The successful entrepreneurial journey lies at the heart of the American dream. Historically, Americans have had a romance with those who, in the words of Horatio Alger, combine “pluck and luck” to travel the road from “rags to riches.” This journey represents the triumph of merit and virtue over inherited wealth. It allows every man — and now every woman — to become a king or a queen in a democratic society.

Over the last century, people such as Ford, Rockefeller, and Carnegie have been our entrepreneurial icons. Today, Gates, Bezos, and the founders of many thousands of dot.com startups fill the newspapers and our imagination. This dream of creating something new and, in the process, engendering wealth, power, and prestige has spread around the globe. New businesses are proliferating in the Pacific Rim, South America, the Middle East, and Europe — places that, not so long ago, were marked by rigid class and economic systems that discouraged entrepreneurial effort.

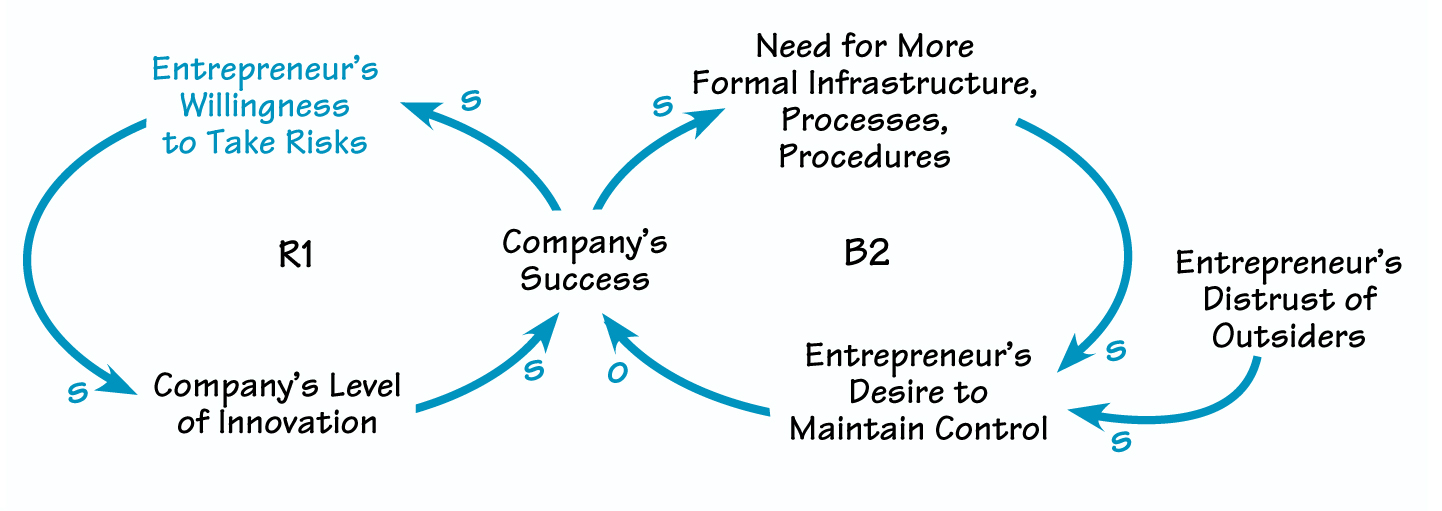

The entrepreneurial journey, however, is rarely straight or easy. And success, once achieved, is not always what the company’s founders anticipated. As a business grows in size and complexity, it becomes harder for them to manage in the informal, family-like ways that led to early success. Leaders face a paradox: In order to manage and continue growth, more effective control requires letting go. That is, entrepreneurs need to entrust others to manage much of the organization and to institute systems, such as budgets and quality control, that partly replace or supplement their vigilance. Then, once effective business processes have been introduced, the organization must find ways to reinfuse itself with the spontaneous, creative energies of the start-up days to avoid growing stagnant and dry. In the most successful companies, this cycle, from entrepreneurial to professional and back to entrepreneurial, may repeat many times over.

The entrepreneurial journey is rarely straight or easy. Leaders face a paradox: In order to manage and continue growth, more effective control requires letting go.

In other words, successful entrepreneurs — those who build, sustain, and continuously renew their businesses — must learn to balance risk taking, hard work, and self-reliance with forethought, delegating authority, and trusting their staff. The same is true for entrepreneurial endeavors in large, otherwise bureaucratic organizations. This uncommon balance of entrepreneurial and professional leadership is hard to achieve. No wonder so many entrepreneurs cannot complete their journey: 50 percent of start-ups are out of business after the first year; 80 percent close by their third year.

For all but the most talented (and lucky), the tricky process of integrating entrepreneurial with professional leadership requires meeting certain challenges and acquiring new practices. It means a major shift in “business as usual” for everyone in the company. Although no single approach to change can accommodate every entrepreneurial culture, most entrepreneurs — and those who work for them — will recognize their own experiences and the efficacy of many of the recommended action steps in the transition process outlined below.

The Entrepreneurial Personality

The entrepreneurs’ personality drives and shapes the organizations that they build. On the upside, people who launch start-ups generally possess high energy and enthusiasm, enjoy building things, have enormous reserves of creativity and intuition, and live for excitement and challenges. They are visionaries who rarely stay focused on the small things in life but try to change the world in some substantial way. And they are willing to assume responsibility for almost everything that happens in their organization; take frequent, calculated risks; and persevere in the face of great odds and almost constant pressure. Through their actions, drive, purposefulness, and decisiveness, entrepreneurs inspire effort and loyalty in others.

On the downside, entrepreneurs can be arrogant, impulsive, distrustful, and controlling. They often think they can do the job better than anybody else, yet they dislike doing routine tasks. Entrepreneurs prefer initiating and developing projects, not running them — but they want to be in charge of every aspect of the organization. These contrary qualities, left unchecked, eventually isolate the company’s founders, cutting them off from the information and people who have been the organization’s lifeblood.

In the early days of most startups, profit often takes a backseat to growth. Planning tends to be ad hoc.

THE LIMITS TO ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Budgets and financial controls are almost absent. Training takes place on the job. Roles and responsibilities are defined by the tasks at hand, often shifting and overlapping one another.

In the short term, when organizations are small, they benefit from entrepreneurial qualities. For one thing, informality makes businesses agile and adaptive to market demands. For another, because the founders are clearly in charge — with power and prestige flowing directly from them and from those in close relationship with them — workers know who they’re accountable to. Plus, many employees, themselves caught up in the excitement and often given strong incentives, are willing to do whatever it takes to fulfill the entrepreneurs’ vision.

In the long term, however, problems tend to arise. The tight hierarchical structure of most start-ups inhibits the development and retention of strong managers and people’s capacity for autonomous action — especially when the entrepreneurial leaders can no longer devote time to the organization’s internal operations because they must work to position the company in the market. In addition, burnout and disillusionment run high in many employees, who sincerely try, but frequently fail, to maintain the entrepreneurs’ feverish pace and sense of unwavering commitment.

A Developmental Crisis

At some point in the life of every growing organization, ad hoc planning and determined, centralized leadership become inadequate for dealing with the complex tasks at hand. Signs of this inadequacy become evident when, for example, the company’s capacity to handle customer demands decreases, employees start missing key details such as order fulfillment, and the company burns venture capital faster than it builds products. Despite these clear warning signs, entrepreneurs and their management teams may not be ready to implement the processes that characterize professional management: careful planning; clearly defined roles and responsibilities; monitored budgets, financial performance, and product quality; and the entrusting of major responsibilities to someone other than the leadership team.

For a time chaos seems to reign. People feel confused and anxious about the company’s direction. Managers may be overwhelmed by the volume of work and the magnitude of their duties, but they feel they don’t have the time, budget, or expertise to hire the right support staff. So they fall into “fire-fighting” mode, trying to do everything themselves, partly because they don’t think their subordinates have the expertise or knowledge to do so, and partly because the company’s founders have modeled this kind of controlling behavior. This approach creates a “Limits to Success” scenario, in which the company’s incapacity to handle complexity limits its ability to grow (see “The Limits to Entrepreneurship”).

Even as they flounder, the leaders struggle to create an infrastructure that will help them meet the challenge of growth. But attempts to install processes such as information systems or budgets frequently fail: The entrepreneurs don’t yet have the skills to make them work or the habit of depending on them. Nor do they have the time — the demands of the present seem to conspire against their own long-term interests.

So just as the founders build the infrastructure, they tear it down again, relying on guts, determination, intuition, and even harder work. This method doesn’t succeed either, so they renew their efforts to institute policies and procedures. The entrepreneurs may go back and forth several times, in a maddening effort to escape their dilemma. Morale drops, and employee skepticism about the capacity of the management team to lead them through the crisis grows.

Here, then, is the fulcrum on which the developmental crisis turns: The organization must undergo fundamental change in order to survive, but few current employees are prepared or qualified to make the shift to a new operating mode — including the entrepreneurs. More often than not, only when the organization brings in a more professionally oriented leadership team does it survive — and, all too often, this move stems not from the entrepreneurs but, partly or entirely against their wishes, from a board of directors or venture capitalist.

Professional Leadership Organizations

In contrast with entrepreneurs, professional managers tend to be consistent, cautious, detail-oriented, and conservative in their personal styles. Yet, in their own way, they are far-seeing. Long-term planning, for instance, comprises a central part of their activity, as does the training and retention of able managers to guarantee the organization’s future. These leaders emphasize financial and product-quality controls that allow for course corrections when performance varies from goals. They also work to develop and maintain strong relationships with customers and suppliers. In short, professional managers create formal organizational structures, in which goals, operational processes, and roles and responsibilities are explicitly articulated, implemented, and monitored.

To begin to incorporate professional leadership into their organizations, entrepreneurial leaders must execute the following practices:

1. Delegate responsibility and authority. As organizations grow in size and complexity, the entrepreneurs must hire effective managers and trust them to do their jobs. To ensure a smooth transition, leaders should put this management team in place before launching major new initiatives.

2. Behave consistently. To some degree, entrepreneurs must curb their impulsive tendencies. Employees work better when they know what to expect in their jobs, what tasks they are responsible for, and how their performance will be evaluated. If entrepreneurs cannot limit their impulsiveness, they should hire an intermediary, such as a COO.

3. Plan and prioritize. Entrepreneurs, with input from managers and employees, need to set clear goals and priorities, even if it means letting go of some alluring tasks and opportunities. With this guidance, managers can effectively marshal organizational resources to accomplish the goals.

4. Communicate openly and effectively. Instead of keeping plans and financial data close to their vests, entrepreneurs need to share vital information with their staffs. Managers need this information to help plan and execute projects well.

5. Institute controls. Entrepreneurs must recognize the need to monitor key organizational processes, such as budgets and performance, and trust other people to do much of the oversight.

As crucial as it is for entrepreneurs to implement these professional practices in order for their companies to survive, most initially resist doing so. As we’ll see below, they and their staff are ill-equipped to handle the turbulence that arises as the company moves toward a new mode of operation.

Characteristics of Transition Periods

One of the major reasons that organizational transitions falter is that leaders do not anticipate and account for the uncertainty and difficulty that change brings to the entrepreneurial journey. Change rarely, if ever, follows a straight line, from conception to planning to realization. The process of managing change involves negotiating unexpected twists and turns, stops and starts, frustrating regressions and forward leaps of breathtaking speed and magnitude.

We can attribute this inability to navigate the change process in large part to the failure of our business culture to create an image of the journey that is both positive and realistic. So we continue to cling to the old idea that we can plan change step by step, and we become bewildered by the contradiction between this seductive myth and the tumultuous reality that we actually encounter.

The transition from entrepreneurial to professional leadership involves more than simply the development — or importation — of new skills and new processes. It also requires considerable physical, emotional, and intellectual stamina, as well as a capacity to move ahead with clear thinking and action in the face of inevitable uncertainty. Entrepreneurs who are leading their businesses to a mature level of development must be able to both fly with the waves of progress and endure stagnant times, and to let go of cherished ideas and often valued people, while promoting others who have not yet proven trustworthy.

We know that an entrepreneurial organization has completed the passage from old to new when it achieves a stable synthesis of its entrepreneurial origins and its professional future that fits its own distinctive purposes. This synthesis — merging creativity with controls — represents a new paradigm; that is, a new way for people in the organization to think, act, and feel that balances the best of the past and the promise of the future.

Developing a New Organizational Infrastructure

To integrate entrepreneurial leadership with professional management successfully, entrepreneurs and their organizations must move through four developmental stages.

1. Recognize the need for basic change. To begin the transition, the entrepreneurs, and then everyone else in the company, must perceive the need for change. Entrepreneurs generally understand why the organization must transform itself, but they often fail to act on this insight. Still believing that survival is paramount, they insist that they don’t have the time or resources to build a new infrastructure, hoping that small adjustments combined with determination and hard work — virtues that led to early success — will carry the day.

Entrepreneurs and their closest employees often cling to a culture that feels to some like family and to others like comrades waging war together against a hostile, uncomprehending world. At this stage discord may arise between the core group and formerly trusted lieutenants, who understand the risks to the organization if it doesn’t adopt a more professional infrastructure. It usually takes the financially oriented people, such as accountants and venture capitalists, to hammer home the need for implementing new systems and policies.

Once the entrepreneurs accept the inevitability of organizational transformation, the most effective way to convince other people in the company about the need for change is to create an environment where they can talk honestly about the challenges the organization is facing.

Action Items:

- Assemble a small transition management team that includes at least one employee who is not part of the entrepreneurs’ inner circle, one outsider (preferably a board member or an organizational development consultant), and the entrepreneurial leaders. Launching this process with a facilitated retreat can be helpful.

- Write a diagnosis that indicates current problems and reasons why the organization needs to change. Be sure to gather input from throughout the organization. You may want to introduce tools to support open discussion, especially if the organization’s culture has discouraged candid feedback in the past.

- • Identify areas of the company that have already changed or have been moving toward a professionally managed style and support these developments. You might want to provide workers in these areas with financial incentives, broaden their managerial roles, or publicize their accomplishments within the organization.

- Create informal dialogues at all levels of the organization about the company’s challenges and people’s fears around the change process. For example, at one company a manager instituted “Bagels with Steven,” a weekly meeting at which employees were allowed to vent frustration and confusion about the changes. Once employees felt their concerns were being taken seriously, they began to offer suggestions about the organization’s future path.

- Articulate a vision of what the organization might look like — and accomplish — in its new form.

2. Commit to and plan for change. Once the organization as a whole recognizes the need for transforming the company, everyone must commit to implementing a plan of action — even when present demands and financial risks are daunting.

Again, obstacles abound. In entrepreneurial organizations, the act of planning itself is problematic; it often violates the cultural norm. In response, leaders tend to hedge their bets: “Let’s do it, but I reserve the right to change course when I think it necessary.” Or they may languish in indecision, perhaps initiating change several times in small ways, then pulling back. Or the entrepreneurs may do an inadequate job of planning, saying “An hour or two should do the job. I know where we need to go, anyway.”

Entrepreneurs may also delegate the planning process to others and then override or limit their authority to implement the plan. This interference generally upsets the managers, who may engage in a struggle with the entrepreneurs for power. This process could have a positive outcome, by bringing the entrepreneurs’ ambivalence about the change process out in the open. Or it could cause the entrepreneurs to halt change efforts or alienate staff members.

Action Items:

- In consultation with the rest of the staff, identify any obstacles to change, including constraints on employees’ time, lack of material resources, and internal resistance to the initiative.

- Develop a plan to overcome these obstacles, and move the organization in the desired direction.

- Continue to support the people, teams, and processes in the organization that are already moving toward professional management, rather than focusing on correcting problems.

- Continue to hold dialogues, particularly with key personnel, to head off polarized situations. Bring ambivalence about change into the open by having people acknowledge their own doubts.

3. Implement the plan while tolerating instability. Once the organization is committed to the change process, everyone must execute the plan of action confidently, leaving little doubt about which direction the company is headed. For example, one key indicator of commitment is the entrepreneurs’ willingness to go outside of their circle of loyalists to hire and empower professional managers. These new leaders must possess the requisite skills to meet the organization’s needs — and may require higher levels of compensation than the existing pay scale supports.

Developing a new organizational infrastructure requires considerable time, energy, and skill. As change proceeds, anxiety in the organization will reach new heights, because key measures might get worse before they get better — customer complaints may jump, business may flag, and financial concerns may grow. These challenges will test everybody’s commitment to the plan. The leaders will probably spend many sleepless nights wondering what happened to their organization. Intense power struggles may emerge between the old and new guard of managers, or among members of each.

Initially, some employees may leave the company. Long-time workers may wonder if they will retain their jobs; others will develop a bunker mentality, determined to wait out the change “fad.” Many may feel betrayed by the entrepreneurs, who seem to have gone over to the “other side.” The professional managers, on the other hand, may feel the entrepreneurs are moving too slowly and sporadically.

In such trying times, the leaders and their close managers may be tempted to revert to old ways, once again seeking to micromanage every detail of the operation. Entrepreneurs may in fact respond to the instability by becoming dictatorial, uncertain, and indecisive, or by becoming dependent on a newly hired professional. Depending on their behavior at this time, the founders’ credibility might be seriously jeopardized.

The challenge for all is to tolerate the instability and the identity crisis — both the actual work disruptions and the mental and emotional responses to these disruptions. To do so, all employees must focus on maintaining a clear vision of what the changes can eventually do to help the company achieve it goals and appreciate the disruptions as natural “growing pains.”

Action Items:

- Develop a timeline that indicates when the company hopes to complete each aspect of the strategic plan. This timeline will help orient and reassure all the players that there is a solid plan for the future.

- Solicit the help of a coach or mentor — perhaps a board member who has successfully gone through the entrepreneurial process or a consultant—for moving through the transition.

- Provide guidance and training for loyal, long-time employees. Interview those outside the inner circle to see what they think of the changes. Reiterate and revise the change plan, making sure that each person can actually visualize their potential career path in the new structure.

- Continue to converse with employees, recognizing how change brings loss and regrets, and help make these feelings acceptable. Identify and discuss areas of instability, doubt, and tension until they are resolved or modulated.

4. Integrate the old and the new.

The final developmental challenge is to retain the entrepreneurial spirit in the new and improved organization. Often, in the name of efficiency and order, organizations kill off the sense of adventure that built them. But that energy is what allows companies to remain innovative and stay on the cutting edge of their industries. After the transition, the business must still compete in fast and constantly changing markets and technologies; if it grows sluggish, officious, and conservative — in short, bureaucratic — it will fail to remain competitive.

To that end, the new management systems need to act in the service of the entrepreneurial spirit. The organization needs to continually find ways to integrate the best of the old and the new, and to stabilize itself around this integrated way of doing business. For the leaders, the challenge is giving the management team room to exercise their skills and stabilize the organization while, at the same time, providing them with vision and support.

The organization needs to continually find ways to integrate the best of the old and the new.

The alternative to integration is both conflict — between those who represent the entrepreneurial style and those who advocate planning and controls — and fragmentation — in which various departments and people operate in contradictory, disjointed ways. Each group believes it understands more fully than others the strategy that the company needs to follow. Factions can fall into a kind of cold war, an unstable form of stability that creates constant tension and undermines performance.

Action Items:

- Identify and measure the value of what is “old” (flexibility, creativity) and what is “new” (infrastructure, controls). Outline how the company will synthesize the best of both to create something more effective than either style.

- Continue to define and redefine how the organizational plan will allow the company to move forward to meet the demands of growth, competition, quality, and so forth. In order to adapt all employees and tasks into the new organization, the plan needs to be flexible and responsive to new ideas and unintended consequences.

- Introduce methods to sustain openness, flexibility, and creativity, such as continuous learning and scenario planning. Create or maintain entrepreneurial aspects of the organization through equity and profit-sharing practices and spinning off new products into new companies or divisions.

- Create new roles for entrepreneurs who want to remain engaged with their companies in a different capacity, so they can still provide overarching vision and leadership. In order to satisfy their need for action, create opportunities for entrepreneurs to take on special projects, such as leading a major product development process.

Realizing the Dream

In summary, if entrepreneurs want to create a lasting enterprise that impacts their industries well into the future, they need to lead their organizations in making the transition from a startup to a professional culture. By integrating professional leadership (effective planning, budgets, and quality control) with the entrepreneurial spirit (openness, flexibility, and the ability to think “outside of the box”), organizations can continuously renew themselves and achieve long-term, sustained success.

Barry Dym, Ph. D., is president of WorkWise Research & Consulting. He has 30 years of experience as an entrepreneur, organizational development consultant, author, teacher and psychotherapist.

NEXT STEPS

- Identify areas in your company that have grown through entrepreneurial efforts but lack an infrastructure to monitor and sustain growth. How might you integrate professional leadership into these areas?

- Notice where there is resistance to change in your organization, particularly in situations where more formal planning and controls are needed to accomplish organizational goals. What structures are in place to make people comfortable with the change process? How might you create those structures if they aren’t currently available?

- Find colleagues who have been moving toward a professionally managed style. In what ways can you work together to support each other’s efforts?