In the streets of Seattle, Washington, last year, the world witnessed a striking expression of social concern. An array of highly disparate groups — from small business representatives to Green Party environmentalists, from teachers to animal rights groups — gathered to protest actions by the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO, a body responsible for shaping the boundaries of transnational commerce, drew fire for its perceived alliance with corporations and their push toward unfettered globalization. These demonstrations were unusual not only because of the diversity of the protestors, but also because of the ultimate target of their ire: the modern, global “megacorporation.” The protestors named these companies as major contributors to many of the world’s ills — including defoliation of rainforests, hostilities in Third World nations, and inadequate healthcare distribution in the West.

Right or wrong, the Seattle protests highlighted the widespread influence that corporations exert on people’s lives today. As social institutions, companies have an unprecedented impact on individuals, families, communities, nations, and the planet itself. For instance, who among us does not struggle with the challenge of balancing family and work life? Who among us may not someday benefit from biotechnology breakthroughs? Who among us is not concerned about the impact of manufacturing waste on the environment? Who among us does not take advantage of cheap and reliable telecommunications? The pure size, scope, and transnational nature of the modern corporation have given it a unique — and growing — role in our daily lives.

A Tool for Corporate “Response-ability”

With this level of influence come new demands for responsibility, as the demonstrations in Seattle showed. Simply put, the more impact that corporations have on people’s lives, the more people will insist that businesses take responsibility for their actions. Doing so requires “response-ability” — the ability to acknowledge people’s concerns and create innovations to address those concerns. It means being open to change and learning. This is not a new challenge, but the importance and complexity of the task have increased with globalization. Thus, tackling the opportunities and dangers that face today’s businesses requires an equally radical shift in the nature of change processes and strategies.

The practice and philosophy of Appreciative Inquiry (AI), while still in its nascent stage, is emerging as a revolutionary approach to this kind of change and learning. AI first arose in the early 1980s, when David Cooperrider, a graduate student at Case Western Reserve University, conducted an organizational diagnosis of the Cleveland Clinic. During his research, he was amazed by the level of cooperation, innovation, and egalitarian governance that he observed within the organization. Cooperrider and his adviser, Suresh Srivastva, analyzed the factors that contributed to the functioning of the clinic when it was at its best — its moments of exceptional performance. In the mid 1980s, they published the first widely distributed description of the research, theory, and practice of Appreciative Inquiry in the article “Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life” in Research in Organization Change and Development, vol. 1, edited by W. Pasmore and R. Woodman (JAI Press, 1987).

WATCH OUT FOR THE ROCK!

AI is based on a deceptively simple premise: that organizations grow in the direction of what they repeatedly ask questions about and focus their attention on. Why make this assumption? Research in sociology has shown that when people study problems and conflicts, the number and severity of the problems they identify actually increase. But when they study human ideals and achievements, peak experiences, and best practices, these things — not the conflicts — tend to flourish. (Did you ever notice that beginner bicyclists tend to steer toward whatever they’re looking at most — like the big rock at the side of the road? See “Watch Out for the Rock!”)

By encouraging people to ask certain kinds of questions, make shared meaning of the answers, and act on the responses, AI serves as a wellspring for transformational change. It supports organizationwide (i.e., systemic) learning through several means:

- Through widespread inquiry, it helps everyone perceive the need for change, explore new possibilities, and contribute to solutions.

- Through customized interview guides, it emphasizes questions that focus on moments of high performance in order to ignite transformative dialogue and action within the organization.

- Through alignment of the organization’s formal and informal structures with its purpose and principles, it translates shared vision into reality and belief into practice.

A Closer Look at Appreciative Inquiry

To see how this process works, imagine what would happen if you shifted the focus of inquiry (i.e., the process of gathering information for the purpose of learning and changing) from the deficits or gaps in your organization to its successes and accomplishments. Instead of asking, “What are our problems? What hasn’t worked?” you might say, “Describe a time when things were really going well around here. What conditions were present at those moments and what organizational changes would allow more of those conditions to prevail?” This simple shift in perspective constitutes a powerful intervention in its own right that can begin nudging the whole company in the direction of the inquiry.

How? Organizations are manifestations of the human imagination. That is, no organization could exist if one or several individuals hadn’t envisioned it first (even if that vision was sketchy or incomplete). The learnings that surface through the AI process begin to shift the collective image that people hold of the organization. In their daily encounters, members start to create together compelling new images of the company’s future. These images immediately initiate small “ripples” in how employees think about the work they do, their relationships, their roles, and so on. Over time, these ripples turn into waves; the more positive questions participants ask, the more they incorporate the learnings they glean from those questions in daily behaviors and, ultimately, in the organization’s infrastructure.

Unlike many behavioral-science approaches to change, AI does not focus on changing people. Instead, it invites people to engage in building the kinds of organizations and communities that they want to live in. AI thus involves collaborative discovery of what makes an organization most effective, in economic, ecological, and human terms. From there, organization members weave that new knowledge into the fabric of the firm’s formal and informal systems, such as the way they develop and implement business strategy or the way they organize themselves to accomplish tasks. This process represents true learning and change.

Finally, AI rests on another deceptively simple notion: that organizational members are competent adults capable of learning from their own experiences and from those of others. In a company that truly believes this precept, everyone feels energized by new knowledge and change. As AI becomes a regular way of working, employees at all levels and all functions identify best practices that the organization can build on in order to respond to new challenges. They then spread that knowledge and initiate action as a matter of routine.

Consultant Diana Whitney has summarized Appreciative Inquiry in the following way:

- AI is a high-participation, full voice process targeted at organizational innovation. People at all levels of an organization engage with one another to discover, dream, and design the corporation’s future.

- AI is an organizational learning process designed to identify and disseminate best practices. AI assumes that people possess high levels of competence and encourages them to discover what works within their own organization as well as in other businesses and organizations.

- AI fosters positive communication and can result in the formation of deep and meaningful relationships. Through simple interpersonal communication, people build relationships, accomplish work, and express value.

- • AI can be used to radically redesign the governance structures and processes of an organization. By applying what they learn from the inquiry, people begin to redesign the organization’s social architecture — its systems, structures, roles, and measures — in ways that better align it with their dreams and needs.

One of the most attractive aspects of AI is its flexibility. Organizations that have implemented AI have found that it engages individuals and teams while it simultaneously provides a framework for companywide innovations.

The Five “D’s”

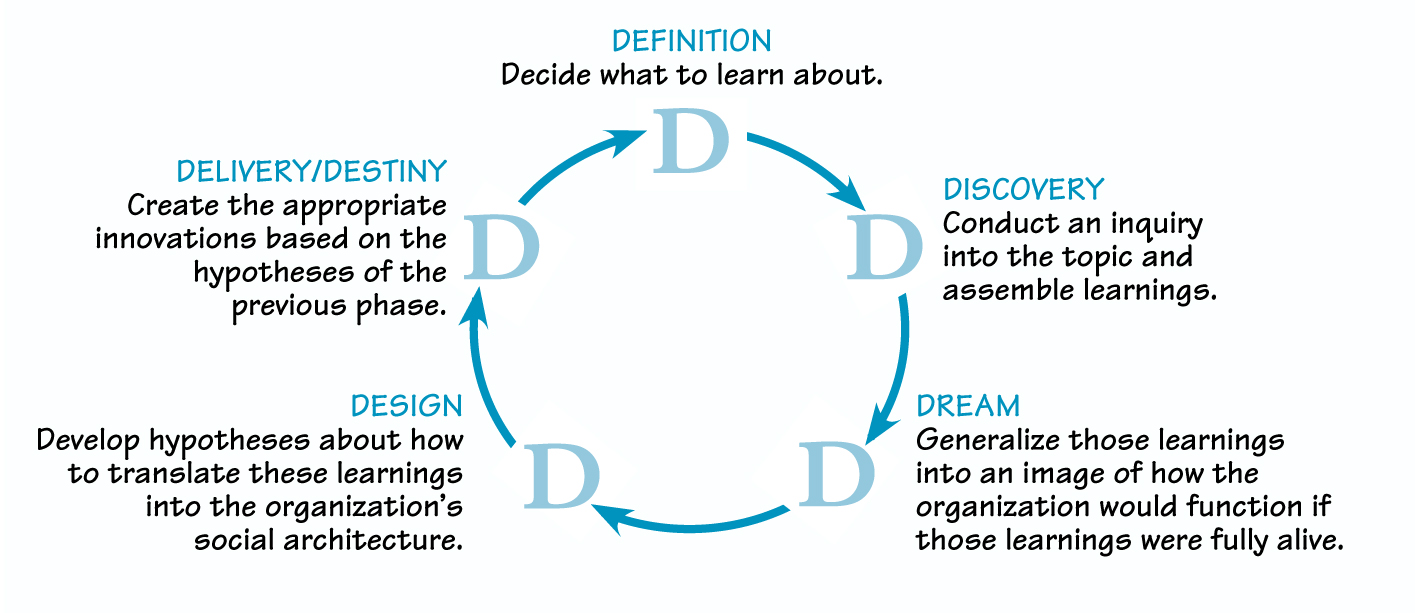

Thus, AI is a way of managing and working as well as a process for organizational learning and change. From the latter perspective, it is an ongoing, iterative cycle consisting of five phases: Definition, Discovery, Dream, Design, and Delivery/Destiny (see “The Five ‘D’s’ of Appreciative Inquiry” on p. 1). In large companies, the process often begins by engaging individual units or divisions. In small companies, everyone can take part right from the start.

Definition. This phase is arguably the most important one in the AI cycle, because it establishes the initial focus and scope of the inquiry. Defining the direction of inquiry is much more than just sharpening a problem description. Because organizations move in the direction of the questions they ask, the choice of questions is vital.

In the Definition phase, the organization’s focus shifts from describing the problem to determining what its members want to achieve and what they need to know to get there. For example, when a Mexican cosmetics firm wanted to solve the problem of discrimination against women, the management team first asked consultants to help them understand the causes of this unequal treatment. Dissatisfied with the direction their conversations were taking, they decided to shift their focus — to inquire instead into the causes and conditions that contribute to excellent cross-gender relationships in the workplace.

This change led the organization to a whole new body of knowledge about the issue. The members of the firm then came up with a compelling vision that they could work toward based on the conversations that took place during the inquiry process: a business world in which everyone is treated fairly regardless of gender. Not long thereafter, the company won an award for having one of Mexico’s most supportive workplaces for women.

Discovery. In the Discovery phase, participants interview hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people from within and outside of the organization. Interviewers use a customized guide to gather information on the line of inquiry that the group identified during the Definition phase. Frequently, a small group of volunteers develops the guide. These volunteers often represent a diagonal “slice” of the organization, along with representatives from key partners outside the company’s formal boundaries (i.e., customers and suppliers). Sometimes this volunteer group conducts the interviews; other times, hundreds of people gather to interview each other. During the Discovery phase, the organization identifies “best practices,” “life-giving forces,” or “root causes of success.”

This practice represents a dramatic departure from normal statistical “sampling.” AI operates on the premise that the act of asking positive questions is as important as the data it elicits. For that reason, the more people interviewed, the stronger the organization’s movement in the direction of the inquiry.

Dream. Participants then come together to build on the new learnings developed during the Discovery phase. They also ask larger questions, such as “What is the world calling us to become? What are those things about us that, no matter how much we change, we want to continue to do in the future?” Dream meetings can range from small teams to “summits” in which hundreds of people participate.

During this phase, people throughout the business create images of what life in the organization and its relationships with key constituents would look like if the company’s very best practices became the norm rather than the exception. This approach differs greatly from other visioning processes, because these dreams are grounded in what participants know to be the system’s past or present capabilities. For example, the employees of a transnational pharmaceutical company developed the following dream:

“The Research Organization of ABC Pharmaceuticals has four significant assets: an energizing work environment that affords freedom of action at all levels; a research process that is market-focused, goal-oriented, and strategically driven; world-class science supported by state-of-the-art technologies; and multi-disciplinary collaboration that transcends internal and external boundaries.

“Our people like to work here. The work environment is creative and empowering. . . . Our collaborative culture leads to sharing across functions. . . . People leverage and learn from each other’s expertise to jointly reach our organization’s goals. ABC Pharmaceuticals is a scientific Center of Excellence!”

Design. During the Design phase, participants identify the high-leverage changes in the organization’s systems, processes, roles, measures, and structures necessary for achieving the dream. Participants craft micro-images, or design statements, for redesigning the corporation’s infrastructure. For example, a consumer products distribution company wrote the following micro-image (one of about 20) describing its ideal strategy development process:

“DIA accelerates its learning through an annual strategic planning conference that involves all 500 people in the firm as well as key partners and stakeholders. As a setting for strategic learning, teams present their benchmarking studies of the best five other organizations, deemed leaders in their class. Other teams present an annual appreciative analysis of DIA, and together these databases of success stories (internal and external) help set the stage for DIA’s strategic, future search planning” (from “A Positive Revolution in Change: Appreciative Inquiry,” by David Cooperrider and Diana Whitney in Appreciative Inquiry: Rethinking Human and Organizational Change, by Cooperrider, et al. (Stipes Publishing, 2000)).

The Design phase is more than just breaking down the dream into short-term actions; it is about “translating” the dream into the “language” of the organization’s social architecture. It is about enacting the essence of the vision in the policies, core processes and practices, and systems — all of the formal and informal structures that sustain the corporation’s essence.

Delivery/Destiny. In the Delivery/Destiny phase, the organization fleshes out, experiments with, and redesigns yet again the innovations that it identified during the Design phase. The hallmarks of this phase are creativity, innovation, and iteration — buttressed by ongoing inquiries into the progress being made and the effectiveness of the changes. Employees work to identify, highlight, and expand what is working well. They also continue to innovate where needed, so that the organization can grow and learn.

The main challenge that groups face during this stage is sustaining — and even magnifying — the inspiration that characterizes the earlier phases. We come from a “project mentality” that values clear starts and conclusions. But we are increasingly confronted with a world in which change does not occur during a separate time period, after which we get back to business as usual. Rather, change is now the very water in which we swim.

We are increasingly confronted with a world in which change does not occur during a separate time period, after which we get back to business as usual. Rather, change is now the very water in which we swim.

First Steps Toward Appreciative Inquiry

There’s no one right way to engage in Appreciative Inquiry; indeed, the process can take many different forms. The examples in the following section illustrate just a few of the many different ways that organizations have applied Appreciative Inquiry — with variations on the topic of inquiry, the process for discovering exceptional moments, the method used in dreaming new futures, and the innovations developed in the Design and Delivery/Destiny phases. But the following conditions seem to be present when Appreciative Inquiry has been most effectively incorporated into a process of organizational learning and change:

- The organization honestly acknowledges any difficulties that currently exist. After all, this kind of struggle often provides the impetus for change. AI practitioners don’t advocate denying negative emotions or problems. Rather, they encourage participants not to dwell on them.

- The organization’s formal and informal leaders have expressed a need or desire for deep inquiry, discovery, and renewal. They’ve also demonstrated an openness to grassroots innovation.

- The organizational culture supports participation of all voices, at all levels — with the understanding that, when participative processes are used, outcomes cannot be known in advance.

- People throughout the organization see change as an ongoing process, not a one-time event.

- The company’s leaders believe in the organization’s capabilities and agree that accessing this “positive core” can drive learning and change.

- The organization supplies the structures and resources needed to collect “good-news stories” and support creative action (from “Appreciative Inquiry: An Overview” by Kendi Rossi, from the AI List Serv, 1999).

These conditions can expedite the AI process, but they are not prerequisites. Unlike other approaches to intentional change, with AI, you can start anywhere, anytime, and with anyone. Most companies learn AI by doing it. The very act of inquiring into the best moments of an organization’s life begins to shift the system. As this process continues, individuals become open to wider applications of Appreciative Inquiry. They begin with some trepidation and generally end up with a strong commitment to the principles and practice.

AI in Action

AI has been used to catalyze change in a wide range of efforts: from business process excellence, diversity, and knowledge management, to customer service, mergers and acquisitions, and community development. Though it is still in its infancy, proponents of this work have scored some remarkable successes, as the examples below reveal.

In 1999, Nutrimental SA, a food manufacturing facility in Paraná, Brazil, shut down so that all 700 employees could talk together about how to beat the stiffening competition facing the company. The co-CEOs invited David Cooperrider (currently a faculty member at Case Western Reserve University) to facilitate. Cooperrider asked employees to identify “the factors and forces that gave life to the company when it was most effective, most alive, and most successful as a producer of high-quality health foods.” In an interview, Cooperrider described what happened:

“With cheers and good wishes, a smaller group of 150 stakeholders — employees from all levels, suppliers, distributors, community leaders, financiers, and customers — launched a four-day strategy session during which they articulated a new and bold corporate dream. Participants said, ‘Let’s assume that tomorrow, when we wake up, a miracle will have occurred: We’ll discover that all of Nutrimental’s best qualities have come to the fore in exactly the way we would like. What would we see when we arrived at work that would tell us that this miracle had happened? What would be different?’ Over the following days, participants clarified three new, strategic business directions.

“Six months later, Nutrimental’s profits had increased by a whopping 300 percent. The co-CEOs attributed these dramatic results to two changes: bringing the whole organization into the planning process, and realizing that organizations thrive when people see the best in one another, when they can affirm their dreams and ultimate concerns, and when their voices are heard.”

At about the same time, in Harlow, England, members of an internal organization-development (OD) group at a transnational pharmaceutical company and their clients decided to use AI in evaluating an intervention. The goal of the initiative had been to improve core business processes and, ultimately, the quality of life for their research scientists. The OD practitioners and representatives from the research community fanned out to ask questions of both the scientists who had participated in the intervention and their supervisors.

But rather than asking whether the intervention worked, they asked how it had helped people to work together more effectively and in what ways the quality of their work lives had been enhanced. As a result, the evaluators compiled a rich collection of data, in the form of stories, themes, and recommendations, that promises to yield even more powerful interventions in the future.

In a primary school in Maine, Tom Morrill, the new principal, faced a faculty struggling with the impact of a recent merging of three schools into one. After a few brief meetings with a consultant, the school’s leadership team decided to engage the faculty and staff in three two-hour meetings. During the meetings, participants identified the best aspects of the cultures they had left behind and explored ways to carry those elements forward into a shared future. Morrill described the outcome of this approach:

“People’s interactions focused on what was working well or on kernels of possibilities, as opposed to lists of what was wrong. Now, you hear teachers talking about AI frequently. We have also used AI in decision-making. I’ve purposefully moved to a more inclusive decision-making model, which reflects people’s desire for inclusion. Also, team leaders have used AI to create reporting processes and even staffing arrangements. This has built better school unity and has strengthened communication. People are getting better about working and planning together.”

NEXT STEPS

- The next time someone in your team says, “Let’s critique our meeting,” ask if she would be willing to have each person describe what he or she considers the best part of the meeting and offer suggestions for how participants can do more of that in future gatherings.

- The next time you have a few minutes with your significant other, say: “You know, I’m curious about what you think of as the really good times in our relationship. Would you tell me about one event that stands out for you as a highlight?”

- The next time you have an opportunity to evaluate someone’s performance, consider asking him to tell you about the times when he felt most competent and effective. Then ask him what he thinks you and he could do to increase the frequency of those times in the future.

Appreciative Inquiry as an approach to intentional change is still evolving. We are all in the process of learning how to use this radically different, yet breathtakingly simple approach in ways that truly energize and sustain learning organizations. But we do know that AI is best learned by doing.

In Leading the Revolution, Gary Hamel said: “The world is increasingly divided into two kinds of organizations: those that can get no further than continuous improvement, and those who’ve made the jump to radical innovation.” Companies that see the need for the latter approach to change are increasingly turning to Appreciative Inquiry as a tool for making this leap. We invite you to do the same.

Bernard Mohr (bjmSynapse@aol.com) is the founder of The Synapse Group, Inc., an international consultancy in the fields of organizational learning, design, and capability building. His focus is the collaborative innovation of new work settings that are ecologically sound and economically sustainable, and that bring out the best in human beings. He is a founding partner of Appreciative Inquiry Consulting and co-author of the forthcoming book, Appreciative Inquiry: Change at the Speed of Imagination (Jossey Bass, 2001).

Author’s Note: Many of the concepts in this article have evolved from ongoing dialogues, both verbal and written, with my colleagues in the Appreciative Inquiry Consulting founders’ group: Jim Ludema, Diana Whitney, Adrian McLean, Marsha George, Jane Watkins, David Cooperrider, Marge Schiller, Diane Robbins, Steve Cato, Frank Barrett, Joep de Jong, Mette Jacobsgaard, Jim Lord, Ada Jo Mann, Anne Radford, Judy Rodgers, Jackie Kelm, David Chandler, Ralph Kelly, and Barbara Sloan.