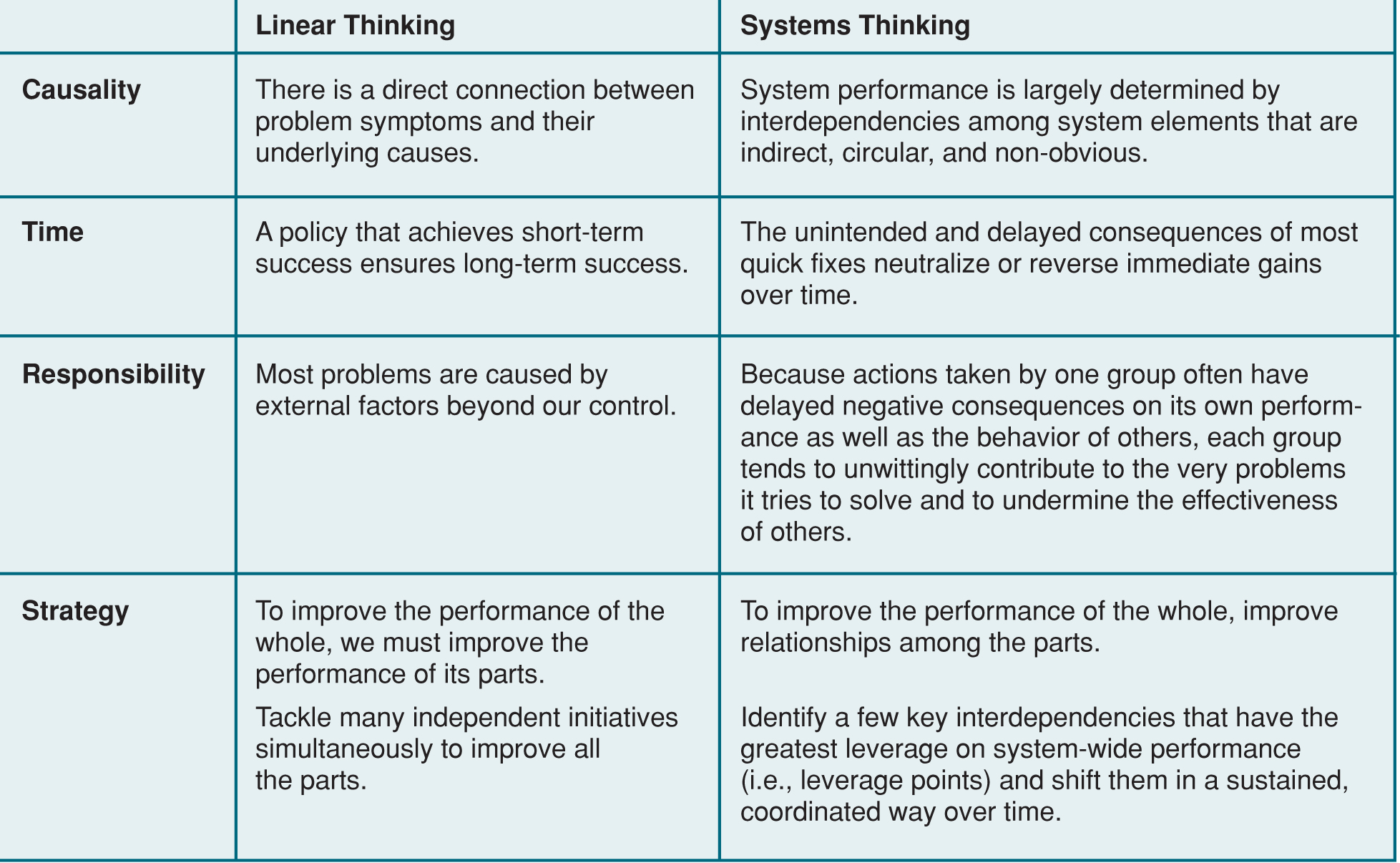

How can the interactions over time among elements in a complex system transform the best of intentions into such disappointing results? The reason lies in part in our tendency to apply linear thinking to complex, nonlinear problems. Systems and linear thinking differ in several important respects, as shown in “Distinguishing Linear Thinking from Systems Thinking.”

For instance, a linear approach to starvation might lead donors to assume that sending food aid solves the problem. However, thinking about it in a systemic way would raise concerns about such unintended consequences as depressed local food prices that deter local agricultural development and leave a country even more vulnerable to food shortages in the future. From a systemic view, temporary food aid only exacerbates the problem in the long run unless it is coupled with supports for local agriculture.

DISTINGUISHING LINEAR THINKING FROM SYSTEMS THINKING

Systems vs. Linear Thinking

Because the problems addressed by many organizations are exceedingly complex, one step they can take to increase the social return on their investments is to think systemically (vs. linearly). Implementing a systems approach involves the following process:

- Building a strong foundation for change by engaging multiple stakeholders to identify an initial vision and picture of current reality

- Engaging stakeholders to explain their often competing views of why a chronic, complex problem persists despite people’s best efforts to solve it

- Integrating the diverse perspectives into a map that provides a more complete picture of the system and root causes of the problem

- Supporting people to see how their well-intended efforts to solve the problem often make the problem worse

- Committing to a compelling vision of the future and supportive strategies that can lead to sustainable, system-wide change

Based on the insight that non-obvious system dynamics often seduce us into doing what is expedient but ultimately ineffective, the Food and Fitness (F&F) initiative of the W. K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) followed these steps in taking a comprehensive systems approach to planning, implementing, and evaluating the program. Initial planning began in 2004, and the first work with systems thinking in the field started in 2007. Implementation continues today in nine communities throughout the U. S.

F&F began as a response to staff and board member concerns about the rising rate of childhood obesity and early onset of related diseases such as type 2 diabetes. The WKKF program officers who initially led F&F, Linda Jo Doctor and Gail Imig, knew that many well-intentioned programs had attempted to address childhood obesity by focusing on nutrition, education, or exercise. Some targeted policy change, whereas others focused on individual behavior, but data clearly showed undesirable outcomes continuing, especially among children from poor families.

WKKF had long supported developing a healthy, safe food supply and increasing consumption of good food. Because the issue was highly complex and prior efforts to address it had been unsuccessful, the program officers determined that a systemic approach would be essential to achieving long-term goals. They believed that applying this kind of process to F&F would increase the likelihood of engaging a diverse group of people and organizations, fostering collaboration and finding innovative strategies to change the underlying systems, and thereby creating and sustaining the healthy results everyone seeks for children and families.

Applying Systems Thinking to Program Planning

Of the three major programming functions – planning, implementation, and evaluation – systems thinking can play an especially important role in improving planning. Here are suggestions for how to integrate these steps into the program planning process.

Step 1: Build a Foundation for Change

Building a strong foundation for systemic change involves engaging diverse stakeholders in the planning stage. This is a cornerstone of the F&F initiative. WKKF developed its knowledge base by bringing together researchers and theorists from around the country in fields such as public health, nutrition, exercise physiology, education, behavior change, child development, social change, and social marketing. The foundation also assembled a group of community thought leaders for a conversation about the current realities in their communities, as well as their visions for communities that would support the health of vulnerable children and families. In addition, WKKF engaged with other foundations throughout the U. S. in conversations about their collective thinking on childhood obesity and the roles foundations might play. From all of this outreach, a collective vision for the initiative began to emerge—not as a reaction to the immediate circumstances, but from an enriched understanding of current realities, as well as deeply shared aspirations for the future:

We envision vibrant communities where everyone – especially the most vulnerable children – has equitable access to affordable, healthy, locally grown food, and safe and inviting places for physical activity and play.

Step 2: Engage Stakeholders to Explain Often Competing Views

Building on the results of Step 1 above, systems mapping is one tool to help stakeholders see how their efforts are connected and where their views differ. This tool extends the more familiar approaches of sociograms or network maps to show not only who is related to whom, but also how their different assessments of what is important interact.

F&F’s conversation among community thought leaders was structured using the systems thinking iceberg model. Examples of questions included, “What is happening now regarding the health and fitness of children in your communities that has been capturing your attention?” “What are some patterns related to health and fitness of children that you’re noticing?” “What policies, community or societal structures, and systems in your communities do you believe are creating the patterns and events you’ve been noticing?” “What beliefs and assumptions that people hold are getting in the way of children’s health and fitness?” This conversation ended with the question, “What is the future for supporting the health of children and their parents that you truly care about creating in your community?”

Initially, each participant’s comments reflected his or her own work and the competition for resources that typically accompanies community engagement. Some believed the lack of mandated daily physical education caused childhood obesity. Others faulted school lunches. Some hoped parents would prepare more meals at home rather than eating out. Several blamed the rise of fast-food establishments. In the ensuing conversation, participants began to consider one another’s thinking. They came to realize that no single explanation, including their own, could fully explain the health outcomes they saw. The conversation revealed different perspectives and experiences but also began aligning participants around common beliefs and a deeper, broader understanding of the issue.

Step 3: Integrate Diverse Perspectives

Systems maps integrate diverse perspectives into a picture of the system and provide an understanding of a problem’s root causes. Participants in F&F came to see that the obesity epidemic in children was the result of national, state, and local systems failing to support healthy living, rather than a consequence of accumulated individual behaviors. They began to recognize the interrelationships among systems such as the food system, the quality of food in schools and neighborhoods, the natural and built environment and its role in supporting active living, safety, and public policy such as zoning. They also started to understand how individual organizations’ good intentions and actions could actually undermine one another’s efforts. These conversations paved the way for collaboratively creating strategies and tactics in later phases of the work.

Step 4: Support Responsibility for Unintended Consequences

One characteristic of social systems is that people often unintentionally contribute to the very problems they want to solve. Systems thinking enabled communities working in the F&F initiative to uncover potential unintended consequences of their efforts.

For example, marketing the concept of eating locally grown food without developing a food system that can provide it can lead to increased prices for that food, putting it out of reach for schools, children, and families in low-income communities and thus decreasing the consumption of good food among that population. Pushing for policies to allow open space to be used for community gardens could have the unintended consequence of reducing access to outdoor areas for children to play and be active.

If people understand how they contribute to a problem, they have more control over solving it. Raising awareness of responsibility without invoking blame and defensiveness takes skill – yet it is well worth the effort.

Step 5: Commit to a Compelling Vision and Develop Strategies

Once a foundation for change has been developed and the collective understanding of current reality has deepened, the last planning step is to affirm a compelling vision of the future and design strategies that can lead to sustainable, system-wide change. This step entails

- committing to a compelling vision,

- developing and articulating a theory of change,

- linking investments to an integrated theory of change, and

- planning for a funding stream over time that mirrors and facilitates a natural pattern of exponential growth (for details about each of these processes, see David Peter Stroh and Kathleen Zurcher, “Leveraging Grant-Making—Part 2: Aligning Programmatic Approaches with Complex System Dynamics,” Foundation Review, Vol. 1, No.4).

The systems approach to this work resulted in unanticipated positive consequences. Developing relationships, engaging in high-quality conversations, and committing to a common vision during the planning phase produced immediate results in many of the communities. In Northeast Iowa, Luther College, the public school district in Decorah, and the city council created a proposed community recreation plan under which Luther College would grant a no-cost lease on 50 acres of land for a citywide sports center and would raise the money to build an indoor aquatic center; the city would build soccer and tennis courts; and the school district would raise money for maintenance. Documenting these results during each phase of work is critical to maintaining momentum and funding for long-term system change.

A Pause on the Quick Fix

Our continued work in applying systems thinking to social change in such areas as homelessness, early childhood development, K-12 education, and public health affirms the importance of integrating approaches for acting and thinking systemically. Many people have become familiar with tools such as stakeholder mapping and community building, and methodologies for getting the whole system in the room to bring together the range of interests and resources vital to social change. These are positive steps toward overcoming the pitfalls of the failed interventions referenced at the beginning of the article.

However, unless we drastically shift the way we think, bringing diverse stakeholders together all too often fails to surface or reconcile the differences between people’s espoused (and sincere) commitment to serving the most vulnerable members of society and the equally if not more powerful competing commitment to optimizing their individual contributions and maintaining their current practices. For example, shelter directors want to end homelessness, but they actually get paid according to the number of beds they fill each night. Donors want to end homelessness, but their benefactors get more immediate satisfaction from housing people temporarily. Service providers who specialize in helping the homeless may find themselves competing for funds that might otherwise be allocated toward prevention.

As one nonprofit noted, the greatest challenge in creating social change can be mustering the courage to ask different kinds of questions, such as, “What is our organization willing to give up in order for the system as a whole to succeed?” Thinking systemically helps people answer that question in a way that serves their higher intentions. It does so by enabling them to see the differences between the short and long-term impacts of their actions, and the unintended consequences of their actions, on not only other stakeholders but also themselves. The result might be that one shelter director decides to close his facility, while another reinvents her organization to focus on helping the homeless build bridges toward the safe, permanent, affordable, and supportive housing they ultimately need to heal. The net outcome is that people act in service of the whole because it naturally follows their thinking about how the whole behaves.

Ann Mansfield, co-director of the F&F program in Northeast Iowa, summarized the benefit of using systems thinking: “The tools helped us put a pause on the quick fix.” Systems thinking provides frameworks and tools that can enhance organizations’ efforts to achieve lasting systems change results by making a few key coordinated changes over time. By following the five-step change process for achieving sustainable, system-wide improvement as spelled out in this article, we can increase the chances that our interventions will have the results we fervently desire.

A SHARED VISION OF ENDING HOMELESSNESS

In Calhoun County, Michigan, the local Homeless Coalition had been meeting for many years to end homelessness. Their shared desire to serve the homeless had been undermined by disagreements about alternative solutions, competition for limited funds, and limited knowledge about best practices. Although many understood the importance of a collective effort to provide critical services, housing, and jobs to both homeless people and those at risk of losing their homes, they were unable to generate the collective will and capacity to implement such an approach. Finally, the promise of state funding if they could agree on a 10-year plan to end homelessness, the provision of funding for developing the plan by local donors, and the use of a team of consultants experienced in community development, systems thinking, and national best housing practices enabled them to break through years of frustrated attempts.

With the help of consultants David Stroh, Michael Goodman, and Alexander Resources Consulting, the Coalition enlisted and organized the support of community leaders along with representatives from the homeless population. They established a set of committees and task forces as well as a clear and detailed planning process. While they began by articulating a shared vision of ending homelessness, they would not be able to really commit to this result until they fully understood the system dynamics that perpetuated the problem.

The consultants led the group in applying systems thinking to (1) understand the dynamics of local homelessness, (2) determine why the problem persisted despite people’s best efforts to solve it, and (3) identify high-leverage interventions that could shift these dynamics and serve as the basis for a 10-year plan. Through interviews with all key stakeholders, they analyzed a number of interdependent factors that led people to become homeless in the first place, get off the street temporarily, and find it so difficult to secure safe, supportive, and affordable permanent housing.

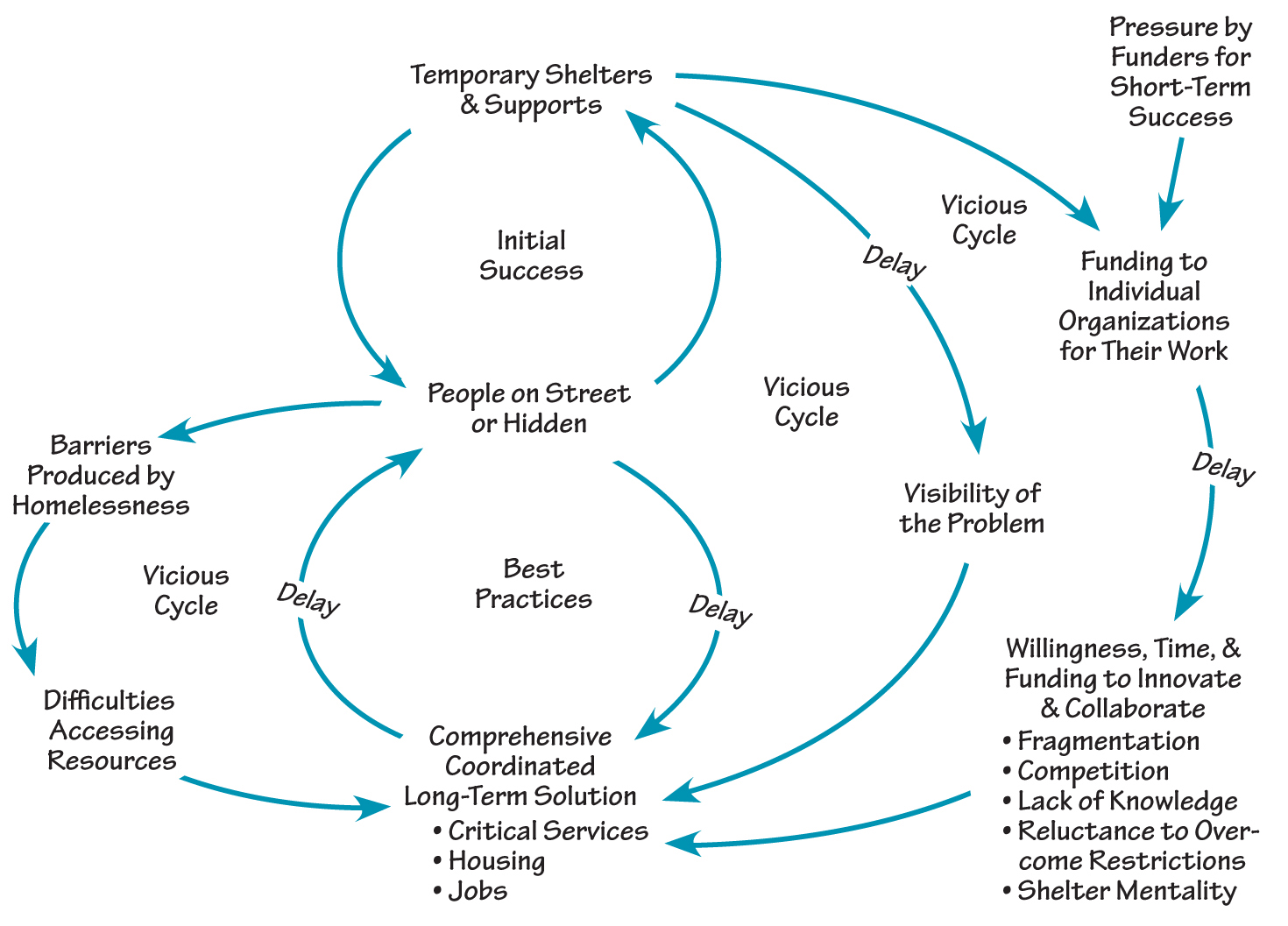

We learned that the most ironic obstacle to implementing the fundamental solution was the community’s very success in providing temporary shelters and supports – an example of the “Shifting the Burden” systems archetype (“Shifting the Burden to Temporary Shelters”). These shelters and supports had led to several unintended consequences. One was that they reduced the visibility of the problem by removing homeless people from public view. The overall lack of visibility reduced community pressure to solve the problem and create a different future.

The temporary success of shelters and other provisional supports also tended to reinforce funding to individual organizations for their current work. Donors played a role in buttressing existing funding patterns through their pressure to demonstrate short-term success. Such reinforcement decreased the service providers’ willingness, time, and funding to innovate and collaborate. The community’s collective ability to implement the fundamental solution was undermined as a result.

In response to this insight, the consulting team helped the county define goals that formed the basis for a 10-year plan subsequently approved by the state:

- Challenge the shelter mentality and end funding for more shelters.

- Develop a community vision where all citizens have permanent, safe, affordable, and supportive housing.

- Align the strategies and resources of all stakeholders, including funders, in service of this vision.

- Redesign shelter and provisional support programs to provide more effective bridges to critical services, housing, and employment.

Today, the county continues to make progress toward these goals. The program has an executive director, in-kind funding for space and supplies, additional funding focused on long-term strategies, and a community-wide board supported by eight committees with clear charters producing monthly reports on their goals. A community-wide eviction prevention policy was changed to enable people to stay in their homes longer, and a street outreach program is going well to place people into housing.

SHIFTING THE BURDEN TO TEMPORARY SHELTERS

David Peter Stroh, Master’s Degree, City Planning, was a founding partner of Innovation Associates. He is currently a principal with Bridgeway Partners, an organizational consulting firm dedicated to supporting social change through the application of organizational learning disciplines. dstroh@bridgewaypartners.com

Kathleen A. Zurcher, PhD, Educational Psychology, partners with communities and organizations to achieve their desired future by applying and building capabilities in organizational learning and systems thinking. In 2008 she retired from WKKF. She was previously a senior administrator for Family Medicine, and a faculty member in the University of Minnesota’s extension service and at Lehigh University. kzurcher33@gmail.com